Terracotta Army.doc

advertisement

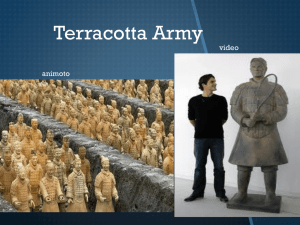

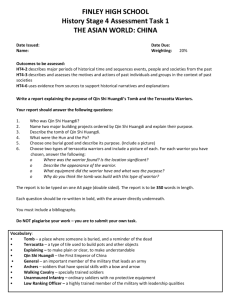

The Terracotta Army Political Ideologies and Artistic Production Andrew Wilkinson: #66715187 In 221BCE, the Qin state defeated Qi, the last of six rivals. The Warring States Period that lasted over 255 years had finally ended; and thus the Qin state became an empire, with King Zheng as the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di. China was for the first time in history, united. 1 While Zheng’s rule of the Qin dynasty lasted for less than 11 years, many of the ambitious projects he undertook still stand today, such as a nationwide road network, a standardized Chinese script (later simplified by the Communist party,) an early version of the Great Wall (the wall as it stands now was mostly constructed during the Ming dynasty, however) and the subject of this essay, the Terracotta Warriors of Qin Shi Huang. This essay explores and analyzes how the political climate during the short reign of the Qin dynasty is reflected in the Terracotta Army. Built to accompany the First Emperor into the afterlife, the Terracotta Army was buried near Zheng, less than 2 kilometres from his tomb at Mount Li – a tremendous complex which remains buried to this day. The Terracotta Army, (consisting of over 7,000 clay warriors, many of them armed with bronze weaponry) was made possible through the period of peace brought on by Qin’s conquests. It is also a triumph of organization and bureaucracy, and a reflection of Zheng’s (instigated in the state of Qin by Shang Yang many years earlier) abolition of feudalism in favour of a Legalist meritocracy. The army and tomb also represent a symbol of power and might – only an Emperor as great and godlike as Qin Shi Huang could possibly command such power in the afterlife. 1 Jane O’Connor, The Emperor’s Silent Army (New York: The Penguin Group, 2002), p. 10 I could rewrite the essay to be about the process of building the Terracotta Army and how every stage of it was influenced by political concerns? Will do this if it looks like it’ll flow naturally when I’ve written the rest of the initial draft. Peacetime, Organization, Bureaucracy The very scale of the Terracotta army is a reflection of the political climate during the Qin dynasty. Sima Qian, the Han historian, stated that over 700,000 labourers were employed in the construction of the tomb complex and army. 2 In The Terracotta Army, John Man rejects this number as highly unrealistic and exaggerated, and estimates approximately 25,000 men were involved. 3 In either case, thanks to the conquest and unification of China, a large portion of the population previously devoted to the war effort was freed up to act as labour for the first emperor’s tomb. War would have acted as a constraint to not only the labour forces, but the provision of weaponry as well – for every soldier in the Terracotta Army bore bronze arms, still razor sharp thousands of years later. 4 Diverting such essential resources away from the well oiled Qin war machine would have been unwise – but after victory, (having confiscated and melted the arms of the six opposing states,) such a feat became possible. The scale of the army was achieved thanks to the period of peace, but it is the organizational innovations introduced for the purposes of war (starting in 350BC with Shang Yang’s Legalist influence) which made the construction possible. The shift from small aristocratic forces to large infantry armies consisting of trained peasants required meticulous recordkeeping and organization, both of which laid the groundwork for civil bureaucracy. 5 Further to this, Edgar Kiser and Yong Cai point out that war facilitates the construction of roads, John Man, The Terracotta Army: China’s First Emperor and the Birth of a Nation, (London: Bantam Press, 2007) pp. 120-125 3 Ibid. 4 Arthur Cotterell, The First Emperor of China, (London: Macmillan London Limited, 1981), p. 48 5 Edgar Kiser and Yong Cai, ‘War and Bureaucratization in Qin China: Exploring an Anomalous Case’, American Sociological Review Vol. 68, No. 4 (Aug., 2003), pp. 515-516 2 which serve to assist centralization of government at a later stage. 6 Essentially, Qin’s militarism led directly to the later establishment of the bureaucratic system that enabled the construction of the Terracotta Army, among other large scale projects. It is fitting that the Terracotta Army acts as an example of what a militaristic state can achieve in times of peace. The highly efficient bureaucracy and readily available labour facilitated the construction of the tomb and pits, but the task of constructing the eight thousand soldiers necessary for an army was no small feat – both cost and speed of construction were major factors in the selection of the final medium: clay. 7 In the end, enormous workshops were set up near the site of the tomb, crafting each soldier’s body from a mould. 