To Kill a Mockingbird Film notes.doc

advertisement

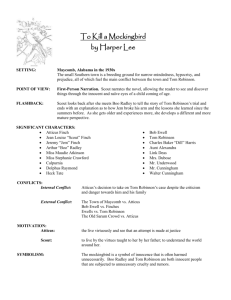

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962) is a much-loved, critically-acclaimed, classic trial film. It exhibits a dramatic tour-de-force of acting, a portrayal of childhood innocence (told from a matured adult understanding), and a progressive, enlightened 60s message about racial prejudice, violence, moral tolerance and dignified courage. The Academy Award winning screenplay was faithfully adapted by screenwriter Horton Foote from the 1960 novel of the same name by Harper Lee - who had written a semi-autobiographical account of her small-town Southern life (Monroeville, Alabama), her widower father/attorney Amasa Lee, and its setting of racial unrest. [This was Lee's first and sole novel - and it won the Pulitzer Prize in 1960.] The poor Southern town of deteriorating homes was authentically recreated on a Universal Studios' set. Released in the early 60s, the timely film reflected the state of deep racial problems and social injustice that existed in the South. The film begins by portraying the innocence and world of play of a tomboyish six year-old girl named Scout (Mary Badham) and her ten year-old brother Jem (Phillip Alford), and their perceptions of their widower attorney father Atticus (Gregory Peck). They also fantasize about a 'boogeyman' recluse who inhabits a mysterious house in their neighborhood. They are abruptly brought out of their insulated and carefree world by their father's unpopular but courageous defense of a black man named Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) falsely accused of raping a Southern white woman. Although racism dooms the accused man, a prejudiced adult vengefully attacks the children on a dark night - they are unexpectedly delivered from real harm in the film's climax by the reclusive neighbor, "Boo" Radley. The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards, including Best Picture (producer Alan J. Pakula lost to the epic Lawrence of Arabia (1962)), Best Director (Robert Mulligan), Best Supporting Actress (Mary Badham, sister of director John Badham, known for Saturday Night Fever (1977), Stakeout (1987), and other films), Best B/W Cinematography (Russell Harlan), and Best Music Score - Substantially Original (an evocative score by Elmer Bernstein). It was honored with three awards - Gregory Peck won a well-deserved Best Actor Award (his first Oscar win and fifth Oscar nomination) for his solid performance as a courageous Alabama lawyer, Horton Foote won the Best Adapted Screenplay Oscar (Foote won a second Oscar for Tender Mercies (1983)), and the team of Art Directors/Set Decorators also received the top honor. [Although Gregory Peck's inspirational performance as Atticus Finch turned out to be a perfect highlight to his long career, Rock Hudson was actually the studio's first choice for the role.] Relationships formed during filming would last for the remainder of Gregory Peck's life -- he received the pocketwatch of Harper Lee's father; he became the surrogate father to Mary Badham; and Brock Peters delivered Peck's eulogy after his death in June of 2003. The black-and-white film opens with a wonderfully-fashioned credit sequence - beginning with an overhead point-of-view shot of a young girl opening and looking into a old cigar box of collected remembrances, valued treasures and trinkets, including: crayons (new and used) a mechanical pencil two carved soap doll figurines - one male and one female an old broken pocket watch a skeleton key a broken pocket knife a spelling medal a few marbles jacks an Indian head and Lincoln head penny a chalk holder and other minor objects As she sings, hums and giggles to herself, she colors over lined paper with a round crayon, revealing the title of the film in white letters. The camera circles and tracks slowly from left to right along various collections of carefully-arranged objects in magnified close-up, while nostalgic music plays (Elmer Bernstein's lyrical score): the broken pocket watch on a chain a large safety pin and a chain Indian head and Lincoln head pennies a mechanical pencil a translucent marble a jack a black and white striped marble that rolls and collides with a black marble a beaten-up crayon a disembodied pen point another clear marble a button the broken pocket watch on a chain (again) a harmonica another multi-colored marble a silver whistle After drawing a simple, stick-figured 'mocking-bird', the girl shades in the winged creature and then tears the paper through the bird, melodramatically foreshadowing the racial tensions and divisions that will tear apart the innocence of the town and forever alter the child's fragile memories. The camera descends on a sleepy view of a small, languid town, Maycomb, Alabama, in the early 1930s at the height of the Depression. The story is poignantly and sentimentally told from the eyes of a six year old tom-boy - Jean Louise "Scout" Finch (9 year-old Mary Badham in her film debut). [Her character represents the novel's author. Finch was the middle name of Harper Lee's father. Also, a mockingbird and a Finch are both songbirds.] Uncredited Kim Stanley narrates the film in voice-over as an adult version of Scout. She intelligently recalls where she grew up, in a small Southern town, where "the day was 24 hours long, but it seemed longer": Maycomb was a tired old town, even in 1932 when I first knew it. Somehow, it was hotter then. Men's stiff collars wilted by nine in the morning. Ladies bathed before noon after their three o'clock naps. And by nightfall were like soft teacakes with frosting from sweating and sweet talcum. The day was twenty-four hours long, but it seemed longer. There's no hurry, for there's nowhere to go and nothing to buy...and no money to buy it with. Although Maycomb County had recently been told that it had nothing to fear but fear itself...That summer, I was six years old. Early one morning, one of the poor farmers from the countryside hit hard by the Depression, Walter Cunningham (Crahan Denton) drives through town in a horse-drawn wagon. Ill at ease and embarrassed, he delivers a crokersack full of hickory nuts to the clapboard Finch residence as part of his entailment for legal work. The previous week, he had brought "delicious" collards as payment. Scout, dressed in blue jeans, is swinging on a rope by the side