THE PERFECTION OF ASKING:

advertisement

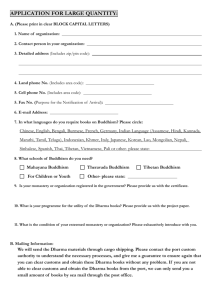

THE PERFECTION OF ASKING: FUND RAISING IN THE FPMT WHAT IT IS AND HOW TO DO IT CPMT 95, ISTITUTO LAMA TSONG KHAPA POMAIA, ITALY “If I give, what shall I eat? If I eat, what shall I give?” TWO ATTITUDES MENTIONED BY SHANTIDEVA INTRODUCTION This organization – the FPMT – what is it for? Our great teacher, Lama Zopa Rinpoche, say we are here to offer ultimate happiness, the greatest possible benefit, to all sentient beings: liberation and enlightenment. We do this by providing the conditions necessary for Dharma to be taught and spread. Our work – that of centre directors and the rest of us – is to create the conditions for teachers t o teach and students to practice. To do this, we need all kinds of help. Thus, when we ask for help with this motivation – the enlightenment of all sentient beings – we are not only generating bodhichitta, the seed of enlightenment, within our own minds, but we are also bringing all sentient beings closer to that ultimate goal. Getting others to help, to create merit, is the action of a bodhisattva. What is fund raising? It isn’t merely asking for money. People can help, and want to help in many ways. Of course, we need money, and the principal goal of most fund raisers is to raise as much money as possible in order to meet whatever targets they have set for themselves. However no centre can exist without the help of many human hands, and although many people may not be able to volunteer their time or contribute money, they might be happy to offer goods or services. Therefore, when making contact with a potential benefactor, the centre fund raiser should keep in mind both the needs of the centre and various possibilities the benefactors represent. How do people become benefactors? First, they become aware of the centre’s existence; then they take an interest. Finding something they like, they begin to support the centre by becoming members and volunteering for jobs. Gradually, passive support turns into active commitment, followed by deep involvement. Like us, as other people experience the benefits of the Dharma, they too want to be a part of it. Do you want your centre to get more money? Simply by asking? It’s out there, waiting for you. In the USA, people give far more to religious organisations than to any other group. I suspect it’s the same in many other countries; people really like contributing money to religious causes. All you have to do is go and get it. In these sessions, I hope to show you how. Why is it me doing this? I hope that by the end of it will be obvious, but basically, because I was asked. (A good lesson for all fund raisers). Ven. Massimo and Paula thought that since I was the only full time fund raiser in FPMT, and have been for a few years now, my experience might be relevant. I’ve actually been raising money for one FPM cause or another for more than twenty years – Kopan, Lawudo, Western sangha, Tushita Delhi, Wisdom Publications, Kurukulla Centre, and a few more – but full time only since the end of 1991. It’s been relatively successful, which has certainly surprised me, and since I’ve received some fund raising and other teachings from impeccable sources and have made a few more up, I thought I might have something to share with you. As I said…we’ll see. I’m also in it for the merit. 1 Anyway, many of us have relied for too long on Rinpoche fund raising for us, and it’s time we took at least this aspect of the foundation’s worldly development into our own hands. I do understand that this is an international gathering and that the laws and financial codes vary a great deal from country to country. So too do customs and beliefs. For example, I have heard some Europeans say that fund raising is a crass American thing that would never work in Europe. I don’t believe that; Europe has a long history of giving to charitable causes and the arts. What they may really be objecting to are American techniques of fund raising. I’m sure our sophisticated, refined European FPMT centres can lead the way in developing new methods of inducing benefactors to support them. There’s no doubt that the seeds of generosity lie not too deeply buried in the European mind; where else has Europe’s great wealth come from? Anyway, whether what these people say is true or not, any system that encourages giving and has developed techniques of asking others to do so can’t be all bad. I’ve also been told that at previous CPMT meetings, some presenters have offered material that is relevant only to their own country. So, I’m going to try to keep this as general as possible, but if I quote from my own experience and the words seems irrelevant, you may have to rely on their meaning. I also want to get through this entire document today, so I’m going to keep the pace up. However, if you think it’s worth using, you’re going to have to read it again and again, so today, let’s just to a glance meditation on it. Read it again tonight, to prepare for tomorrow’s session, when we’ll look at some direct mail materials from Dharma and other organisations, and if there’s time, have some discussion. In our third session, we’re going to work in small groups with the aim of each director being able to go back to his or her centre with a fund raising campaign to put into action. Ideally, of course, the centre director cannot be the centre’s fund raiser, but for the sake of these fund raising exercise, visualise that you are your centre’s fund raiser. In that way I think you’ll get more out of these sessions. And if you get any ideas for your centre as we go along, write them down. Now, before going on with the more technical aspects of fund raising, let’s look at a few Buddhist ones. SOME BUDDHIST ASPECTS Motivation I’ve already mentioned the crucial importance of the fund raiser’s having a perfect Mahayana motivation, and the more convinced you are that asking is a highly beneficial Dharma activity, the closer you’ll come to that perfect motivation. If you ever feel bad about asking someone for money – guilty, apologetic – check your motivation. Anyway, you’re the bearer of good tidings; you should feel as though you’re telling prospective benefactors that they have won the lottery. It’s actually better than that. Giving is the first of the six perfections, and asking is definitely giving – you are giving the potential benefactor the chance to create