Shabbat Bereshit

advertisement

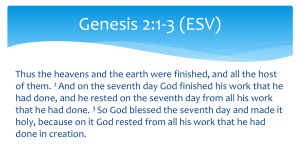

Bar-Ilan University Parashat Hashavua Study Center Shabbat Bereshit 5772/ October 22, 2011 Lectures on the weekly Torah reading by the faculty of Bar-Ilan University in Ramat Gan, Israel. A project of the Faculty of Jewish Studies, Paul and Helene Shulman Basic Jewish Studies Center, and the Office of the Campus Rabbi. Published on the Internet under the sponsorship of Bar-Ilan University's International Center for Jewish Identity. Prepared for Internet Publication by the Computer Center Staff at Bar-Ilan University. Inquiries and comments to: Dr. Isaac Gottlieb, Department of Bible, Isaac.Gottlieb@biu.ac.il. Menahem Ben-Yashar Ashkelon College Shabbat Bereshit The term Shabbat Bereshit in our literature has had three meanings: the first, in the literature of the Sages, refers to the weekly Sabbath, the day of rest established "in commemoration of Creation" (Heb. zekher le- ma`aseh bereshit). In the literature on Jewish customs and liturgy of the medieval Ashkenazi community two other meanings of this phrase appear: one refers to the very first Sabbath in the world – that which took place immediately after the six days of Creation, i.e., the Sabbath described in Genesis 2:1-3.1 The second meaning refers to the Sabbath on which the weekly portion of Bereshit is read, i.e., the first Sabbath after the festivals of the month of Tishre,2 when we begin the yearly Torah reading cycle. Just as one has a major celebration when concluding the reading cycle on Simhat Torah, so one has a minor celebration upon beginning the new cycle of readings. One could say that this Shabbat is a continuation and final touch to the festivities of Simhat Torah. The festivities of Shabbat Bereshit are often provided by the person who was honored on Simhat Torah honored as Hatan Bereshit, i.e., the person given the reading of the beginning portion of Genesis, immediately following Ve-zot ha-Berakhah, the reading which 1 2 As in the Vitri Mahzor (Horowitz ed., Jerusalem 1963), ¶103 (p. 82), ¶139 (p. 109). As in Sefer ha-Minhagim of R.Yitzhak Isaac Tirnau (14-15th c.), Hazan ed., Warsaw (1944) p. 62. 1 concludes the Pentateuch, thus symbolizing that reading and studying the Torah continues in an unbroken chain forever.3 Today all three senses of Shabbat Bereshit are meant: it is a weekly day of rest on which we read Parashat Bereshit, which tells of the very first Sabbath, that Sabbath on which the Lord rested, having completed all His work. We turn now to the well-known question regarding the text of Scripture at the end of the description of Creation: "On the seventh day G-d finished the work that He had been doing" (Gen. 2:2) – but did He not finish His work on the sixth day, and rest from His work on the seventh? Indeed, the Septuagint and the Syriac translations, as well as the Samaritan version of the Bible all read: "On the sixth day G-d finished…" In so doing, according to the Sages, the Greek translators of the Torah deliberately changed the text in order to forestall this question on the part of their readers. On the basis of the philological rule of lectio difficilior,4 which means that the more difficult reading is assumed to be the original one, many modern commentators (including Shadal, in his commentary on the Torah) reaffirmed the Masoretic (our Hebrew Bible) version, "on the seventh day," which is also supported by the structure of Genesis 2:2-4, written in the style of amplified prose, as follows (translated literally, so as to reveal the Hebrew structure better): 2:2 2:3 G-d finished and He rested And G-d blessed and sanctified He rested G-d had created on the seventh day on the seventh day the seventh day it the work that He had been doing from all the work that He had done. because on it from all His work that to do. Written in this manner, we see a striking three-way structure: four components appear three times each: the name G-d (Elohim); "the seventh day"; and "[all] His/the work"; and the verb "do," which concludes each of the clauses in this passage. The first two lines (verse 2) are parallel and almost identical in structure, except that the holy name, G-d, is missing in the second line, since in terms of the three-way structure it needs to come at the end of the passage. Taken together, the two parallel verbs at the beginning of the two lines comprising verse 2 describe the concluding moments of creation: the Holy One, blessed be He, had concluded His work of creation and therefore He rested from it. Note that in this week's reading we have a three-fold repetition of the expression, "on the seventh day from all the work that He had done." It appears thus in verse 2, and in verse 3 in split form: the verse begins with "G-d" and towards the end comes "from all the work … to do [Heb. la`asot instead of `asa, the form in which the verb appeared earlier]." The three-fold repetition is for the three times that similar passages appear throughout the Torah regarding the Sabbath day 3 Jewish communities in Franco-Germany used to incorporate special liturgical poems in their morning prayer service on the Sabbath of Bereshit. These poems can be found in certain prayer books, such as Seder Avodat Yisrael, redacted by Z. Baer, Redelheim 1868, pp. 624-627. 