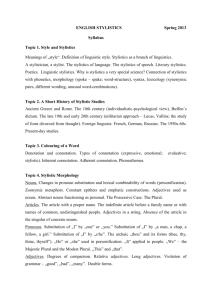

НОУ ВПО ИНСТИТУТ УПРАВЛЕНИЯ, БИЗНЕСА И ПРАВА И.В

advertisement