character telling, showing, techniques and dialogue.doc

advertisement

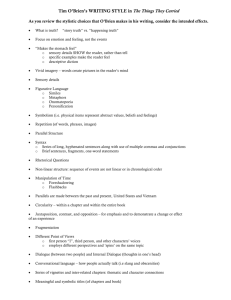

Narrative Devices

Character – Two approaches

Another important ingredient of a good story is the characters. The characters need to be

realistic and believable; otherwise they won’t hold our interest.

Presenting characters by telling

A direct way of presenting a character is by telling. The advantage of this style is that it is quick

and straightforward. It leaves little room for the listener or reader to misunderstand you.

Some key points to consider when creating or writing about a character:

What the character looks like

What the character says and thinks

How the character behaves

What other characters say or think about them.

Read the description below. What do you learn about the character of Mr Fletcher from this

description?

Mr Fletcher taught us Latin. He was the shape of a domino. No, that's wrong, because he wasn't square; he

looked as if he had been cut out of a domino. He had shape but no depth, you felt he could have slipped

through the crack at the hinge of a door if he'd gone sideways. Though I daresay if he'd really been able to

do that he would have made more use of the faculty1; he was great on stealing quietly along a passage and

then opening the door very fast to see what we were all up to; he used to drift about silently like an old

ghost, but if you had a keen sense of smell you always had advance warning of his arrival because of the

capsule of stale cigarette smoke that he moved about in. He smoked nonstop; he used a holder, but even so his

fingers were yellow up to the knuckles and so were his teeth when he bared them in a horse-grin. He had

dusty black hair that hung in a lank2 flop over his big square forehead, and his feet were enormous; they

curved as he put them down like a duck's flippers, which, I suppose, was why he could move so quietly ... If

someone kicked up a disturbance at the back of the classroom he'd first screw up his eyes and stick his head

out, so that he looked like a snake, weaving his head about to try and focus on the guy who was making the

row; then he'd start slowly down the aisle, thrusting his face between each line of desks; I can tell you it was

quite an unnerving performance ...

None of our lot cared greatly for Latin, we didn't see the point of it, so we didn't have much in common with

old Fletcher. We thought he was a funny old coot, a total square - he used words like "topping' and 'ripping'

which he must have picked out of the Boy's Own Paper in the nineteen-tens. He was dead keen on his subject

and would have taught it quite well if anyone had been interested; the only time you saw a wintry smile light

up his yellow face was when he was pointing out the beauties of some construction3 in Livy4 or Horace5.

From Dead Language Master by Joan Aiken

1

ability

Long and limp

3

Sentence construction

4

and

5

Latin authors

2

1

2

Over to you

Now it's your turn to write a short description of a character. Choose someone

you know, such as a friend, parent or teacher. Write about him or her as a character

in a story. Imagine that the character is being introduced at the start of a chapter.

Present him or her in a situation and tell the reader about his / her:

Appearance (clothes, height, build, body

language, stance, gestures)

Mannerisms or habits

Thoughts (about her / himself, about

what has just happened, about the

future, about other people)

Hopes (in the near future, in the longer

term)

Before writing your description, brainstorm your ideas using a mental mapping diagram like the

one below.

Character

mannerisms

appearance : short,

powerfully built

Remember to read your work through carefully, correcting any errors and redrafting sentences that

could be improved. Make certain you've linked your sentences in an interesting way. Get rid of any

excess use of 'and' and 'then'. Finish with a brief comment summing up how well you think you

have completed the task.

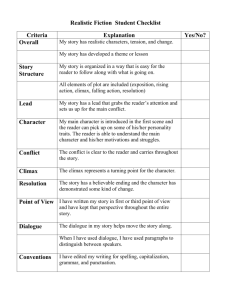

Swap your character portrait with a partner's. Go through the checklist (below) to see how many

ways your partner has used to bring his or her character to life. Can you suggest any ways of

improving the description?

• Are we told what the character looks like?

• Are we told what the character says or thinks?

• Are we told how the character behaves?

• Are we told what other people say or think about the character?

What are the disadvantages of this method of presenting a character?

