The Mind-Body Problem

advertisement

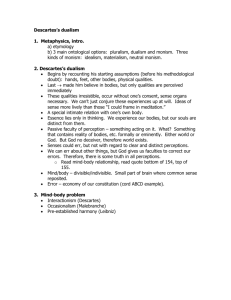

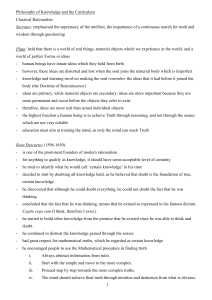

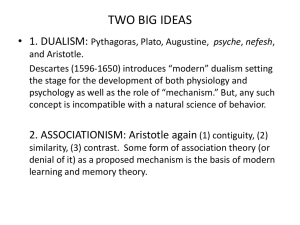

The Mind-Body Problem: Summary: The “mind-body problem” refers to the difficulty of explaining how the mental activities of human beings relate to their living physical organisms. Historically, the most commonly accepted solutions have included mind-body dualism (Descartes), reductive materialism (Hobbes) or idealism (Berkeley), and the double aspect theory (Spinoza). This problem has been a major concern of metaphysicians in “modern” times (i.e. since the 17th century): arose as a result of certain views of Descartes increasing knowledge about both mental and physical worlds has not answered it addresses the questions: “What is the fundamental nature of the mind and the body?” and “How are the mind and the body related?” Elementary observation of mental and physical events might lead to the suspicion that they are quite different; yet, they seem to be in some relation or have some influence on each other; how do we explain this? i.e. our scientific knowledge would seem to suggest that the physical world is inanimate, without purpose, and yet “determined” or fixed; it operates according to the laws of science the mental world, by contrast, operates through consciousness, planning, desire, intention, etc. though these worlds may seem to be quite different, experience indicates that they are interrelated or connected – when something happens in the physical world, this may change one’s thoughts or feelings in the mental world; similarly, a desire for light may cause one to strike a match in the physical world Descartes’ Mind-Body Theory: often blamed for the difficulties that arose from this problem o asserted that mind and body are 2 totally different types of being; they are different substances o from the “clear and distinct” idea that he had in his own mind, he decided that the basic feature of matter was its geometrical qualities (size, shape, etc.) the basic feature of mind was thinking according to Descartes, the essential property of a mind is that it thinks, and the essential property of a body is that it is “extended” (in space) Descartes further asserted that “mind” is never extended, and that “body” never thinks; in other words, the 2 realms of thought and extension are completely different o He went on to insist that all physical action occurs by the impact of one “extended object” upon another; since mental events are (by definition) NOT extended, how can there be any impact or contact between that whose nature it is to exist in space, and that which does not occur in space? How can an idea move a hammer, or a hammer strike upon an idea? Descartes was nevertheless impressed by the scientific (and common-sense) evidence that mind and body do affect each other o A pin jabbed into the physical, “extended” finger is followed by a thought of pain in the “unextended” mind o Examining the evidence closely, he concluded that the mind is only aware of physical events in the brain Various motions can take place in the body without being followed by mental events, unless the physical motions first cause movements in the nervous system and then in the brain e.g. breathing, digestion Similarly, one can stimulate thoughts without affecting the body, just by producing certain physical motions in the brain e.g. the phenomenon of “ghost” limbs o All this led him to conclude there must be some point of contact between the mental and physical worlds, and that the contact must take place in the brain He believed this junction was found in the pineal gland at the base of the brain This belief doesn’t really answer the question how the mind and body interact in the pineal gland He became increasingly vague about the matter, and eventually said that, since we all experience the connection as fact, the question was best answered by not thinking about it, and just accepting it as one of those mysteries that can’t be comprehended The Materialist Theory: others weren’t prepared to give up so easily, and identified the initial separation of mind and body in Descartes’ thoughts as the key problem o if one refuses to grant that mind and body are 2 different kinds of being, one should have no trouble accounting for their interaction one way of avoiding Descartes’ pitfall is to adopt a completely materialist metaphysics and claim that both mental and physical events can be explained purely in terms of physical concepts and laws o Thomas Hobbes was the key advocate of this approach in Descartes’ day; some behavioural psychologists hold it today o The key idea is that what we call mental events are really (like