Unlocking Doors Project Report

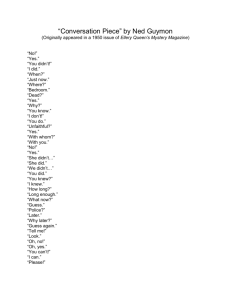

advertisement