A Cultural Sensitive Framework for Understanding

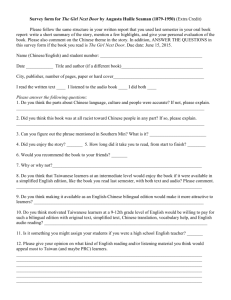

advertisement

Word count: 7,100 A Cultural Sensitive Framework for Understanding Knowledge Workers from a Non-Western Background Author: Tan, Po Li (po_li.tan@kcl.ac.uk) (Author to correspond with) Tel : +4402078483115 Fax: +4402078483252 The Learning Institute King’s College London James Clerk Maxwell Building Waterloo Campus 57, Waterloo Road London SE1 8WA, UK A Cultural Sensitive Framework for Understanding Knowledge Workers from a Non-Western Background Abstract: The significant link between learning and knowledge economy is so crucial that the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development has reconceptualised the term knowledge-economy to call it ‘learning economy’. One of the main challenges of human resource development in the ‘learning economy’ is to evaluate the learning attributes of the knowledge workers. There is an abundance of literature on learning but many do not go beyond classroom learning. The Students Approaches to Learning provides a relevant basis for adult learning investigation but studies have reported its lack of consideration for cross-cultural issues. Thus, theoretical underpinnings of cultural values were used to address the gap. Two adapted instruments which considered both etic and emic characteristics were administered on 959 Malay and Chinese knowledge workers to ensure conceptual equivalence. The consideration of cultural variables in the investigation unveils indigenous learning constructs such as ‘Memorising and Understanding’ and ‘Face’. The inclusions of ‘emic’ concepts ensure a rigorous framework in understanding adult learners from a non-Western background. Keywords: Human Resource Training, Knowledge Workers, Adult Learning, CrossCultural Methodology, Psychometrics Testing. 2 A Cultural Sensitive Framework for Understanding Knowledge Workers from a Non-Western Background (6805 words) The global scene The significant link between learning and knowledge economy is so crucial that the Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) (2001) has reconceptualised the term knowledge-economy to call it ‘learning economy’ (Falk and Smith 2002). Employment in the knowledge-based economy is now characterized by the increasing demand for multi-skilled workers; independent and critical thinkers who can use knowledge as a commodity to survive in the intensified and competitive global scene (Drucker 1999; Robinson 2001). When working for Shell, de Geus studied the common characteristics of the world’s most enduring corporations, and concluded that these surviving corporations are similar to individual human beings. Two key characteristic of knowledge workers that can have significant impact on corporate survival are “an ability to learn and adapt”, and “an awareness of the changing environment” (Stephenson 1999). This intense focus on the importance to learn and adapt inevitably calls for a new demand on for the knowledge-workers to consider learning as part of their daily work. In light of the above, one of the main challenges for human resource development in the 21st century is to evaluate human capital, how to measure the 3 learning attributes or learning values1 of people relevant for knowledge economy.— whether the ‘learning values’ practised by the knowledge workers would enhance their ‘approaches to leaning’ in order to survive the changes in the competitive global market. The study is set in Malaysia—a developing nation. Malaysia’s Vision 2020 is the government’s long term plan to navigate the country to become a fully developed country, capable of competing in the global knowledge economy. Given that Malaysia is a multicultural country where the majority of the population is made up of the Malays and Chinese, it is crucial to understand and appreciate the different learning values that may exist between the two ethnic groups and how they may lean from each other to support the Malaysian Government vision 2020. However, studies involving learners from a non-Western culture would be challenged as most learning models such as Jarvis learning model (Jarvis 2006), Kolb’s theory of learning (Kolb 1976), Biggs 3P model (Biggs 1987a), and Novak’s meaningful learning model (Novak 1998) are developed from the Western perspective. Whilst these theories emphasised that cultural issues are critical in understanding learning, none of these theories include the concept ‘culture’ in their models. In fact, cross-cultural researchers such as Watkins (2000) argues that many theories emerged from the Western perspectives may not be appropriate to nonWestern cultures and concludes that most of the major theories being described and tested such as Kohlberg’s theory of moral development, Piaget’s theory of cognitive 1 Learning values refer to values which have direct link to enhancing the quality of learning outcomes such as ‘being persistent’, ‘able to bear hardship’, and ‘to value the pursuit of education’. Values which may indirectly impact on learning such as ‘kindness’, ‘patriotism’ are not considered in the current study 4 development, Maslow’s theory of self actualisation, and Herzberg’s theory of job satisfaction are based on the values of the Western culture in particular an individualistic, independent conception of the person. Underpinned by the above intent and argument is the challenge of developing a culturally sensitive framework for the investigation. Hence, the purpose of the study is to develop a culturally sensitive framework to investigate knowledge workers from a non-Western background, with Malaysian adult learners as the exemplary context. Investigation of Asian adult learners and Biggs’ 3P Model Any attempt to study Malaysian adult learners’ approaches to learning is confronted with two issues. Firstly, there is a lack of understanding of specific learning theories which focus on the process of adult learning in the formal institutions (Merriam 2001)—a preferred mode of professional development programme in Malaysia (Tan 2006). Secondly, although adult learning theories examine workplace culture (Billett 2001) or organizational culture (Brown, Collins, and Duguid 1989), little is known about the influence of personal or cultural impacts on adult