Literary Devices

advertisement

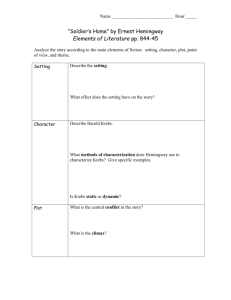

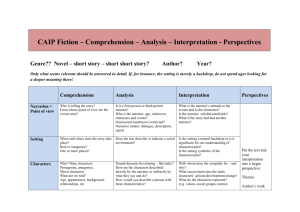

Literary Devices: Fiction Fiction terms (most from Bedford 9th edition: all pg. #’s are from this unless otherwise noted) PLOT section Plot is the author’s arrangement of incidents in a story (73) -chronological (linear) arrangement happens first, then second, and so on (“Rip Van Winkle” for example) -arrangement can be different however; nonlinear structure, back and forth between past and present (Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily”) or circular, (Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five) in media res: latin term for when stories begin in the middle of things (Updike’s “A&P”) (73) flashback: a device that informs us about events that happened before the opening scene of a work (73) character: an imagined person in the story (73) exposition: background information the reader needs to make sense of the situation in which characters are placed (78) rising action: complication that intensifies the situation (78) conflict: struggle between opposing forces (79) --external conflicts may place the protagonist in opposition to another individual, nature, or society (80) -internal conflicts: in such a case, some moral or psychological issue must be resolved within the protagonist (80) foreshadowing: a suggestion of what is yet to come (79) protagonist (or sometimes hero): central character who engages our interest and empathy (79) antagonist force that opposes the protagonist (79) suspense when the story creates emotional tension for the reader (79) climax is the moment of greatest emotional tension (79) 1 resolution (aka denouement: which is French for “untying of the knot”): …the…well, resolution, of the conflict (79) CHARACTER section Characterization methods by which a writer creates people in a story (121) Some of these methods are: Direct characterization: the author tells us the traits Indirect characterization: the author shows us the traits --using names to hint at character traits --what characters say (or what others say about them) or do --physical description (124) Characters whose actions are motivated have reasons for how they behave and what they say. (125) If adequate motivation is offered, we find their actions plausible, believeable. (125) And when what they do and say works together in these ways, we find them to be consistent characters. In Absurdist literature, characters are often alienated from themselves and their environment in an irrational world. In this world there is no possibility for traditional heroic action. Characters often do not behave in realistic or consistent fashion. And in this type of lit, we often find an antihero who has little control over events. (Billy Pilgrim from SH5) (125) a dynamic character undergoes some kind of change because of the action of the plot (Huck Finn in response to Jim) a static character does not change (Tom Sawyer just loves adventure) (also, the protagonist in Faulkner’s “A Rose for Emily” is static, but this serves a reinforcing purpose in the story…she resists all change) (125) a foil helps reveal by contrast the distinctive qualities of another character (Tom is a foil to Huck) 2 a flat character embodies only one or two qualities, ideas, or traits that can be readily described in a brief summary. One-dimensional. (126) Some flat characters are stock characters; types rather than individuals, such as the loyal servant, the mean stepfather, the henpecked husband, the sadistic army officer. Round characters are more fully developed than flat characters. Multi-dimensional, many traits. (126) SETTING terms Setting is the context in which the action of a story occurs. Major elements of setting are time, place, and the social environment that frames the characters. (184) Mood or atmosphere is the feeling created in the reader by a passage (“somber”, “threatening”, etc.). Setting can contribute to this. POINT OF VIEW terms Point of view refers to who tells us the story and how it is told (212) Narrator is the teller of a story (212) THIRD-PERSON NARRATOR (nonparticipant) (213-214) 1. Omniscient p.o.v.: all-knowing; the narrator takes us inside the character(s) a. editorial omniscience is when the narrator evaluates a character for the reader b. neutral omniscience is when the narration allows characters’ actions and thoughts to speak for themselves 2. Limited omniscient p.o.v.: narrator takes us inside one or two characters (Ernest Hemingway’s “Soldier’s Home” a. Stream-of-consciousness technique takes a reader inside a character’s mind to reveal perceptions, thoughts, and feelings on a conscious or unconscious level. Complete sentences may give way to fragments and free associations (see Joyce’s Ulysses) 3 3. Objective p.o.v.: narrator is outside the character(s). Does not see into the mind of any character. Narrator reports action and dialogue without telling us directly what the character feels and thinks. We observe the characters in much the same way as we would a film. FIRST-PERSON NARRATOR (participant) (215) The I presents the p.o.v. of only one character’s consciousness; reader is restricted to perceptions, thoughts, and feelings of that single character. 