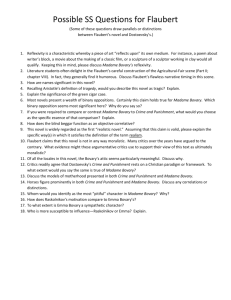

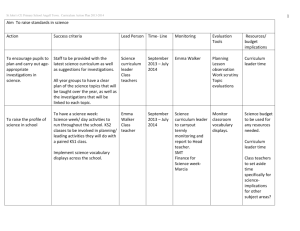

Madame Bovary Study Questions

advertisement

Madame Bovary Study Questions

1. How do you react to the main characters in the book? Do you admire or detest any of

them? Do you find any hateful, laughable or pitiable? Can you locate any heroes or

villains, good or bad characters?

2. How does the point of view in the novel work, and how does it affect your impressions

of the main characters? Pick a passage in which you find the point of view striking, and

analyze why it interests you.

3. How would you describe the tone of the book? Does it change?’

4. Emma has been called a "hopeless romantic." How and why does she become this kind

of person? What was Emma's education like? If Emma is corrupted by reading novels,

how does Flaubert deal with the fact that he is himself a novelist?

Would Emma's life be the same if she hadn't been sent to a convent school? How is

religion presented in the novel? How does Flaubert relate religion to Emma's

romanticism?

Is Emma ever happy? What does or would it take to satisfy her? Is anyone to blame for

her discontent?

5. How does socio-economic class figure in Bovary? How would a Marxist analyze the

book?

6. How are gender issues relevant to the novel? To be more specific (and to point this

question in only one out of many possible directions): the novel, written by a man, treats

a female protagonist. Do you think this has any effect on the portrayal of Emma?

Compare and contrast Pride and Prejudice along this axis. What would you say to a critic

who claims that Flaubert hates women?

7. Flaubert famously declared his identification with his protagonist with the words,

"Emma Bovary, c'est moi" ["Madame Bovary is me"]. What do you think he meant by

this? Does he show any affinity for Emma or similarity with her, as a writer or a man?

More broadly, are Emma's problems ones that a man can identify with, or are they

gender-specific?

8. Emma's reading of romances has a contemporary equivalent: the market for Harlequin

romances or soap operas. Who consumes these stories, and what is the appeal of the

stories for their audiences?

Flaubert, Gustave

Gustave Flaubert (1821-80) remains one of the most

important French novelists of the nineteenth century. Although he is most

often associated with the realist and naturalist movements because of his

desire for authorial objectivity, his works are not so easily classified. His

masterpiece, Madame Bovary (1857), is indeed a stylistic exercise in which

Flaubert attempted to eliminate all authorial visibility, yet the novel

manifests the influence of virtually all of the various literary movements of

the period, most notably the Romanticism whose "feminine phrases"

Flaubert professed to despise (Correspondance 1:210). Instead, he

advocates a doctrine of impersonality, which he sees as "the sign of

Strength" (2:466). Unlike the Romantics, who sought to continually

redefine the inner self, Flaubert aspired to a "grasp of the non-self and a

representation of the world" (Poulet 15). Flaubert's vision of the world is,

then, one that grows out of the Romantic tradition and is modified by his

fundamental desire to let the text speak for itself.

Flaubert was born in Rouen, where his father was chief of

surgery at the city hospital. It was in his youth in this provincial city that

Flaubert developed his hatred of all that was "bourgeois," an appellation

that had less to do with social class than with a limited, empty, bigoted

view of the world. After studying law briefly in Paris, Flaubert was stricken

in 1844 by the first of many nervous attacks that allowed him to withdraw

from public life and devote himself to his writing. He had by that point

formulated a rather pessimistic view of life, and thus his retreat from

society caused him no great hardship. He spent the rest of his life in

Croisset, outside Rouen, writing some of the most remarkable novels of his

time: L'Éducation sentimentale (1846), La Tentation de Saint Antoine

(1848), Madame Bovary (1857), Salammbô (1872), later versions of

L'Éducation sentimentale (1869) and La Tentation de Saint Antoine (1874),

and the unfinished Bouvard et Pécuchet. In addition, his Trois contes

(1877) includes the celebrated short story "Un Coeur simple."

