Sociology 530 – Fall 2006

advertisement

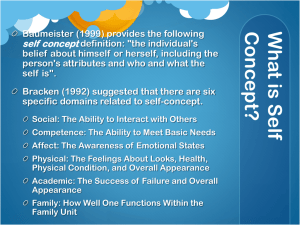

Sociology 319 – Spring 2009 Soc Perspectives on Social Psychology (Carr) Thursday February 12, 2009 Socialization (cont’d)/Self Socialization (Cont’d) 1. Bowles & Gintiss correspondence theory. This theory proposes that the educational system exists to meet the needs of the economy. As such, students are trained or socialized to be diligent and to follow orders. Additionally, not all children are given the opportunity to fulfill their potential; rather, children are tracked into classes or programs that will enable them to fill jobs that are needed by the economy. For instance, some children are tracked into “shop” or vocational classes because the economy needs both blue-collar and white-collar workers to function effectively. 2. The academic “tracks” that students are channeled into typically reflect their parents’ social class. This tracking, in turn, increases the chances that children will have educational and career trajectories that are very similar to their parents – thus perpetuating the existing social class structure. I. The Self A. What is it? 1. The self has two components: The I (active source) and me (the passive object). a. The self is the individual viewed as both the active source and passive object of reflexive behavior. The self emerges when we can act both as the subject (or person taking action, the I), or the object (the object toward which reflexive behavior is directed, the me). Human behavior is an interactive process between the I and the me. It is the process through which children learn to modify their own behavior. The Mead concept of self draws on the symbolic interactionism perspective. A central theme is that language and the ability to actively select and “make up” our roles are critical factors in the development of self. Our actions include both activity initiated by ourselves; and our reactions to ourselves - or our perceptions of how others will react to us. b. The “I” and the “me” evolve over time. self=I + me. The “me” or self as object emerges gradually among young children. 2. This two-part self cannot evolve until the following capacities are established: a. Language - For the self to develop, we must learn to use language to discern ourselves from others. b. Self-differentiation. People must be able to differentiate themselves from others. This ability develops by age 4-5. Children develop language skills and by learning that they have a name, they can eventually understand that they are an object, just as a book or table is an object. At the same time, children learn that their thoughts and feelings belong to themselves and thus they develop a sense of “I,” or the agentic active part of the self. (e.g., young children excessively referring to their own names). c. The ability to role-take. People must learn to see themselves and their own actions through the eyes of others. This is called the process of role taking. People imaginatively occupy the position of another person and try viewing the situation from that person’s perspective. Imagining others’ responses to the self, the child then learns how to view one’s self as object. For instance, by understanding how their bad behavior might be received by a parent, the child learns that he or she might be reprimanded and thus curbs the bad behavior before it starts. (“bad boy,” “bad girl.”) 3 The ability to role take is learned through two processes: play and game. a. Play: In the play stage, young children imitate the activities of people around them. Generally, they learn how to imitate the role of an individual, and they take on roles one at a time. They recreate complex behaviors performed as part of a selective role. Very often the model is a significant other, a person who has considerable influence on one’s self-evaluation and one’s acceptance of social norms. b. Game: As children mature, they then enter the game stage. Here, the games (or play activities) of children are more complex, and require that the child understand that fellow actors are involved, and one’s own behavior is molded by the actions of others. For instance, in order to play baseball, a child must understand the roles held by other players. Children learn how to imagine the viewpoints of people in different positions, how to coordinate with others, how to anticipate and react to the behavior of others, and how to follow social rules. The most common example of this is a sport, such as baseball or soccer, where the child must be aware of the possible actions of other players. All the players know what the responses associated with the other positions, and take these responses into account when devising their own behavior. In learning to adopt the views of others, children develop an understanding of the generalized other. I. A generalized other is a conception of the attitudes and expectations held in common by the members of the organized groups with whom one interacts. By knowing and understanding the generalized other, we learn to behave in compliance with “society” or what our extended social circle would say about our behavior. By this stage, children’s behavior is guided by an understanding of how others’ might react, and the rules and norms followed by others. B. Self-Concept 1. What is it? The self-concept is the organized structure of cognitions or thoughts that we have about ourselves. Our self-concept includes many different components, or identities. Our self-concepts are very important. Whether we feel positively or negatively about ourselves, and the types of behaviors and social settings we choose for ourselves are often molded by our selfconcepts. a. Measuring self-concept. We might use the Twenty Statements Test. Here, people simply right down 20 different responses to the question of “Who am I?” b. Our self-concepts - or how we describe ourselves - often have social roots. How we view ourselves is often a product of our interactions with others. 