Orwell on British Antisemitism

advertisement

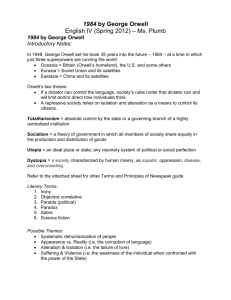

The Timeliness of George Orwell ©Joel Fishman, Ph. D. On June 25, we will commemorate the centenary of the birth of one of the most creative authors of the twentieth century. Eric Blair, who adopted the pen name George Orwell, was born in Motihari, Bengal, India in 1903 and received his education at Eton.1 He lived a relatively brief life (25 June 1903 -21 January 1950) with ups and downs. (Orwell who was a chain smoker lived with and died of tuberculosis). He is known for his two great classics which reveal the ugly face of totalitarianism. Animal Farm, published in London on 17 August 1945, an allegory which portrays communist society in Soviet Russia originally was presented as a “Fairie Tale.” Nineteen Eighty-four, published in London in June 1949, gives a chilling look at the workings of totalitarian society as it might exist anywhere. The drama of Nineteen Eightyfour is set in England for the express purpose of demonstrating how a totalitarian regime and society could be constructed even in a country with a centuries-long liberal tradition.2 The choice of an English setting lends the plot and characters a horrifying air of credibility – the essence of the “Orwellian” moment. Although these famous novels portray fictional societies, they have a sufficient sense of For his autobiographical statement, see, “Author’s Preface to the Ukranian Edition of Animal Farm,” George Orwell, The Collected Essays, vol. 3, As I Please, 1943-1945, eds. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1970): 455 ff. 2 Ibid., 4: 564. 1 2 immediacy as to leave a searing impression on the reader’s mind. Orwell was an accomplished essayist on all manner of subjects and created a rich corpus of non-fiction writing, which reflects a fine analytical mind, concern for the truth, and dislike of totalitarianism (at that time embodied in Stalin’s communism and German Fascism). His many interests included family life, social mores, women’s fashion, and food. An excellent observer, he was relentless in his efforts to discover the essence of a problem or detect the implications of certain ways of thinking. Orwell also possessed a well- developed sense of fairness, decency, and compassion. During the early stages of his career, he experienced the painful deprivations of extreme poverty. One need only read such autobiographical statements as Down and Out in Paris and London (London, 1933), or his essay describing Paris of the ‘thirties, “How the Poor Die.”3 A socialist with an acute sense of social justice, he joined the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), as did many committed young men and women of his generation. Unlike many English writers of his day, Orwell took notice of Jews, who were part of his world. He devoted careful attention to antisemitism, particularly in English society and briefly mentioned Zionism in his essay, “Notes on Nationalism” (May 1945)4, which he 3 4 “How the Poor Die,” The Orwell Reader (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1956): 86-95. Collected Essays 3: 410-431. 3 placed in the category of “Positive nationalism.” However, he did not go as far as his contemporary, the socialist Richard Crossman (1907-1974) who visited the postwar D.P. camps and called for more certificates for Holocaust survivors to enter Mandatory Palestine.5 Orwell worked mainly with two Jewish publishers. The first was Victor Gollanz (1893-1967) who managed the “Left Book Club” but did not accept Animal Farm. Turned down by three publishers, Orwell eventually placed his manuscript with Secker & Warburg. From the correspondence, it is evident that he subsequently developed a relationship with Fred Warburg based on appreciation and respect. He praised Warburg’s courage in publishing Animal Farm, which put his firm at risk.6 Later, Secker and Warburg brought out Orwell’s Collected Essays in four volumes with an index and explanatory footnotes which enable the reader to locate and identify ideas, subjects, and personalities quickly and easily. During the Second World War, Orwell worked for the Indian Service of the B. B. C. and wrote regularly for the press. He identified several important issues and themes that characterized life in the twentieth century and transcended the circumstances of the moment. In this respect, Orwell resembles the nineteenth-century historian, Alexis de Tocqueville. Both devoted careful thought 5 6 Palestine Mission a Personal Record (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1946). Letters to Victor Gollanz, 14 March 1947 and 25 March 1947, ibid., 4:353-356. 4 attention to the workings of democracy. Like Tocqueville, he was aware of the fact that the modern totalitarian state could develop better and more efficient means of suppressing individual freedoms than in earlier periods of history. [See Appendix I] Therefore, Orwell fought for the preservation of freedom and safeguarding of democratic society. Whereas Tocqueville had foreseen the dangers of totalitarianism, Orwell dealt with them as a contemporary. ….By comparison with that existing today, all tyrannies of the past were halfhearted and inefficient. The ruling groups were always infected to some extent by liberal ideas, and were content to leave loose ends everywhere, to regard only the overt act and to be uninterested in what their subjects were thinking. Even the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages was tolerant by modern standards. Part of the reason for this was that in the past no government had the power to keep its citizens under constant surveillance….7 He was sensitive not only to the real threat of totalitarianism, then on England’s doorstep, but also to its destructive effects on freedom of thought. He opposed ideological thinking and was committed to the application of reason to the human condition. For the Jewish readers in Israel and the Diaspora, the following subjects which Orwell treated are timely and relevant today: his analysis of anti-Semitism in English society; the influence of totalitarian thought on society as manifested particularly in ideological thinking; the 7 Nineteen Eighty-four (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1964): 165. 