"Richard Cory" Literary Criticism: Analysis & Essays

advertisement

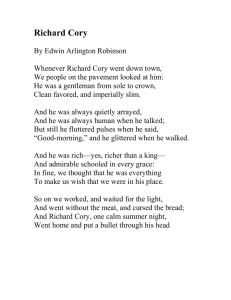

Literary Criticism ________________________________________________________________ Edwin Arlington Robinson "Richard Cory" Lloyd Morris The dramatist sets in operation a chain of circumstances in which his characters are unconsciously brought to book by their own past. The method of the naturalistic novelist is quite different; absolved of the necessity of a demonstration, he tends to be less and less concerned with incident and to become preoccupied with the effect of experience on character; the drama is purely internal and is revealed by minute and acute psychological analysis. When this method is applied to dramatic material the very absence of the terms in the demonstration essential to the dramatist produces the effect of irony. Consider, for example, Richard Cory: Here we have a man's life-story distilled into sixteen lines. A dramatist would have been under the necessity of justifying the suicide by some train of events in which Richard Cory's character would have inevitably betrayed him. A novelist would have dissected the psychological effects of these events upon Richard Cory. The poet, with a more profound grasp of life than either, shows us only what life itself would show us; we know Richard Cory only through the effect of his personality upon those who were familiar with him, and we take both the character and the motive for granted as equally inevitable. Therein lies the ironic touch, which is intensified by the simplicity of the poetic form in which this tragedy is given expression. from The Poetry of Edwin Arlington Robinson: An Essay in Appreciation. First published in 1923. Reissued in 1969 by Kennikat Press (Port Washington, N.Y.) Ellsworth Barnard Form in poetry, however, as has been said, involves not only adherence to a central story or theme, but some kind of progress or development toward a final effect to which each particular part has made its particular contribution. A simple and famous illustration is Richard Cory . . . . We need not crush this little piece under a massive analysis; a few more or less obvious comments will suffice to show how carefully the poem is put together. The first two lines suggest Richard Cory's distinction, his separation from ordinary folk. The second two tell what it is in his natural appearance that sets him off. The next two mention the habitual demeanor that elevates him still more in men's regard: his apparent lack of vanity, his rejection of the eminence that his fellows would accord him. At the beginning of the third stanza, "rich" might seem to be an anticlimax—but not in the eyes of ordinary Americans; though, as the second line indicates, they would not like to have it thought that in their eyes wealth is everything. The last two lines of the stanza record a total impression of a life that perfectly realizes the dream that most men have of an ideal existence; while the first two lines of the last stanza bring us back with bitter emphasis to the poem's beginning, and the impassable gulf, for most people— but not, they think, for Richard Cory—between dream and fact. Thus the first fourteen lines are a painstaking preparation for the last two, with their stunning overturn of the popular belief. To repeat this sort of analysis for each of Robinson's poems would be as profitless as tedious to most readers, who will want to do it themselves if they want it done at all. We may, however, dwell a little on some of the patterns that the poet likes to follow. And first of all, it is to be observed that the structure of Richard Cory—the steady buildup to the surprise ending in the last line, is not characteristic. This fact fits in with what was said in the preceding chapter about Robinson's handling of the sonnet, and the quiet, unhurried close that he most often gives it; as well as with what has been all along implied concerning his distaste for every sort of sensationalism. But sometimes, as in Richard Cory, a different turn of mind reveals itself, perhaps sprung from the perception that life does have surprises, that sometimes only at the very last do we find the key piece that makes the hitherto puzzling picture all at once intelligible. from Edwin Arlington Robinson: A Critical Study. Copyright © 1952 by the MacMillan Company. J.C. Levenson "Richard Cory" conceals its powerful particularity by appearing almost tritely conventional. But since the surprise ending of Cory’s suicide does not, after a first reading, surprise anyone but the "we" of the poem, it is worth looking for deeper causes of its hold on readers. One the one hand, there is Robinson’s tact in presenting the title figure. By his scheme, moral blindness is overcome, not by factitious insight into another mind, but by respectful recognition of another person. So he avoids the nineteenth-century, common-sense method of realistic characterization and gives us nothing of his subject’s motives or feelings. He sketches in Cory’s gentlemanliness and his wealth, but not his despondency, and he lets the suicide seal the identity of the man forever beyond our knowing or judging. On the other hand, he can characterize the chorus just because