of her house, and then leaning on a tire swing (hung on another rope). Her father is a widower defense lawyer, spectacled Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck), who is struggling to raise his two children - "Scout" and ten-year-old son Jem (13 year-old Phillip Alford in his film debut) - after his wife died four years earlier. Scout inquires about their financial status compared to that of the Cunninghams: Scout: Is he poor? Atticus: Yes. Scout: Are we poor? Atticus: We are indeed. Scout: Are we as poor as the Cunninghams? Atticus: No, not exactly. The Cunninghams are country folks, farmers. The crash hit them the hardest. A warm-hearted neighbor woman, Miss Maudie Atkinson (Rosemary Murphy), who is keenly interested in Atticus and his children, is working in her garden across the street. When Jem complains to her that his father "is too old for anything," she stoutly defends him: He can do plenty of things...He can make somebody's will so airtight you can't break it. You count your blessings and stop complaining, both of you. Thank your stars he has the sense to act his age. As Jem looks down from his treehouse into Miss Stephanie Crawford's (Alice Ghostley) collard patch next door, he spots a crouching boy sitting among the plants. They soon become friends with Charles Baker "Dill" Harris (John Megna) who is visiting his Aunt for two weeks in the summertime from Meridian, Mississippi. Dill is a peculiar, eccentric boy wise beyond his years who boasts he's "goin' on seven" and "I'm little but I'm old." [His character was based upon Harper Lee's childhood friend and neighbor, Pulitzer prize-winning author Truman Capote.] The imaginative children expect to enjoy their summer days in a tree-house, playing games, swinging on a rubber tire, and fantasizing about a neighboring house that harbors the town's pariah. They are intrigued by the creaky old wooden place, believing the frightful tale that it is occupied by a hateful man named Mr. Radley (Richard Hale) and his mentally-crazed, terrifying son - an elusive, mysterious recluse named Arthur "Boo" Radley (Robert Duvall in a stunning film debut). Jem sees Mr. Radley walk by and quiets his pals, and then they run over and stare at the Radley house and yard: Jem: There goes the meanest man that ever took a breath of life. Dill: Why is he the meanest man? Jem: Well, for one thing, he has a boy named Boo that he keeps chained to a bed in the house over yonder...See, he lives over there. Boo only comes out at night when you're asleep and it's pitch-dark. When you wake up at night, you can hear him. Once I heard him scratchin' on our screen door, but he was gone by the time Atticus got there. Dill: (intrigued) I wonder what he does in there? I wonder what he looks like? Jem: Well, judgin' from his tracks, he's about six and a half feet tall. He eats raw squirrels and all the cats he can catch. There's a long, jagged scar that runs all the way across his face. His teeth are yella and rotten. His eyes are popped. And he drools most of the time. Dill's spinsterish Aunt Stephanie Crawford fills the children's myth-making minds with even more horrifying images of the fearsome Boo Radley - who hasn't been seen since his family locked him up years earlier: There's a maniac lives there and he's dangerous...I was standing in my yard one day when his Mama come out yelling, 'He's killin' us all.' Turned out that Boo was sitting in the living room cutting up the paper for his scrapbook, and when his daddy come by, he reached over with his scissors, stabbed him in his leg, pulled them out, and went right on cutting the paper. They wanted to send him to an asylum, but his daddy said no Radley was going to any asylum. So they locked him up in the basement of the courthouse till he nearly died of the damp, and his daddy brought him back home. There he is to this day, sittin' over there with his scissors...Lord knows what he's doin' or thinkin'. When the town clock strikes five, Jem and Scout run down the street to meet Atticus. On the way to town, Jem spins another cautionary tale about another neighbor - Mrs. Henry Lafayette Dubose, a peculiar, elderly woman who sits on her porch in a wheelchair and is cared for by a black woman named Jessie: Listen, no matter what she says to you, don't answer her back. There's a Confederate pistol in her lap under her shawl and she'll kill you quick as look at you. Come on. Although Scout acts slightly disrespectful toward the woman as she passes, a few moments later her father (on his return from town) calms things by taking an interest in Mrs. Dubose's beautiful flowers. Jem whispers to Scout that he understands how his father practices courteous diplomacy: He gets her interested in something nice, so she forgets to be mean. Later that evening, the camera intrudes through a gauzy curtain covering the Finch window into an intimate bedtime scene in Scout's bedroom, where she finishes reading a passage outloud to her father from Robinson Crusoe. Boo Radley is still on her mind and she asks Atticus about him, and then inquires about Atticus' watch - economically revealing emotional feelings about the missing Mrs. Finch: Scout: Atticus, do you think Boo Radley ever really comes and looks in my window at night? Jem says he does. This afternoon when we were over by their house... Atticus (interrupting and admonishing): Scout. I told you and Jem to leave those poor people alone. I want you to stay away from their house and stop tormentin' them. Scout: Yes, sir. Atticus (after checking his pocket watch): Well, I think that's all the reading for tonight, honey. It's gettin' late. Scout: What time is it? Atticus: Eight-thirty. Scout: May I see your watch? (She delights once more in reading the inscription in the watch.) 