enormous merit. Of course, how much merit depends upon the person’s motivation, but since the money will be used to offer Dharma to all sentient beings, even a person giving with negative motivation probably creates some merit too. However, if over the course of your relationship with benefactors you can lead them in a very skilful way to extend their motivation, you’re doing them an even greater favour than just giving them an opportunity to give. More so if you can explain the benefits of giving. Teaching others to give is leading them on the path. 2 Also in the lam-rim is mention of three kinds of giving – material, fearlessness, and Dharma. Of the three, the giving of Dharma is the highest form, so we are really offering a great opportunity when we ask someone to help the centre bring Dharma to all sentient beings. Dedication When you have received a donation, dedicate the benefactor’s merits and your own in the widest way possible, meditating on the emptiness of all. Karma The last but most important Dharma aspect I want to mention here is karma. If you, the fund raiser, your centre, the FPMT, or whoever else might benefit from a particular donation has not created the cause to it, you won’t get it. Therefore, if we want our efforts to bear fruit, we must create the appropriate cause. I’ll talk more about this later. There are many more Dharma aspects to the particular form of practice that is fund raising, the perfection of asking, and I encourage you to study teachings on giving and related subjects and think about them in your analytical meditations. But don’t meditate with a pad and pencil beside your cushion; once you realise the benefits of fund raising in meditation, you’ll never have to write them down. Finally, as food for thought, there’s a little booklet called Dana: The Practice of Giving (Wheel Series 367/369, Buddhist Publication Society, Candy, Sri Lanka), which contains some excellent teachings on giving and many scriptural references. WHAT MAKES A GOOD FUND RAISER? There are certain qualities that really help you be a better fund raiser. Some you have; some you can learn; some you can only dream about. A good fund raiser has lots of energy, is well organised, possesses excellent people skills, that is, is a warm person and makes friends easily. People give to people they like. As Lama Zopa Rinpoche always says, the best way to be liked is to have a good heart. Doesn’t it always come back to practicing Dharma? Credibility For us, the ideal fund raiser is a Dharma student with devotion to Lama Zopa Rinpoche, a long history of commitment to the FPMT and the study and practice of Dharma, and deep involvement in the centre’s activities. An experienced ex-director, perhaps. People have to feel that the person asking them for money really believes in the cause. As a fund raise, you can’t really ask others to do more than you’re doing yourself. So make sure you do a lot. As Lama Yeshe said, “Action is everything.” It follows from this that major donors could very well make excellent askers. They can go to their friends and say, “I gave this; do you think you could match it?” or something like that. See if any of your major donors would be open to doing this for you. You wouldn’t need too many of them to say yes to get a great result. If your efforts to involved committed supporters in the centre have been successful, some may well be willing to try. Ask. Therefore, sincerity is very important and comes with pure motivation. Proof: to date, Lama Zopa Rinpoche has been by far our most successful fund raiser. Try to appoint the most credible student at your centre as your fund raiser. (see also Lutheran Layman’s League (Australia) information kit, pages 4-5, for a long list of other desirable qualities) 3 HOW TO APPROACH FUND RAISING? Approach it systematically, thoughtfully, and as a business. And if your organisation has taxdeductible or similar status, whatever else you do, you are certainly also in the business of fund raising: your centre is tax-deductible to make it easy for people to give you money, so it doesn’t make sense not to ask. Actually, your tax-deductible status isn’t the main reason individuals give you money, but many trusts and foundations can give only to such exempt organisations. Thus, you are limiting your options if you eligible but don’t register. Develop a business plan, with a budget, clearly defined targets, a projected (and later actual) cash flow, and a realistic strategy of reaching out. Equip yourself with whatever tools you’ll need; you can’t do it without a computer. Measure your progress carefully. Get help of a good graphic artist (free, if possible, but in the long run it’s better to pay for good quality than have some well meaning student donate art work that you don’t like). The sooner you can present a professional image, the better. That doesn’t mean expensive. At first, avoid expensive at all costs; later, special occasions may demand expensive, but never be extravagant. Most of the people you’re trying to reach will be put off by ostentation. Become familiar with the history of the FPMT and the centre. You can get a lot of information from the FPMT handbook: read what Lama Yeshe and Lama Zopa Rinpoche have said about the organisation and working for it. It’s very inspiring. Your inspiration will come across to your donors. Make a display kit containing information about the centre, the FPMT, the project you’re raising funds for, and anything else you feel is relevant – covering letter from yourself, a photocopy of a newspaper article about your centre, an excerpt from a teaching – and use it in personal interviews or to send out through the mail. You might want to create a one-page fund raising document explaining why the centre exists, who it serves, how it helps, what are its goals – immediate, one year, five year and remote – what benefits accrue to the various levels of contributor, and perhaps even some upcoming projects and how much you need for each. WHY DO PEOPLE GIVE? This has to be one of the most researched questions in fund raising, but I have yet to see the main reason that people give listed in any book or paper on the subject. The main reason people give is because they can’t say no to the person asking. Build your strategy on this axiom. You have to make it as hard as possible for people to say no. (see also Babson (USA) folder: Reasons People Give; and Lutheran Layman’s