they lack individuality, and he invites us to judge their blindness on pain of missing the one sure meaning of the poem: So on we worked, and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; And Richard Cory, one calm summer night, Went home and put a bullet through his head. They do not serve who only work and wait. Those who count over what they lack and fail to bless the good before their eyes are truly desperate. The blind see only what they can covet or envy. With their mean complaining, they are right enough about their being in darkness, and their dead-gray triviality illuminates by contrast Cory’s absolute commitment to despair. From Edwin Arlington Robinson: Centenary Essays. Ed. Ellsworth Barnard. Copyright © 1969 by the University of Georgia Press. Wallace L. Anderson In April 1897 Robinson, reporting the local news to Harry Smith, wrote "Frank Avery blew his bowels out with a shot-gun. That was bell." By the end of July he had completed, he told Miss Brower, "a nice little thing . . . . There isn't any idealism in it, but there’s lots of something else - humanity, may be. I opine that it will go." It has become one of the most familiar of Robinson's poems. But poems, like people, sometimes suffer from what familiarity so often breeds. This is especially true if the work appears to be fairlv simple and uncomplicated. It may be what led Yvor Winters to remark that "In 'Richard Cory' . . . we have a superficially neat portrait of the elegant man of mystery; the poem builds up deliberately to a very cheap surprise ending; but all surprise endings are cheap in poetry, if not, indeed, elsewhere, for poetry is written to be read not once but many times." This remark is itself surprising, for not all surprise endings are cheap, nor does a surprise ending prevent a work from being read with pleasure more than once. The use of surprise is a legitimate device that occurs in all literary forms. The issue is not whether the reader has been surprised but whether the author has so prepared his ground that the ending is a justifiable one, consistent with the total context. Actually, "Richard Cory" has a rich complexity that becomes increasingly rewarding with successive readings. A wealthy man, admired and envied by those who consider themselves less fortunate than he, unexpectedly commits suicide. Cory's portrait is drawn for us by a representative man in the street, who depicts him as "imperially slim," "a gentleman from sole to crown," "richer than a king." An individual set apart from ordinary mortals, Cory is, in their opinion, a regal figure in contrast to his admiring subjects, "the people on the pavement." This contrast between Cory and the people, seemingly weighted in favor of Cory in the first three stanzas, is the key to the poem. Nowhere are we given direct evidence of Cory's real character; we are given only the comments of the people about him, except for his last act, which speaks for itself. Ironically, Cory's suicide brings about a complete reversal of roles in the poem. As Cory is dethroned the people are correspondingly elevated. The contrast between the townspeople and Cory is continued in the last stanza. The people worked, and waited for the light, And went without the meat, and cursed the bread; but they went on living. Cory, wealthy as he was, did not live; instead, be "put a bullet through his head." This occurred "one calm summer night." Calm, that is, to the people, not to Cory. Because the people "went without the meat, and cursed the bread," it might seem that life was both difficult and meaningless to them. But difficulty is not to be equated with meaninglessness; in fact, Robinson is suggesting just the opposite. "Meat" and "bread" carry biblical overtones that remind us that man does not live by bread alone. It is "the light" that gives meaning. In opposition to meat and bread, symbols of physical nourishment and material values, light suggests a spiritual sustenance of greater value. As such it clarifies the intent of the poem, for it reveals the inner strength of the people and the inadequacy of Cory. Belief in the light is the one thing the people had; it is the one thing Cory lacked. Life for him was meaningless because he lacked spiritual values; he lived only on a material level. Once this is realized, the characteristics attributed to Cory in the first three stanzas take on added significance and become even more ironic: He was "a gentleman from sole to crown" (appearance and manner); he was "clean favored" and "slim" (physical appearance); he was "quietly arrayed" (dress); he was "human when he talked" (manner); he "glittered" (appearance); he was "rich" (material possessions); he was "schooled in every grace" (manner). "Glittered" not only emphasizes the aura of regality and wealth but also suggests the speciousness of Cory. Even his manner is not a manifestation of something innate but only a characteristic that has been acquired ("admirably schooled"). All these details are concerned with external qualities only. The very things that served to give Cory status also reveal the inner emptiness that led him to take his own life. From Edwin Arlington Robinson: A Critical Introduction. Copyright © 1967 by Wallace L. Anderson.