TIME MAGAZINE,Snyder Article.doc

advertisement

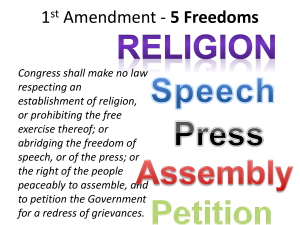

TIME MAGAZINE/CNN Wednesday, Oct. 06, 2010 Inside the Supreme Court's Free-Speech Showdown By Sean Gregory / Washington "Is this a joke?" a befuddled young woman asked as she stood outside the Supreme Court on the morning of Oct. 6. She was staring at members of the Kansasbased Westboro Baptist Church, who were wearing sweatshirts emblazoned with the church's website, godhatesfags.com. A 9-year-old boy, a grandson of Westboro founder Fred Phelps, stood as tall as his tiny body allowed, holding a "God Hates You" sign. But these churchgoers, who believe all Americans are hellbound because of the country's tolerance for gays, weren't just shouting about the evils of homosexuality. They were also demeaning Jews — because Jews killed Jesus, don't you know? — and calling Catholic churches dog kennels because, as one Westboro member explained, priests are gay and molest children. Westboro members have carried out hate-filled demonstrations like this one every day for the past 19 years, staging their protests outside places like high school plays and military funerals. On Oct. 6, they assembled in front of the Supreme Court as it prepared to hear oral arguments in the case of Snyder v. Phelps, which pits the grieving father of a Marine killed in Iraq against Westboro, a 70-member congregation in Topeka that consists almost entirely of Fred Phelps' extended family. In March 2006, seven Westboro members picketed the Maryland funeral of Lance Corporal Matthew Snyder, who died when his humvee crashed in Iraq. The Westboro protesters flew more than 1,000 miles so they could hold signs with messages like "Thank God for Dead Soldiers," "You're Going to Hell" and "Thank God for IEDs." Matthew's father Albert Snyder, citing the physical and mental trauma that resulted from being confronted by the group at his only son's funeral, filed a lawsuit against Westboro. A jury found the church liable for intentional infliction of emotional distress, invasion of privacy and civil conspiracy, and awarded Albert $10.9 million in damages (which the trial judge later reduced to $5 million). The Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, however, reversed the verdict, ruling that the First Amendment protected Westboro's speech. The emotionally charged case, which raises questions about when public commentary becomes personal harassment and whether there should be limits on freedom of speech at the funerals of private citizens, has received more attention than any other before the Supreme Court this term. The line to get one of the coveted seats inside the court that are reserved for the public snaked around the block toward Independence Avenue. "I got a golden ticket," bragged David Overhuls, a second-year student at Georgetown Law School who had camped out overnight for the hearing; when he arrived at 10 p.m., about 40 people were already waiting in line. Some had arrived on Monday, Oct. 4. In the run-up to the oral arguments, eager college kids and law students argued over the details of the case with several members of the Phelps family (the 9-yearold not included). The discourse was civil — for the most part. "Appellate courts get s____ wrong all the time," Overhuls shouted during one of the more heated exchanges. When one of the Phelpses paused to check a text message, a student mocked him, saying, "God hates cell phones." Meanwhile, Sam Garrett, a freshman at George Washington, stripped down to his underwear and held a sign of his own: "Fred Phelps Wishes He Were Hot like Me." Garrett, who is gay, sashayed over to where the Phelpses were assembled, to the delight of the youthful crowd. Inside the courtroom, it didn't take long for the Justices to start picking apart the arguments. "We are talking about a funeral," Albert Snyder's lawyer Sean Summers began in his opening remarks. "If context is ever going to matter, it has to matter in the context of a funeral." Then Justice Antonin Scalia interrupted, asking, "Are we just talking about a funeral? That's one of the problems I have with the case." Legal analysts had predicted that some of the facts surrounding the case would give Scalia trouble. They were spot-on. The Justice pointed out that Albert based his emotionaldistress claim in part on offensive words that Westboro published about the Snyder family on the Internet about a month after the funeral. "What does that have to do with a funeral?" Scalia asked. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg challenged Albert's claim of invasion of privacy. She pointed out that even under Maryland's funeral-picketing statute, which was passed after Matthew's funeral, the Phelpses weren't breaking any laws. They had checked with police on how far away from the church they should stand, and they left around the time the funeral began. Scalia followed up by noting that the Snyder family had rerouted the funeral procession to avoid seeing the protesters. "Is that the extent of the disruption?" Scalia asked incredulously. Summers responded by saying that since Westboro "took away the peaceful experience" of a private figure, the rerouting had invaded Albert's privacy. Later, however, Scalia challenged Fred Phelps' daughter Margie Phelps, an attorney representing Westboro before the court. The Justice questioned whether Westboro's hate speech should qualify as "fighting words," which are not protected by the First Amendment, and wondered why Albert shouldn't be entitled to an emotional-distress claim, since he had suffered physical injury. (At the trial, Albert's doctors testified that the stress caused by Westboro at his son's funeral had worsened his diabetes.) (Comment on this story.) But it was Ginsburg who asked Margie perhaps the biggest zinger of the day: "Why should the First