Although Flaubert left no definitive statement on literary

theory, his correspondence allows us a view of the development of his

aesthetic that might not be possible in a theoretical text. Through the late

1840s and early 1850s he wrote regularly of his attempts to depersonalize

his works, championing "Form" as the only way to find "Truth" and "the

Idea" (Correspondance 2:91). When he set out to write his "book about

nothing" (2:31), Madame Bovary, he intended to eliminate all external

elements, leaving nothing but style itself. The foundation of this aesthetic

rests on his well-known declaration: "An author in his book must be like

God in the universe, present everywhere and visible nowhere" (2:204). The

more visible the author, the weaker the work.

Art, according to Flaubert, was moving toward a purity in

which the subject would be virtually invisible, leaving style free to be an

absolute "manner of seeing things" (2:229). Over the centuries, form had

become freer, leaving behind all rule and measure. The epic had given way

to the novel, poetry to prose. There was no longer any orthodoxy, and form

was as free as the will of its creator. It is not surprising that Flaubert is seen

by some as a precursor of the French "new novel" of the 1950s and that we

have seen the publication of a collection of essays entitled Flaubert and

Postmodernism. It could be argued, however, that his novels do not follow

the precepts he espoused and should not be called postmodern works.

In 1856, after five years of work during which he expressed

his desire to write a "book about nothing," Flaubert finished Madame

Bovary. While the novel is certainly a monument to style, Flaubert realized

that his aspirations toward complete impersonality were unrealistic. "I have

always sinned that way; I have always put myself into everything that I

have written" (Correspondance 2:127). At times during the writing of

Madame Bovary, he became so emotionally involved in his heroine's fate

that he fell ill. This novel about a young, romantic woman trapped in the

despised "bourgeois" world not only spoke of Flaubert's romantic side but

aroused enough passion in society to have the book brought to trial on

morals charges.

Flaubert reinforced the realistic vision he attempted to create

by his ingenious use of the style indirect libre, a stylistic device that

enabled him to express a character's thoughts or words without directly

identifying their source (of the many renderings of the term style indirect

libre, two of the most common are "free indirect style" and "represented

discourse" [Porter 1]). The first person is avoided, no quotation marks are

used, and no verb tells us that the character is thinking or speaking. Only

through context and style do we see that the objective narrator has turned

the text over to the character for the moment.

Flaubert alternates the supposed objective account of the third person

narrator's voice with the subjective experience of a character moving

through the world. The former is presented as a given that is in itself

unproblematic for narrator and reader; the latter involves an individual's

perception and misperception. The gap between the two gives rise to the

familiar Flaubertian irony. (D. Porter 374)

This irony helped bring Flaubert a measure of critical acceptance during his

lifetime.

Flaubertian criticism has varied widely over the years but

can generally be broken down into three overlapping stages. Traditionally,

Flaubert was seen as a realist; then, as criticism became more thematic, he

was considered an idealist; and finally, structuralist and poststructuralist

criticism have judged him to be an "indeterminist, a writer who resists

conclusions" (Porter 2). Overriding mere, and sometimes simplistic,

classifications is Flaubert's influence on writers of his time and on those

who came after him. His unswerving search for the mot juste "called into

question the notion that made literature a communication between author

and reader" (Culler 13). Without the reassuring guidance of an ever-present

narrator/author, the reader was presented with a new challenge. Authors of

the last hundred years have continued Flaubert's legacy by giving the reader

ever more leeway with which to interpret a work of fiction.

William VanderWolk

Flaubert is associated with the naturalist school, artists who described events with medical

precision. Indeed, Flaubert's father was a country surgeon and the writer trained briefly under

him. In his letters, Flaubert described literature as "the dissection of a beautiful woman with her

guts in her face, her leg skinned, and half a burned-out cigar lying on her foot."

This combination of medical detail and sexual violence summarizes Flaubert's style. He writes

neither in the third person, nor the first, but in the odd voice the French call "style indirect libre."

Events are recorded as if from the viewpoint of a particular character but not in that character's

voice. Flaubert retains a distance that evokes objectivity but also seems disdainful. His characters

all seem ridiculous. When Boulanger seduces Emma, for example, they are at a country fair and

he whispers above the sound of a farm wife winning an award for her pig. Emma's ideals of love

are no more exemplary than the woman's ideal of pig meat.

Study Questions: Flaubert, Madame Bovary

1. Why begin and end with Charles? How does this place Emma in perspective?

2. Watch for descriptions of eyes, sight, lack of sight; describe how these passages

contribute to characterization.