3

Presenting characters by showing

If 'telling' is the most direct way of giving the reader information about a

character, 'showing' can make the reader feel more actively involved in a story.

Telling is when the writer gives us statements about what a character thinks or

feels. Showing is when the writer describes the character's actions, leaving us

to work out what s/he is thinking or feeling. For example:

Telling

As he cleared his desk, Peter was in a furious temper.

Showing

Peter cleared his desk, snatching at heaps of paper and hurling them into the bin.

Notice:

• with telling the reader knows exactly what Peter is feeling

• with showing we see how he behaves, but the writer leaves us to do more of the work. Clues like

'snatching' and 'hurling' suggest aggression and anger. From this we infer that Peter is in a furious

temper.

Getting started

The secret of showing your reader what a character is like lies in choosing your vocabulary

carefully. One word can be a vital clue to what a character is thinking or feeling.

Look at these examples and try to work out what clues the writer might be giving us about the

character's thoughts, feelings, personality, or appearance. The first example is done for you.

Extract

The man shuffled towards the run-down

house.

Character point

The man is old or infirm.

Main clue

'Shuffled' suggests he cannot

walk well -because he is either

old or ill.

Rita sat on the bottom step and placed

her head in her hands.

He sat outside the room and again

touched his collar, then his tie.

Kay moved quickly from the armchair to

her desk. There she began writing

frantically.

As he listened to the student's story, Mr

Parker's hands tightened.

Writing practice

Notice how simply you can show a reader about a character:

Andy yawned. 'You'll be lucky,' he said.

Character message: suggests boredom - lack of belief in the person he's talking to.

Andy lowered his voice. 'You'll be lucky,' he whispered.

4

Character message: suggests secrecy, perhaps menace, or that they are being overheard.

Write five more sentences about Andy, changing the two highlighted elements in each sentence,

and then saying what the character message might be. To get you started, try to show Andy as

sarcastic and then really happy.

The importance of detail

Small details of description can be a really good way of telling your reader

about your characters.

E.g. Laura sat in her car.

What do we know about Laura? We know what she is doing but little else.

Carefully-judged description can give the reader vital clues:

E. g. Laura sat in her Porsche.

Now we begin to make judgements about Laura’s background, her lifestyle and her wealth.

What about:

Laura shifted uneasily in her Porsche. She looked in the rear view mirror and lowered her

heard suddenly as if she were reading a book or magazine.

What do we learn about her attitude or feelings?

Her lifestyle?

Her behaviour?

You can use all kinds of description to illuminate character:

Appearance

Bystanders

• Laura's sunglasses hid her concern.

Bystanders are other characters. You can use

• Her mouth turned down at the edges.

them to give information about your main

character, or to show her from a different

viewpoint:

• The man cleaning the window of the shop

watched her light a cigarette.

• Bart Van Ingen, walking to work, noticed a

woman in sunglasses in a smart car and thought

no more about it.

Setting

Hints

• The traffic roared past as she sat there

• Keep your details brief and precise - not great

[showing that she's isolated].

slabs of description.

• The sky darkened [suggesting danger].

• Keep description visual - appearances,

textures, colours, movements - to help your

reader see the scene

• Give specific details, e.g. 'a Porsche', 'a Jeep',

rather than 'a car'. Details like these can tell us

about a character. ('He ate his half-melted

Balisto’ is more interesting than 'He ate his

chocolate bar'.)

Actions

• She tapped her fingers rapidly on the

dashboard [suggesting nervousness].

• She fumbled beneath the seat for her briefcase

['fumbled' suggests that she's in a rush].

Writing practice

5

Practise using some of these techniques with the writing task below. Aim to produce a really lively,

interesting piece of writing that would work well within a story. Use descriptions of people and

places, plus dialogue if you wish, to bring the scene alive.

Imagine a character waiting in a queue at a bank. He is in a terrible hurry to get money out, in

order to go across the street to buy a phone. It is the last day of the sale and it is now 5.20. He has

ten minutes to get the money, cross the street and buy the phone. Call him Rob Dawson. Make up

any other details.

