In opening my paper, I want to acknowledge with respect the

1

ACWA 2002 Conference

‘What Works!? Evidence based practice in child & family services’

2 to 4 September 2002

Session 02

EXAMINING THE EVIDENCE IN OUT-OF-HOME CARE

What do we know about practice that works, given differences in valued outcomes of alternative approaches in child welfare, and different perspectives of a variety of stakeholders: children and young people; carers; birth parents; service providers?

Professor Ros Thorpe

School of Social Work and Community Welfare

James Cook University

In opening my paper, I want to acknowledge with respect the Dharawal people, the traditional owners of the land on which we’re meeting. This, I believe, is significant for our focus in this session in at least two ways: Firstly, in every State across Australia the experience of colonisation for Indigenous Australians is now recognised, at least in part, in child welfare policy through endorsement of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child placement principle

(SNAICC 2002). Secondly, my opening statement focuses our attention on respect as a key concept in child welfare practice, a theme to which I will return later in this paper.

My brief for presenting this paper is twofold: first, to focus on practitioners and stakeholders in the out-of-home care stream of child welfare practice; and second, to identify how, in our practice, we can make use of knowledge about what works well, in order to achieve desirable outcomes.

On the face of it, this sounds simple enough. However, in our post-modern reality it’s a rather more complex matter to identify appropriate knowledge that’s applicable in our particular local contexts

. Additionally, there’s the question of what counts as knowledge: for example, is research evidence to be privileged over practice wisdom and theory? And in this regard, the interplay of values and knowledge cannot be ignored, not least because we know there are disagreements among stakeholders, practitioners and researchers about what is a desirable outcome, and what are desirable means for achieving outcomes.

Since these complexities impact on the discussion in this paper, it’s vital that I make explicit from the outset the frame of reference which underpins the paper.

The framework for this paper.

Because I have an interest in cross-cultural perspectives in social welfare practice (see for example Lynn, Thorpe, Miles, Cutts, Butcher and Ford 1998), and because our current research in Mackay includes a focus on Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander and Australian South Sea

Islander foster care, I have actively searched for literature and analyses that are not entirely dominated by “western” thought. Of particular note is an international comparative study written this year by Shanti George and Nico van Oudenhoven (2002) for the International Foster

Care Organisation (IFCO).

2

George and van Oudenhoven (2002) consider children’s issues from a global perspective and provide examples from what they call the “low income, majority world”; examples which stimulate critical reflection about taken-for-granted assumptions in “western”, and especially

Anglo/American child welfare literature. Their starting point is the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), to which Australia is a signatory. In particular, they draw attention to Article 20 which asserts the child’s right to special protection and assistance from the state, including alternative care, if necessary.

Article 20 then proceeds to specify two principles to which due regard should be paid in providing alternative care:

desirability of continuity in a child’s upbringing

the child’s ethnic, religious, cultural and linguistic background

With the convention in mind, George and van Oudenhoven (2002) outline an International

Human Development Framework and it is this which I am taking as an explicit value base for considering what works in out-of-home care.

empowerment

full participation of all stakeholders

rigorous implementation of human rights, in particular the rights of the child

commitment to working with people under stress

validation and recognition of local practices

partnerships based on equality and mutual respect

Out-of-Home Care

In addressing the core focus of this paper, it’s useful to provide a brief overview of the range of options for the care of children and young people who are unable to live with their birth parent(s), either temporarily, indefinitely or permanently. George and van Oudenhoven (2002) usefully differentiate between informal, non-formal, and formal care arrangements and identify types of care in use around the world. These I have organised as follows, adding a couple of my own perspectives.

