12591,"verbal irony in oedipus rex",5,4,"2000-11-17 00:00:00",50,http://www.123helpme.com/view.asp?id=79689,3.4,32600,"2015-12-22 11:51:49"

advertisement

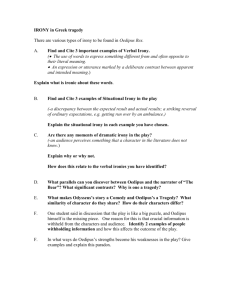

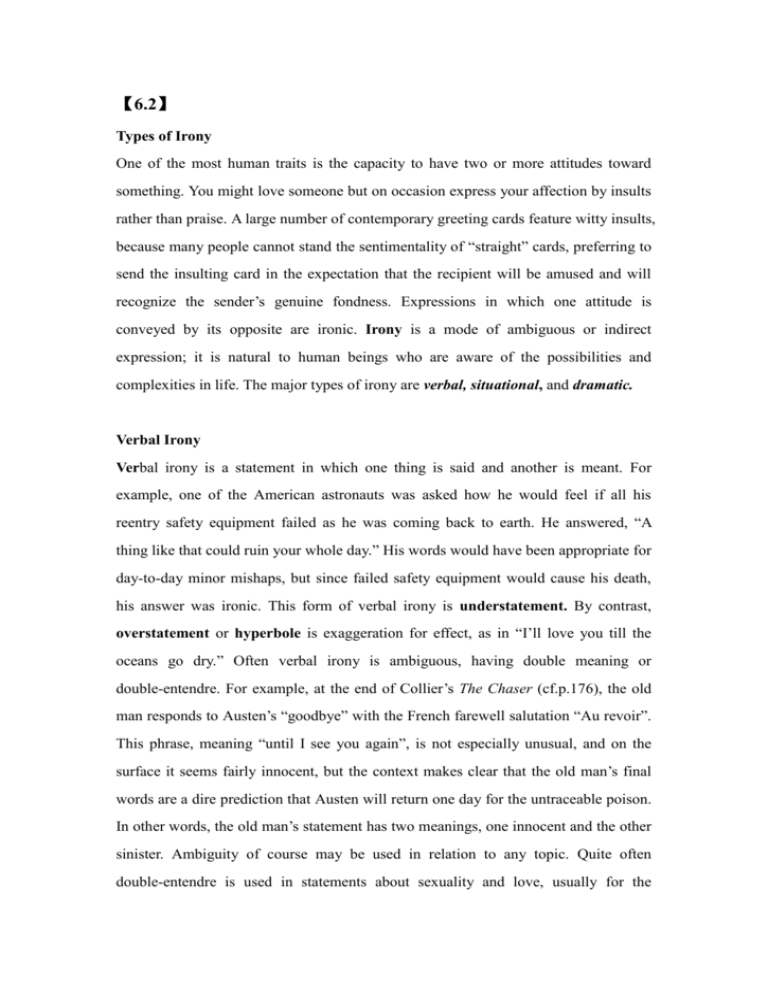

【6.2】 Types of Irony One of the most human traits is the capacity to have two or more attitudes toward something. You might love someone but on occasion express your affection by insults rather than praise. A large number of contemporary greeting cards feature witty insults, because many people cannot stand the sentimentality of “straight” cards, preferring to send the insulting card in the expectation that the recipient will be amused and will recognize the sender’s genuine fondness. Expressions in which one attitude is conveyed by its opposite are ironic. Irony is a mode of ambiguous or indirect expression; it is natural to human beings who are aware of the possibilities and complexities in life. The major types of irony are verbal, situational, and dramatic. Verbal Irony Verbal irony is a statement in which one thing is said and another is meant. For example, one of the American astronauts was asked how he would feel if all his reentry safety equipment failed as he was coming back to earth. He answered, “A thing like that could ruin your whole day.” His words would have been appropriate for day-to-day minor mishaps, but since failed safety equipment would cause his death, his answer was ironic. This form of verbal irony is understatement. By contrast, overstatement or hyperbole is exaggeration for effect, as in “I’ll love you till the oceans go dry.” Often verbal irony is ambiguous, having double meaning or double-entendre. For example, at the end of Collier’s The Chaser (cf.p.176), the old man responds to Austen’s “goodbye” with the French farewell salutation “Au revoir”. This phrase, meaning “until I see you again”, is not especially unusual, and on the surface it seems fairly innocent, but the context makes clear that the old man’s final words are a dire prediction that Austen will return one day for the untraceable poison. In other words, the old man’s statement has two meanings, one innocent and the other sinister. Ambiguity of course may be used in relation to any topic. Quite often double-entendre is used in statements about sexuality and love, usually for the amusement of listeners and readers. Situational Irony The term situational irony, or irony of situation, refers to conditions that are measured against forces that transcend and overpower human capacities. These forces may be psychological, social, political, or environmental. For example, Collier’s story, The Chaser is based on the irony of situation in which an unrealistic desire for romantic possession leads people inevitably toward destructiveness rather than everlasting love. Such kind of situational irony connected with a pessimistic or fatalistic view of life is sometimes also called irony of fate or cosmic irony. Situational irony could of course work in a more optimistic context. For example, an average, or even blockheaded person could go through a set of difficult circumstances and be on the verge of losing everything in life, but, through someone’s perversity or through luck, might emerge successfully, as does Scoresby in Samuel Clemens’s story Luck (cf. P. 180). Such a situation could reflect an author’s conception of a benevolent universe, or, as in the case of Scoresby, a more arbitrarily comic one. Dramatic Irony Dramatic irony is a special kind of situational irony; it applies when a character perceives a situation in a limited way while the audience, including other characters, may see it in greater perspective. The character therefore is able to understand things in only one way while the larger audience can perceive two. The character Austen in The Chaser is locked into such irony; he believes that the only poison he will ever need is the one that will win him love, while the old man and the readers know that he will one day return for the poison. The classic example of dramatic irony is found in the play Oedipus Rex by Sophocles. All his life Oedipus has been entrapped by fate, which he can never escape. As the play draws to its climax and Oedipus believes that he is about to discover the murderer of his father, the audience knows that he is drawing closer to the point of his own self-destruction: as he condemns the murderer, he is also condemning himself. As critic Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg note in their study of narrative literature, The Nature of Narrative (1966), there are “in any example of narrative art…broadly speaking, three points of view---those of the characters, the narrator, and the audience.” When any of the three “perceives more---or less---than another, irony must be either actually or potentially present.” In any work of fiction, it is crucially important that we are able to determine if and how that potential has been explored; to overlook or misinterpret the presence of irony can only lead to a misinterpretation of the author’s attitudes and tone and the way he would have us approach and understand the work.