Descriptive Techniques:

Look at the following description of a tramp. Find the similes and metaphors and underline them:

The old tramp sits on a park bench. His eyes are misty goldfish bowls. His fingers are

frail brown twigs that will snap if he releases his brown paper bag. His hair is matted

straw and his skin is crumpled, dirty parchment, rough sandpaper holding his face

together. His clothes are but rags, and hang off him like the loose sails of a lost ship.

As he sits there he shivers. He is a puppy thrown out in the cold, a broken toy, a lost

child amongst strangers. An unwanted, tired, lonely old man….

Explore the metaphors used in this description by drawing up Venn diagrams, like this:

Use the third circle to explore the comparison. How has the writer decided that ‘eyes’ and ‘misty

goldfish bowls’ are similar?

6

Now go back through the description and highlight the different sentence types you find in

different colours. What do you notice?

Controlling Sentences to convey meaning

Look at this sentence:

The boy watched.

Why does this sentence lack impact and interest for the reader?

Make changes to the sentence using the following techniques:

Add information to the noun, e.g. silent, menacing, loyal, gleeful.

Strengthen the noun by using a proper noun, e.g. William.

Add to the verb in any way you choose, e.g. watched and waited; watched but failed to see

what was in front of him.

Add a simile to the sentence, e.g. like a shadow the boy watched, then faded into the

darkness.

Trim the simile to remove the word ‘like’ and adjust the sentence accordingly, e.g. A

shadow in the darkness, the boy watched and waited.

Now repeat this process with the following sentence:

The creature spoke.

Getting the amount of description right

Different readers probably like different levels of description. In general, though, it seems that

modern readers prefer the story to keep moving, rather than encounter big slabs of description.

One of the big dangers for new writers is that they tell the reader too much at once about people

and places. With characters, this can really get in the way of the action, slowing the story down and

leading to a loss of tension.

Here's how to get the balance right.

When you know your character well, you can be tempted to try to tell your reader everything about

her or him. This can really slow the pace of the story down, like this:

Tom looked up and saw Mel, from his class, in the doorway. She was tall with fair

hair. Today she was wearing grey jeans and a blue top. She was a friendly cheerful

girl and her sense of humour meant she had lots of friends. She lived in a big house

on Carter Street with her mum, who was a dentist, and her two brothers and her

dog, Tip. 'Hi,’ said Tom.

7

Notice:

• how much telling is going on here: the writer tells us what Mel looks like, where she lives, who

she lives with, even what her mother's job is

• how this amount of description slows the whole story down by getting in the way.

You could cut all the description, like this:

Tom looked up and saw Mel. 'Hi,' he said.

Notice that we lose all the visual detail of where the story takes place and who the characters are.

We need more detail than this.

Alternatively, you could cut between description and action to create a more balanced effect, like

this:

Tom looked up and saw Mel, from his class, in the doorway.

'Hi,' he said.

'Hi. How are you?' she asked, and flicked her long fair hair our of her eyes.

She was smiling. She was always smiling; Tom supposed that was one reason she was

so popular.

Tom shrugged his shoulders. 'Okay, I suppose.'

Mel dug her hands into the pockets of her grey jeans. She looked at him.

'Something the matter?'

'It's okay,' said Tom, and he started to walk away.

‘Tom, come on. There's obviously something wrong. Look, I can tell. You're behaving

just like Alec when he's bothered about something.' Alec was Mel's brother, a year

older than both her and Tom.

Notice:

• the cutting between description, dialogue and action

• how this creates pace and tension

• how the writer is still able to give details about Mel - but not all in one slab of description.

Dialogue

The final element to consider before you write your own

short story is how to make your characters come alive

through dialogue.

Read the following dialogue from the opening of a novel

called Goodnight Mr Tom by Michelle Magorian.

It is 1939 and city children are being moved out to the country, away from the dangers of bombs. It

is the job of volunteers called billeting officers to place the children in homes. In this case, a

middle-aged female billeting officer has called round to see a man called Thomas Oakley. Thomas

Oakley speaks first:

8

Goodnight Mr Tom

'Yes. What d'you want?'

'I'm the Billeting Officer for this area.'

'Oh yes, and what's that got to do wi' me?'

