What`s for Lunch? - The Young Scientist Program

advertisement

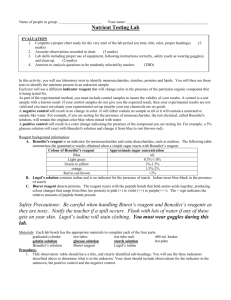

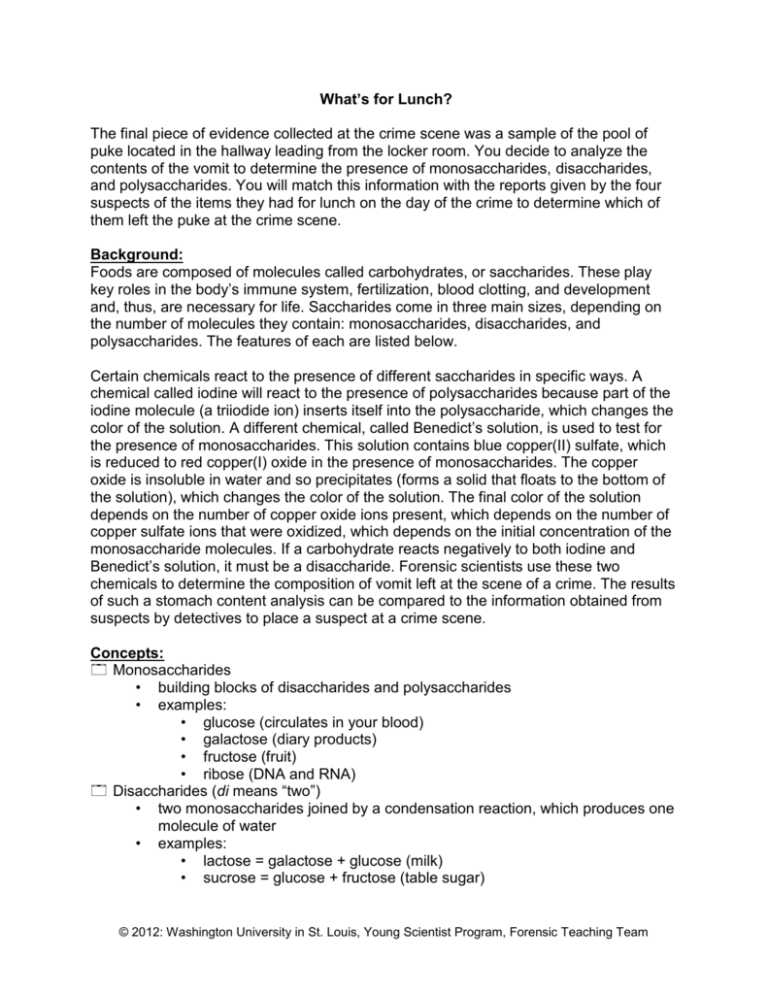

What’s for Lunch? The final piece of evidence collected at the crime scene was a sample of the pool of puke located in the hallway leading from the locker room. You decide to analyze the contents of the vomit to determine the presence of monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides. You will match this information with the reports given by the four suspects of the items they had for lunch on the day of the crime to determine which of them left the puke at the crime scene. Background: Foods are composed of molecules called carbohydrates, or saccharides. These play key roles in the body’s immune system, fertilization, blood clotting, and development and, thus, are necessary for life. Saccharides come in three main sizes, depending on the number of molecules they contain: monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides. The features of each are listed below. Certain chemicals react to the presence of different saccharides in specific ways. A chemical called iodine will react to the presence of polysaccharides because part of the iodine molecule (a triiodide ion) inserts itself into the polysaccharide, which changes the color of the solution. A different chemical, called Benedict’s solution, is used to test for the presence of monosaccharides. This solution contains blue copper(II) sulfate, which is reduced to red copper(I) oxide in the presence of monosaccharides. The copper oxide is insoluble in water and so precipitates (forms a solid that floats to the bottom of the solution), which changes the color of the solution. The final color of the solution depends on the number of copper oxide ions present, which depends on the number of copper sulfate ions that were oxidized, which depends on the initial concentration of the monosaccharide molecules. If a carbohydrate reacts negatively to both iodine and Benedict’s solution, it must be a disaccharide. Forensic scientists use these two chemicals to determine the composition of vomit left at the scene of a crime. The results of such a stomach content analysis can be compared to the information obtained from suspects by detectives to place a suspect at a crime scene. Concepts: Monosaccharides • building blocks of disaccharides and polysaccharides • examples: • glucose (circulates in your blood) • galactose (diary products) • fructose (fruit) • ribose (DNA and RNA) Disaccharides (di means “two”) • two monosaccharides joined by a condensation reaction, which produces one molecule of water • examples: • lactose = galactose + glucose (milk) • sucrose = glucose + fructose (table sugar) © 2012: Washington University in St. Louis, Young Scientist Program, Forensic Teaching Team Polysaccharides (poly means “many”) • multiple monosaccharides joined together • serve as energy storage units and structural components • examples: • starch (potatoes, rice, wheat, maize) • glycogen (glucose polymer in animals) • cellulose (glucose polymer in plants, wood, paper, cotton) • chitin (glucose polymer in fungi and insects) Detective’s Report: • Suspect 1: spinach salad, bottled water • Suspect 2: package of strawberries, bottle of 2% milk • Suspect 3: bowl of spaghetti, coke zero • Suspect 4: peanut butter and jelly sandwich, bottle of 2% milk, package of cookies Materials: • • • • • • • • • Benedict’s solution iodine low concentration monosaccharide medium concentration monosaccharide high concentration monosaccharide disaccharide polysaccharide hot plate beaker with water © 2012: Washington University in St. Louis, Young Scientist Program, Forensic Teaching Team Procedure: Part 1: Monosaccharide Controls 1. Label 6 tubes: a. water b. low mono c. medium mono d. high mono e. di f. poly 2. Add 20 drops of respective solution to each tube. 3. Add 10 drops of Benedict’s solution to each tube. 4. Place tubes in hot water bath for 2-3 minutes. 5. Remove test tubes and record any color changes. Test Tube Beginning Color Ending Color Monosaccharides (Y/N)? water low mono medium mono high mono di poly 6. Analysis: a. What color does Benedict’s solution turn in the presence of a monosaccharide? b. Give three examples of foods that contain monosaccharides and give the specific monosaccharide found in these foods. © 2012: Washington University in St. Louis, Young Scientist Program, Forensic Teaching Team Part 2: Polysaccharide Controls 1. Label 6 tubes: a. water b. low mono c. medium mono d. high mono e. di f. poly 2. Add 20 drops of respective solution to each tube. 3. Add 10 drops of iodine solution to each tube. 4. Record any color changes. Test Tube Beginning Color Ending Color Polysaccharides (Y/N)? water low mono medium mono high mono di poly 5. Analysis: a. What color does iodine turn in the presence of a polysaccharide? b. Name five foods that contain polysaccharides. Part 3: Stomach Content Analysis 1. Label 2 tubes: a. Benedict’s © 2012: Washington University in St. Louis, Young Scientist Program, Forensic Teaching Team b. Iodine 2. Add 20 drops of the crime scene sample to each tube. 3. Add 10 drops of Benedict’s solution to the correctly labeled tube. 4. Place Benedict’s tube in hot water bath for 2-3 minutes. 5. Record any color change. 6. Add 10 drops of iodine to the other labeled tube. 7. Record any color change. Test Tube Monosaccharides (Y/N)? Low, Medium, or High Monosaccharides? Polysaccharides (Y/N)? Benedict’s Iodine Response Questions: 1. Based on the detective’s report, list which saccharides were consumed by each suspect for lunch. 2. Based on the results of your stomach content analysis, what is the composition of the crime scene vomit? 3. Based on your answers to questions 1 and 2, which suspect left the vomit at the crime scene? 4. Why might these results be insufficient to convict someone in a court of law? © 2012: Washington University in St. Louis, Young Scientist Program, Forensic Teaching Team