League (Australia) information kit, page 3-4) WHO TO ASK? This, of course, is the fund raiser’s eternal quest. You are more likely to get a donation from someone who has given to the centre before than from someone who never has. Therefore, always go back to your previous donors first. But while doing this, you must also be continuously broadening your base of support. Start out by making a list of all those who have given to the centre before, with the amounts they have given beside their names. Arrange the list geographically (you should plan to travel!). Obviously, 4 people who support the centre are the best prospects, but try to involve all your benefactors in the centre somehow or other. A good time to go to students of the centre for help is at the end of the course. Many FPMT centres have been successful with an impassioned please for assistance at this time. You can ask for both immediate donations and pledges. See the sheet on the Heart-Spoon fund raising for an example of a course-end appeal that worked. Chenrezig Institute, for one, raised quite a lot of its early money for building the centre in this way. If any of your students own businesses, they may want to become corporate sponsors of the centre. Some businesses will match the donations made to a charity by any of their employees. See if any of your students work at companies like that. See if you can find other businesses to support you in some way. Perhaps you can find donors to issue “challenge” or matching grants, where they offer you a donation if you reach some particular goal; for example, “Double your membership this year and I’ll donate $5,000.00,” or “If you raise the money to pay $10,000.00 off our mortgage by the end of the year, I’ll donate $10,000.00 myself.” Here you are challenged to attain some goal you’d want to attain anyway, but there’s an incentive to try harder; and you can use the fact of the grant to stimulate donations: “Because of this grant, every dollar you give becomes two.” Some centres might object: “Our centre is in India; we can’t find sponsors here.” But Indians don’t come to the centre anyway; it’s mostly Westerners and Asians. Form a Friends of Tushita club, comprising those satisfied individuals who have benefited from the centre and gone back to their wellpaid jobs at home. Collect as much information about them as you can before they leave; ask if they’d like to become Friends of the centre, which would entail a yearly pledge, and offer to raise money for you in the West, or whatever else you can come up with. Everybody can find something they can do: make a plan, put it into action, and follow through. It’s as easy as that. In general, you can go to individuals, government organisations, foundations or other grantmaking institutions, and other Dharma groups. In Italy, some religious organisations get big money from the taxation system. Not Buddhists, yet, but perhaps soon. But note that as far as donations are concerned, at least in America, individuals give far more than all other sources of funding combined. Still, you should find out about any governmental programmes that might apply to you, especially if your centre is a hospice, a leprosy centre, or something like that. You can also go to your local library and research foundation directories, which contain information about the objectives of grantmaking foundations and how much they gave to whom (look under “philanthropy”). You can see if there are any that support Buddhist causes (there usually aren’t). Seek the advice of other Dharma centres in your area. Find out the names of as many Dharma benefactors as you can and gradually try to meet them. Network (vb.); in a way, you have to create your own little world. The world of planned giving is too complex for us to deal with here, but I have brought a little material on it with me. However, you should definitely explore every avenue. Imagine that when you got home from here, you learned that somebody had left your centre $100,000.00 in their will, because ten years ago, someone from the centre had asked. We have to be thinking far more than ten years ahead, so start cultivating committed students now. It takes people years to decide even to leave the centre in their will. Get a wills brochure made; the Karuna Trust brochure that I showed you before is a nice example. I will say a little more about planned giving and will brochures later. 5 There are also magazines and journals published for fund raisers, like the ones I’ve brought from Boston. Check to see if there are similar publications where you come from. As you will see, they contain lots of useful information, and you can also find out how real fund raisers think! Your best chance of receiving a significant gift comes from a one-on-one meeting with a sympathetic individual. Once you have met such a rare and precious one, cultivate the relationship very carefully. If you do, and the karma’s there, the result will likely be much greater than the results of a year’s direct mail (which you still have to do!). Therefore, you should spend a significant proportion of your time on seeking out new contacts (they call it “donor acquisition”). At Wisdom, we cast a wide net by advertising, our need for support in our several-times-a-year mailings – each of which reaches tens of thousands of reader – and in the backs of our books, which probably reach even more. We have yet to find a major benefactor this way, but these efforts bring welcome and much appreciated smaller amounts and help us identify people who want to give a least a little money to Wisdom. The task is then to gradually increase their commitment: get them to give more, get them to give regularly. Most other centres do not have Wisdom’s easy means of spreading their message, and what the above is telling you is that you should concentrate your efforts on identifying potential individual major donors. One way of simultaneously spreading the Dharma and raising money for the centre is to provide Dharma teachers to certain adult education programmes. In Boston, for example, there are several – such as the Cambridge and Boston Centres for Adult Education and Interface – which pay teachers several hundred dollars for courses on Tibetan Buddhism. The teachers provided by your centre would agree to donate their fees to the centre. A regular arrangement with your local adult education centre would provide not only a small cash