'Well, Mr, Mr ...’

'Oakley. Thomas Oakley.'

'Ah, thank you, Mr Oakley. Mr Oakley, with the declaration of war imminent

...'

'I knows all that. Git to the point. What d'you want?' (He noticed a small boy at

her side.)

'It's him I've come about, I'm on my way to your village hall with the others.'

'What others?'

From Goodnight Mr Tom by Michelle Magorian

The writer uses dialogue to create the characters of Tom and the Billeting Officer and to make the

difference between them clear,

1. Tom is given an interesting way of talking. He shortens words and says words in a way that

may be considered to be different from usual, 'standard' English. Write down examples of these.

2. Compare how Tom speaks with the way the Billeting Officer speaks. How would you

sum up the differences between the two?

In your own story writing you should use similar methods of writing dialogue to make characters

different, and interesting. It is quite easy to capture accents and different ways of pronouncing

words.

In the novel there is more than just the dialogue. As you read the full version, reflect on what detail

is added about these two characters. Is the writing better with the description or without it? Does it

make the dialogue easier to follow?

Goodnight Mr Tom

'Yes,' said Tom bluntly, on opening the front door. 'What d'you want?'

A harassed middle-aged woman in a green coat and felt hat stood on his step. He glanced

at the armband on her sleeve. She gave him an awkward smile.

'I'm the Billeting Officer for this area,' she began.

'Oh yes, and what's that got to do wi' me?'

She flushed slightly. 'Well, Mr, Mr ....'

'Oakley. Thomas Oakley.'

'Ah, thank you, Mr Oakley.' She paused and took a deep breath. 'Mr Oakley, with the

declaration of war imminent...'

Tom waved his hand. 'I knows all that. Git to the point. What d'you want?' He noticed a

small boy at her side.

'It's him I've come about,' she said. 'I'm on my way to your village hall with the others.'

'What others?'

She stepped to one side.

From Goodnight Mr Tom by Michelle Magorian

How do the words in bold in the table below:

1. help the reader to hear more clearly how the two characters speak?

2. reveal what the characters are like?

9

Tom

'Yes,’ said Tom bluntly.

Tom waved his hand.

The Billeting Officer

She flushed slightly.

'She paused and took a deep breath.'

Layout and punctuation are very important when putting speech in a story.

1. Investigate the extract with a partner. Find and list the rules which control how speech is set

out. Think about:

*

how words that are spoken are separated from the rest of the story

*

how it is shown that a new person is speaking

*

where speech marks are used

*

where the punctuation goes when closing speech marks

*

where a capital letter is used.

2. When you are writing your own dialogue, avoid using 'he said/she said' all the time. Look up

the word 'say' or 'said' in a thesaurus and see how many words (synonyms) there are to choose

from. Make your own word bank and refer to it when writing stories.

3.

a

b

c

d

e

Rewrite these sentences, changing the word 'said' in each case:

'Fire!' he said.

'Stop tickling me!’ he said.

'I hate you!’ she said.

'If you hate the referee clap your hands,’ they said.

'Oh no, not again!’ she said.

Sometimes using the word 'said' is enough:

'I'd love a puppy,' she said.

But on other occasions you may wish to add detail:

'I'd love a puppy,' she said, gazing longingly in the pet shop window.

Notice that the comma after 'said’ is used to separate the descriptive detail from the details of

speech. The description helps you understand how the girl spoke.

Four tips for writing effective dialogue:

1. Put in enough direct speech to let the reader picture the characters but not so much as to be

boring.

2. For variety, direct speech can be mixed with indirect speech.

3. Good writers use dialogue to reveal more about a character. They don't tell us directly what they

think about a character, but they let the character reveal it indirectly through his or her words.

4. In order for dialogue to be realistic and believable, it needs to reflect the way people actually

speak. This often involves using informal language in which the rules of Standard English are

relaxed. Realistic dialogue may also reflect the dialects in which many people speak.

The Poison Ladies

Follow carefully the first section of 'The Poison Ladies' by H. E. Bates (below). While you are

listening to the story, think about the answers to these questions:

1. What features help to make this dialogue realistic and believable?

10

2. How do you know that the narrator hero-worshipped Ben? (Which lines would you quote as

evidence for this?) Why is this more powerful than being told that the narrator worshipped Ben

when he was a boy?