Informal and non-formal care

Birth family

Customary adoption (eg TSI and the Pacific region)

Informal (and non-formal) “social network” foster care

Blood relatives

Extended family

Cultural (or interest group) community

Friends

Neighbourhood

“Loose” foster care or contact networks

(for children/young people who fend for themselves)

Boarding schools

3

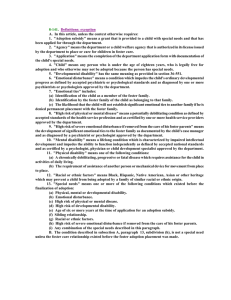

Formal care formalised (legal) adoption (by known adults or strangers) formal foster care:

options as for informal foster care

PLUS

Strangers beyond the neighbourhood

Residential care

Small/family group homes

Institutions

Boarding schools

Youth shelters/hostels

“Loose” foster care or contact networks

(for children/young people under formal care but fending for themselves)

Definitions

Informal care refers to arrangements which occur informally “at social cost” without mediation by formal or non-formal agencies.

Non-formal care refers to arrangements mediated by community based, religious or other nongovernment organisations, but at “social cost” and without the involvement of formal agencies

(for example, as mediated in Australia by Indigenous Shared Family Care agencies for children who have not come to the attention of formal child welfare authorities.)

Formal care refers to care arrangements authorised and financed (at least in a token way) by the state, most often (but not always) for children and young people who have been made wards of the state.

Adoption can be either legal or non-legal, as with customary adoption in the Pacific region, including the Torres Strait Islands and the islands from which Australian South Sea Islanders were blackbirded to Australia in the late nineteenth century.

Foster care refers to care within families. It can be informal, non-formal or formal.

Residential care refers to non-family based care. This is usually a formal form of care although the informal use of boarding schools should not be overlooked.

“Loose fostering” (a term coined by George and van Oudenhoven 2002) refers to the network of contacts which may be developed by street kids and young people who fend for themselves.

These can range from pseudo family settings, which may provide shelter and food (but in exchange for sex work or criminal activities), to occasional sources of support (eg leftovers from restaurants; permission to sleep in protected shop doorways).

4

In Australia we know very little about the extent and nature of informal and non-formal care, although it may be quite common, especially in Indigenous communities. For example, in our current study of foster care in the Mackay/Whitsunday region, I interviewed an Indigenous community elder who had fostered dozens of children over several decades, yet only one of these had been a formal arrangement, registered with the Queensland Department of Families, for which he had received a fostering allowance.

Most usually when we speak about out-of-home care in Australia, we have in mind formal care, authorised by government departments, and provided either directly or by non-government agencies under contract. We also know that at the current time in Australia the most common form of formal care is family based foster care: 88% Australia wide (Bath 1998); a staggering

97% in Queensland last year (QDOF 2002 p.4).

Other current facts, figures and concerns we should note are:

a small increase in the number of children entering formal care in Australia in recent years

(Sultmann and Testro 2001), including a continuing disproportionate, and in fact growing, number of Indigenous children (Dodson 1999; Neill 2002).

a decline in residential care placements around Australia (Bath 1997)

an increase in the need for foster care, consequent upon the previous two trends (Bath 1998)

an increase in the proportion of children in foster care with special or extraordinary needs resulting from the more challenging needs of children entering care, as well as the unavailability of residential options, which in previous times accommodated (and sometimes treated) those with extreme needs (Ainsworth 2001; Bath 1997).

a decrease in the general availability of foster placements, with a grave shortage of placements able to cope positively with challenging emotional and behavioural difficulties

(Wise 1999; Thorpe 2002).

an increase in the breakdown of placements for a variety of reasons (Delfabbro, Barber and

Cooper 2000;Thorpe 2002).

Concern about the effect of multiple placement changes and poor quality adult life outcomes for children in care (Fernandez, E 1996; Delfabbro, Barber and Cooper 2000; Cashmore and

Paxman 1996).

In identifying these features it is clear that Australia shares the current worldwide crisis concerning the availability and quality of foster care. Around the globe, a number of strategies have emerged, some of which are occurring here in Australia.

1.

A renewed focus on prevention through family support and family preservation services

(QDOF 2002 p.1).

2.

An emphasis on out-of-home care as a child protection measure, providing a service for children and families, with the goal of reunification (Sultmann and Testro 2001).

3.