**3. Characterize the atmosphere of Tostes and Yonville; how does the environment here

shape individual lives? how do Emma and Charles react to these environments?

**4. Which characters are treated sympathetically? how does this treatment illuminate

Flaubert's moral sense?

**5. How does Emma define love? Charles? What passages illustrate their view?

**6. Find three passages spread over the first 75 pages that illustrate Flaubert as a master

of realistic detail at work. Explain and defend your choices.

7. What points of view are used in the narrative? how do these affect your involvement?

**8. Describe how Flaubert portrays basic bourgeois behavior and attitudes. How do

these compare with the aristocrats; does either group come out ahead?

9. Watch for times when Emma stands at a window; what need does this behavior seem

to reflect?

10. Images of machines reappear at intervals; what ideas do these images call up?

**11. Reflect on how money, materialism, economic issues are used to comment on

bourgeois society, and specifically the Bovary family.

12. Discuss how Emma's fascination with romantic (and Romantic) ideals affects her life.

13. Characterize Emma's attitudes towards Charles, Leon, Rodolphe.

14. After this novel was published, Flaubert was brought to trial on charges of

immorality; if you were a member of the jury, what would you decide?

15. Is Emma's fate tragic? is the novel tragic? why or why not?

2. How does nature imagery contribute to Flaubert's portrait of the relationship between Emma

and Rodolphe?

3. Emma's love for Rodolphe is adulterous; she is a married woman. How does the fact that she

is married (and the nature of her relationship with her husband -- briefly glimpsed on p. 93)

affect her experience of love?

1. Emma Bovary as a failed romantic: according to this view, blame lies largely with

Emma herself. Her dreams lead her down the wrong path.

2. Emma as a victim of bourgeois society: Emma is constrained by the world she lives

in. She is a tragic but heroic figure because she refuses to be limited by the role

society would have her play.

2. Emma as a woman in a patriarchal society: There are double standards for the

behavior of men and women. Essentially both of Emma's lovers act as she does

in throwing over the formal rules of society, but while the men are free to go on

to the next escapade, Emma pays with her life simply because she is a woman,

and women do not have the freedom of men.

Write a one page typewritten character analysis. You may choose one of the

following characters: Charles, Homais, Rodolphe, Leon or Lheureux. Draw your

analysis from the different "schools" of literary criticism (i.e. New Historicist,

Cultural Materialism, Feminism, and/or psychoanalytic). We will use these as the

basis of our discussion

free indirect style (or free indirect discourse). A manner of presenting

the thoughts or utterances of a fictional character as if from that character's

point of view by combining grammatical and other features of the character's

'direct speech' with features of the narrator's 'indirect' report. Direct discourse

is used in the sentence She thought, 'I will stay here tomorrow', while the

equivalent in indirect discourse would be She thought that she would stay

there the next day. Free indirect style, however combines the person and tense

of indirect discourse ('she would stay') with the indications of time and place

appropriate to direct discourse ('here tomorrow'), to form a different kind of

sentence: She would stay here tomorrow. This form of statement allows a

third-person narrative to exploit a first person point of view, often with a

subtle effect of irony, as in the novels of Jane Austen. Since Flaubert's

celebrated use of this technique (known in French as le style indirect libre) in

his novel Madame Bovary ( 1857), it has been widely adopted in modern

fiction. [Chris Baldick, 1990]

Example:

Across the way, beyond the roofs, the broad, pure sky stretched out, the red sun setting. How

nice it must be over there! How cool under the hedgerow! And he opened his nostrils to breath

in the sweat fragrances of the countryside, which didn’t waft their way all the way up to him.

People were watching them [dance]. They glided by and glided back, she, her body immobile

and her chin down; he, always in the same position, his back arched, his elbow bent, his chin

jutting forward. She knew how to waltz, that one! They continued for a long time and tired

everyone else out.

