Mixed - Emory University

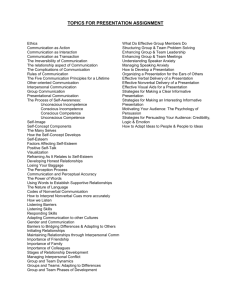

advertisement