'To Atticus, My Beloved Husband.' Atticus, Jem says this watch is gonna belong to him some day. Atticus: That's right. Scout: Why? Atticus: Well, customary for the boy to have his father's watch. Scout: What are you gonna give me? Atticus: Well, I don't know that I have much else of value that belongs to me. But there's a pearl necklace - and there's a ring that belonged to your mother. And I've put them away and they're to be yours. (Scout stretches out her arms and smiles. He kisses and hugs her goodnight). Sitting motionless and silent on the porch swing after both his children have gone to bed, Atticus overhears his children's conversation about the mother they can barely remember or picture in their minds. In the sensitively-executed scene, the younger Scout asks her older brother (offcamera) about their late mother who died when she was too young to remember: Scout: How old was I when Mama died? Jem: Two. Scout: How old were you? Jem: Six. Scout: Old as I am now. Jem: Uh huh. Scout: Was Mama pretty? Jem: Uh, huh. Scout: Was Mama nice? Jem: Uh, huh. Scout: Did you love her? Jem: Yes. Scout: Did I love her? Jem: Yes. Scout: Do you miss her? Jem: Uh, huh. They are trying to come to terms with the ambiguities and uncertainties of their lives, and justice (and injustice) in the world. At six years of age, Scout's innocent reflections help her to contemplate and understand her circumstances. Seventy-five year old local judge, Judge Taylor (Paul Fix) drops by and informs Atticus that the grand jury will charge accused black man Tom Robinson (Brock Peters) the following day. Although the children and his practice take much of his time, the deeply-principled man reflects thoughtfully and then agrees to "take the case", defend the accused man, and represent him in the court. The next morning, Dill dares Jem (with a bet of a Grey Ghost against two Tom Swifts) to go "farther than Boo Radley's gate." Even though Jem asserts: "I ain't scared. I go past Boo Radley's house nearly every day of my life," he doesn't take the challenge as they go out into the street to play. Scout is placed in a rubber tire, given a big shove, and is accidentally rolled into the Radley's front yard. She is stunned and dizzy when the tire hits the steps of the Radley's front porch. To assist his frozen-with-fear, helpless sister, Jem takes off toward her and drags her away from danger. And then he decides to prove he's not scared and take Dill's bet. He runs up the steps to the front door, touches it, comes running down, and then races out of the yard and back home yelling: "Run for your life, Scout. Come on, Dill." When they are out of danger, they are exhausted and Jem boasts: "Now who's a coward? You tell them about this back in Meridian County, Mr. Dill Harris." Respectful of his pal, Dill suggests that they venture downtown where there are more "instruments of torture" to experience in the town's courthouse: Let's go down to the courthouse and see the room that they locked Boo up in. My aunt says it's bat-infested, and he nearly died from the mildew. Come on. I bet they got chains and instruments of torture down there. Paralleling the imaginative dreamworld of the children is another contradictory and volatile adult world of social issues. Scout and Jem reluctantly follow Dill into the courthouse hall and up to the second floor to find Atticus. [The interior of the courtroom in the film is an almost-identical copy of the Monroe County Courthouse that existed in author Harper Lee's hometown of Monroeville, Alabama.] With their assistance by making a "saddle" with their arms, Dill is hoisted up to peer in the glass window high in the tall courtroom doors. He vividly describes the scene of supposed justice during the grand jury hearing for Tom Robinson, from his own boy-hood point of view: Not much is happening. The judge looks like he's asleep. I see your daddy and a colored man. The colored man looks to me like he's crying. I wonder what he's done to cry about?...There's a whole lot of men sitting together on one side and one man is pointing at the colored man and yelling. They're taking the colored man away. Atticus, dressed in a three-piece white linen suit, is appalled that his children are there and sends them back home immediately. The respected, incorruptible Atticus quickly becomes embroiled in a hostile world of hatred and prejudice. Poor 'white trash' redneck Robert E. Lee (Bob) Ewell (James Anderson), the father of the alleged rape victim Mayella Violet Ewell (Collin Wilcox), blocks Atticus' way and questions his decision to take the case and vigorously defend a black man: I'm real sorry they picked you to defend that nigger that raped my Mayella. I don't know why I didn't kill him myself instead of goin' to the sheriff. That would have saved you and the sheriff and the taxpayers lots of trouble... Ewell even threatens Atticus' children: "What kind of a man are you? You got chillun of your own." That evening, Dill and Jem decide to sneak up to the Radley house where the porch swing creaks - with a scared and nervous Scout following behind them - to "look in the window of the Radley house and see if we can get a look at Boo Radley." The three crawl and squeeze under a high wire fence at the rear of the Radley property and cautiously approach the house. At the ramshackle back porch, Jem creeps up the noisy steps toward one of the windows and tries to peer in. Suddenly, a large shadow of a man appears, moves across the porch and looms over him - crossing over his body. A menacing hand reaches out. All of them cover their eyes and cower in sheer fright, but then the image retreats just as mysteriously. They leap off the porch and back under the fence, but Jem's overalls get snagged in the wire mesh - he discards his pants (with Scout's and Dill's assistance) to get untangled and free and then runs toward home in his underwear. To avoid being whipped by his father for not having his pants, Jem disappears through the fence to go back and retrieve his abandoned overalls - it is a tense few moments as Scout slowly counts to fourteen, hoping that her brother (off-screen) will return. Her counting is interrupted by the sound of a shotgun blast. Jem bursts through the hole in the fence, just as Mr. Radley appears with his shotgun on the street, telling Atticus and Aunt Stephanie that he "shot at a prowler out in his collard patch." With summer ending and Dill returning to his home, school begins. Tomboy Scout must give up her overalls for a dress. She awkwardly pokes and tugs at it on her first day of school: "I still don't see why I have to wear a darn old dress." In the schoolyard, her natural outspokenness, honesty and candor get her into a tussle with Walter Cunningham Jr., (Steve Condit), the seven year-old son of the farmer from Old Sarum. She rubs his nose in the dirt. Scout explains to Jem, as he restrains her with all his might, why she took out her frustration at the teacher on the poor boy: He made me start off on the wrong foot. I was trying to explain