stream for your own centre but would also build awareness of the centre and introduce many new people to it. As each centre’s situation is so different, I don’t think it’s useful to go into other details of how to meet new people here. If anybody wants to know what I do, I can tell them later. Many donors will drop off your list each year, so you do have to keep reaching out. Remember: money isn’t given, it has to be raised. Finally, remember that there is hot competition for Dharma dollars. You are up against other Dharma centres (sometimes your own!), Tibet causes, non-Buddhist organisations such as AIDS charities, Greenpeace, Amnesty International, and so forth. Like you, all these organisations need money. Everybody needs money. So people aren’t going to give you money just because you need it. You have to distinguish your centre from other causes. HOW TO ASK? This, in turn, is the fund raiser’s most sought-after skills. But you certainly do have to ask. Lama Yeshe always used to say that people want to help, but since they don’t have psychic powers, they need to be told how they can. Lama would exhort us to post wish lists in the centre’s entrance. Here you can ask not only for the material things your centre needs – desks, beds, computers, and so forth – but you can also list various other things people can sponsor – books for the library, items for the gompa, support for your geshe and translator, sponsorship of certain teachings or you newsletter, and the like. As usual, the list is endless, so it varies regularly. Every month, for example, you can also feature a different item needed by the centre to which people can contribute; establish a Wish of the 6 Month Club. Changing your appeals like this will attract the attention of people of varying interests. Once you’ve caught them, make sure you remember who they are. Near the wish list can be a table with centre brochures and other literature that will educate newcomers about Buddhism and the centre. You can leave any current fund raising materials there as well. You might also want to create other pamphlets, such as “What to expect when you visit Tara Institute” and “A Buddhist attitude towards money,” like the Episcopal ones I have here, as part of the important process of creating an atmosphere conducive to giving. And while we’re still here, try to make your centre’s entrance hall as peaceful and as spacious as possible, so that whoever comes in will automatically feel a good vibration. However, there are three main ways of asking people for money. In ascending order of efficacy, they are: by mail, by telephone, and in person. Money by Mail You can send someone a mass mailing, a fund raising package, or a personal letter. It is very easy for that person to ignore it. There’s no hurry to respond; the person probably gets several requests a week, if not a day; and your carefully crafted mailing will gradually get buried under a pile of other unanswered stuff or simply chucked out. You are unlikely to find a major donor in this way. Nevertheless, mailings of one sort or another and the development of an excellent mailing list are an indispensable part of fund raising. Any well done direct mailing campaign will fertilise the ground and at least pay for itself, and direct mail is probably the best way of finding first-time donors and building your list. People who give once are more likely to give again. People who give again may become regular donors. Regular donors are your best source of major donors and people likely to be interested in planned, or deferred, giving. Establishing a pattern of giving in your supporters thus leads to bigger gifts and bequests. Also once a thoughtfully managed – i.e. targets well chosen – direct mail campaign has become established, it serves as a predictable (10-12% margin of error), dependable, durable and growing source of steady income for the centre. Think about your mailings in terms of mailings seeking new prospects and those to established givers. You may want to create them differently. You can also raise capital funds by direct mail. Knowing the total amount you need, break it down into realistic amounts from the largest to the smallest. For example, you could raise $5,000.00 by having one donation of $1,000.00, two of $500.00, ten of $100.00, and one hundred of $20 – or whatever figures you come up with. If your predictions are accurate, as the campaign progresses you can identify which category of donation is behind schedule and focus attention to it. Here is probably as good a place as any to mention building excitement amongst your members by tracking the progress of such a campaign by placing a highly visible barometer in your gompa or near the entrance of the centre. Make a cute Dharma one: track the level of incoming donations with a shine chart or something. You might even find a benefactor to fund this campaign for you (“Your $1,000.00 will bring us $5,000.00”). Fund raising announcements should be made in the centre newsletter, but alone they won’t do much. However, the newsletter is a good place to thank sponsors (unless they want to be anonymous) – not only is it their due, but my guess is that it will probably bring more donations from other people than any number of announcements. 7 Phoning for Funds It is harder for someone to turn you down if you call them up. You’re there on the line and it is more difficult for them to say no. I haven’t ever tried systematically raising money by phone, but some people might find it worth a shot. If possible, get some training in sophisticated telemarketing techniques before you start, even if you won’t use most of them and will probably have to tailor the rest of what you have learned to a Dharma situation. Most Buddhists I’ve met don’t like being pressured. Again, it’s unlikely you’ll get any major donations over the phone alone. The best use of the phone is to stay in touch with benefactors or to follow up letters or other mailings you’ve sent out. Call major donors regularly. A mailing followed by a phone call can be quite effective, especially if you’re threatening a visit. Remember the axiom? People give because they can’t say no to the person asking. Therefore, meet prospective donors face-to-face and make it impossible for them to say no. The most effective way to get people to say yes is to go and see them. Rather than have them come to your office, take the trouble to go to them. Once