2. Looking glass self (Cooley 1902) Our self-concepts are often the product of social interaction with others. This is an instance of reflexive behavior, where children look at their own behavior “from the point of view of other people.” According to Cooley, the self is modified by the feedback we receive from others. Specifically, how we view our self is based on our PERCEPTIONS of how others see us. This feedback is not an objective reality that we can grasp directly. Rather, we must interpret others’ responses to us. a. The looking-glass self has three parts: (1) how we think we appear to others; (2) how we think they judge what they see; and (3) how we feel about these [perceived] judgments. II. Identities A. Definition: Identities are the categories people use to specify who they are and to locate themselves relative to other people. B. Types of identities 1. Role identity: This is an aspect of our identity that depends on the social position we hold in society. Role identities might include family, gender, occupational, or agebased roles. One’s membership in a group (e.g., voluntary, religious, race/ethnic) might also be considered role identities. These identities are quite flexible, in accordance with the symbolic interactionist approach to understanding roles. Exactly how a person enacts a role identity depends on individual tastes, context, and on the other people with whom one is interacting. 2. Personal qualities: These aspects of self-concept might include personality or physical characteristics. Personal qualities also refer to one’s style of interpersonal behavior, such as shy or outgoing. They might also provide augmentations of role identities (e.g., an assertive woman, mature teenagers . . .) 3. Self-evaluations. These types of self-descriptions are like personal qualities, yet they take on a more judgmental or evaluative tone. (e.g., smart, moral, etc.). III. Enacting Identities - Individuals hold a variety of identities, but we vary in how important each identity is, and in terms of when and where we invoke each aspect of our identity. Our identities also impact our day to day experiences; our behaviors, attitudes, and emotions are impacted by our identities. A. Situated self: How we describe ourselves might vary over time and place. However, we tend to focus on aspects of our selves when those aspects differentiate us from others. This is what is called the situated self. The situated self is the subset of self-concepts chosen from our identities, qualities, and self-evaluations that constitutes the self we know in a particular situation. An identity is most likely to be invoked or enacted when that aspect of self is unique to the current context. For example, few undergraduates would mention “20-year-old” as one of their identities. However, perhaps older students returning to college after several years of work might mention their age as an aspect of their identity. B. Salience Hierarchy 1. The various identities we hold are arranged in a hierarchy according to their salience, or their relative importance to our self-concept. The degree to which one of our identities impacts our behavior and attitudes is determined, in part, by the salience of that identity. There are four general ways that the salience of an identity impacts our behaviors. a. The more salient, or important, an identity is to us, the more likely we are to perform activities that express that identity. (e.g., a person who names “politically activist” as a highly salient identity will be more likely than others to engage in political protests and letterwriting campaigns). b. We are also more likely to view most situations as an appropriate venue for enacting an identity if that identity is very important to us. (e.g., a political activist might view most social encounters as an appropriate time to discuss politics). c. We will actively seek out settings where we can enact those identities that are important to us. (e.g., a political activist will be more likely to attend “social issues” forums in the dorms of other events where political issues are discussed). 