learners (Merriam and Caffarella 1999). What seems to be downplayed is the kind of values which can enhance or even inhibit learning processes. Hence, investigation of Malaysian adult learning needs to take a rather different perspective to that of current adult learning theories that emerged in the West. Merriam and Caffarella (1999) have frequently appealed to researchers to consider the complexity of the adult learning process by using a more holistic and 5 comprehensive approach. Biggs’ 3P Model 2,emerged from a focus on students’ approaches to learning, captures the strength of the whole learning system by arguing that teaching and learning are intertwined, where student factors, teaching context, ontask approaches to learning and the learning outcome are mutually dependent and form a dynamic system (Biggs 2001). Biggs’ model highlights the functional relationships of what he calls the 3Ps of Presage, Process and Product Factors. The Presage Factors include variables such as values, and past learning experiences, variables which are pertinent for the examination of adult learners. The second factors which he calls Process Factors include learning strategies such as problem solving, mentoring, and project work. The final factor in Biggs’ 3P Model is the Product Factors which consist of learning outcome variables. The three Factors form a total system in which an educational event is located. Such a systemic approach can be relevant for the investigation of adult learners, when considered carefully. The Study Process Questionnaire (SPQ) and its limitations for adult learners from a non-western context Based on the theoretical underpinnings of the 3P Model, Biggs developed the Study Process Questionnaire (SPQ) (Biggs 1987b) and the Revised-Study Process Questionnaire-Two Factor (R-SPQ-2F) (Biggs, Kember, and Leung 2001) to assess students’ approaches to learning in the formal settings. In R-SPQ-2F, Biggs, Kember and Leung (2001) operationalised two concepts of ‘Deep’, and ‘Surface’ to form a motive/strategy combination. The combination of the motive/strategy index may indicate learners’ general ‘approaches to learning’ which, according to Biggs (1987b), are relatively stable and do not change overnight. 2 Though it is not designed specifically for adult learners 6 There are, however two issues with regard to SPQ or R-SPQ-2F used on Asian adult learners that need to be considered. Firstly, most of the studies, which have adopted the SPQ, have targeted full time students moving directly from secondary schools into university undergraduates programmes. This group of students may display different motives and possibly have less implicit knowledge in their Presage Factor than adult learners. The exploration of the literature indicates there is little research data on adult learners, who being adults, would have more life and work experiences, than the typical ‘school-leaver’ full time undergraduate university learners (Pillay, Boulton-Lewis, Wilss, and Rhodes 2003; Richardson 1995). Secondly, approaches to learning displayed by adult learners measured by the SPQ appear to reflect only general motives in the Presage Factors (i.e. Surface or Deep Motives) to learn. They do not reflect explicitly how these motives may be related to cultural variation which may influence motives in the Presage Factor. These are critical variables in the investigation of different cultural groups in Malaysia. One of the essentially acknowledged criticisms of the SPQ is that it has not been designed to capture cultural variables (Kember, Wong, and Leung 1999). Since personal dispositions such as cultural values are recognised to be a significant variable when researching adult learning (Merriam and Caffarella 1999), and that SPQ is limited in its capacity to deal with this, there is a need to either improve SPQ’s capacity in this regard or use another instrument that may throw light on the values variable and thereby complement SPQ’s findings. Hence, the current study attempts to adapt SPQ to be sensitive to the Malaysian adult learners’ context and also to compliment a learning value survey, with the intention of providing a holistic framework for the investigation of Malaysian adult learners. 7 Study on values Considering the criticism of SPQ, literature on ‘values’ was examined. A literature search on values reveals that value studies have broadly gone in two directions. One direction, which is taken from the social psychology or the management perspectives, investigating more standardised and consistent universal or organizational values (See Hofstede 1991; Schwartz and Sagie 2000). The other direction is often taken by educational psychologists, examining for instance, Confucian values3 and learning (See Stevenson and Lee 1990; Tweed and Lehman 2002). However, Chen, Stevenson, Hayward, and Burgess (1995) have criticised the latter, arguing that whilst there have been attempts at investigating the relationships between learning and specific cultural issues, investigation of cultural values and learning on a broader perspective and with a more standardised evaluation, has not been well documented. Interestingly, a synthesis of literature from the two perspectives found that they both harmonize as evident in Table 1, column 1 and 2. For instance, studies on learners from Confucian backgrounds found that they, besides having a strong belief of effort and human malleability (Lau and Chan 2001), place very high importance on learning or education (Li 2001). In addition, they also practise pragmatic learning more than their Western counterparts (Volet, Renshaw, and Tietzel 1994) and there is significant influence from the social in-groups such as family and peer members (Sijuwade 2001). These findings complement the value items developed by social psychologists for Asians in general. Table 1 provides evidence that the two surveys—Culture Value Survey (CVS) (Chinese Culture 3 Confucian values are chosen in this study as they provide strong theoretical framework and they are akin to Malaysian values (Hussin, 1997) 8 Connection 1987) and Chinese Culture Values Survey (CCVs) (Fan 2000) can be categorised to complement with the findings from the educational psychology discipline. (Insert Table 1 here) For this study, R-SPQ-2FM (Revised-Study Process Questionnaire-2 Factors Malaysia—the adapted version of Study Process Questionnaire and Revised-Study Process Questionnaire-2 Factors) and LVS (Learning Values Survey—the adapted version of Chinese Value Survey and Chinese Culture Values) when used simultaneously provides indigenous insights into the design of a culturally sensitive framework for the investigation of Malaysian adult learners in the professional development programmes. The following sections report the processes and outcome of the instruments development. Adaptation for a culturally sensitive instrument needs to consider 1) the etic/emic4 characteristics (Brislin 1993), and 2) the equivalence of language and concepts (Behling and Law 2000). Instruments development—Adaptation of R-SPQ-2FM and LVS Firstly, suitable ‘etic’ items were initially selected from SPQ and R-SPQ-2F based on face and content validity. Secondly, new ‘emic’ items which form the ‘Career Motive’ and ‘Understanding and Memorising’ subscales are added in the ‘Etic’-Investigate learning behaviour from a position outside the target culture, using constructs that are identical or near identical from across a range of cultures. ‘Emic’- Investigate learning behaviour from within the target culture, using constructs that are limited to a single culture. 4 9 instrument development process, guided by the current literature (See Dahlin and Watkins 2000; Kember et al. 1999) and adult learning contexts in Malaysia. The 43 items are grouped into 7 subscales---Deep Strategy, Deep Motive, Understanding and Memorising, Achieving Motive, Career Motive, Surface Strategy, and Surface Motive (See Kember et al.1999). Examples of items in the subscales of R-SPQ-2FM are presented in Table 2. (Insert Table 2 here) Similarly, ‘etic’ items are selected from CVS, and CCVs. ‘Emic’ items related to ‘saving face’ (Fontaine, Eu, Thean Beng, and R. Vikrama 2002), ‘religious and secular orientation’ (Abdullah and Lim 2001; Fontaine et al. 2002) are adapted in LVS as informed by values studies in Malaysia. Items selection and development of LVS are heavily guided by Table 1. Examples of items in LVS, emerged from the syntheses of the two disciplines are presented in the Table 1, third column. As this is the first attempt to operationalise values items from CVS and CCVs to the learning context, all the 23 items in LVS are modified to suit values related to the learning context in Malaysia with the intention of enhancing content and construct validity. Table 3 shows examples of how the original items in CVS are modified to suit the Malaysian learning setting. R-SPQ-2FM (the English version) was not translated as they are direct, behavioural information questions (Behling and Law 2000). LVS was translated into both Chinese and Malay languages and back-translated to verify semantic and 10 conceptual equivalence, as well as normative issues (Behling and Law 2000). Many words and idiomatic expressions were changed and adapted to local colloquialism, with the aim of increasing familiarity (Hinkin 1998). The scoring scales in both instruments were adapted to address cultural sensitivity and enhance clarity. For instance, the labels for the five point Likert scales in R-SPQ-2FM were adapted to make them meaningful to the Malaysian respondents. These modifications were made to enhance the equivalence of language and concepts. Validation of instruments and samples--2 stage analysis Since the two instruments have been substantially adapted to be culturally sensitive for Malaysian adult learners, authors like Floyd and Widaman (1995) argued that exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to be carried out first followed by confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) for more rigorous method in developing and refinement of the instrument. In a similar vein, Hinkin (1998) has argued that whilst EFA allows a researcher to test the new scales for internal consistency and content validity, CFA enables the researcher to assess the quality of the factor structure by testing the significance of the overall model, which is not possible by EFA. The pilot sample—which is the purposive sampling was adopted in stage 1 study. One hundred and one adult learners from the Klang Valley in Malaysia participated in the pilot study. These were adult learners who engaged with professional development programmes either full time or part-time in the formal settings and hence are representative of the population of interest. They were 52.5% Malays, 47.5% Chinese and 73% females. Participants ranged in age from 21-51 and 11 above and majority fell into the age range of 21-40. Sixty one percent participated in full time study and 72% were studying in a Masters programme. The main sample which has similar demographic data was involved in the stage two analysis. They were 858 participants, which made of up 62% Malays and 38% Chinese. There were 59.1% females and 83.9% of the participants ranged in age from 21-40. Seven-five percent of them participated in part time study and 71.4% of them were engaging in continuous development programmes such as Diploma in Education. Results of exploratory factor analysis Current EFA (performed with Varimax rotation, and factor loading of > 0.555) shows that there are only 4 factors extracted from R-SPQ-2FM (unlike the seven factors postulated by Kember et al.’s Model 5 (1999)). The factors were renamed as follows: Factor 1: Deep Approach (DA), Factor 2: Career Motive/Achieve Motive (CM/AM), Factor 3: Surface Approach (SA) and Factor 4: Understanding and Memorising (U&M) Table 4 shows that DA has 12 items, CM/AM has 5 items, SA has 8 items and U&M has 4 items. The reliabilities found are respectively: DA, α = 0.84, CM/AM, α = 0.8, SA, α = 0.75 and U&M, α = 0.74. (Insert Table 4 here) 5 For a sample size of 100, Hair et al.