8 The heads were crafted separately using a combination of moulds and some manual detailing work. 9 As a result of this, each face is distinct, which leads many to incorrectly assume that the soldiers are representations of real people. This is untrue, however – on closer inspection one can establish eight facial types. In Kesner’s view the army represents an idealized cross-section of Chinese society. 10 However, this raises an important question: Why – when it would have been easy to simply mass produce the heads – are no two faces the same? ------- Essay ends here, notes below. Legalism, Meritocracy The answer to this in Chinese afterlife beliefs, and the meritocracy. When talking about idealism, mention the painting. 6 Ibid., p. 517 Man, The Terracotta Army, pp. 129-130 8 Ibid., p. 133 9 Ladislav Kesner, ‘Likeness of No-One (Re)presenting the First Emperor’s Army’ The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), p. 120 10 Ibid. 7 This can be done using an analysis of some of the dudes. Their faces and stuff. It was an authoritarian climate which de-emphasized the individual and class, focusing on what someone could do rather than who they were. but it also raises questions. Why were real weapons necessary? Why so many soldiers – or why were there not more? Power and Might, and Afterlife beliefs. P128 : Unification again It was the army itself which allowed unification by the first emperor. Since the next life reflects this one, unity must be maintained in the afterlife as well - hence the same army that unified china in life must unify afterlife-china as well. The number of people in the army is very important. Spend a little bit of time analyzing what the numbers meant. It was believed that the Chinese afterlife is a reflection of this one. Seeing as it was the military might of Qin which allowed for the unification of China, it is fitting that Qin Shi Huang should have Jane Oconnor p19: The army faced east - where threats could come from. Conclusion The Terracotta Army is a triumph of organization and bureaucracy; one that would have been, if not impossible, at least very difficult and unwise to build during a time of war. Structure Intro Intro to the Political Climate Organization Introduction of Legalism and Standardization made this project possible. Peace Might The terracotta army is a symbol of the state’s might. Intended to accompany Zheng into the afterlife. Meritocracy Intro Brief mention of political climate. Point about how the very presence of the Terracotta army is a reflection of the political climate at the time. Mass Production Meritocracy Immortality? Not necessarily a political concern, but on page 88 it’s talked about how qin shi huang was constantly striving to live forever. The fact that the terracotta army represents a microcosm of the world could be an effort to bring the world with him when he died. (my opinion!) The tomb, after all, was being constructed since Zheng was 13. (In fact, before the warring states period ended. ) AHA, but in 112-114, we’re told that the tomb started and then stopped. In the wrong place, thwarted by lack of labour, lack of organization, planning etc. So after unificaiton, with the prospect of unlimited labour, Zheng looked at the mountain and was all “shit, I can do better than this.” His tomb and the terracotta army are definitely symbols of power, might, or status. They’re a reflection of what was possible with a unified china. P98-101 talks about chinese afterlife beliefs. The terracotta army is essentially a gigantic toy, a collection of spirit vessels. Bibliography Cai, Yong and Kiser, Edgar. ‘War and Bureaucratization in Qin China: Exploring an Anomalous Case.’ American Sociological Review, Vol. 68, No. 4 (Aug., 2003), pp. 511-539 Washington: American Sociological Association, 2003. Cotterell, Arthur. “The First Emperor of China” London: Macmillan London Limited, 1981. Cotterell, Maurice. “The Terracotta Warriors: The Secret Codes of the Emperor’s Army” London: Headline Book Publishing, 2003. Kesner, Ladislav. ‘Likeness of No One: (Re)presenting the First Emperor's Army.’ The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), pp. 115-132 New York: College Art Association, 1995. Man, John. “The Terracotta Army: China’s First Emperor and the Birth of a Nation” London: Bantam Press, 2007. O’Connor, Jane. “The Emperor’s Silent Army: Terracotta Warriors of Ancient China” New York: The Penguin Group, 2002.