to that darn lady teacher why he didn't have no money for his lunch, and she got sore at me. Jem promises that his "crazy" sister won't fight with him any more and then invites young Walter over to the Finch household for a dinner of roast beef (corn bread, turnips and rice) rather than his usual fare of "squirrels and rabbits." During the meal, Atticus explains the responsibility his father taught him in using his first gun when he was thirteen or fourteen - and how it is 'a sin to kill a mockingbird' - a songbird that harmlessly exists only to give pleasure: I remember when my daddy gave me that gun. He told me that I should never point it at anything in the house. And that he'd rather I'd shoot at tin cans in the backyard, but he said that sooner or later he supposed the temptation to go after birds would be too much, and that I could shoot all the blue jays I wanted, if I could hit 'em, but to remember it was a sin to kill a mockingbird...Well, I reckon because mockingbirds don't do anything but make music for us to enjoy. They don't eat people's gardens, don't nest in the corncribs, they don't do one thing but just sing their hearts out for us. Scout watches Walter as he liberally pours thick syrup all over his meal. Appalled and disgusted, she hurts his feelings: "He's gone and drown-ded his dinner in syrup and then he's pourin' it all over." In the kitchen, the black housekeeper Calpurnia (Estelle Evans) gives Scout a lesson about manners and tolerance: That boy is your company. And if he wants to eat up that tablecloth, you let him, you hear? And if you can't act fit to eat like folks, you can just set here and eat in the kitchen. Scout is sent back to the table with a smack on her rear. With a caring understanding of the mysteries of childhood, Atticus finds Scout on the slatted porch swing hanging on a rusty chain and sits next to her. He listens to her share her feelings about the crisis on her first day of school, and her criticisms of her teacher. Without talking down to her, he eloquently, simply, and tenderly presents her with an invaluable lesson on how to accept the differences between one human being and another: If you just learn a single trick, Scout, you'll get along a lot better with all kinds of folks. You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view...Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it. With paternal wisdom, he also tells her about the meaning and value of compromising: Atticus: Do you know what a compromise is? Scout: Bendin' the law? Atticus: Uh, no. It's an agreement reached by mutual consent. Now, here's the way it works. You concede the necessity of goin' to school, we'll keep right on readin' the same every night, just as we always have. Is that a bargain? As the scene continues, the adult Jean-Louise - in voice-over - praises her father: There just didn't seem to be anyone or anything Atticus couldn't explain. Though it wasn't a talent that would arouse the admiration of any of our friends, Jem and I had to admit he was very good at that, but that was all he was good at, we thought. In the next memorable sequence, Atticus proves his Lincoln-esque stature to his children. Although Scout is disbelieving and yells out "He can't shoot" when Sheriff Heck Tate (Frank Overton) hands his rifle to her father, Atticus takes aim with a rifle at a rabid dog moving erratically down the street outside their home. He raises up his glasses a few times on his forehead to see better, and then removes them altogether by dropping them on the street. Jem and Scout are both dumbfounded and stunned when the rifle cracks and the dog flops over dead. The Sheriff tells Jem about the hidden abilities of his modest father who hasn't shot a gun in twenty years: "Didn't you know your daddy's the best shot in this county?" That night, Jem and Scout join their father as he rides into the country to compassionately talk to his client's family - twenty-nine year-old Helen Robinson (Kim Hamilton), the wife of the man he is defending. While Atticus is in the Robinson house, an unshaven and drunken Bob Ewell staggers toward the car, holds onto it to steady himself, and stares at the two children. Atticus appears and after they face off, Ewell hatefully snarls at him: "You nigger lover." Jem's understanding of the world is altered and he needs reassurance: "No need to be afraid of him, son. He's all bluff." As they drive away, the camera takes Jem's point-of-view as he watches the prejudiced, gesturing and threatening figure standing in the middle of the road. When they return home, Atticus adds: "There's a lot of ugly things in this world, son. I wish I could keep 'em all away from you. That's never possible." While Atticus drives Calpurnia home, Jem sits on the porch in the rocking chair. He is spooked and terrorized by rustling trees, moving shadows, and the calls of a nightbird. He starts to run toward the Radley place in the direction of his father's car, calling out: "Atticus, Atticus." Realizing it is futile to try to catch up to the car, he stops and turns toward home at the edge of the Radley property, noticing something shiny and reflective in the moonlight - in the hollow knothole of an old oak tree. He sticks his hand in, takes the object out, notices it is a shiny medal, and quickly pockets it before running home. While Scout argues and fights at school with another boy, this time Cecil Jacobs (Kim Hector), the adult voice of Jean-Louise remembers the incident that provoked her: Atticus had promised me he would wear me out if he ever heard of me fightin' any more. I was far too old and too big for such childish things, and the sooner I learned to hold in, the better off everybody would be. I soon forgot...Cecil Jacobs made me forget. Later that afternoon on the Finch front porch, Scout sits with her head buried in her arms. She reveals to Atticus the 'fightin'' words that caused her to beat up another neighborhood boy to defend her father's work: Scout: Atticus, do you defend niggers? Atticus: Don't say 'nigger,' Scout. Scout: I didn't say it...Cecil Jacobs did. That's why I had to fight him. Atticus (sternly): Scout, I don't want you fightin'! Scout: I had to, Atticus, he... Atticus (interrupting): I don't care what the reasons are. I forbid you to fight. Atticus patiently explains his reasons for making the unpopular decision to defend a Negro - a most-hated and despised