(1995) recommend using correlation matrix of coefficients greater than 0.55 for significance level of .05, and a power level of 80%, what they called ‘practically significant’ 12 DA in the current study combines items of Deep Motive and Deep Strategy scales of SPQ and R-SPQ-2F, congruent with findings on other Malaysian secondary students when LPQ (the equivalent of SPQ for secondary school students) was administered (Watkins and Ismail 1994). This is in contrast to other studies (See Fox, McManus, and Winder 2001; Watkins 2001; Zeegers 2002) which found separate Deep Motive and Deep Strategy subscales. Similar pattern is observed in SA. CM/AM also combines items from Career Motive and Achieve Motive, unlike what was postulated by Kember et al. (1999). However, the U&M scale which was extracted supported Kember et al.’s (1999) proposal to include such scale in the investigation of cultural difference in learning, in particular when Asian learners with Confucian background are involved. The LVS also extracted four factors. Whilst the factors are rather different from the original CVS and CCVS (as LVS has been adapted for learning settings), they support the literature on Confucian values and Asian learning values (see Table 1). Hence, the new scales were renamed as follows: Factor 1: Face (Face), Factor 2: Values of Learning (VL), Factor 3: Middle Way (MY) and Factor 4: Qualities of Learning (QL). Face has 8 items, VL has 3 items, MY has 4 items and QL has 6 items. The reliabilities found are respectively: Face, α = 0.84, VL, α = 0.78, MY, α = 0.76, and QL, α = 0.75 (see Table 5). (Insert Table 5 here) 13 The results in Table 5 indicate that 21 out of 29 items loaded above the cut of point of >.55. Results of confirmatory factor analysis The testing of the model for R-SPQ-2FM was guided by insights into approaches to learning, including arguments presented by Kember et al. (1999). For analysis derived from maximum-likelihood (ML) and also to reduce sensitivity to distribution, Hu and Bentler (1998) recommend using a 2-index strategy to evaluate Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) and Comparative Fit Index (CFI). This strategy has been shown to control both Type I and Type II errors (Kember, Biggs, and Leung 2004). A good fit is indicated by CFI > 0.95 and a SRMR < 0.08. These indexes are also used in other SPQ and LPQ studies (see Biggs et al. 2001; Kember et al. 2004), thus making comparison feasible. The tested higher order model with standardized paths for R-SPQ-2FM is illustrated in Figure 1—containing two higher order latent variables, named as Meaning Orientation and Reproduction Orientation. Each latent variable is corresponded to the indicators (i.e. DA) which comprise the subscales or factors (their mean values) extracted by EFA. For this model, SRMR= 0.0348, and CFI = 0.966, which indicate quite a good fit to the data. All the paths from the constructs to the items were significant at 5% level or better. The standardized path coefficients range from 0.17 to 0.79, indicating that the items are good indicators of the four constructs/scales. A low positive correlation (0.18) was observed between Meaning 14 and Reproduction latent variables, suggesting that there is consistency with the current findings and arguments of Kember et al. (2004) and Kember et al. (1999) studies. (Insert Figure 1 here) Similarly, the tested higher order model with standardized paths for LVS is illustrated in Figure 2—with latent variables labelled as Self and Others. Each latent variable is corresponded with its indicators (e.g., QL) which comprise the subscales or factors extracted by EFA. The tested model displays good fit, with SRMR=0.0434 and CFI=0.953. Additionally, all the paths from the constructs to the items are significant at 5% level or better. The standardized path coefficients range from 0.37 to 0.99, indicating that the items are good indicators of the four constructs. It is interesting to note that there is a strong positive correlation between Self and Others (r (858) =.78, p< .01). This is congruent with the literature on the concept of ‘interdependent self’ in a collectivist society such as Malaysia (Hofstede 1991; Markus and Kitayama 1991), explaining the ‘indivisible’ relationships of the individual self and the significant others. (Insert Figure 2 here) Considering i) the rigorous two-stage testing, ii) that the reliability of the data for the two instruments in these forms is good and iii) that the SRMR values are low, these results can be interpreted as an indication that the two questionnaires, used in the higher order two-factor forms with the 4 indicators, display good psychometric properties. 15 R-SPQ-2FM—Career/Achieve Motive Scale When questionnaires like SPQ are administered without adaptation in crosscultural studies, it has been assumed that similarities in factor structure reflect similarities in constructs. However, the factors CM/AM and U&M extracted in RSPQ-2FM in the current study have provided insightful evidence on the importance of considering cultural differences (the emic characteristics) in the investigation of Asian adult learners. The validation analyses show that career motivation and achieving motivation should come as one scale rather than the two different scales as postulated by Kember et. al.(1999). Support for this combination is manifested in the principles of adult learning. Principles of adult learners and findings of Asian learners have asserted that the matured learners are more concerned with the pragmatic use of knowledge, where learning is seen as a means to an end (Kember et al. 1999; Knowles 1998; McInerney 2004). Thus, seeking professional development achievement, motivated by job related reasons is clearly evident in the derivation of the CM/AM scale, where items like ‘I would see myself basically as an ambitious person and want to get to the top, whatever I do’ correlated with items like ‘I chose my present study largely because of better job situation when I finish my study’. Tweed and Lehman (2002) advocate that students with Confucian heritage who value high marks, and are concerned with career prospects, may be perceived by Westerners as unmotivated in learning, but this may not be true to Asian learners. The concern for achieving good grades in order to secure a good job in the short or long term is also evident in studies by Cheng (2001) and McInerney (2004). Cheng for instance conducted a study on Hong Kong adult learners studying the Master of Business Administration (MBA) course, and 16 maintained that there is a need to provide both extrinsic and intrinsic rewards to these part-time Hong Kong adult learners for them to effectively apply newly acquired knowledge and