An increase in the formal use of “social network foster care” (Portengen 2001, cited in

George and van Oudenhoven 2002), and in particular what is referred to in Australia as kinship care (Bath 1998; Ainsworth and Maluccio 1998).

4.

A move towards professionalising foster care, at least for some carers who are trained, supported and paid to provide treatment or therapeutic foster care for children and young people with especially challenging needs (George and van Oudenhoven 2002).

5.

The call (as yet not well heeded) for the limited re-establishment of residential facilities to provide for those unsuited to foster care and/or in need of very specialist treatment

(Whittaker 2000).

5

6.

A focus on providing children and young people with what is variously conceptualised as permanency, stability or continuity, through case planning, and a range of legal measures including, to a greater or lesser extent, adoption (Lowe and Murch 2002; Sultmann and

Testro 2001).

7.

A focus on planning to better meet the developmental and well being needs of children in care, and the transition of young people into adult life (Maluccio, Ainsworth and Thoburn

2000; Sultmann and Testro 2001).

It is in this context of possibly competing, but potentially complementary, strategies that practitioners and stakeholders in out-of-home care in Australia are grappling with the question:

What works!?

In addressing this issue, it’s impossible in a single paper to provide comprehensive coverage.

Accordingly, I’ve selected areas of particularly salient and current concern. In doing so, I recognise that I’m omitting certain areas of quite critical current importance in Australia; for example, the mandatory detention of unaccompanied and other child asylum seekers; the needs of children with disability in out-of-home care; the educational needs of children in care; the transition from care to independent adult living. I note, however, that other sessions in this

Conference will provide focus on these areas in far more detail that I could do here.

The areas on which I have chosen to focus, albeit necessarily briefly, are:

kinship care

foster care

permanency/stability/continuity planning, and the place of adoption

participation of children and young people

participation of birth parents and wider family.

In examining what we know from research evidence, practice wisdom, and theory, it’s important to bear in mind the issues that I identified at the very start of this paper relating to the applicability of knowledge, and debate concerning desirable outcomes and the means whereby they’re achieved. Additionally, I must emphasise that in assessing outcomes, it’s always necessary to weigh up strengths together with possible risks or limitations. For example, in achieving goals of safety, or of stability, for a child, aspects of well-being, such as cultural identity, may be compromised. Conversely, by safeguarding cultural identity (as advocated in the UN Convention) other goals of care may be less well enhanced.

Kinship Care - “social network foster care”

Consideration of what we know about kinship care (albeit largely from overseas) provides a good example of the importance of identifying benefits as well as concerns.

Benefits

care in own family/community/neighbourhood

cultural identity preserved

continuity of family and social relationships

placement with siblings

6

contact with birth parents

reduced trauma of separation, and of placement with strangers in a different environment

Concerns

less protection from abuse by birth parents or family members

increased length of stay in foster care (less reunification; less adoption out of care)

less formal support for kinship carers, who may be older, less healthy and in financial hardship

limited recognition and respect for kinship carers.

(George and van Oudenhoven 2002)

Increasingly in Australia kinship care is being used to both offset the shortage of foster placements and to achieve the benefits of “social network foster care” (Portengen 2001, cited in

George and van Oudenhoven 2002). In this regard, kinship care and care in the cultural community is an important means for compliance with the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander child placement principle.

Research on kinship care in Australia to date is sparse, although during this conference at least two papers will report on research and practice in NSW. Overseas research has documented positive benefits in terms of continuity, stability and well-being, particularly in relation to cultural identity - aspects highlighted in the UN Convention (George and van Oudenhoven

2002). Against this, concerns for the child in some placements centre mainly around safety issues (Ainsworth and Maluccio 1998). Overall, however, of greater significance are concerns for kinship carers who may receive little or no formal support from a state preoccupied with cost-cutting and welfare reform (Sultmann and Testro 2001). Moreover, given the strong preference for kinship care placements for Indigenous children, this may lead, in effect if not in intention, to an inequitable distribution of resources on racial grounds.