person in society, regardless of the consequences: Atticus: There are some things that you're not old enough to understand just yet. There's been some high talk around town to the effect that I shouldn't do much about defending this man. Scout: If you shouldn't be defending him, then why are you doing it? Atticus: For a number of reasons. The main one is that if I didn't, I couldn't hold my head up in town. I couldn't even tell you or Jem not to do somethin' again. (He puts his arm around her.) You're gonna hear some ugly talk about this in school. But I want you to promise me one thing...that you won't get into fights over it, no matter what they say to you. In the knothole, both Jem and Scout find two carved soap figurines - one the figure of a boy and the other a girl with a crude cloth dress. They realize that the playthings have a resemblance to themselves: "Look, the boy has hair in front of his eyebrows like you do...Yeah - and the girl wears bangs like you - these are us!" Suddenly, Mr. Radley comes from behind the tree and starts filling the knothole with cement from a trowel. That night, Jem shows Scout the contents of a cigar box after forcing her to promise "never to tell anybody." In it is the growing collection of items that he has found in the knothole - including a crayon, marbles, a whistle, a spelling medal, an old pocket watch, and a pocketknife. And he reveals another secret - when he went back to fetch his tangled britches, they were neatly "folded across the fence - sorta like they was expectin' me." An adult Jean-Louise comments about the mystery: It was to be a long time before Jem and I talked about Boo again. When school finally ends, summer and Dill arrive again. The trial of Tom Robinson is scheduled for the following day, and the defendant is brought back into town from the Abbottsville jail where he was held for safe-keeping. That night, Atticus decides to stand guard outside the town jail because of rumoured agitation from "that bunch out at Old Sarum." Later that night, the three children run from the Finch house toward the jail through deserted and dark streets. From behind bushes in the town's square, they notice a solitary light burning in the distance. While reading a law book under a lamp shade he has brought from home, Atticus is seated in a chair propped up in front of the jail's front door where Tom Robinson is being held. Jem is satisfied: "I just wanted to see where he was and what he was up to. He's all right. Let's go back home." In one of the most compelling scenes in the film, as the children begin taking a shortcut home, four cars noisily converge on the jail from the Meridian Highway. The children hide and watch from the cover of the bushes. The armed men get out of their cars and surround Atticus - they are a self-appointed lynch mob that has gathered to take justice into its own hands after diverting Sheriff Tate. To get a closer look, the three kids run over to the cars. Scout, in particular, who is oblivious to the danger, pushes her way through the crowd to glimpse her stern-faced father - he immediately fears for their safety. While Jem stands by his father and stubbornly refuses to leave after his father's command, a stalwart Scout faces down the crowd and sees someone she recognizes. She conducts an innocent, uninhibited exchange with Walter Cunningham Sr., and engages him in a disarming, candid, yet humanized conversation. Scout makes him uncomfortable in front of the mob: I said, 'Hey,' Mr. Cunningham. How's your entailment getting along? (He turns and looks away.) Don't you remember me, Mr. Cunningham? I'm Jean Louise Finch. You brought us some hickory nuts one early morning, remember? We had a talk. I went and got my daddy to come out and thank you. I go to school with your boy. I go to school with Walter. He's a nice boy. Tell him 'hey' for me, won't you? You know something, Mr. Cunningham, entailments are bad. Entailments...(She suddenly becomes self-conscious) Atticus, I was just saying to Mr. Cunningham that entailments were bad but not to worry. Takes a long time sometimes...(To the men who are staring up at her) What's the matter? I sure meant no harm, Mr. Cunningham. Scout's words cause him to break up the potential lynching. The embarrassed crowd disbands. The next day, the explosive trial brings scores of country people to town to watch the case unfolding in the rural Southern courthouse. Although the children have been ordered to say home, Jem can't resist being there with them: "I'm not gonna miss the most excitin' thing that ever happened in this town!" The courthouse square is empty, but the courthouse is filled with spectators. Because the downstairs is "packed solid," elderly black Baptist minister Rev. Sykes (Bill Walker) lets the children join the blacks that are consigned to the 'colored' balcony on three sides of the courtroom. They peer over the balcony railing onto the scene below. The jury, seated to the left under long windows, is composed nearly entirely of farm folk who haven't been able to avoid jury duty. The courtroom sequences are dramatically-filmed. In the opening testimony by Sheriff Tate to the circuit solicitor Mr. Gilmer (William Windom), it is learned that on the night of August 21st, Bob Ewell reported the beating and rape (she was "taken advantage of") of his girl, Mayella Violet Ewell (Collin Wilcox). It is simply the word of two white people against the word of a black man. During cross-examination by Atticus, Tate reveals that nobody called a doctor: "she was beaten around the head. There were bruises already comin' on her arms. She had a black eye startin' an'... - it was her left." But then after some clarification, he corrects himself: It was her right eye, Mr. Finch. Now I remember. She was beat up on that side of her face...She had bruises on her arms and she showed me her neck. There were definite finger marks on her gullet...I'd say they were all around. The next witness is Mayella's father Bob Ewell, who testifies that when he came home that night, he heard his daughter screaming and found Robinson on top of her before chasing him from the house: "I seen him with my Mayella...po' Mayella was layin' on the floor squallin'." During crossexamination, Atticus hands paper and pencil to Ewell and has him write his name to discover that he is left-handed. The children watch everything very intently from the