Amendment tolerate exploiting this bereaved family when you have so many other forums for getting across your message?" Ginsburg noted that the same day the Phelpses picketed Matthew's funeral, they had also protested at the state capitol in Annapolis. speech.) During the arguments, Margie appeared more confident, and less stammering, than her opponent. But she seemed to bother the Justices by insisting that Albert was a public figure and thus a less-protected target of offensive speech. Albert had attained public status, Margie argued, since he spoke to the media about Matthew's death before the funeral and since he published the time and location of the service in local newspapers. It was a strange strategy, particularly since the appellate court had ruled that Westboro's speech received First Amendment protection — regardless of whether it was directed toward a public or private figure — as it was hyperbolic and couldn't be proved false. A few Justices indicated that they might want to take on the larger First Amendment questions that stem from Snyder v. Phelps. For example, after establishing that Albert had seen the offensive content of the signs on television and the Internet, rather than during the funeral, Justice Stephen Breyer raised two questions. "One is, Under what circumstances can a group of people broadcast on television something about a private individual that's very obnoxious?" he said. "And the second is, To what extent can they put that on the Internet, where the victim is likely to see it? Now, those are the two questions that I am very bothered about. I don't know what the rules ought to be there." These questions may help explain why so many news organizations signed an amicus brief supporting Westboro's right to free speech. Was Breyer suggesting that the media could be complicit for having broadcast the hate speech? QUESTIONS 1. Who is the petitioner in the case? Who is the respondent? 2. In your opinion, what might be the important constitutional question at stake? 3. Identify two interesting points raised by the Supreme Court justices. Comment. PART II: Snyder v. Phelps Consider these precedent cases (stare decisis). Indicate whether the case can be use to support the petitioner, the respondent, or both. PRECEDENT CASE Schenck v. United States (1919) This case gave birth to the “clear and present danger” test In many places and in ordinary times, the Defendants in saying all that was said in the leaflets would have been within their constitutional rights. However, the character of every act depends on the circumstances in which it is done. The question in every case is whether the words are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to protect. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in a time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right. Cox v. Louisiana, (1965). It is axiomatic that “[t]he rights of free speech while fundamental in our democratic society, still do not mean that everyone with opinions or beliefsto express may address a group at any public place and at any time. The constitutional guarantee of liberty implies the existence of an organized society maintaining public order, without which liberty itself would be lost in the excesses of anarchy.” Thus, even in a public forum, expressions of opinion can be limited by “reasonable restrictions on the HOW COULD THIS HELP THE HOW COULD THIS HELP THE PETITIONER? RESPONDENT? time, place, or manner of [the] protected speech, provided the restrictions are ustified without reference to the content of the regulated speech, are narrowly tailored to serve significant governmental interests, and leave open ample alternative channels for communication of the information.” National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie (1977) After being asked for a large insurance bond to march in Chicago's southwest side, a neoNazi group led by Frank Collin, above, said it would march instead in a Jewish suburb where many Holocaust survivors lived. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, where the justices upheld the right of the NSPA to assemble while displaying swastikas. Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988) In a 1983 issue of the pornographic magazine published by Larry Flynt, above, a parody described a drunken sexual encounter in an outhouse between the famous evangelist Reverend Jerry Falwell and his mother. Falwell sued and was awarded $200,000 in damages by a lower court, but that decision was overturned in an 8-0 Supreme Court ruling that said that the parody was within the law, because no reasonable person would have interpreted it to contain factual claims. Frisby v. Shultz (1988) Did a Brookfield, Wisconsin ordinance that prohibits picketing in front of residences in the town violate the Constiution?. The Court decided that the First Amendment of the Constitution permits the government to prohibit offensive speech as intrusive when the captive audience cannot avoid the objectionable speech. The target of the focused picketing, banned by the ordinance is just such a captive, figuratively, and sometimes literally trapped into their home by the protesters. These individuals who object to the speech have no means of avoiding this unwanted speech. R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992) After a group of teenagers burned a crude cross on the lawn of an African American family in St. Paul, Minn., one of them, (whose full name was not released because he was a juvenile at the time) was convicted under a city ordinance aimed at bias-motivated crime. In a unanimous decision, the Supreme Court struck down the St. Paul ordinance, thereby overturning the conviction of the teenager. After looking the facts of this case, and considering the precedent cases, how would you decide on this case, and why?