In the UK, the Family Rights Group has documented particular concerns of grandparents who experience physical and financial stress, yet may be deterred from seeking support through fear of losing their grandchildren into foster care with strangers, and on to closed adoption through the push for permanency planning ( Richards 2001).

With the increase in birth parents affected by drug use (Tomison 1996; Ainsworth and Summers

2001), the number of informal and formal grandparent carers is likely to grow, with implications for both policy and practice. Grandparents’ support groups have sprung up in three Queensland centres already this year, with aims to clarify legal rights and improve access to financial assistance and services. While on balance grandparents speak positively of their new and unexpected role, investigative research (Frazer 2002) confirms the need for information, support, recognition, and respect – that key concept introduced in the opening to this paper.

Foster Care

Turning to foster care in general, it’s impossible here to provide an exhaustive survey of evidence to date on what works in foster care practice. Moreover, a whole day will be devoted to this topic with Peter Pecora on Wednesday. There are, however, aspects of current critical

7 concern that merit mention, and in doing so I will draw particularly (but not exclusively) on recent and current Australian research studies, which focus on foster carers.

Included with the handouts is a copy of the overview of foster care research findings compiled by Barber and Gilbertson and reproduced in the Autumn 2002 issue of the ACWA Journal

Developing Practice (Barber and Gilbertson 2002). In their monograph, Foster Care: The State of the Art

, Barber and Gilbertson lament the lack of “hard evidence” from controlled outcome studies in foster care (2001 p54). Nevertheless, they proceed to outline propositions for which they consider there is at least a moderate degree of empirical support. Many of these propositions are useful for practitioners to note, and especially so, given that some may challenge aspects of current practice. In particular, I draw your attention to the issues of sibling co-placement and continuing contact with birth parents and family, both of which have been found in many studies to be preferred by most children and young people in foster care.

While such factors are not in themselves always associated with improved outcomes, as valued by researchers and professionals, neither are they associated with poorer outcomes. Moreover, as I will argue later, a case can be made for real consideration of children’s preferences to be regarded as a highly valued outcome in and of itself.

In support of this stance, UK researchers Sinclair, Wilson and Gibbs assert “there are no substitutes for listening carefully to what those involved want and weighing up the factors in each case” since there are “no rules of thumb that apply in all circumstances” (2000 p193).

Another problem with “rules of thumb”, or simplified tick-lists of research findings, is that findings may be used in inappropriate ways. Take for example, the sixth characteristic of foster carers that has been associated with successful placements: “female carers who, from personal experience, identify with deprived or damaged children” (Barber and Gibertson 2002). While this may resonate, in part, with practice wisdom, it would be risky, in this simplified form, to be included as a basis for recruitment and selection of new foster carers. The finding is from a single research study with long term foster carers who by definition were relatively successful

(Dando and Minty 1987). By contrast, a number of practice writers have drawn attention to a connection between some foster carers’ own childhood experiences of deprivation and a lack of success in fostering (Josselyn 1952; Jenkins 1965; Kay 1966). From this it would seem that identification with deprived children may or may not be a positive characteristic, and further research is needed to distinguish among potential foster carers with this motivation. In this regard, I’d like to draw your attention to a poster presentation at this Conference of current research by myself and Marie Caltabiano on foster carers’ own childhood experiences and foster caring role performance. This research is in process, but Marie and I hope to be able to report findings at the next ACWA Conference.

Turning to some recently completed Australian research studies with foster carers (McHugh

2002; AFCA 2001), the most salient findings to emerge centre around the need for greater levels of financial and other support, given the increasing demands of the fostering role in caring for children and young people with special or extraordinary needs. In a session this afternoon on the costs of foster care, Marilyn McHugh, Bev Orr and Sue Tregeagle will discuss the policy implications of a landmark national study (McHugh 2002). Without wishing to pre-empt what will be presented at that session, it is clear that, while there is no strong evidence of a clamour by foster carers for payment as salaried professionals, there is serious concern about current levels of foster care payments which do not even cover actual costs let alone afford children and young people an enhanced quality of life. As George and van Oudenhoven assert “foster care works

8 better when foster families have adequate and stable finances” (2002 p89). It also works better when other forms of support are readily forthcoming. Unfortunately, however, the recent nationwide study undertaken by the Australian Foster Care Association (AFCA 2001), identified considerable unmet need amongst foster carers for recognition, respect, support, protection and training. It also found widespread dissatisfaction on an everyday level, with many aspects of the foster care service across the board in relation to “information, resources, relationships and decision making” (a schema devised by Connie Benn (1976) with the Brotherhood of St

Laurence Family Centre project).