balcony ledge. Ewell angrily complains to the judge: "That Atticus Finch is tryin' to take advantage of me. You gotta watch lawyers like Atticus Finch." Mayella, a "white trash" woman accustomed to strenuous labor, takes the stand next and testifies that she invited Tom inside her yard to do chores. That was when he attacked her in the house: I was sittin' on the porch, and he come along. Uh, there's this old chifforobe in the yard, and I-I said, 'You come in here, boy, and bust up this chifforobe, and I'll give you a nickel.' So he-he come on in the yard and I go in the house to get him the nickel and I turn around, and 'fore I know it, he's on me, and I fought and hollered, but he had me around the neck, and he hit me again and again, and the next thing I knew, Papa was in the room, a-standin' over me, hollerin', 'Who done it, who done it?' During cross-examination, she reveals that her father is usually "tol'able" ("good" or "easy to get along with") except when he's drinking. Although she asserts that her father "never touched a hair o' my head in my life," he could beat her when "he's riled" - drinking. Evasively, she is uncertain whether the critical day was the first time she had ever asked him to come inside the fence. And she can't recollect "if he hit me" but then changes her mind. When Miss Mayella identifies the attacker as the defendant Tom Robinson, Atticus asks him to catch a water glass tossed at him he does so with his right hand. Tom explains that his left arm is useless: I can't use my left hand at all. I got it caught in a cotton gin when I was twelve years old. All my muscles were tore loose. Mayella's testimony is disjointed, confusing, and forced, and leaves no doubt that she is lying. Cornered when Atticus asks: "Do you want to tell us what really happened?", she loses her composure. The naive, beleaguered woman grimly shouts toward the accused black man and the jury, and then runs from the witness stand to elicit sympathy: I got somethin' to say. And then I ain't gonna say no more. He took advantage of me. An' if you fine, fancy gentlemen ain't gonna do nothin' about it, then you're just a bunch of lousy, yella, stinkin' cowards, the - the whole bunch of ya, and your fancy airs don't come to nothin'. Your Ma'am'in' and your Miss Mayellarin' - it don't come to nothin', Mr. Finch, not...no. Tom Robinson takes the stand to testify and states that he had to pass the Ewell place going to and from the field every day. For over a year, Mayella had often invited him inside the fence to do chores, but he never charged her: "Seemed like every time I passed by yonder, she'd have some little somethin' for me to do, choppin' kindlin', and totin' water for her." On the night of the alleged beating and rape, Mayella invited Tom inside the house to fix a door that didn't need fixing - it was uncharacteristically quiet with all seven children in town getting ice cream with seven nickels she had saved to treat them ("She said it took her a slap year to save seb'm nickels..."). Uncomfortable with the next bit of testimony, Tom's nostrils flare and his forehead breaks out into a nervous sweat: Well, I said I best be goin', I couldn't do nothin' for her, an' she said, oh, yes I could. An' I asked her what, and she said to jus' step on the chair yonder an' git that box down from on top of the chifforobe. So I done like she told me, and I was reachin' when the next thing I know she...grabbed me aroun' the legs. (A murmur erupts in the courthouse) She scared me so bad I hopped down an' turned the chair over. That was the only thing, only furniture 'sturbed in the room, Mr. Finch, I swear, when I left it....Mr. Finch, I got down off the chair, and I turned around an' she sorta jumped on me. She hugged me aroun' the waist. She reached up an' kissed me on the face. She said she'd never kissed a grown man before an' she might as well kiss me. She says for me to kiss her back. (Tom shakes his head, re-living the ordeal with his eyes half-closed) And I said, Miss Mayella, let me outta here, an' I tried to run. Mr. Ewell cussed at her from the window and said he's gonna kill her. Although Tom unequivocally denies raping or harming Mayella Ewell in any way, Gilmer establishes that the defendant was "strong enough" to hurt the woman. The prosecutor also insinuates some ulterior motive on Tom's part: "How come you're so all-fired anxious to do that woman's chores?" Tom reveals that he performed the chores for free - and foolishly admits that he felt sorry for the white woman: Tom: Looks like she didn't have nobody to help her. Like I said... Gilmer: With Mr. Ewell and seven children on the place? You did all this choppin' and work out of sheer goodness, boy? Ha, ha. You're a mighty good fella, it seems. Did all that for not one penny. Tom: Yes, sir. I felt right sorry for her. She seemed... Gilmer: You felt sorry for her? A white woman? You felt sorry for her? Later that day, Atticus bravely proves the innocence of his client in a final, low-keyed defense summation to the emotionless jury. He begins by stating that the case never should have been brought to trial: "The State has not produced one iota of medical evidence that the crime Tom Robinson is charged with ever took place." He asserts that the testimony of Mayella was "called into serious question" and was "flatly contradicted by the defendant." Atticus uses the testimony about Tom's useless left hand to illustrate that the white girl Mayella ("the victim of cruel poverty and ignorance") couldn't have been struck by Tom Robinson. She was savagely struck, beaten, and raped by someone who was left-handed [Mayella was clearly injured from a beating by her father]. He vigorously and powerfully argues that Mayella lied because she broke a code that prohibits a white woman from becoming sexually attracted to a black man - an unspeakable offense: ...in an effort to get rid of her own guilt. Now I say guilt, gentlemen, because it was guilt that motivated her. She has committed no crime, she has merely broken a rigid and time-honored code of our society. A code so severe that whoever breaks it is hounded from our midst as unfit to live with. She must destroy the evidence of her offense. But what was the evidence of her offense? Tom Robinson - a human being. She must put Tom Robinson away from her. (He gestures, pushing away with his hands.) Tom Robinson was to her, a daily