physical events) only combinations of matter in motion The physical movements that occur in the brain are what we call thoughts, and these are produced by other events in the physical world, whether outside or bodies or within, and can in turn produce further physical motions in ourselves or outside ourselves Every idea is nothing but a set of physical occurrences in our higher nervous system and brain this has the advantage of being very simple o there is also a vast body of scientific evidence (psychology, psychiatry, physiology) about the physical basis of many mental events that makes it seem plausible e.g. treatments for depression, “brainwashing,” etc. work on “artificial intelligence” also suggests there may be some merit in this there are, however, some criticisms: o I am aware of sensations, emotions, thoughts – not physical occurrences in my brain; even if the latter cause the former, it still remains the case that they are different and distinguishable: hence, the mental world can’t be reduced merely to physical events o If mental events are all there is to it, how do you explain truth and error? How do you distinguish them, if they reduce merely to a series of physical events in someone’s brain? o I am forced into a determinist world view, with no room for free choice Further Thoughts on Mind-Body Dualism: (see text pp. 141-45) Descartes’ insistence that mind and body are 2 essentially different substances (“Substance Dualism”) leads to a problem that can be diagrammed like this: Subject (mental) Perception Object (physical) What happens here? How does one substance perceive a “completely different” kind of substance? Philosophers have (as usual) tended toward one extreme or the other, depending on which sort of skepticism they embrace: 1. Idealists (e.g. Descartes, Berkeley) are skeptical about whether we can trust that our perceptions fit reality, or whether there actually IS any reality outside our minds at all. Idealists think that the mental is all there is. This is a kind of solipsism: i.e. things have no independent existence outside of my thoughts about them. (“Subjectivism”). Descartes further believed that mind and matter are two completely different kinds of thing (“Substance Dualism”). 2. Materialists (e.g. Locke, Hobbes) are skeptical about whether the “mental” is anything other than the result of purely physical events in our brain. Materialists think that matter is all there is (“Monism”). This leads to determinism: i.e. there is no freedom; the world unfolds in a purely material/mechanical way. (includes “identity theorists,” “eliminative materialists,” and “functionalists”) Some philosophers have gone through extraordinary gymnastics to try to bring these extremes closer together. Epiphenominalists modify materialism and admit that our mental perceptions are more than physical states in our brain. However, they still judge them to be mere by-products of those physical states, as smoke is a by-product of fire. This still does not do our mental life justice. (“Identity theorists”) Occasionalists argue that, since the mental and physical can’t interact, what must happen is that, for each event in one realm, GOD makes a corresponding event occur in the other. The one event doesn’t cause the other; it is merely the occasion of God’s action. This still doesn’t answer the question of how the mental interacts with the physical (God takes the place of Descartes’ pineal gland), and makes for a “busy-every-minute” God who doesn’t have much in common with most conceptions of God. Monadists (e.g. Leibnitz) argue that everything, whether mental or physical, is independent and constitutes a monad whose actions are wholly determined by its nature, and not by its interactions with other monads. Monads only appear to interact in relationship because they have all been created by God in a “pre-established harmony,” so that, without influencing each other, events in each one nevertheless occur harmoniously with all of the others. While this gets around the problem of dualism, it is simply … incredible. Dual-aspect theorists (Spinoza – “the Monist’s solution”) reject dualism, and argue that the mental and physical are in fact “flip sides of a coin;” i.e. mind and body are both aspects of one and the same being. Therefore, whenever there is an event in one realm, there must be a parallel event in the other, since the mental and physical are just different ways of looking at the same thing. However, Spinoza identified the mental with God and the physical with nature; by arguing the two are just different aspects of the same thing, he in effect argued that nature is God (i.e. pantheism), which most philosophers and theologians find unacceptable.