4 Without actually using this terminology, Shadal describes what it refers to at length. That the reading in the Masoretic text, "on the seventh day," was widespread among the Jews at the end of the Second Temple period is proven by the quote in Paul's Epistle to the Hebrews, 4.4. 2 observed by the Israelites: twice in the two versions of the fourth commandment – "but the seventh day is a sabbath of the Lord your G-d: you shall not do any work,"5 – and the third time, also in somewhat different formulation, at the beginning of the passage summarizing the festivals and holy days: "You shall do no work; it shall be a sabbath of the Lord" (Lev. 23:3). As we mentioned, this passage concludes with the word la`asot (rendered literally as "to do"), alongside the previous two instances of concluding verses with `asa (rendered above as "had been doing" and "had done"). Commentators wonder as to the syntax and import of the word la`asot. It would have sufficed to write, "because on it He rested from all His work that G-d had created." Benno Jacob says that the two verbs, creating and doing [bara Elohim la'asot], are needed as a ceremonious conclusion to the process in which G-d "makes" [also `asa] and "creates [bara]."6 Indeed, this is so, yet it still does not suffice to explain the meaning of the word la`asot in the last clause. Reviewing the classical exegetes, we find that Rashi follows the Sages' remarks in Genesis Rabbah: "Two expressions are used because on the sixth day G-d did two acts of creation, also making whatever was to have been made on the seventh day."7 Ibn Ezra and, following him, also Radak explain that G-d created the world in such a manner that by nature things would continue to be made [la'asot means "to (continue) to do"]. Nahmanides writes: "Created to do" because on the first day He created (bara) matter ex nihilo, so that of this material He could create (la'asot) on the remaining days of Creation." This suggestion seems plausible: G-d created the raw material on the first day, in order to fashion out of it the rest of Creation. Let us return to the symmetry of the verses 2:2-3. The third clause of 2:3 concludes with the verb "to do," matching the concluding words of the previous two clauses. On the other hand, the entire account of Creation concludes with the words: "which G-d created," mirroring the opening words of the Torah, "In the beginning G-d created.""8 As for the question we raised above, if G-d finished His work on the sixth day, how can Scripture say, "G-d finished on the seventh day"? Both early commentators, such as Ibn Ezra and Radak, and later ones, such as Luzzatto (Shadal), Cassuto, and Benno Jacob, interpret "he finished" as meaning pluperfect "he had already completed." Cassuto and Benno Jacob prove this from other instances of the same root, k-l-h,9 and Cassuto even deduced that expressions such as "va-yekhal" and "va-tekhal," when followed by another verb, mean that since He had already completed one action, he was now embarking on another. In our case, Gen.2:2, G-d having completed His work, he therefore rested, blessed, and sanctified that day. This string of verbs begins and ends with the root sh-b-t, to rest (vayishbot, ki vo shavat), intimating that this lies at the foundation of the commandment of the Sabbath, a day of rest. 5 Ex. 20:10, Deut. 5:14. These two verbs appear 3 times each in the account of Creation: "G-d created" (in verses 1, 21, and 27); "G-d made" (verses 7, 16, 25). 7 Cf. Genesis Rabbah 11.2, which lists three things that were created on each day and six things for the sixth day. In modern times we might refer to two separate categories of creation: the animals that live on land, and human beings. 8 So wrote M. D. Cassuto, Perush al Sefer Bereshit, Part 1, Jerusalem 1959, p. 44. 9 Cassuto, ibid., on Gen. 17:22, 24:19, 49:33 (pp. 38-39); Benno Jacob proves this from the reckoning of days in II Chron. 29:17. 6 3 The commandment itself which is called the Sabbath is not mentioned until the people of Israel appear in the world and are given the Sabbath, shortly after the exodus from Egypt, even before the Theophany at Mount Sinai. Along with the tangible blessing of manna from heaven, Israel is given the spiritual blessing of the Sabbath (Ex. 16). There G-d translates into action that which appears as an abstract notion in this week's reading, for at the time there was not yet a people of Israel to observe the Sabbath. Thus Rashi interprets the verses in our parasha, citing the Sages:10 "And G-d blessed – with a double portion of manna on the sixth day, and He sanctified it – by having the manna not come down. Thus He illustrated and showed Israel their first Sabbath, as Scripture says: 'Mark that the Lord has given you the sabbath' (Ex. 16:29)." Based on this precedent, G-d could command them at Sinai, "Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy" (Ex. 20:8). 10 Genesis Rabbah 11.10. 4