Introduction

advertisement

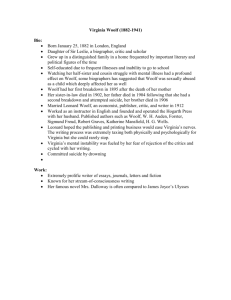

Introduction This work was originally written under the supervision of prof. dr. hab. Leszek S. Kolek in the English Philology Institute of UMCS as a doctoral dissertation. It was then titled “Philosophy and Narrative: The Novels of Virginia Woolf.” In preparing the work for publication I have decided to change the title, fearing that it might mislead the reader into believing that the work is a study of Virginia Woolf’s fiction, whereas in fact it is a methodological study. This focus of the book appears to be more adequately expressed in the new title “Philosophy in Fiction.” The primary aim of this work is to present and test a method of reconstructing the philosophy present in narrative literature. The method might help facilitate an objective and comprehensive reading of narrative texts, as well as contribute to the defence of the scholarly character of those literary studies which venture beyond purely formal descriptions. The dissertation consists of an introduction, two parts, and a conclusion. The first part presents a theory of the philosophical analysis of narrative texts;1 the second contains three analyses of Virginia Woolf’s novels, The Years (1937), Jacob’s Room (1922) and Between the Acts (1941), which illustrate both the invariable narrative structure and the three major narrative variants – realist, modernist and postmodernist – all examined in terms of their philosophical content. To keep the dissertation within reasonable limits I have decided to exclude particular examples from the first, theoretical, part, and to omit from the second, practical, part full-length analyses of Virginia Woolf’s other novels, enclosing merely their brief presentations in so far as these shed light on additional aspects of the relationship between narrative and philosophy. For detailed presentation I have selected three novels which are very original, and yet relatively neglected by critics, even though I realize that they are not the purest in terms of the literary convention they are taken to represent (Night and Day, To the Lighthouse and Orlando might in this respect serve as better examples of realism, modernism and postmodernism, respectively). Nor do they reflect Woolf’s 1 Fragments of the theoretical part of this dissertation have already been published or publicly presented (now in print): Teske, Joanna (Klara). “The Novel: A Store of Ideas vs. a Mode of Cognition.” PASE Papers in Literature, Language and Culture. Lublin, 1998. 377-386. ---. “Treść formy, czyli o literaturze i o tym jak forma uwikłana jest w wymianę poglądów między autorem a czytelnikiem.” Aspekty filozoficzno-prozatorskie. 9-16. (2004-5): 30-9. ---. “The Philosophical Potential of Narrative Texts.” 14th PASE Conference, Łódź 4-7 April, 2005. Introduction 6 literary evolution (The Years is Woolf’s last novel but one, but in this dissertation it must be studied first, since the literary convention it is taken to represent is historically older than modernism or postmodernism); however, it is not the purpose of this dissertation either to reconstruct Woolf’s philosophy or trace her literary evolution. The reason this study in the philosophical interpretation of narrative works is illustrated with the novels of Virginia Woolf, when in principle it can be illustrated with any narrative, any English novel, is, apart from my personal preference (any choice in this situation is, out of necessity, arbitrary), the unusual versatility of Woolf’s literary method and originality of her philosophical thought – under these circumstances the study of her fiction should be particularly illuminating. I have taken great care to do justice to the critics who for decades have been examining Virginia Woolf’s novelistic output, above all with reference to the formal analysis of the narrative techniques and their interpretation. Sometimes, however, respecting the division of the novel’s narrative spheres of dominance (of the characters, narrator and implied author) I could not take advantage of critical works of less systematic approach. The published version of my dissertation is complemented by two essays: “The Three Stages in the History of the Novel – Realism, Modernism and Postmodernism: A Reflection of the Evolution of Reality in Karl Popper’s Model of the Three Worlds” and “Sanity, Neurosis and Psychosis in the Modern History of the English Narrative.” I originally presented them at the 16th PASE Conference (Szczyrk, 19-21. 04. 2007) and “The Cultural Representations of Psychiatry and Mental Illness” conference (Piotrków Trybunalski, 18-19. 05. 2007) respectively. I would like to express here my sincere gratitude for the kind permission of the editors of the conference proceedings to republish them here. The papers develop two hypotheses briefly discussed in my dissertation (section 3.4) concerning the analogy between the three literary conventions (realism, modernism and postmodernism) and, on the one hand, Popper’s Worlds (the first essay) and, on the other hand, the three states of the human mind (the second), with reference to the history of the English novel. Some paragraphs from section 3.4 are repeated in the essays enclosed in the appendix, for the sake of their clarity and self-contained character. I would also like to take this opportunity to reveal two general methodological principles of my analysis. Firstly, I believe that the reconstruction of the philosophical content of narrative works should not use as evidence either biographical materials or critical works by the author. The author who articulates his/her view of reality Introduction 7 in narrative fiction does not, as a rule, expect the reader to be well acquainted with the author’s biography or beliefs expressed elsewhere – the text of the narrative should, for the sake of such analysis, be treated as self-contained and self-sufficient. Secondly, I will employ the criterion of internal cohesion of the text devised by St Augustine and discussed by Umberto Eco in his lecture on overinterpretation: “any interpretation given of a certain portion of a text can be accepted if it is confirmed by, and must be rejected if it is challenged by, another portion of the same text” (Eco, “Overinterpreting Texts” 65). I should like to explain at this point why I have decided to exclude from my discussion deconstructionist authors (such as Jacques Derrida, Paul de Man or their followers), even though they have been closely concerned with the relationship between philosophy, literature and literary theory. The main reason is that deconstructionists have deliberately neglected the distinction between the three disciplines, arguing that they all use the same language with its figurative and rhetorical mode. My aim being the construction of a method of reading the philosophical ideas inherent in narrative texts, I have not found this approach helpful. Furthermore, deconstructionists have relinquished the basic assumptions of modern (rational-empiricist) science such as the concept of truth, the search for objective, free-of-ideology knowledge and the distinction between the subject and object of research. Although I appreciate the value of the deconstructionist method of reading, intent as it is on finding the text’s multiplicity of meaning, contradictions and paradoxes, I am unwilling to accept their view of the humanities, and this is the second reason why I could not take advantage of their works. Finally, I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Leszek S. Kolek for agreeing to assist me in my struggle with Virginia Woolf, for the freedom he gave me to explore the common realm of literature and philosophy, for the attention with which he critically examined the results of my exploration, and for the many years of his generous help. I would also like to express my sincere thanks to Professor Aleskandra Kędzierska and Professor Jacek Wiśniewski, who reviewed this dissertation, for their valuable comments. For their support and help, I would like to thank my colleagues from the English Department of the John Paul II Catholic University of Lublin, and above all, the head of the Department, Professor Anna Malicka-Kleparska. Last but not least, I would like to thank the staff of the English Department Library at KUL and the British Council Library, the students who attended my course on English Literature (From Modernism to Contemporary Fiction), my friends and family. I would like to dedicate this book to my parents, Elżbieta and Andrzej Teske.