skills in their job. He argued that the effectiveness of the course is evaluated by the realistic transferability of the MBA knowledge and skills to workplace. Furthermore, McInerney (2004) while discussing the value of future goals, argued that there is a strong link between career motives and achievement motives, and stressed that there is no contradiction in having a future career orientation for performing a current task and being intrinsically motivated. Findings of this kind are critical to the investigation of adult learners, in particular when the ‘pragmatic’ Asian adult learners are involved. The finding of CM/AM, coupled with the argument of pragmatic characteristics of Asian adult learners, might throw light onto the current controversial debate of whether extrinsic reward has a positive or negative outcome on intrinsic motivation (Cameron 2001; Deci, Ryan, and Koestner 2001). Far from being coincidence, there is also a call to reevaluate the dichotomous view of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation (Hidi and Harackiewicz 2000) proposed by the Western theories. R-SPQ-2FM—Understand and Memorising scale Whilst the U&M scale has not been included in the previous cross-cultural studies of SPQ, the extraction of U&M is consistent with Kember et al.’s (1999) deduction on learners with Confucian background. The validation of U&M construct may also enlighten that the learning behaviour of Malaysian adult learners are influenced by cultural variables and despite their age, they do adopt memorisation 17 strategies, rather than depending only on Deep and Achieving Strategies reported by Zeegers to achieve deep learning (2001). One possible explanation for memorising being a significant learning approach of Malaysian adult learners is that understand and memorising approach has been a deeply rooted strategy practiced in particular, by the Chinese learners because of their Confucian background. Firstly, memorisation is an internalized and ingrained strategy for many Chinese learners with Confucian heritage as evident in the Dahlin and Watkins (2000) study. They found that Hong Kong students who were socialized to internalize memorising skills and content from an early age would transfer these skills and content to a later stage of learning. A parallel effect may be happening amongst adult learners in Malaysia, particularly those who have had experienced the Chinese educational system6. In this respects, the ‘Chinese educated’ Malaysian Chinese would have a stronger inclination to memorise to understand; as one of the successful means of learning the Chinese language characters is to practice repeatedly and memorise the four-character Chinese idioms. Past studies which did not consider the memorising approach when inaccurately maintaining adult learners to have failing long term and working memory, have been criticized for being biased (Merriam and Caffarella 1999). However, the current study which included the ‘emic’ interpretation of the memorising approach found memorisation for understanding to be an indigenous approach for the Malaysian knowledge workers who engaged with formal learning. ‘Chinese educational system’ refers to Malaysian schools where the medium of instruction is the Chinese language. 6 18 LVS—Face, Middle Way, Values of Learning and Qualities of Learning scales As this is the first attempt to operationalise values items from CVS and CCVs to the learning context, the findings of the 4 scales has provided thought provoking insights to Asian learning behaviour. Firstly, ‘Face’ has been a widely researched construct, in particular in the management domain (See Redding and Ng 1982), in trying to understand organizational and managers’ behaviour. Though it is a universal concept, the concern for face is seen to be more salient for the people with collectivist cultural background where the influence of the significant others are important than most other cultures (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Whilst there has been research on the association of ‘face saving’ and participation in the classroom (See Hwang, Ang, and Francesco 2002), there is a lack of understanding on the explicit impact of face on the learning process, in particular its impact on learners’ learning motives, a construct in the Presage Factor in Biggs’ 3P Model. The derivation of the ‘Face’ scale in LVS suggests the worthiness of this construct in the Asian adult learning context. Related to the influence of the significant others is also the ‘Middle Way’ construct. Collectivist societies like Malaysia tend to practise the social balancing mechanism between ‘self’ and ‘others’ to achieve harmony in the community (Markus and Kitayama 1991). Hence, the extraction of the ‘Middle Way’ scale is valuable as there has been little research to understand whether the practice of middle way principle can enhance or hinder learning, in particular amongst the adult learners who have more ‘balancing acts to juggle’ in playing different social roles in the community. The development of the ‘Values of Learning’ scale supports the findings that people with Confucian heritage placed high value on learning. It would be both intriguing and significant to know 1) whether there is any difference in the level of 19 importance placed on learning between the Malay and Chinese adult learners in Malaysia, and 2) whether the ‘priority placed on learning’ is related to the face saving behaviour or the practice of the middle way principles. The extensive published literature on the belief of effort and malleability among the Asian learners (Lau and Chan 2001; Salili 1995) is akin to the extraction of the ‘Qualities of Learning’ scale. Qualities such as ‘being persistent and committed’ are related to the belief of putting in tireless effort rather than depending exclusively on the ability to succeed in learning—a belief which is prevalent among learners with Confucian background. This quality is aptly reflected in the Chinese saying ‘失败为成功之母’ , which literally means ‘failure is the mother of success’. Interestingly, these four scales in LVS are linked to the broader scale, ‘Confucian Work Dynamism’, extracted in Bond’s study (Chinese Culture Connection 1987). Bond has argued that value items such as ‘having a sense of shame’, ‘protecting your face’, ‘filial piety’, found in the Confucian Work Dynamism scale, appeared to distinctively characterise people from the Confucian backgrounds such as Hong Kong, Taiwan and Japan. He reported that these values were also found to correlate positively with Gross National Product (GNP), suggesting that perhaps these are the fundamental Confucian values which may be responsible for the outstanding economic development of the Five Economic Dragons with Confucian heritages (CCC, 1987). Similarly, it is plausible that the four scales extracted from the LVS may be related to the outstanding academic performance of many Asian learners (See Bempechat and Drago-Severson 1999). 