you’ve made that effort, they will be more likely to want to show their appreciation. Therefore, when the amount you’re after warrants it, go to visit your prospective benefactor, conduct the meeting as follows, and do whatever you can to avoid a no. Asking for money: the personal presentation When you go to meet a prospective donor, know how much you’re going to ask for. This means you have done thorough research and figured out the right amount to ask of this person, at this time, for this project. It is not a good idea to go for the maximum each time. Keep the interview warm, friendly, relaxed and informal, and never be holier than thou. Meditate on exchanging yourself with the donor to see what you’d have to say to get a yes. There are four stages to the meeting: 1. Engage the donor in personal conversation for ten minutes or so. Ask all about them; their lives, their family, their work; how they got involved in Dharma, in the centre. Bond with them for a while. 2. Tell them all about yourself, where you come from, what you used to do; how you met the Dharma, your teachers; how you got involved in the centre. Talk about your commitment to the Dharma and to working for the centre. Here is where you show how credible you are, but humility is the key. 3. Next you have to make your case. Be positive. Don’t focus on the problems or money but on the result you’re trying to achieve; this is vajra fund raising. If this is the first time you’ve met the person, describe the FPMT and your centre (using your display kit, maybe a video of the centre, and any other relevant materials you have). Be clear and convinced of the benefits of the Dharma, the FPMT, and your centre. Describe your centre’s activities and how much good they do, appealing to your donor’s interests. Mention any underlying problems and how you intend to solve them. Give a brief run-down of the centre’s financial situation and where you get your money from. Explain why it is necessary to raise funds and exactly how this person’s donation will help. If it’s appropriate, let the donor know what other people are doing for the centre. Point out that most of the people who work for the centre are volunteers, and that even the geshe gets only a small stipend. It should become clear that the centre depends on a small number of 8 highly committed individuals and that donations are not wasted but well spent, as intended. You should also address the donor’s usually unasked question, “What do I get out of this?” Your answer will depend upon how good your research has been. Decide which of the various ways that you thank benefactors are appropriate for this occasion and skilfully lay them out. 4. Ask for the donation. Again, let the donor know how much the donation will mean to the centre and how much you want. Make sure you get not only a promise to give but a commitment to a certain sum. If donors don’t want to be pinned down and say they need time to think about it or talk to their accountant, ask what’s the minimum they’ll give. If you don’t walk out with a figure, know that you’re going to finish up getting less than you otherwise would have. As soon as you get back to your office, write the donor. Thank him or her for having taken the time to meet you, say how much you enjoyed your time together, and in the letter, summarise your recollection of the meeting you’ve just had. If you received the donation, send sincere thanks and a receipt, along with any other materials or books you might have promised them. Keep them informed as to the progress on the project to which they’ve contributed, always emphasising positive results and your appreciation of their help. Write even if you were turned down. It is extremely important to develop a good relationship with your benefactors and to communicate with them politely, humbly, and gratefully (while trying to retain your dignity!). Other things you can do Having stressed the importance of the personal interview in the solicitation of major donations, let’s look at some of the many other things waiting to be tried. You can hire a skilled professional such as a fund raiser or a grant writer. Professional fund raisers usually take a percentage of what they raise, but if they go beyond your own pools of donors, it’s well worthwhile. Usually, of course, the first thing they’ll ask for is your own mailing list, but it is better if you can get them to reach out to new people. They may, however, take on only major appeals, such as the Maitreya Project, where there is the potential of high returns. As I mentioned before, you can also investigate the various options around planned giving in your country, such as wills, estate plans, bequests, and legacies. Planned giving refers to people making a conscious decision to leave the centre in their will or to take out a life insurance policy with the centre as the beneficiary. Remember, such gifts are more likely to come from your committed members, so make the what-is-usually-viewed-as-delicate decision about when and how to ask them. The Christians are very up-front about using death as the incentive. Surely we have the best death meditations ever! In the Episcopal Church’s wills pamphlets, they say familiar things like: “We brought nothing into the world and it is certain we can carry nothing out” and “Death comes uninvited, and usually before you are ready for it.” They say that we have the power, the right, and the responsibility to decide how the goods that God has given us stewardship over – we don’t own them, we only collect them during our short lives – will be distributed after we die. “…all of us will some day leave behind all of our worldly possessions,” “no estate is too small for God; we all have something we need to share,” and “it’s simply amazing how many men and women try to ignore the inevitable, and then die without legally disposing of their property” may also be found. We study and meditate on these and similar teachings but seem reluctant to remind people that they’re going to die and to ask them to leave something to the centre. If we don’t ask them, they won’t. I mentioned will brochures before. At Wisdom, we’ve been working on our own. It’s called WIZWILL. The first, uncorrected draft goes something like: “Getting old? Got bags of money? As the doors to the intermediate state will creak open, let Wisdom 9 lighten your load. At great expense to the management, we introduce WIZWILL, our