5 rewriting and falsification of history, and the condition (described in Nineteen Eighty-four) as “War is Peace.” Orwell on British Antisemitism The common observation that George Orwell’s attitudes toward the Jews reflected the prejudices of his class appears somewhat simplistic. In February 1945, Orwell wrote an informative essay entitled, “Antisemitism in Britain,” for the American journal, the Contemporary Jewish Record (April 1945), now known as Commentary. He wrote that antisemitism existed in Britain, but it was considered bad manners to express such feelings openly, because of the Nazi persecutions of Jews. He considered antisemitism an irrational sentiment which required honest study and frank soul-searching. In a separate essay, “England your England”, he referred to England’s “worldfamed hypocrisy,”8 evident in his description of an “Intercession Service” for Polish Jewry which took place in a synagogue in St. John’s Wood in 1943: … there is widespread awareness of the prevalence of anti-Semitic feeling, and unwillingness to admit sharing it. Among educated people, antisemitism is held to be an unforgivable sin and in a quite different category from other kinds of racial prejudice. People will go to remarkable lengths to demonstrate that they are not antisemitic. Thus, in 1943 an intercession service on behalf of the Polish Jews was held in a synagogue in St. “England your England,” in George Orwell, Selected Essays (Harmondsworth: Penguin and Secker & Warburg, 1957): 66. 8 6 John’s Wood. The local authorities declared themselves anxious to participate in it, and the service was attended by the mayor of the borough in his robes and chain, by representatives of all the churches, and by detachments of the R.A.F., Home Guards, nurses, Boy Scouts and what-not. On the surface it was a touching demonstration of solidarity with the suffering Jews. But it was essentially a conscious effort to behave decently by people whose subjective feelings must in many cases have been very different. That quarter of London is partly Jewish, antisemitism is rife there, and, as I know well, some of the men sitting round me in the synagogue were tinged by it. Indeed, the commander of my own platoon of Home Guards, who had been especially keen beforehand that we should ‘make a good show’ at the intercession service, was an ex-member of Mosely’s Blackshirts. While this division of feeling exists, tolerance of mass violence against Jews, or, what is more important, antisemitic legislation, are not possible in England. It is not at present possible, indeed, that antisemitism should become respectable. But this is less of an advantage than it might appear.9 The Power of Holding Two Contradictory Beliefs in One’s Mind Simultaneously Orwell also devoted attention to the harmful effect of ideological thinking, particularly on the perception of reality. In his sharp critique of leftist English intellectuals who propagated pro-Soviet ideological thought, he remarked: “They can swallow totalitarianism because they have no experience with anything except liberalism…. So much left-wing thought is a kind of playing with fire by people who don’t even know that 9 Collected Essays, 3: 381-382. He also described the Jews of Marrakech in the Spring of 1939, ibid., 1:428-429. 7 fire is hot.”10 And, in his well-known essay, “Notes on Nationalism” (May 1945), Orwell noted that such thinking reflected flagrant dishonesty, an inability to discuss certain topics rationally and a disregard of reality. His outstanding analysis of pacifism has a particularly modern feel, because even at this early stage, Orwell detected its anti-western prejudice and inherent double standard: …. There is minority of intellectual pacifists whose real though unadmitted motive appears to be a hatred of western democracy and admiration of totalitarianism. Pacifist propaganda usually boils down to saying that one side is as bad as the other, but if one looks closely at the writings of the younger intellectual pacifists, one finds that they do not by any means express impartial disapproval but are directed almost entirely against Britain and the United States. Moreover, they do not as a rule condemn violence as such, but only violence used in defense of western countries.11 In addition, Orwell often invented creative and accurate expressions for complex ideas and concepts. For example, in Nineteen-eighty- four, he coined the term, “Doublethink,” namely, “the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one’s mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.” In “Notes on Nationalism,” Orwell redefined “Nationalism,” as a blind commitment to an ideology, to be distinguished from “patriotism”: “The abiding purpose of every nationalist is to secure more power and more prestige, not for himself but 10 11 Selected Essays, 36,37. “Notes on Nationalism,”(May 1945) Collected Essays 3:424-425. 8 for the nation or other unit in which he has chosen to sink his own individuality,”….12 According to that definition, Nationalism included such movements and tendencies as Communism, political Catholicism, Zionism, Antisemitism, Trotskyism, and Pacifism. Who Controls the Past Controls the Future Orwell observed that totalitarian regimes by nature must engage in “organized lying13 and that the falsification of history was essential for maintaining total power. Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth. The friends of totalitarianism in this country tend to argue that since absolute truth is not attainable, a big lie is no worse than a little lie. It is pointed out that all historical records are biased and inaccurate, or, on the other hand, that modern physics has proved that what seems to us the real world is an illusion, so that to believe in the evidence of one’s senses is simply vulgar philistinism. …. Already there are countless people who would think it scandalous to falsify a scientific text book, but would see nothing wrong in falsifying an historical fact. It is at the point where literature and politics cross that totalitarianism exerts its greatest pressure on the intellectual….14 His famous statement with regard to the fabrication of history comes from Nineteen Eightyfour, whose main character, Winston Smith, worked full time for the party falsifying the records of 12 Ibid., 3: 410-431. Ibid. 14 Ibid., 4:86. 