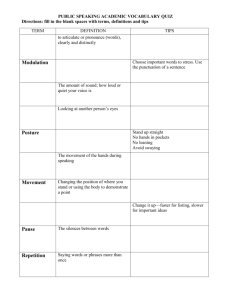

General Teaching Tip

advertisement