answer to that common and worrying question “What should I do with my post-bardo dollars?” WIZWILL is the perfect receptacle. Let us hold your funds until you drop in again the next time around; it’s the perfect answer to not being able to take it with you. But there’s no time to waste! You have a perfect human rebirth, death is definite, and your luck’s about to run out. So before your elements absorb and you can no longer speak, call our toll-free numbers and ask for Dr. Death. It’s a WIZE decision. If you’ve got the will, we’ve got the WIZWILL.” (With apologies to Neil McCarthy) You can inform lawyers at large of your existence as a Buddhist charity so that they can inform Buddhist clients who might be making a will. In London we advertised in a sort of non-profit yellow pages – they gave you a display ad and a column of editorial copy about your cause. This book was sent annually to every lawyer in the country. We were the only Buddhist organisation in it, and I think we received £500 once, but soon after that we closed down and moved to Boston. (See also Lutheran Layman’s League (Australia) information kit, pages 25-29, and the Uniting Church’s brochure “Money for the Church Ministries” and the pamphlets enclosed with it for more information about planned giving and the Christian church’s approach to it) You can organise events of varying size. If they’re major, involving celebrities and large halls and you manage to sell all the tickets, you can both make some money and raise the centre’s visibility as well. Sometimes you can launch a capital campaign with an event or party for your supporters. Smaller events and things like raffles and sales of donated goods can be organised by volunteers. They’re worth doing for the camaraderie as well as the money they bring in. There are many one-off events you can organise; you can delegate a volunteer events committee to run them frequently (oneoftens?). In the FPMT, we also have the advantage of being able to participate in international fund raising events, such as the Repaying the Kindness at Saka Dawa Fund (RK@SD). We’ll be talking about this in a later session, but I just want to say here that if we all work at it together, we can create vast amounts of merit and build this fund up into something that will really help us all. I am convinced that by participating in a cooperative venture such as this, each centre creates the cause for success in its own fund raising efforts. Finally, the cutting edge of fund raising: e-mail. I haven’t received any junk e-mail yet, but the day will come. With electronic malls growing apace, can their electronic mail be far behind? However, I have sent out some of my own in that I’ve started fund raising by e-mail, and I’m not sure where it will finish up ranking amongst the big three: mail, phone, and personal. And a note on how to ask. Don’t rush an appeal. Panic makes benefactors nervous. Make sure you never get that desperate. A dense, negative, one-page letter full of gloom and doom – “the centre will fail unless you send $1,000.00” – rationalisations, guilt, and fear will not raise money. People don’t want to put money into such a risky proposition. You must be confident and the centre must appear substantial. WHAT TO RAISE FUNDS FOR? Usually it is better to identify a project, some particular need, rather than to ask for general funds for the centre. Try to match the project with the appropriate source of funding. A capital campaign is a drive to raise funds for a specific project, usually a big one – like buying a house for the centre – where you need a large amount of cash. These are usually called restricted funds. Don’t try to raise money to retire old debt. General (unrestricted) funds, which are just as important as large gifts, can be raised through membership (which is definitely an important means of fund raising), direct mail, donations at the door, 10 and so forth. You do need to establish a strong flow of regular funds, especially from regular members and more committed supporters. Loans. As a last resort, you can borrow money interest-free – preferably for a limited project where the repayment stream has been clearly identified – or raise money to pay the interest on a loan, effectively making it interest-free, but as recommended principle, try to avoid putting the centre into debt, and always check with your treasurer first. PREPARING THE GROUND If you want to develop the centre, you should try to raise its profile as high as you can. Use the media for free publicity; perhaps someone would sponsor a professional public relations person for a day to work with your centre’s publicist, or you could ask an advertising agency to run a pro bono campaign for you. For example, in America, the Snow Lion newsletter carries news of Dharma appeals free of charge. What you run may not bring any direct result, but such publicity should be a part of any major fund raising effort. You might even consider using the paid Buddhist media, such as Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Investigate the possibilities in your part of the world. Check into getting a home page about your centre on the Internet. There may non-profit organisations to help you get set up. You should also advertise your centre and its programs on the many Buddhist and Tibetan-related electronic bulletin boards around the world. The centre should support freedom for Tibet and keep a high profile at rallies. Be part of a group organising visits of His Holiness the Dalai Lama at your country. Get involved in charitable and community activities. I’m sure you can think of more things to do than I can. Apart from the merit, all this is also creating the conditions for your fund raising efforts to bear fruit. However, as essential as they may be, all those activities are just external. If people give because they can’t say no to the person asking, then people receive because they have created karma. To enjoy success, you have to create the karma for success. Try to run a generous centre…as generous as your treasurer will allow. If you and the people connected with your centre haven’t created the karma to receive the funds, no matter what you do, they won’t come. This point obviously needs a great deal of attention, but knowledge of karma is our secret weapon. At Wisdom, while we try to remember to motivate and dedicate, we certainly act. We give away about 300 copies of each