2. What makes an identity salient/important? a. The resources (e.g., time, money, and effort) we have invested in constructing the identity. b. The extrinsic rewards that such as a role has delivered c. The amount of self-esteem staked on enacting the identity well. Self-Esteem A. What is it? 1. Self-esteem is one’s attitude toward one’s self, or one’s overall evaluation of one’s self. Self-esteem can be domain-specific, meaning we have feelings about ourselves in different areas, such as academic aptitude, physical attractiveness, athletic ability, etc. Our overall selfesteem is considered the product of these individual evaluations. However, our overall selfesteem is affected most heavily by self-esteem evaluations in the domain that is most important or salient to us. B. Social Class Differences in Self-Esteem (Rosenberg and Pearlin study) 1. Children. No association was found between social class and self-esteem. 2. Adolescents. A modest or weak association was found, 3. Adults. A moderate/strong association was found C. What explanations are given for these observed relationships? 1. Social comparison theory (Leon Festinger) a. This theory holds that people have a constant desire or drive to assess or evaluate themselves, their abilities, and their opinions. In most life domains, there is not an objective standard, so we evaluate ourselves by comparing ourselves with others. Rosenberg & Pearlin believe that younger children view their peers as being of a similar social class, thus children are unlikely to view themselves as “worse off” than their classmates. This could be either perception or fact, given that most elementary schools serve homogeneous, small neighborhoods. Children also have limited knowledge and awareness of social class. i. For adults, in contrast, many social interactions occur with members of other social classes. Although jobs within the workplace are stratified, most workers are wellaware of their place in their social class structure. 2. Reflected appraisals (Cooley) a. This theory states that we see ourselves as we perceive others see us. We can never have complete knowledge of what others think of us; all we have to go on are our perceptions. Each person has a role set, or a group of persons with whom he interacts. Whereas the adult’s role set consists of status unequals, almost all of the individuals who constitute the child’s role set are of his/her social class. Although the child may be evaluated by others, it is seldom due to social class. Moreover, parental perceptions are an important part of children’s self-esteem, under the reflected appraisals framework. Parents are not likely to assess their children on the basis of social class. To the contrary, a spouse or child may judge a parent based on his or her economic success. 3. Self-perception theory (Bem) a. This theory argues that we come to know ourselves not by introspection, but simply by observing our own behavior. We observe and interpret our own behaviors. Our selfassessments are often based on our own behavioral outcomes. b. How does this pertain to social class? For children, social class is ascribed. That is, they are born into a social class; they do not “work” to achieve it. For adults, however, social class is achieved; that is, their social class is the outcome of their own efforts and actions. Thus, when adults examine their own behavior, such as their social class, they may interpret their behavioral outcome (i.e., social class position) as a reflection of their own ability, efforts, and skills. Those who observe themselves as holding lower-class jobs, may then draw the conclusion that “I am not capable,” or “I am not a hard worker.” 4. Psychological centrality/salience a. This concept refers to how important something is to us, or how “central” it is to our overall identity. Some aspects of our identity are more important to self-esteem than others. If you’re an awful athlete, but don’t highly value athletic ability, or view this as relatively unimportant given your other attributes, then your self-esteem shouldn’t suffer (much) if you are evaluated negatively in terms of athletic ability. b. Rosenberg & Pearlin believe that social class is much more important to, or central to, the identities of adults rather than children. One reason is that adult social class is achieved, yet children’s social class is ascribed. Even among adults, for those who reported on surveys that income was very important to them, the effects of social class on self-esteem were amplified. 5. Self-discrepancy theory a. Higgins argues that the self-concept has three components, and that mismatches between these aspects of the self-concept can be distressing. i. Actual self: Who we are. ii. Ought self: Who we believe we should be. iii. Ideal self: Who we would like to be. b. The “ought” and “ideal” do not necessarily overlap, although they often do. The “ought” reflects cultural messages of what we “should” do, whereas the “ideal” is what we want for ourselves. However, the latter often is informed by the former. c. Mismatch of actual & ought guilt, tension, fear d. Mismatch of actual & ideal sadness, depression, low self-esteem 6. Possible selves a. Markus and Nurius argue that the self-concept comprises views of one’s self in the future, including: i. what one would like to be ii. what one might be iii. what one is afraid of becoming b. Discrepancies between current and future self can affect behavior, motivation, mood. As such, persons who are dissatisfied with current aspects of the self may be motivated to make positive changes and improvements in their life.