reminder of what she did. Now what did she do? She tempted a Negro. She was white, and she tempted a Negro. She did something that in our society is unspeakable. She kissed a black man. Not an old uncle, but a strong, young Negro man. No code mattered to her before she broke it, but it came crashing down on her afterwards. Atticus asserts that the Ewell witnesses thought, with "cynical confidence," that they could get away with their false testimony and trusted that the jury would agree with them. His argument is convincing - Mayella failed in seducing Tom Robinson, and then falsely accused him of rape after being beaten by her father for making sexual advances toward a black man. Atticus looks into the eyes of the jury with quiet authority, patience, fair-mindedness, and a strong sense of right and wrong, arguing further that it should not be assumed that all whites tell the truth and all black people lie: The witnesses for the State, with the exception of the Sheriff of Maycomb County, have presented themselves to you gentlemen, to this court, in the cynical confidence that their testimony would not be doubted. Confident that you gentlemen would go along with them on the assumption, the evil assumption, that all Negros lie, that all Negroes are basically immoral beings, all Negro men are not to be trusted around our women. An assumption that one associates with minds of their caliber, and which is in itself, gentlemen, a lie, which I do not need to point out to you. And so, a quiet, humble, respectable Negro, who has had the unmitigated temerity to feel sorry for a white woman, has had to put his word against two white peoples. The defendant is NOT GUILTY, but somebody in this courtroom is. His final appeal to the jury to acquit the defendant and show moral courage is presented with dignity and eloquence: Now gentlemen, in this country, our courts are the great levelers. In our courts, all men are created equal. I'm no idealist to believe firmly in the integrity of our courts and of our jury system. That's no ideal to me. That is a living, working reality. Now I am confident that you gentlemen will review - without passion - the evidence that you have heard, come to a decision, and restore this man to his family. In the name of God, do your duty. In the name of God, believe Tom Robinson. Several hours later, the jury returns to the courtroom. Despite a convincing defense, the case is hopeless from the start - the accused black man is convicted by the prejudiced white jury. Atticus tells Tom as he is handcuffed and led from the court that he plans to appeal: "I'll go to see Helen first thing in the morning. I told her not to be disappointed, we'd probably lose this time." After the courtroom clears, Atticus gathers his papers and walks down the middle aisle in defeat. The blacks in the balcony stand to show dignified respect as he passes out the courtroom door. Rev. Sykes alerts Scout to stand in his honor: Miss Jean Louise, stand up, your father's passin'. Although Atticus' defense has caused him to suffer many injustices, his compassionate defense has won him the respect and admiration of his two motherless children and the black community. Later that night, neighbor Maudie Atkinson commiserates with Atticus' loss and summarizes for a disappointed Jem the thankless work that his father does in a world of human irrationality: "There are some men in this world who are born to do our unpleasant jobs for us. Your father's one of them." After hearing from Sheriff Tate, Atticus explains that Tom fled from the authorities and was shot to death while supposedly trying to escape: Tom Robinson's dead. They were taking him to Abbottsville for safekeeping. Tom broke loose and ran. The deputy called out to him to stop. Tom didn't stop. He shot at him to wound him and missed his aim. Killed him. The deputy says Tom just ran like a crazy man. The last thing I told him was not to lose heart, that we'd ask for an appeal. We had such a good chance. We had more than a good chance. At the Robinson home where Atticus goes to deliver the bad news to the family (to Helen and Spence, Tom's father), Helen collapses when she senses that Tom is dead. A hate-filled, disgraced Bob Ewell confronts Atticus in the yard and after glaring spits into his face. With spit rolling down his cheek, Atticus defiantly steps forward, glares back, wipes the spit from his face with a handkerchief, and climbs into the car. By the next fall, the memories of the trial have faded, as adult Jean Louise remembers in voiceover: By October, things had settled down again. I still looked for Boo every time I went by the Radley place. This night my mind was filled with Halloween. There was to be a pageant representing our county's agricultural products. I was to be a ham. Jem said he would escort me to the school auditorium. Thus began our longest journey together. Jem escorts Scout to the school building to attend the Saturday night pageant. Scout carries a giant ham costume that she will wear for Halloween. When it's almost ten o'clock and time to return home, Scout has to wear her ham costume because she has lost her dress and shoes: "I'll feel like a fool walking home like this." In a moving camera shot through the dark wooded area between the school and their home, the trees rustle around them. Stopping and starting, Jem repeatedly believes he hears heavy footsteps walking behind them in the eerie, Southern gothic sequence. To confront their ghost, Scout yells out an echoing retort: "I'll bet it's just old Cecil Jacobs tryin' to scare us. (Yelling) Cecil Jacobs is a big wet hen." Jem guides his sister with a hand on her costume while looking back and hearing distinct footsteps. A shadowy form attacks Jem and hurls him to the ground. As she struggles to get out of her awkward, cumbersome ham costume, Scout is thrown down and rolls around inside the protective outfit. She hears scuffling, grunting, kicking, and pounding sounds as Jem wrestles against his attacker and shouts "Run, Scout!" He is seriously injured and rendered unconscious. When the assailant [a disgraced Bob Ewell] turns toward Scout, a second pair of hands intervene from an unseen man - they wrestle with her attacker and come to her defense. Through the viewhole of the ham, Scout watches in wide-eyed horror as the scuffling sounds of a second struggle die down and there is silence. From her point