1. Major character 2. Minor character Unreliable narrator -might lack self-knowledge, or might be innocent and inexperienced: a naïve narrator such as Holden Caulfield from Catcher in the Rye. Might be biased. Might be mentally “unfit”. SYMBOLISM terms A symbol is a person, object, or event that suggests more than its literal meaning (262) Conventional symbols are those widely recognized by a society or culture. The Christian cross, the Star of David, a swastika, a nation’s flag, a wedding ring, all have meanings understood by large groups of people. Recognize that individual cultures sometimes have their own conventions (some Eastern cultures associate white rather than black with death and mourning). (263) A literary symbol can include traditional, conventional, or public meanings, but it may also be established internally by the context of the work in which it appears. (In Ernest Hemingway’s “Soldier’s Home”, Hemingway overturns the traditional associations of home with safety and security; instead, the soldier’s home becomes symbolic of erroneous presuppositions due to blind innocence, ssentimentality, and smug middle-class respectability). A literary symbol can be a setting, character, action, object, name, or anything else in a work that maintains its 4 literal significance while suggesting other meanings. Symbols cannot be reduced to one meaning; they are suggestive rather than definitive. When a character, object, or incident indicates a single, fixed meaning, the writer is using allegory rather than symbol. (264) THEME terms Theme is the central idea or meaning of a story. It provides a unifying point around which the plot, characters, setting, point of view, symbols, and other elements of a story are organized. Distinguish between the theme of a story and its subject; they are not equivalents. THEME STATEMENTS (from Klinge/Perrine p.195-197) 1. Theme should be expressible in the form of a statement with a subject and a predicate. “War” and “Disillusionment” are subjects in Ernest Hemingway’s “Soldier’s Home”; a thematic generalization of the story is more like this: “the brutal experience of war can alienate a person from those—even family and friends—who are innocent of war’s reality.” 2. The theme should be stated as a generalization about life. In stating theme we do not use the names of the characters or refer to precise places or events, for to do so is to make a specific rather than a general statement. 3. We must be careful not to make the generalization larger than is justified by the terms of the story. Use some, sometimes, may rather than every, all, always. 4. Theme is the central and unifying concept of a story. Therefore: (a) it accounts for all the major details of the story. If we can’t explain the bearing of an important incident or character on the theme, our interpretation is probably partial and incomplete. (b) The theme is not contradicted by any detail of the story. If we have to overlook or “force” the meaning of 5 some significant detail in order to frame our statement, then our statement is defective. (c) The theme cannot rely upon supposed facts—those not actually stated or clearly implied by the story. The theme exists inside, not outside, of the story. The statement of it must be based on the data of the story itself, not on assumptions supplied from our own experience. 5. There is no one way of stating the theme of a story. The story is not a guessing game that is supposed to yield some magical verbal formula; as long as the above conditions are fulfilled, the view may be stated in more than one way. 6. We should avoid any statement that reduces the theme to some cliché saying, such as “You can’t judge a book by its cover”. This is reductive and wastes the possibility of a fresh perception. 7. Use quotes/key terms/phrases (perhaps the title) from the story. Ground your statement in the language of the story. KLINGE’S FORMULA FOR THEME STATEMENT Klinge’s Theme Statement Formula When <define the protagonist> comes in conflict with/encounters <define the antagonists/antagonistic forces> in a situation in which <define the relevant circumstances/conditions/setting> the result may be <explain/define the outcomes, ending points, epiphanies, dynamic changes in character, resolutions, conclusions> “When a person like the protagonist encounters a challenge like this one under these conditions the result may be that something significant occurs.” The final section is the most analytical and most important. Often, your statement will extend into another sentence (or more) with that portion. It is less important that your statement be elegant than it be comprehensive. Since it is a formula, the result will be formulaic. Ultimately, you should go beyond the formulaic phrasing and structure. 6 STYLE, TONE, IRONY terms Style refers to the distinctive manner in which a writer arranges words to achieve particular effects. Individual word choices, length of sentences, structure, tone, and the use of irony. (329) Diction refers to a writer’s choice of words. (330) Tone is the author’s implicit attitude toward the people, places, and events in a story. Dependent on the context in which a statement appears. (Consider if, in real life, I told you “you’re going to fail the next exam”; this could be cruel, indifferent, or humorous depending on the context and the way I say it) Irony is a device that reveals a reality different from what appears to be true Verbal irony consists of a person saying one thing but meaning the opposite. Sarcasm is a common example in everyday life, but in literature is often more subtle and restrained. Situational irony exists when there is an incongruity between what is expected to happen and what actually happens. Dramatic irony creates a discrepancy between what a character believes or says and what the reader understands to be true. 7