20 Limitation and Implication As this is the first time a value instrument has been adapted into learning settings from existing values surveys. It must be acknowledged as a limitation, although the translated and back-translated versions did not appear to have been substantially difference in terms of factor structure. Nevertheless, it needs further validation and it would be an interesting addition to studying learning in diverse cultures. Currently, due to the increasing demands of globalised and liberalised economic environment, there has been an increase in the study of culture as an explanatory variable in many cross-cultural studies in the human resource discipline (Aycan et al. 2000). However, Vijver and Leung (2000) have cautioned that one of the main issues of such studies is the concern of Western bias which is reflected in the method used or the theoretical orientations adopted. The current cross-cultural study is a humble attempt to address such issues. The study attempts to cross-fertilise knowledge from the current adult learning study with the recent emerging issues in the development of cross-cultural psychology, educational psychology and social psychology. The attempt to develop an indigenous framework provide valuable data as it displays both ‘etic’ and ‘emic’ constructs, unlike some of the cross-cultural studies which produce inconsistent findings as a result of imposed ‘etic’ methods. It is hoped that the current study has laid out some fundamental ideas for future cross-cultural research; or that these future studies would take a similar stand—to be culturally sensitive and consider robust methodology to 21 explain possible cultural differences and not to blindly import measures without adaptations. The rigorous instrument-developing on a large scale sample comparing Malay and Chinese adult learners engaging with professional development, may suggest some crucial theoretical and methodological aspects of a framework for future researchers from the human resource disciplines who are keen to investigate crosscultural issues in a learning economy. 22 References Abdullah, A., and Lim, L. 2001. Cultural dimensions of Anglos, Australians and Malaysians. Malaysian Management Review 36(2): 9-17. Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J and Stahl, G., 2000. Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 49(1): 192-221. Behling, O., and Law, K. S. 2000. Translating questionnaires and other research instruments:Problems and solutions. Papers Series on Qualitative Applications in Social Sciences, 07-131.Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bempechat, J., and Drago-Severson, E. 1999. Cross-cultural differences in academic achievement: Beyond etic conceptions of children's understanding. Review of Educational Research, 69(3): 287-314. Biggs, J. 1987a. Student approaches to learning and studying. Melbourne, Australia: Australian Council for Educational Research. Biggs, J. 1987b. Study process questionnaires manual. Melbourne: Australian Council for Educational Research. 23 Biggs, J. 2001. Enhancing learning: A matter of style or approach? In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, eds R. J. Sternberg and L. F. Zhang, 73-102. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Biggs, J., Kember, D., and Leung, D. Y. P. 2001. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71: 133-149. Billett, S. 2001. Learning in the workplace. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen and Unwin. Brislin, R. 1993. Understanding cultures' influence on behavior: Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College Publishers. Brown, J. S., Collins, A., and Duguid, P. 1989. Situated cognition and the culture of learning. Educational Researcher, 18(1): 32-42. Buchanan, J., and Others. 2001. Beyond flexibility: Skills and work in the future. Paper presented at the Future of work, working, learning and prospering: The challenge of the emerging economy, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia. Cameron, J. 2001. Negative effects of reward on intrinsic motivation-A limited phenomenon: Comment on Deci, Koestner, and Ryan. Review of Educational Research, 71(1): 29-42. 24 Chen, C. S., Stevenson, H. W., Hayward, C., and Burgess, S. 1995. Culture and academic achievement: Ethnic and cross-national differences. In Advances in motivation and achievement: Culture, motivation and achievement, eds Maehr and R. Pintrich, 119-151. London: JAI Press Inc. Chinese Culture Connection. 1987. Chinese values and the search for cultural-free dimensions of culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 18(2): 143164. Dahlin, B., and Watkins, D. 2000. The role of repetition in the processes of memorising and understanding: A comparison of the views of German and Chinese secondary school students in Hong Kong. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 70: 65-84. Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., and Koestner, R. 2001. The pervasive negative effects of rewards on intrinsic motivation: Response to Cameron 2001. Review of Educational Research, 71(1): 43-51. Drucker, P. F. 1999. Knowledge-worker productivity: The biggest challenge. California Management Review, 41(2): 79-94. Falk, I., and Smith, T. 2002. Leadership in vocational educational and training. Adelaide, Australia: National centre for Vocational Education Research Ltd. 25 Fan, Y. 2000. A classification of Chinese culture. Cross-Cultural Management-An International Journal, 7: 3-10. Floyd, F. J., and Widaman, K. F. 1995. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychological Assessment, 7(3): 286-299. Fontaine, R., Eu, G., Thean Beng, T., and R. Vikrama, O. K. A. P. 2002. The values of young Malaysians. Paper presented at the Academy of International Business South East Asia Region (AIBSEAR), Shanghai, China. Fox, R. A., McManus, I. C., and Winder, B. C. 2001. The shortened Study Process Questionnaire: An investigation of its structure and longitudinal stability using confirmatory factor analysis. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71: 511-530. Hai, H. 2004. Educating Singaporeans on cultural intelligence: Enhancing the competitive edge. Paper presented at the Educational Research Association of Singapore- Innovation and Enterprise: Education for the New Economy, Institute of Education, Singapore. Hair, J. F. J., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and Black, W. C. 1995. Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall. 26 Hidi, S., and Harackiewicz, J. M. 2000. Motivating the academically unmotivated: A critical issue for the 21st century. Review of Educational Research, 70(2): 151-170. Hinkin, T. R. 1998. A brief tutorial on the development of measures for use in survey questionnaires. Organizational Research Methods, 1(1): 104-121. Hofstede, G. (1991). Management in a multicultural society. Malaysian Management Review, 26(1): 3-12. Hussin, H. 1997. Personal values and identity structure of entrepreneurs: A comparitive study of Malay and Chinese entrepreneurs in Malaysia. In Entrepreneurship and SME research: On its way to the next millennium, eds R. Donckels and A. Miettinen, 33-45. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. Hwang, A., Ang, S., and Francesco, A. M. 2002. The silent Chinese: The influence of face and Kiasuism on student feedback-seeking behaviour. Journal of Management Education, 26(1): 70-98. Jarvis, P. 2006. Towards a comprehensive theory of human learning: Lifelong learning and the learning society. London: Routledge. Kember, D., Biggs, J., and Leung, Y. P. 2004. Examining the multidimensionality of approaches to learning through the development of a revised version of the 27 Learning Process Questionnaire. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 74: 261-279. Kember, D., Wong, A., and Leung, D. Y. P. 1999. Reconsidering the dimensions of approaches to learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 69: 323343. Knowles, M. (1998). The adult learner. Houston: Gulf Publishing Company. Kolb, D.A. 1976. The Learning Style Inventory: Technical manual. Boston: McBer and Company. Lau, K.-L., and Chan, D. W. 2001. Motivational characteristics of under-achievers in Hong Kong. Educational Psychology, 21(4): 417-430. Li, J. 2001. Chinese conceptualization of learning. Ethos, 29(2): 111-124. Markus, H. R., and Kitayama, S. 1991. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2): 224-253. Mayo, A. 2003. Human capital: How to measure the value of our people? Retrieved (November 17), http://www.hrforumeurope.com/conference/2002session.asp?ref=a6 28 McInerney, D. M. 2004. A discussion of future time perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 16(2): 141-151. Merriam, S. B. 2001. Andragogy and self-directed learning: Pillars of adult learning theory. In The new update on adult learning theory, ed S.B. Merriam (Ed.), 4-13. San Francisco: Jossey Bass. Merriam, S. B., and Caffarella, R. S. (1999). Learning in adulthood: A comprehensive guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Novak, J. D. 1998. Learning, creating and using knowledge: Concept maps as facilitative tools in schools and corporations. New Jersey, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associaties, Inc., Publishers. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.2001. Cities and regions in the new learning economy; Education and skills. Paris: OECD. Orpen, C. 2003. Teaching students to manage cross culturally. Cross-Cultural Management, 10(2): 80-86. Pillay, H., Boulton-Lewis, G., Wilss, L., and Rhodes, S. 2003. Conceptions of work and learning at work: A challenge to emerging practices. Journal of Education and Work, 16(4): 427-445. 29 Redding, G. S., and Ng, M. 1982. The role of 'Face' in the organizational perceptions of Chinese managers. Organization Studies, 3(3): 201-219. Richardson, J. T. E. 1995. Mature students in higher education: An investigation of approaches to studying and academic performance. Studies in Higher Education, 20(1): 5-14. Robinson, C. 2001. The implications of globalisation and aging population on skills formation in Australia. Melbourne, Australia: National Centre for Vocational Education and Research. Rosen, R. T., Digh, P., Singer, M., and Phillips, C. 2000. Global literacies: Lessons on business leadership and national cultures. A landmark study of CEOs from 28 countries. New York: Simon and Schuster. Salili, F. 1995. Explaining Chinese students' motivation and achievement: A socialcultural analysis. Advances in Motivation and Achievement, 9: 73-118. Schwartz, S. H., and Sagie, G. 2000. Value consensus and importance: A crosscultural study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(4): 465-497. Sijuwade, P. O. 2001. A comparative study of family characteristics of AngloAmerican high achievers. International Educational Journal, 2(3): 161-167. 30 Stephenson, J. 1999. Corporate capability: Implications for the style and direction of work-based learning. Sydney, Australia: Research Centre for Vocational Education and Training, University of Technology, Sydney. Stevenson, H. W., and Lee, S.-Y. 1990. Context of achievement: A study of American, Chinese, and Japanese children. Monographs of Society for Research in Child Development, 55(1-2): 1-120. Tan, P. L. 2006. Approaches to learning and learning values: An investigation of adult learners in Malaysia., Unpublished doctoral thesis, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Australia. Tweed, R. G., and Lehman, D. R. 2002. Learning considered within a cultural context: Confucian and Socratic Approaches. American Psychologist, 57(2): 89-99. Vijver, V. D.,and Leung, K. 2000. Methodological issues in psychological research on culture. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(1): 33-51. Volet, S. E., Renshaw, P. D., and Tietzel, K. 1994. A short-term longitudinal investigation of cross-cultural differences in study approaches using Biggs' SPQ questionnaire. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64: 301-318. Watkins, D. 2001. Correlates of approaches to learning: A cross-cultural metaanalysis. In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles, eds R. J. 31 Sternberg and L. F. Zhang, 165-195. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Watkins, D.,and Ismail, M. 1994. Brief research report: Is the Asian learner a rote learner? A Malaysian perspective. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19: 483-488. Zeegers, P. 2001. Approaches to learning in science: A longitudinal study. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71:115-132. Zeegers, P. 2002. A revision of the Biggs' Study Process Questionnaire (R-SPQ). Higher Education Research and Development, 21(1): 73-92. 32 Tables and Figures Table 1: Consistency between literatures on cultural values presented by educational psychologists and value items developed by social psychologists ______________________________________________________________________________ Summary of literature in chapter 2 on Confucian values and learning Values items related to learning found in both CVS and CCVS (Presented by educational Psychologists) (presented by social psychologists) * Values studies on Malaysians from the management discipline Examples of items in LVS ______________________________________________________________________________________ Importance of education Knowledge /Education, Having a degree* Belief of effort and human Persistence, Perseverance* To value the pursuit of Education (item 9) Being persistent Malleability when I learn (item 2) Pragmatic learning Adaptability, Resourcefulness Having the value of wisdom/ resourcefulness when I learn (item 12) Influence of social groups (parents andpeers) face when Conformity/Group orientation, obligation to one’s family, Having to save family Care for face* I learn (item 16) ______________________________________________________________________________________ 33 Table 2: Examples of items in the subscales of R-SPQ-2FM Deep Approach Subscales Deep Motive Understanding and Memorising I find that at times studying gives me a feeling of deep personal satisfaction (Item 4) I repeat many times so that I can understand (Item 30) Deep Strategy I make a point to read up most of the references/books suggested by the lecturers (Item 25) __________________________________________________________________________________ Deep or Surface Continuum Subscales Achieve Motive One of the most important considerations in choosing a course is whether or not I will be able to get top marks/grades in it. (Item 11) Career Motive I am at university mainly because I feel that I will be able to obtain a better job if I have a higher academic qualification (Item 1) Surface Approach Subscales Surface Motive Surface Strategy I do not find my study very interesting so I keep my effort to the minimum (Item 10) I find the best way to pass the examinations is to spot questions (Item 33) 34 Table 3: Examples of how the original items in CVS are modified to learning situation Original items from CVS (How important is this item to me personally?) Adapted items of LVS (How important is this item to me…) Persistence Being persistent when I learn Knowledge/Education To value the pursuit of education 35 Table 4: Summary of Scales and Items for R-SPQ-2FM (N=101) _____________________________________________________________________ Cronbach’s Total Variance Alpha Values (%) ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 Deep Approach 12 .84 13.90 (DA) Factor Name of Factor Number of Items 2 Career/Achieve Motives (CM/AM) 5 .80 9.89 3 Surface Approach (SA) 8 .75 9.81 4 Understand and 4 .74 7.77 Memorising (U&M) ___________________________________________________________________________ Total 29 41.37 ___________________________________________________________________________ 36 Table 5: Summary of Scales and Items for LVS (N=101) _____________________________________________________________________ Cronbach’s Total Variance Alpha Values (%) ___________________________________________________________________________ 1 Face 8 .84 13.03 Factor Name of Factor Number of Items 2 Values of Learning (VL) 3 .78 12.56 3 Middle Way (MY) 4 .76 11.95 4 Qualities of Learning 6 .75 7.77 (QL) ___________________________________________________________________________ Total 21 45.31 ___________________________________________________________________________ 37 .79 ME e1 CMAM e2 UM e3 SA e4 .48 .45 .18 DA .54 RE .17 .58 Figure 1: Latent structure of R-SPQ-2FM at scales level Note: i) Observed Variables: DA=Deep Approach CM/AM= Career Motive/Achieve Motive UM=Understand and Memorising SA=Surface Approach ii) Latent Variables: ME = Meaning Orientation RE = Reproductive Orientation iii) Measurement Errors e1 to e4 Note: i) Single headed arrows represent regression paths and are notated with standardized path coefficients; double arrows represent co-variances and notated with correlation coefficients; rectangular boxes represent observed variables and ellipses represent unobserved or latent variables. 38 QL e1 VL e2 .55 .99 Self .78 .57 Others FACE e3 MY e4 .37 Figure 2: Higher order latent structure of LVS at scales level Note: i) Observed Variables: QL=Qualities of learning VL=Values of learning MY=Middle way FACE= Face ii) Latent Variables: Self Others iii) Measurement Errors e1 to e4 Note: i) Single headed arrows represent regression paths and are notated with standardized path coefficients; double arrows represent covariances and notated with correlation coefficients; rectangular boxes represent observed variables and ellipses represent unobserved or latent variables. 39 Biographical Note Dr Po Li, Tan is a lecturer in Higher Education at The Learning Institute, King’s College London. Her main research interest includes cross-cultural issues and adult learning, cross-cultural coaching, cross-cultural methodology, intercultural sensitivity development and internationalisation of higher education. Her current project involves supporting international teachers at higher education using cross-cultural coaching. She can be contacted by email: po_li.tan@kcl.ac.uk 40