Words

advertisement

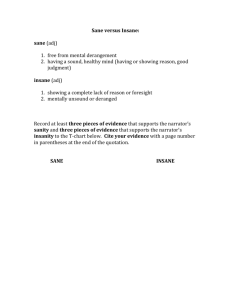

LAW EXTENSION COMMITTEE CRIMINAL LAW AND PROCEDURE THE DEFENCE OF AUTOMATISM; THE ISSUE OF INTOXICATION; AND THE ISSUE OF STATUTORY OFFENCES AUTOMATISM Defence of automatism goes to whether the conduct of the Defendant was voluntary. 2 Types of automatism 1. Insane Automatism (i.e. the defence of Insanity-the M’Naughten Rules; Porter (1933) 55 CLR 182). A disease of the mind, temporary or long standing, which prevents the defendant knowing the physical nature of the acts being performed; or knowing that what he or she was doing was wrong. Onus on the Defence to prove on the balance of probabilities. 2. Non Insane Automatism (i.e. the defence of Automatism) Prosecution bears onus of proving beyond a reasonable doubt that actions of Defendant were voluntary. If sufficient evidence to raise the defence of non insane automatism, Prosecution must disprove beyond a reasonable doubt. Bratty v A-G of Northern Ireland (1963) AC 386 (psychomotor epilepsy) Insane and Non Insane automatism are separate defences, but both can be put to the jury in appropriate circumstances. 1 Presumption that acts are voluntary, unless Defendant raises “sufficient evidence” of non insane automatism. External stimulus on a defective mental condition raises insanity, not non insane automatism. Radford (1985) 42 SASR 266 (dissociated state) If involuntary conduct is due exclusively to disease of the mind, applicable defence is insanity, not non insane automatism. Definition of disease of the mind is “underlying pathological infirmity of the mind” “Dissociated state” of Defendant was “the reaction of a sound mind to extraordinary stress produced by external factors” and raised non insane automatism. Trial judge erred by not allowing both defences of insanity and automatism to be considered by the jury. Falconer (1990) 171 CLR 30 (dissociated state/disorder) Mason C.J. Brennan and McHugh JJ Presumption should be that when Defendant raises a defence based on unsoundness of the mind, he or she raises the defence of insanity unless there are the following “exempting factors” which make insane automatism non insane automatism: 1. Transient; 2 2. Caused by trauma, whether physical or psychological, which the mind of an ordinary person would not have been able to withstand; 3. Not prone to recur. Defence bears onus of proving both insane and non insane automatism on balance of probabilities (majority disagreed that Defendant should bear onus of proving the defence of automatism). Toohey J (Deane J, Dawson J and Gaudron J agreeing in separate judgements) Instructions to be given to jury when evidence of insane and non insane automatism If non inane automatism raised, Prosecution bears the onus of disproving beyond a reasonable doubt. Adopts the test of Radford. Distinction between “disease of the mind” (insanity) and reaction of a sound mind to external stimuli. The importance of mental condition being prone to recur: Woodbridge [2010] NSWCCA 185 per Davies J (with whom McClellan CJ at CL and Hulme J agreed at [92]-[93] : “These passages make clear that the expression “disease of the mind is not to be narrowly construed and is not restricted to the psychotic disturbances of which Dr Quadrio spoke. The expression encompasses a temporary mental disorder or disturbance prone to recur. The dichotomy is not between a mind affected by psychotic disturbances and a mind affected by less serious ailments, but between those minds which are health and those suffering from an underlying pathological infirmity. 3 Once that is recognised, the basis that both Doctors identified as the cause of any automatism which the appellant suffered viz a dissociative disorder that had recurred on a number of occasions (and which was capable of leading to the extensive period of automatism which Dr Quadrio spoke) seems to lead inevitably to the conclusion that the appellant had a disease of the mind. Her mind was unsound rather than sound, and any automatism was insane rather than sane.” INTOXICATION Common Law position England DPP v Majewski (1976) 2 All ER 142 Self induced intoxication is relevant to crimes of “specific intent” (where the mens rea of the crime extends to intention/recklessness to bring about the consequences of an act), but not crimes of “basic intent” (where the mens rea of the crime is merely the intention/recklessness to perform an act). Australia O’Connor (1980) 29 ALR 449 No distinction between crimes of basic intent and specific intent. Self induced intoxication is relevant to both actus reus and mens rea of all crimes. Barwick CJ analysed in detail the relationship between intoxication; voluntariness; intention; and recklessness. 4 NSW Statutory Position (Part 11A Crimes Act)-When can intoxication be considered? Part 11A of Crimes Act introduced in 1996 (Sections 428A to 428I) to enshrine distinction between self induced intoxication in respect of crimes of specific intent (where self-induced intoxication can be taken into account in respect of mens rea) and crimes of basic intent (where self-induced intoxication cannot be taken into account in respect of mens rea). Crimes of specific intent listed in Section 428B (murder, assault with intent to have sexual intercourse, obtaining property by false pretences etc). Crime of specific intent defined in Section 428B “an offence which an intention to cause a specific result is an element”. Self induced intoxication CANNOT be taken into account for ANY CRIME in respect of whether the action of the Defendant was voluntary (Section 428G (1)). Non self induced intoxication (e.g. drink spiked by another) can be taken into account in respect of whether the actions of the Defendant were voluntary (Section 428G (2)) Self-induced intoxication CAN be taken into account in respect of the mens rea of offences of specific intent (unless became intoxicated to strengthen resolve to commit offence), but CANNOT be taken into account for the mens rea of other offences. (Section 428C) The defence of insanity and the issue of self-induced intoxication: Derbin [2000] NSWCCA 361, STATUTORY OFFENCES OF STRICT LIABILITY AND DEFENCE OF HONEST AND REASONABLE MISTAKE OF FACT 3 types of offences: 5 Requires proof of mens rea. Presumption is that offence requires proof of mens rea, unless displaced by the words of the statute. Absolute liability (only requires actus reus, and no defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact) Strict liability (defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact applies) He Kaw Teh (1985) 60 ALR 449 (importing drugs) Test of statutory interpretation as to whether statutory offence requires proof of mens rea, is absolute liability, or strict liability. Indicia include: Words of the statute Subject matter of the statute Will putting D under strict liability assist in the enforcement of the regulations Potential consequences for D if convicted. Jiminez (1992) 106 ALR 162 (dangerous driving occasioning death) Offence is one of strict liability, and defence of honest and reasonable mistake of fact applies Time whether driver’s mistake was honest and reasonable is just before he or she fell asleep. What is the evidence of tiredness? 6 Allen v United Carpet Mills Pty Limited (1989) VR 323 (environmental pollution) After applying test in He Kaw Teh Court found that offence was one of absolute liability. In respect of offences of strict liability, major defence is the defence of ‘honest and reasonable mistake of fact’, known as the Proudman v Dayman defence. Mayer v Marchant (1973) 5 SASR 567 Acts of a stranger over which D has no control is a defence to offences of strict liability. The distinction between mistakes of law and mistakes of fact: Ostrowski v Palmer (2003) 219 CLR 493. 7