The Skinny on Writing Awesome Introductions and Conclusions for

advertisement

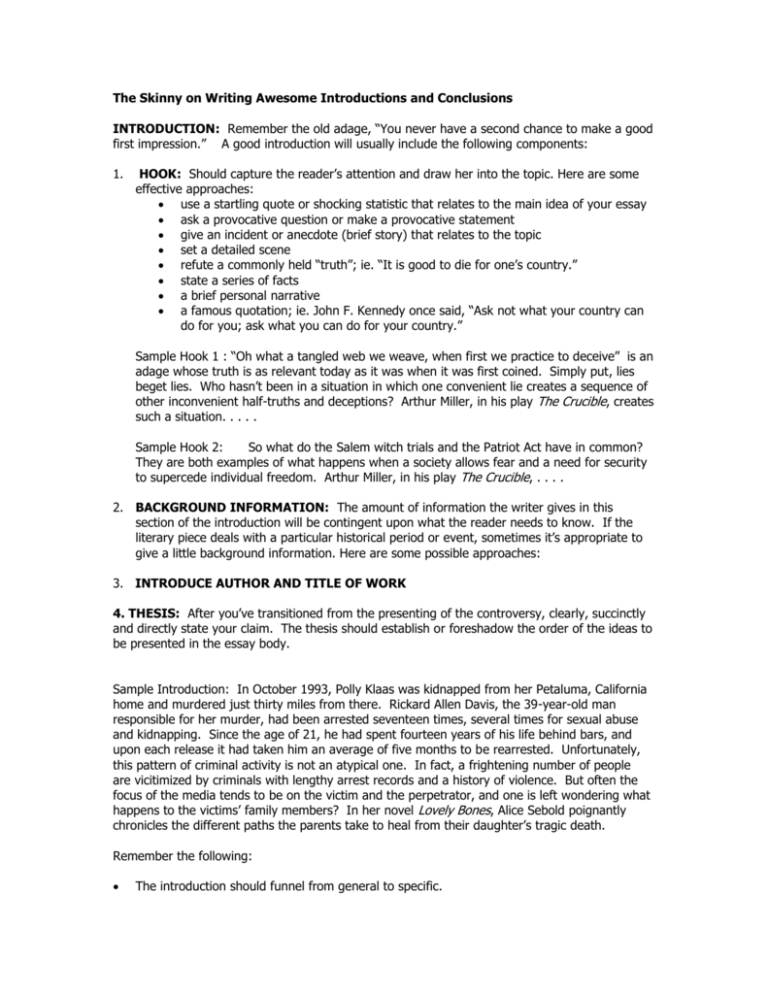

The Skinny on Writing Awesome Introductions and Conclusions INTRODUCTION: Remember the old adage, “You never have a second chance to make a good first impression.” A good introduction will usually include the following components: 1. HOOK: Should capture the reader’s attention and draw her into the topic. Here are some effective approaches: use a startling quote or shocking statistic that relates to the main idea of your essay ask a provocative question or make a provocative statement give an incident or anecdote (brief story) that relates to the topic set a detailed scene refute a commonly held “truth”; ie. “It is good to die for one’s country.” state a series of facts a brief personal narrative a famous quotation; ie. John F. Kennedy once said, “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” Sample Hook 1 : “Oh what a tangled web we weave, when first we practice to deceive” is an adage whose truth is as relevant today as it was when it was first coined. Simply put, lies beget lies. Who hasn’t been in a situation in which one convenient lie creates a sequence of other inconvenient half-truths and deceptions? Arthur Miller, in his play The Crucible, creates such a situation. . . . . Sample Hook 2: So what do the Salem witch trials and the Patriot Act have in common? They are both examples of what happens when a society allows fear and a need for security to supercede individual freedom. Arthur Miller, in his play The Crucible, . . . . 2. BACKGROUND INFORMATION: The amount of information the writer gives in this section of the introduction will be contingent upon what the reader needs to know. If the literary piece deals with a particular historical period or event, sometimes it’s appropriate to give a little background information. Here are some possible approaches: 3. INTRODUCE AUTHOR AND TITLE OF WORK 4. THESIS: After you’ve transitioned from the presenting of the controversy, clearly, succinctly and directly state your claim. The thesis should establish or foreshadow the order of the ideas to be presented in the essay body. Sample Introduction: In October 1993, Polly Klaas was kidnapped from her Petaluma, California home and murdered just thirty miles from there. Rickard Allen Davis, the 39-year-old man responsible for her murder, had been arrested seventeen times, several times for sexual abuse and kidnapping. Since the age of 21, he had spent fourteen years of his life behind bars, and upon each release it had taken him an average of five months to be rearrested. Unfortunately, this pattern of criminal activity is not an atypical one. In fact, a frightening number of people are vicitimized by criminals with lengthy arrest records and a history of violence. But often the focus of the media tends to be on the victim and the perpetrator, and one is left wondering what happens to the victims’ family members? In her novel Lovely Bones, Alice Sebold poignantly chronicles the different paths the parents take to heal from their daughter’s tragic death. Remember the following: The introduction should funnel from general to specific. Use transitions such as “furthermore,” “however,” “nevertheless,” or in spite of” to link one idea to another. CONCLUSION: Research shows that 80% of what a reader takes away from a written work will come from the conclusion; therefore, it is imperative that the conclusion be memorable. It should bring closure to the topic and drive home the writer’s point. Remember, too, that as with the introduction, audience awareness is critical. The typical structure of a conclusion funnels from specific to universal and contains the following elements: 1. Restatement or review of key ideas (Do not, I repeat DO NOT, insult the reader by restating everything you have just told him in the last five pages!) 2. General concluding remarks 3. Final statement Here are some approaches you might find helpful: Link to similar situations/events: Put the issue in a larger context by asking “How does this topic relate to what’s going on today?” or “How is this similar to what’s happening in other parts of the world?” For example, if you’re arguing to increase penalties in hate crimes, you might point out that hate crimes have increased worldwide. Just be careful not to go off on a tangent, or build a straw-man argument. Illustration: Use a relevant news item, story, incident or anecdote that vividly portrays the point of the essay. Be careful that the story clearly relates to the thesis and the rest of the essay or the essay will lose its focus. Prediction: the writer summarizes key points and makes a projection on the basis of these points. Again, be careful not to make any leaps in logic here! Hook and Return: This continues the anecdote, story, or incident that was begun in the hook in order to show the severity of the problem or to show how the outcome could have been avoided. Quotation: Quotations by well-known people can pull together essay ideas in an eloquent, profound way, just make sure the quotation is relevant to the topic of your paper. Note: If you’ve used this strategy in the introduction, do not use the same technique in the conclusion. Tips for writing conclusions: 1. 2. 3. 4. The ideas should funnel from specific to more universal. The conclusion should be memorable. Do not “fence-straddle”! You must take a stand! Do not use such monstrosities as, “In this essay, I have shown you. . . .” or “From the examples I have used above.” Works Cited BGSU Writing Lab Online. “How to Write a Good Introduction.” [Online] Available http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/writing-lab/gohow_to_write_a_good_.html , 1999. BGSU Writing Lab Online. “How to Write a Good Introduction.” [Online] Available http://www.bgsu.edu/departments/writing-lab/gohow_to_write_a_good_.html , 1999. Porter, Helen Hadley. MSU Writing Center: “Introductions and Conclusions.” [Online] Available http://English.Montana.edu/wc/info/strategies/intros_conclusions.html, March 30, 2004.