13 9 the past. From this novel comes the famous slogan: “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”15 The significance of falsification of history is explained in this novel, which should be considered a political model of what life under a totalitarian regime, when drawn to its logical conclusion. This is noteworthy, because in our own experience, in Israel and abroad, a group of “New Historians” have seized upon history as a weapon, rewriting (and fabricating) the history of Zionism for the purpose of bringing it into discredit.16 According to Orwell’s interpretation, the motive for such efforts could only be explained a drive to seize intellectual hegemony (as an initial step) over Israeli society, by undermining the historical legitimacy of the Jewish State, an act of cultural aggression whose full significance is yet to be fully appreciated. Peace is War Another observation about contemporary life is the dictum, “Peace is War,” one of his famous contradictions. In the past, war resulted in decisive victories, bringing rewards to the victor and losses to the vanquished, which kept people in close contact with reality. He observed, however, that war, by becoming continuous had ceased to exist. However, in a situation of closely matched 15 Nineteen Eighty-four, 199. In his well-known book, The Jewish State, Yoram Hazony has described this process extensively. Yoram Hazony The Jewish State (New York: Basic Books, 2000): 40-46 16 10 power relationships, war may “continue everlastingly and without victory.”17 Meanwhile the fact that there is no danger of conquest makes possible the denial of reality which is the special feature of Ingsoc [short for the English Socialist Party, the ruling party of Oceania] and its rival systems of the thought. Here, it is necessary to repeat that what has been said earlier, that by becoming continuous war has fundamentally changed its character.18 When war becomes continuous, it makes the perception and understanding of objective external reality less immediate. When prolonged, such a state of affairs makes it easier for a governing class to control the people. He observed that the demands of war could be used for keeping the structure of society intact, and maintaining a state of war was associated with holding power: Reality only exerts its pressure through the needs of everyday life – the need to eat and drink, to get shelter and clothing, to avoid swallowing poison or stepping out of top storey windows and the like… Cut off from contact with the outer world, and with the past, the citizen of Oceania is like a man in interstellar space, who has no way of knowing which way is up or down. The rulers of such a state are absolute, as the Pharaohs or the Caesars could not be. They are obliged to prevent their followers from starving to death in numbers large enough to be inconvenient, and they are obliged to remain at the same low level of military technique as their rivals; but once that minimum is achieved, they can twist reality into whatever shape they choose.19 It is no secret that for some time Israel has been in a condition of nearly permanent low- 17 Ninety Eighty-four, 160. Ibid. 19 Ibid., 160. 18 11 intensity war and has entered the condition of “war is peace” (and vice versa). The government may not have the power of the Pharaohs or the Caesars over its citizens, but the number of those who experience hunger and resort to the soup kitchens is constantly rising. Further, certain politicians and intellectuals are trying to convince the public to accept propositions which have no basis in reality. Frequently, news reports indicate that many Israeli authors and politicians deny reality and reject empirical evidence, making decisions and advancing positions fully out of touch with external reality. Such patterns of behavior have led to two cases of Ta’uth be-Conceptsia (perception failure), one acknowledged (the Yom Kippur War, 1973) and the other denied (Oslo, 1993). Although we are not yet able to take full account of Orwell’s lessons, as applied to Israel, several “Orwellian” manifestations may clearly be identified. For Orwell, totalitarianism represents a danger to the entire free world and continuously must be confronted. It would be a mistake to assume when confronting its challenge that things will turn out for the best, of their own accord.20 On the occasion of the centenary of his birth, Orwell’s message continues to be timely and relevant. --------------------------------------- Appendix I: David Ben Gurion on Totalitarianism: In his Survey, delivered to the Zionist Conference in London at the beginning of August 1945, Ben 20 Ibid., 2: 297. 12 Gurion spoke out about the danger of totalitarianism, particularly in Stalinist Russia: But there are additional dynamic factors which, unless counteracted, must have an insidious effect on the course of Jewish history and may even lead to the complete decay of world Jewry. One of these dynamic factors which may interrupt the existence of the Jewish nation is the increased power of the State over the individual. The current tendency is for States to secure complete control over the lives of their people, intellectually and morally, as well as economically, and such trends are likely to have disastrous consequences on a weakened and reduced Jewry. The Jewish people had struggled and suffered throughout the ages and had resisted being swallowed up, but in the recent time of closely organised States, the Jewish people, … may not be able to continue resistance. This absorption of the individual by the State, whether it be good or bad for the peoples of their respective countries living in their own land, may lead ultimately to the complete extinction of the Jewish people outside Palestine. 21 21 “Ben Gurion’s Survey,” The New Judaea 21:11/12 (August-September, 1945): 173.