Adapted from Gustave Flaubert Madame Bovary

Flaubert’s use of free indirect discourse is related to his desire to remove himself (the author)

from his work, creating uncertainty and various possibilities for interpretation. For example,

When Flaubert writes of Emma that "She found in adultery all the platitudes of marriage" it is

unclear whether this is Emma’s opinion, or Flaubert's, or even perhaps the reader’s. Indeed, we

know that after the trial of Madame Bovary for immorality Flaubert was forced, by the very

keenly pro-family Second Empire court to change that particular sentence from "the platitudes of

marriage" to "the platitudes of her marriage". The necessary, and in Sartre's view ethically

positive, demoralisation of the bourgeois reader depends at least in part on precisely this

uncertainty as to authorial intention. Flaubert is a committed writer paradoxically because he

refuses to tell us what he thinks. Style indirect libre (free indirect discourse) and similar

experimental narrative devices are the key to the commitment of a writer whose personal

reactionary misanthropy sets up an intriguing counterpoint to Sartre's compelling reading of his

work.

Like Genet, Flaubert proposes a trap to his bourgeois reader. A tale of provincial adultery, a

moral tale where the sinner comes to a bad end, a story which appeals to the mid-nineteenthcentury reader's desire to blame fate for all evil and mishaps - "the worst is always certain",

"destiny is to blame" - in fact masks an insidious nihilism, a disturbing disruption of the common

categories of intention, responsibility, viewpoint. Narrative devices of perspectival dislocation

run counter to the apparent story-line. What Flaubert's novel reveals through the appeal of the

sensuous lyricism it celebrates, is the worm at the heart of being, the inability to distinguish real

from imaginary, totality from nothingness. It is self-nihilating and demoralising, its surface

subject matter is a pretext for an insidious luring of the reader towards perceptual and ontological

insecurity and ultimately nihilism.

Gustave Flaubert's Madame Bovary

Background

Gustave Flaubert was born in 1821 in the provincial capital of Rouen, France, where he lived

most of his life and died in 1880. The son of a provincial doctor, Flaubert was encouraged to go

into law. During his studies he had what we might term a breakdown. Afterwards, he decided to

become a writer. He began with Romantic musings and travel writing about his trip to the Near

East, all of which went unpublished. He did not publish Madame Bovary, his first novel, until he

was thirty-five. It was originally published as a serial in the magazine Revue de Paris, which led

to a celebrated trial in which Flaubert was charged with "offenses against public morality" for

what was seen as the scandalous nature of the tale of a discontented middle-class housewife and

her love affairs. He was acquitted, and the novel was published with the subtitle Moeurs de

Province (Provincial Mores). In a review, the noted novelist Honoré de Balzac claimed Flaubert

had revived the stagnant form of the novel in France. Flaubert sought to portray the utter

bleakness of lower middle-class provincial life and the bourgeoisie he despised. His success in

this goal derived from his juxtaposition of detailed descriptions of every aspect of his subject

(provincial life) against the romantic fantasies and desires of the protagonist, Emma Bovary.

Madame Bovary is set during the "July Monarchy" of King Louis-Philippe, who was brought to

power during the Revolution of 1830 and ousted during the Revolution of 1848 (the novel begins

with Charles Bovary's schooldays in 1827 and ends with his death in 1846). The July Monarchy

was known as the "bourgeois monarchy" because Louis-Philippe embraced middle-class values

and advised his subjects to "get rich!" Aspects of life during the July Monarchy are clearly

evident throughout Madame Bovary, especially class differences, anti-clericalism, and concerns

of economy. While Flaubert mocks all of these, he most directly challenges the moral standards

and domesticity of the bourgeoisie.

Making the main character a woman gave an added dimension of limitation and restriction to the

story. Women in nineteenth-century France could not vote; indeed, they were not citizens of the

nation and were considered minors and under the guardianship of either their fathers or their

husbands. Married women could not own property or engage in any kind of business except

through their husbands. Thus, Emma Bovary's romantic, self-fancied aristocratic spirit is kept

from the passionate life she desires by both her class and her gender.

Characters

Emma Bovary

The protagonist of the novel. Daughter of a farmer, educated at a convent, Emma's fantasy life

and her affairs make her a problematic protagonist, since she is often unsympathetic; but the

reader can easily sympathize with the limits of her situation as the wife of a small-town country

medical officer.

Charles Bovary

Emma's husband. Small-town, low-level doctor who loves his wife dearly and even moves to a

new town, despite the blow to his practice, in an attempt to make her happier. Her constantly

changing moods and erratic character do not deter his love, but only make him more concerned

about her.

Monsieur Charles-Denis-Bartholomé Bovary

Charles's father. A surgeon's aide in the army before a scandal forced him to leave the service.

