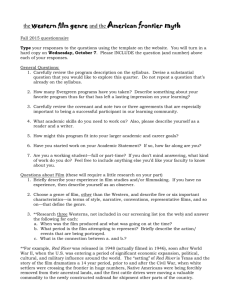

電影研究概論 941002017邱靖雅 Binary Opposition Most films would

advertisement

電影研究概論 941002017 邱靖雅 Binary Opposition Most films would start by setting up the lines of conflicts to constitute events and actions of the story. Binary opposition is the way which used very often. Always the opposition can not be resolved unless one or the other side withdraws or surrender. And the hero usually operates as someone who can understand both sides of the pattern; he is usually strong and dangerous. Take the classic of western film, Shane (1953) for example, it provided a simple system in which viewers can easily differentiate good from bad through the determining category of the good hero. Especially in this film, it took the viewpoint from the Joey child, who see Shane as a hero and admire him very much. Shane has a rough past as a gunslinger but eventually proved his goodness to Joe and other homesteaders by helping them against Ryker and his gunslingers who tried to push away homesteaders out of the valley. See the basic set of oppositions in “Shane”: Homesteaders Domestic Helpless Weak Submissive Gunslingers Wild Dangerous Strong Aggressive This is the situation between Joe the homesteaders and Ryker the gunslingers before Shane came to the homesteaders’ aid. As tensions mount between the two factions, the cattle baron Ryker hires Jack Wilson, a cold-blooded and skilled gunslinger. Shane was finally forced to take on Wilson in a climatic showdown, killing him and Ryker. In binary opposition, the good (Shane and Joe) always win, particularly in western films. Structuralism Structuralism has been very powerful in its influence on narrative theory. The narrative always has a particular pattern, a structure. The previous introduction about binary opposition is one kind of forms which has been applied in films very often. Except for binary opposition, an alterative way of explaining the structure of narrative is to look at it as a process. Always the narrative begins in a stable point of equilibrium, a state of plenitude; things are satisfactory, peaceful, calm, or recognizably normal. This equilibrium is then disrupted by some force which results in a state of disequilibrium. This state can only be resolved through the action of a force directed against the disrupting force. The result is the restoration of equilibrium or plentitude. “The Magnificent Seven” (1960) is a good example, near the beginning a gang of bandits killed a man and rob food of the Mexican village, warning the villagers they would come back for more food. The peace of that small village no longer exists unless they find a way to fight back. With the help of seven gunslingers and some sacrifice, the villagers finally get their peace back. It may not be entirely circular but it returns to the equilibrium to a certain extent. We can apply this to “Shane”; homesteaders live peaceful at first yet disrupted by bully cattle baron who wants to push them away, after showdown and bloody the homesteaders eventually came to the end with peace through Shane’s help. It is easy to chart because most films allows their disruptions to occur near the beginning. Codes and Conventions Our understanding of codes and conventions of films has a lot to do with how we had been educated and our learning about our and other societies. At the most elementary level we understand the societies depicted in films through our experience of our own society. As we watch a film and understand it, we look at gestures, listen to accents, or scan a style of dress in order to place characters within a particular class or culture. And if the gestures, accents, and styles are not those of our society, we understand them through our knowledge about the society in the film. All of these clues are codes- systems by which signs are organized and accepted within a culture. If we watch western films, we must learn the cowboy culture and know the spirit it expressed. Conventions are like codes, they are systems which we all agree to use. So when we see Shane and the Starrett family get on a carriage in one shot, and in the next they has arrived the town, we know that this is a convention, a shorthand method for getting characters from A to B without screen time. It is conventional that films are only realistic within certain unspoken limits; they are not try to imitate the full complexity of life if is unnecessary. Conventions have built up around the representation of the female in films. The conventions of “halo” and “soft-focus” effects though defying reality, they are widely accepted in representation of women; Hollywood film has turned the female form into a spectacle, an exhibit to be scanned and arguably possessed by the male viewer. It is never easy to challenge or disregard existing conventions. Films need their shorthand, their accustomed routes to operate effectively. But I think that “Casablanca” (1942) may have broken the convention. The lover of the leading character is a married woman and her husband is not him, and the end of the film, the couple did not live together happily hereafter, but love remains in their mind, he accomplished her marriage. At least it’s not a conventional end of a romantic film. However, once the convention was broken, it might be another convention. Genre One of the ways in which we distinguish different kinds of film narratives is through genre. In film, genre is a system of codes, conventions, and visual styles which enables an audience to determine rapidly and with some complexity the kind of narrative they are viewing. Genre is the product of at least three groups of forces: the industry and its productions practices; the audience and their expectations and competencies; and the film text in its contribution to the genre as a whole. Yet it is easy to make genre a deterministic threat to creativity. For the industry, there is often enormous market pressure to repeat successful versions of genres and produced with an eye on the conventional limits of the genre. For the audience, genre is one of the determinants of the audience’s choices of a film, not only in terms of whether they possess the competencies to appreciate that genre, but in terms of what kind of film it is they want to see, and whether the specific example of film suits the taste. For example, when a couple go to the movie theater, the man may want to see “Shane” because he is an enthusiast of western films while the woman prefer to see “Casablanca” for she fond of romantic film.