of view, she watches a pair of legs cross her path and under a street light, she sees Jem's limp body being carried home by a mysterious person. After removing her costume, Scout follows closely behind and sees her brother being carried into the Finch yard. Atticus runs down the steps of his house and picks Scout up in his arms, asking: "What happened?" He alerts Calpurnia to get the doctor and then phones Sheriff Tate to report: "Someone's been after my children." Jem has been found unconscious, bruised, and lying on his bed inside his room. Dr. Reynolds (Hugh Sanders) diagnoses a badly-fractured arm: "...like somebody tried to wring his arm off." The Sheriff arrives with Scout's ham costume and reveals a disturbing find in the woods to a shocked Atticus: Bob Ewell's lyin' on the ground under that tree down yonder with a kitchen knife stuck up under his ribs. He's dead, Mr. Finch....He's not gonna bother these children any more. As Scout relates what happened, she notices a man in the corner of the bedroom behind the door - she identifies him as the one who grabbed Mr. Ewell and carried Jem home: Why, there he is, Mr. Tate. He can tell you his name... The Sheriff moves the bedroom door, revealing in the light a terrified, gentle man with a pale face, thin blonde hair, white skin, and dark shaded eyes - a brain-damaged, ghostly Boo Radley (Robert Duvall finally makes his crucial appearance in a non-speaking role, his first film role), who appears to have spent much of his life locked in a sun-deprived environment (a cellar?). As he returns a protective, loving look, Scout gazes at him with wonder in her eyes and then a timid smile breaks out on her face. Now a flesh and blood character who turned out to be her guardian angel, she no longer fears him as the horrible ghost of her fantasies: Scout: Hey Boo. Atticus: Miss Jean Louise, Mr. Arthur Radley. I believe he already knows you. Scout goes to him, takes his hand and leads Arthur over to Jem's bed to say goodnight. Jem is asleep - his left arm in a cast. She encourages him to tenderly touch Jem: "You can pet him, Mr. Arthur. He's asleep. Couldn't if he was awake, though. He wouldn't let you. Go ahead." She leads "Boo" out to the front porch where they sit quietly on the rocking swing. At first, Atticus believes that Jem had killed Ewell and that there must be a defense established: "It'll have to come before the County Court. Of course, it's a clear-cut case of self-defense." Sheriff Tate enlightens Atticus: Mr. Finch, do you think Jem killed Bob Ewell? Is that what you think? Your boy never stabbed him. They look up toward Boo and Scout who sit peacefully on the swing. Boo would have to be defended in court, but would never be able to survive the notoriety of a trial. To atone for his errors in judgment in the Robinson/Ewell case and for the death of an innocent man, the Sheriff proposes a cover-up to protect the harmless, innocent Boo from "the limelight" of public prosecution. He fabricates a story, asserting that Ewell drunkenly fell and was killed on his own knife. Ignoring the prospect of Atticus' defense of Boo, the Sheriff speculates that Atticus may not want to participate in the cover-up of the truth: Bob Ewell fell on his knife. He killed himself. There's a black man dead for no reason, and now the man responsible for it is dead. Let the dead bury the dead this time, Mr. Finch. I never heard tell it was against the law for any citizen to do his utmost to prevent a crime from being committed, which is exactly what he did. But maybe you'll tell me it's my duty to tell the town all about it, not to hush it up...To my way of thinkin', takin' one man who's done you and this town a big service, and draggin' him, with his shy ways, into the limelight, to me, that's a sin. It's a sin, and I'm not about to have it on my head. I may not be much, Mr. Finch, but I'm still Sheriff of Maycomb County, and Bob Ewell fell on his knife. Scout rises from the swing and walks over to her father - he puts her up at eye-level on a chair. Scout affirms Sheriff Tate's wisdom, revealing her own grown-up understanding that it would be inhumane to subject Boo to a defense trial even if it could be proven that he killed Ewell to protect them - it would be an egregious sin to "kill a mockingbird": Scout: Mr. Tate was right. Atticus: What do you mean? Scout: Well, it would be sort of like shooting a mockingbird, wouldn't it? (They hug each other closely) Boo rises and walks over to peer in Jem's window. Atticus walks over to Boo and shakes his hand in gratitude, concurring with the Sheriff's decision to hush-up the killing: Thank you, Arthur. Thank you for my children. The conclusion of the film is moving and melodramatic, especially with Elmer Bernstein's poignant closing score. In a backwards moving shot, Scout walks the timid Boo Radley (with his hand in hers) to the Radley gate and up their front walk. Jean Louise, in her adult voice-over, narrates the remainder of the film's dialogue: Neighbors bring food with death, and flowers with sickness, and little things in between. Boo was our neighbor. He gave us two soap dolls, a broken watch and chain, a knife, and our lives. Boo opens the door to his own house and goes inside. Scout lingers for a few moments on the front porch and at the front gate before slowly returning home. She views the world from a new angle - from Boo's perspective. In her awakening intelligence and perception of the nature of good and evil, and right and wrong, she senses what Atticus had earlier told her about never really understanding a person "until you consider things from his point of view...until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it": One time Atticus said you never really knew a man until you stood in his shoes and walked around in them. Just standin' on the Radley porch was enough. The summer that had begun so long ago had ended, and another summer had taken its place, and a fall, and Boo Radley had come out. The film concludes with memories of her childhood: her brother, her friends, justice, and her father. The camera pulls out of the window in Jem's room, where Scout is cradled in her father's arms, to a long shot of the Finch house: I was to think of these days many times. Of Jem and Dill and Boo Radley, and Tom Robinson and Atticus. He would be in Jem's room all night, and he would be there when Jem waked up in the morning.