With his good looks he managed to find a knit-goods dealer's daughter with a lot of money to

marry. Never an attentive husband, he was also idle in his work and changed jobs several times

before eventually retiring to the country.

the older Madame Bovary Charles's mother and Emma's mother-in-law. A knit-goods dealer's daughter, she was lively and

very much in love with the elder Monsieur Bovary when they met; his inattentive nature,

however, turned her into an unpleasant, fault-finding older woman. She is consistently resentful

of Charles's affection for Emma, whom she criticizes at every opportunity.

Heloïse Dubuc

A forty-five year old widow who was Charles's first wife.

Monsieur Rouault

Emma's father. A farmer who has no will to work and a great taste for the comforts of life. He is

not as well-off as people think.

Berthe Bovary

Daughter of Emma and Charles Bovary.

The marquis d'Anderville

A local noble who invites Charles and Emma to a ball at his palace when they live in Tostes.

The Vicomte

An aristocratic guest at the ball who dances with Emma, and whose reappearance through the

novel symbolizes Emma's desire for a different life.

Monsieur Homais

The pharmacist in Yonville; friend of the Bovarys. He is ambitious and cunning, and runs a local

newspaper that largely serves him and his friends. Homais's strident political opinions had

alienated one respectable person in town after another. His values (anticlericalism,

republicanism) and way of life (intense capitalism, sneaking around government rules) are

representative of the middle-class bourgeoisie, and his particular manifestation of them are

presented as simultaneously evil and simple-minded.

Madame Homais

Monsieur Homais's wife.

Monsieur Léon Dupuis

A clerk to the notary in Yonville. He shares a friendship with Emma, who he loves deeply. He

leaves to study law in Paris. When he returns to the region (he moves to Rouen, the largest town)

their friendship turns into a love affair.

Madame Lefrançois

Proprietor of the l'Hôtel Lion d'Or in Yonville.

Monsieur Bournisien

The local curé, or town priest.

Monsieur Lheureux

Shopkeeper and money-lender in Yonville. Flaubert plays on regional stereotypes in the

description of him as combining the "southern volubility" of his native Gascony with "the

cunning" of his long-time adopted region of Normandy. He encourages Emma to run up a debt

with him and betrays her by endorsing the notes to others when he had promised not to do so. He

represents the evils of excessive capitalism.

Monsieur Rodolphe Boulanger

Local wealthy landowner. After meeting Emma, he quickly seduces her. Although he has

feelings of love for her and often finds her irresistible, her sentimentality and position as his

mistress reminds him of other women he has known and when she pushes for him to take her

away from her life he leaves her, heartbroken.

Félicité

Bovary's maid.

Justin

Young assistant to Homais. He has a crush on both Felicité and Emma, eventually becomes

something of a lady's-maid to Emma (despite his gender). A constant source of disappointment

to Homais, who catches him reading a book on "conjugal love," among other indiscretions.

Monsieur Binet

The local tax collector.

Hippolyte

The stable boy at the hotel. He has a clubfoot that Charles, at the urging of Homais, tries to cure

with an operation.

Doctor Cavinet

Local doctor. Amputates Hippolyte's leg; is called to help Emma.

Doctor Larivière

Prominent doctor of the region. A confident, talented man who saves Hippolyte and Emma by

intervening where Charles Bovary had failed to help them. Believed to be based on Flaubert's

father. Monsieur Vinçart: Rouen banker to whom Monsieur Lheureux endorses Emma's debts.

Themes

Madame Bovary is an intensely detailed portrayal of the cheerless banality of lower middle-class

life in the French provinces in the middle of the nineteenth century, and the most "realistic"

novels of its period. By setting a sublimely Romantic character, such as Emma Bovary, in the

middle of this life, Flaubert highlighted its limitations. He also married realism and

Romanticism. While Madame Bovary is very much of the naturalist school of literature in the

way it details its subjects so precisely, it combines that style with poeticism and Romanticism

through Emma's aspirations and the consistent melding of human emotion with nature through

metaphor.

Although this quality if not evident in English translations, Madame Bovary is famous for the

intensely rhythmic and mellifluent style of its prose. The original French reads flat and stark,

despite its artistically crafted details, engrossing the reader with its almost monotonous tone.