3. Why does Ben say 'Akky Duck'? Is this effective?

4. What do you think is going to happen?

When you are only four, seven is a hundred and five inches are a mile.

Ben seven and I was four and there were five inches between us. Ben also had big brown leather patches on the seat of

his moley and dark hairs on his legs and a horn-handled knife with two blades, a corkscrew and a thing he called a stabber.

‘Arter we get through the fence,' Ben said, 'we skive round the sloe bushes and under them ash trees and then we're in

the lane and arter that there’s millions and millions o' poison berries. Don't you eat no poison berries, will you? Else you'll die. I

swallered a lot o' poison berries once and I was dead all one night arterwards.'

‘Real dead?’

‘Real dead,’ Ben said. 'All one night.'

‘What does it feel like to be dead?'

‘Fust you git terrible belly ache,' Ben said, 'and then your head keeps going jimmity-jimmity-jimmity-bonk-bonk-bonkclang-bang-jimmity-all the time.'

‘I don’t want to be dead,' 1 said, 'I don't want to be dead.'

‘Then don’t eat no poison berries.'

My blood felt cold.

‘Why don’t we start?' I said. I knew we had a long way to go; Ben said so.

Ben got his knife out and opened the stabber.

‘I got to see if there's any spies fust,' Ben said. 'You stop here.'

‘How long?’

‘Till I git back,’ Ben said, 'Don't you move and don't you shout and don’t you show yourself and don't you eat no

poison berries.'

'No,' I said. ‘No.’

Ben flashed the knife so that the stabber pierced the blackberry shade.

‘You know Ossy Turner?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Yes.'

Ossy had a hare-lip and walked with one drawling foot and a crooked hand. I always felt awfully sorry for Ossy but Ben

said:

'Ossy's like that because he come down here and dint look for spies fust - so they got him and done that to him.'

'Who did?'

Ben was crawling away on hairy knees, flashing the stabber in the sunlight, leaving me alone.

‘The Poison Ladies,' Ben said, 'what live down here. In that house I told you about. The two old wimmin what we're

going to see if we can see.'

It was fifty years before Ben came back. I knew quite well it was fifty years; I counted every one of them.

'No footmarks,' Ben said.

‘I didn't eat any poison berries. I didn't-'

'Let's have a look al your tongue!'

My tongue shot out like a frightened lizard. With big white eyes Ben glared down my throal and said:

'All right. We're going now. Hold your breath.'

'How far is it now?'

'Miles,' Ben said. 'Down the lane and past the shippen and over the brook and then up the lane and across the Akky

Duck.'

I didn't know what the Akky Duck was; I thought it must be a bird.

'It's like bridges,' Ben said. 'It's dark underneath. It's where the water goes over.'

'Do the poison ladies live there?'

'They come jist arterwards,' Ben said. 'We hide under the Akky Duck and arter that you can see 'em squintin' through

the winders.'

The veins about my heart tied themselves in knots as I followed Ben out of the blackberry shade, over the fence, into

the lane and past black bushes of sloe1 powderily bloomed with blue fruit in the sun.

1 a small blue-black fruit

11

5. Has H. E. Bates followed the 'Four tips for writing effective dialogue' in 'The Poison

Ladies'? Find one example of each tip, and share these in a class discussion.

Vocabulary bank:

dialect

dialogue

direct

speech

indirect

speech (also

known as

reported

speech)

informal

language

Standard

English

a variety of English, often based on region, which has distinctive grammar and

vocabulary

a conversation between two people, which may be spoken or written

a way of writing down speech which uses the actual words spoken, e.g. '"I'm

tired," said Dave.'

a way of writing down speech where the words are referred to indirectly, e.g.

'Dave said he was tired.'

language that includes colloquial language, slang and the use of contracted forms

of words, e.g. 'Don't you eat no poison berries.'

the type of spoken and written English that should be used when formal English is

appropriate, e.g. all the explanations and instructions on this page.

12