new book: to teachers, Dharma centres and monasteries, benefactors, Tibet offices, scholars, and many other people. We also provide free books to people in jail and to Dharma groups and individuals in Eastern Europe. We have published for free distribution more than 150,000 booklets of teachings by His Holiness the Dalai lama, and continue to do more. We also try to promote the FPMT; each book we publish contains information about the organisation and the address of the Central Office. We offer space in our office for Dharma teachings, and sponsor our own pujas as well as participating in all FPMT fund raising activities, such as long life pujas for our lamas and offering of lights to the great stupa in Bodh Gaya. We’ve also invested in some wealth vases. Each centre should allow for generous giving in its budget and offer its students the opportunity of participating. It’s our job to help people create merit. Decide from year to year what you can offer in the way of free teachings, no charges for the sangha, charitable works outside the centre – AIDS, homelessness, hunger, community involvement – and so forth. Make a consciously motivated effort to have the centre do some of these things. 11 HOW TO RUN YOUR FUND RAISING OPERATION Become familiar with the various laws around this issue and always keep your centre director apprised of what you are doing. If your centre is not yet registered or is registered in a disadvantageous way, see if it can become a non-profit organisation, a charitable trust, a religious association, an educational institute, or something like that. Register accordingly to the laws of your own country in such a way that your centre becomes an attractive recipient for gifts of various kinds, principally money. Learn just a little more than you need to know about your country’s tax code. And absolutely consult your centre’s accountant. Find out what receipts you have to issue and when, and what they must say. If you get this wrong, you may get into trouble with the authorities or have to return the money, and will almost certainly face high legal or accounting fees. Read books and articles about fund raising. Go to development conferences and seminars (development is an American euphemism for fund raising). Keep your eyes open for, collect, and analyse any helpful fund raising or other materials that will stimulate your imagination, which is the only thing holding you back. Many large organisations have been spending huge amounts of money developing and distributing fund raising materials for a very long time. Once you’ve trained your eye, you’ll find something you can use in most other organisations’ strategies and appeals. This is what we’ll do tomorrow. Record keeping You must keep immaculate records. There are several computer programmes for fund raisers (e.g. The Raiser’s Edge), but most of the ones I’ve seen are too big for us. It’s probably easier for you to create your own system, but I’m looking into the possibility of getting customised FPMT fund raising software for use in the Foundation. If we all use the same programme it will be much easier to help each other later. It should allow you to keep complete benefactor records and maintain your mailing lists, and have a spreadsheet to keep track of your budget, expenses, targets, donations, and so forth, and to make graphs and other visual displays for presentations to the centre committee and inclusion in your display kit. Divide your list according to the amount people give, decide how to handle each group, and keep a complete profile of each significant benefactor. You should know better than the donors themselves what they have done for the centre. Know how much they have ever given, when their last donation was, how much it was, what it was for, and where the project they donated towards is at. Know their personal details: name, address(es), telephone and fax numbers at home and at work, e-mail address, husband, wife, children, family situation, occupation, other interests, and so forth. I found it helpful at first to keep a day book. Every time I called or wrote to someone, I wrote it down. You can also write down all the bright ideas that will come to you out of the blue from time to time (I’ve had a few as I’ve been writing this). Thus, you have a record of who you’ve been in touch with, what you have to do next, what you’re expecting from them, and anything else about the communication you’re going to have to act on. Along with this, keep a “to do” list. Create a really good mailing list; it will probably be the most important thing on your computer. There are many simple programmes for list maintenance and list-management is an integral part of any fund raising software. Develop your list, analyse it, categorise your constituents, keep it clean. Learn to use your word processor’s mail-merge feature. For some important mailings or when you want to acquire new donors, you might try renting other lists, either directly from the owner or through a list broker. 12 GETTING HELP Typically, board members of a non-profit organisation are there for the three w’s: work, wealth or wisdom. Board members, trustees, and so forth, will often either donate money themselves or go out and raise it. If you can find a centre member with lots of wealthy, sympathetic friends or other contacts, you might want to invite that person to join your board. Delegating. Certainly get people to help you with menial tasks such as stuffing envelopes, but try to appoint surrogate fund raisers; that is, get others to ask for money on your behalf – people willing to go to their own circle of friends on your behalf or people living in another city that is still served by your centre. HOW TO THANK AND HONOUR YOUR BENEFACTORS How you thank benefactors depends upon how well you know them. Always be prompt, thank them in writing, and do whatever you said you’d do. Be friendly and stay in touch regularly. Once you have built your list to fifty or a hundred, you might want to consider publishing a quarterly fund raising newsletter. (See also Lutheran Layman’s League information kit (inserts) for guides to writing, laying out, and designing a fund raising newsletter and to seeking out material for it) How you honour your benefactors depends upon too many factors to go into here. What was the project, how much did they give, do they want to remain anonymous; always remember to ask. Chenrezig Institute