Flaubert masterfully portrays the dreariness of the lives he explicates with this smooth, effluent

writing style. He details every element of the world depicted in the novel, no matter how

mundane. This depiction is engaging and successful due to what he called a style indirect libre

(free indirect discourse) which was neither first nor third person, but rather flowed between the

two.

A central theme in Madame Bovary is the disjuncture between reality and perception, between

society and desire. Sometimes this is shown through the difference between what a character

wishes were true and what is actually happening, as when Charles attributes Emma's

unhappiness in Tostes to the air and environment of the town instead of her deep dissatisfaction

with married life; other times it is shown in Emma's reflection on her feelings, as when she

grows to hate Charles more and more, and yet she knows it had little to do with him and more to

do with her love for another man.

Equally important is the theme of the bourgeoisie, particularly their shortcomings. Flaubert

deeply detested bourgeois values-the propriety, the economy, the hypocrisy of morals, the smallmindedness, the ridiculous religious clinging to anticlericalism-and this comes through loud and

clear throughout the novel. In many ways, Emma can be seen as the victim of the bourgeoisie,

whose standards and petty ways trapped her in a life without imagination and without passion.

Yet her spirit leads her to live a life that seeks passion and pleasure despite the rules she is

expected to follow; when it comes time to confront this dichotomy, she chooses to kill herself

rather than face the shame that would necessarily ruin her life.

In his essay "Realism and the Contemporary Novel" (1961) Raymond Williams describes

realism as "a touchstone, for it shows, in detail, that vital interpenetration, idea into feeling,

person into community, change into settlement, which we need, as growing points, in our own

divided time. In the highest realism, society is seen in fundamentally personal terms, and

persons, through relationships, in fundamentally social terms" (590). Throughout the essay,

Williams describes realism as an interest in society and interaction. How does Madame Bovary

reflect these realist values? How does Flaubert assert the importance of social terms? Provide a

close reading of a chapter or scene in the text to support your argument. (Chapter 8, the

agricultural fair, offers a good example of the interplay between personal and social worlds)

The three novelists use images of confinement to suggest that characters feel trapped by a society

that controls them without understanding them

1. Emma’s inner life is based on pretense, but pretense also seems to surround her in the

real world. The first part of the novel is replete with models of mediocrity pretending to

be refined and aristocratic, but in fact bordering on the ridiculous. Describe how Emma

and Charles’ wedding and the character Homais exemplify pretense and provide an

appropriate backdrop for Emma’s own behavior.

2. Explore the different roles Emma "tries on" as a wife, lover, mother, and saint Why does

she fail to find fulfillment no matter what she chooses? In essence, what is her tragic

flaw?

3. Throughout the various experiments, does Emma ever evince any inner conflict over her

behavior? If so, please cite examples. If not, does her naiveté cause you to sympathize

with her more?

1994: In some works of literature, a character who appears briefly, or who does not appear at all,

is a significant presence. Choose a novel or play of literary merit and write an essay in which you

show how such a character affects action, theme, or the development of other characters. Avoid

plot summary.

1995: Writers often highlight the values of a culture or a society by using characters who are

alienated from that culture or society because of gender, race, class, or creed. Choose a play or a

novel in which such a character plays a significant role and show how that character's alienation

reveals the surrounding society's assumptions and moral values.

The British novelist Fay Weldon offers this observation about happy endings: "The writers, I do

believe, who get the best and most lasting response from readers are the writers who offer a

happy ending through moral development. By a happy ending, I do not mean mere fortunate

events…a marriage or a last-minute rescue from death…but some kind of spiritual reassessment

or moral reconciliation, even with the self, even at death." Choose a novel or play that has the

kind of ending Weldon describes. In a well-written essay, identify the "spiritual reassessment or

moral reconciliation" evident in the ending and explain its significance in the work as a whole.

Avoid mere plot summary.

Novels and plays often include scenes of weddings, funerals, parties, and other social occasions.

Such scenes may reveal the values of the characters and the society in which they live. In a

essay, discuss such a scene from Madame Bovary and show how the scene contributes to the

meaning of the work as a whole. Avoid mere plot summary.

“The experienced reader evaluates an ending not by whether it is happy or unhappy, but by

whether it is convincing. In other words, he wants the ending to follow logically from the nature

of the characters and from the preceding action.”

Write a well-developed essay in which you consider Madame Bovary in light of this statement.

Avoid mere plot summary.