recently built this incredible mani wheel inside a house with a green-tiled roof. People were given the chance to sponsor one or more tiles, and their names are forever linked with almost twenty billion mantras (which they were also able to sponsor). Again, at Wisdom, we have an easy way of showing our appreciation; we acknowledge the donor’s help on a special page at the front of the book. Many people are happy to see themselves linked in that way to a project they have supported, and it also gives others the opportunity of rejoicing at others’ generosity. Some might even think of doing the same thing themselves. We also make short-run special editions of certain books, each of which is numbered, as gifts for regular benefactors or other people important to us; these books are never sold. You can offer free or lifetime memberships, provide greater access to the teacher or centre facilities. Host dinners for small groups of benefactors, instigate some kind of ‘club’ for those who donate more than a certain amount, offer them front row seats at any special teachings or events you organise, and so forth. Whatever tokens of thanks you decide upon, remember to let the benefactor know about them when you are soliciting the donation. DONATIONS ARE PRECIOUS We have to respect the donations we get, and accept the great responsibility that comes with accepting a Dharma donation given with Mahayana motivation. It belongs to all sentient beings. We must therefore, ensure that it is spent exactly as the donor intended, and not wasted. LAMA ZOPA’S ADVICE Last year, I asked Lama Zopa Rinpoche what he thought the benefits of giving to Wisdom were. Some of what Rinpoche said follows, and you might be able to adapt the meaning of his holy words to your own situations. 13 “A Dharma book plants the seed of the path in the mind of the reader. That imprint actualised, realisations come, and liberation is attained. Books open the wisdom eye; you can understand death and the nature of the mind; they teach you how to develop compassion; they bring world peace. Wisdom publishes authentic Dharma books. When you read and practice them, you can understand karma, how everything comes from the mind, that the external cause is not the only one. This can lead you to a happy death and a happy rebirth. Book sponsors offer all the above benefits to others, cause them to open their minds. Each person transformed brings peace into the world. It becomes an extremely practical thing. Sponsoring books is for people who like to spread Dharma. If you organise a meditation course, only a few people get to hear the teachings, whereas if you publish a book, you can help thousands more. Books reach every corner of the earth. Until you change your mind – no matter how well-off you are – you still make mistakes in your actions. To stop your own suffering, you have to stop creating negative actions; to stop creating negative actions, you have to stop your negative mind. Books tell you how to do that.” RECOMMENDATIONS Here’s a shopping list of various things we could do together to develop our centres. The actual recommendation are in bold type. I think each centre should appoint a fund raiser whose only job at the centre would be to raise funds (as defined earlier). That person would also serve as the centre’s liaison with any FPMT global fund raising initiatives (such as RK@SD) or appeals from other FPMT projects (such as the Maitreya Statue, the Land of Calm Abiding, and the Free Food for Sera Monastery Fund). This fund raiser should immediately get a CompuServe e-mail account in order to network with other FPMT fund raisers. You will also need it to post messages about your centre on bulletin boards. The FPMT as an organisation could establish both a fund raising advisory board – comprising centre fund raisers and professional volunteers, if so desired – and an FPMT fund raisers association. The board would be available for consultation on and help with centres’ fund raising plans. The association could organise an annual meeting of FPMT fund raisers (perhaps at CPMTs), and the workshops from time to time. We could also establish a fund raising headquarters, where we could keep the records of FPMT centre appeals and other materials through the ages, with their successes and failures: a historical and practical archive. Updated computer disks with this information could be made available to centre fund raisers; they could also contain Lama Zopa Rinpoche’s previous advice on the benefits of building statues and stupas, for example, and we could ask him to give further teachings on all aspects of giving. We could also make an instructional fund raising video for use in FPMT centres. We could also publish a regular fund raising section in Mandala and as mentioned earlier, get customised FPMT fund raising software for PCs and Macs. Finally, we could ask the Central Office to provide a fund raising advisor, to come to centres to help them with campaigns. A percentage of the identifiable results would be returned to the Centre office, and success in this endeavour would ensure that the centre, our administration, and the entire organisation prospered. 14 IN CONCLUSION Obviously you don’t have to do everything I’ve mentioned. I meet Wisdom’s targets using just a few of these methods. Find what works for you and develop that. I just wanted to give you an idea of the scope of the Dharma fund raising and a way to approach it that has worked for us. Nicholas Ribush Pomaia, 1995 A FINAL NOTE The above has been put together somewhat hastily, can be much improved, and is intended mainly for the use of participants in CPMT 1995. References to the meeting are obvious. If people think it’s useful and are willing to contribute their input, I could try to develop this material further into some kind of FPMT fund raiser’s handbook. Anyway, the important thing is to use your imagination (this is not a cookbook) and input some of these techniques into practice right away and see what happens. This is just the beginning of what I hope will become a flourishing FPMT activity, and we can gradually develop better fund raising strategies together, as we go. I would also like to thank Kimball Cuddihy, De-Tong Ling, South Australia, for materials provided during CPMT ’91 at Tara Institute, Melbourne. (For a glossary of fund raising terms, see Lutheran Layman’s League (Australia) information kit, pages 40-52). 15