Beyond the day-to-day level, a serious sense of grievance was found at the lack of support in relation to stressful events, and in particular in relation to the investigation of allegations of abuse by foster carers, an event which has become more common with the increasing severity of the needs of children and young people in foster care.

These Australian findings with regard to support are consistent with those of other recent studies with foster carers in the UK (Triseliotis, Borland and Hill 2000; Sinclair, Wilson and Gibbs

2000). Together, such studies highlight the gravity of the current crisis in foster caring.

In addition to financial and other forms of support, a need for appropriate forms of education and training also has been identified, and this afternoon Anne Butcher will present some preliminary findings from her current research in the Mackay/Whitsunday region of Queensland.

Involvement of foster carers as important team members in case planning and review is also advocated, and where the Looking After Children materials are in use, this is being implemented

(Cheers 2002). Elsewhere, however, foster carers complain about a lack of respect afforded them, particularly by government workers, and this is evident in preliminary findings from my current research with colleagues in North Queensland (Thorpe, Bishop, Butcher, Daly, Lovatt and Reck 2002). It is hard to fathom precisely why this should be so beyond hypothesising it as an undesirable reflection of a child protection/child welfare system under extreme stress. Again, we hope to present more definitive findings at the next ACWA Conference. Meanwhile, if you’d like to know more about this collaborative research between James Cook University and the

Mackay/Whitsunday Region of the Queensland Department of Families, we have a poster on display at this conference.

Permanency/Stability/Continuity Planning and the place of Adoption .

Embedded in current Anglo/American research and discourses about foster care, is a concern with what is variously conceptualised as the child or young person’s need for permanency, stability or continuity. In North America, where children are described by President Bush as

“languishing in foster care” (Reuters, 2002) this has led to a focus on planning for adoption by strangers of children for whom reunification with birth family is not possible. Similarly, in the

UK the Blair government has set targets, linked to financial incentives, for an increase by up to

40% in the number of children in care who are adopted (Warman and Roberts 2001). I understand that in NSW a similar policy emphasis on adoption has emerged in recent years, despite some overseas evidence that there is a serious shortage of adoptive families for all except the very youngest children in care (Cashmore 2001).

In my own state, Queensland, attention is being focussed not so much on adoption but rather on the provision of long-term stable and secure care for children and young people; that is, on

9 arrangements that simultaneously can provide for stability and for continuity both of relationships and of cultural identity. In this regard, the Queensland approach is supported by some recent research from the UK, the USA and western Europe.

June Thoburn, for example, reports a similar breakdown rate in adoption placements of noninfants as in permanent foster care placements (Thoburn 1991), and in the study by Sinclair,

Wilson and Gibbs (2000) as many as 11% of their sample of children in foster care had entered care as a result of adoptive home breakdowns. Confirming the vulnerability of adoptive placements for non-infants, Nigel Lowe and colleagues (2000) found that many children adopted from care have complex health and educational needs which require additional, specialist help which often was not readily available in post adoption support services.

By contrast, comprehensive post-adoption support services are available in the Netherlands

(Juffer 2001), and also in some parts of the USA, where such services facilitate open adoption arrangements with continuing birth family contact. In this regard, Ruth McRoy’s research identified better outcomes in terms of both stability and continuity of relationships and cultural identity in open adoptions, and especially in adoptions by foster carers rather than strangers.

Moreover, Afro-American children in particular benefited from kinship open adoptions (McRoy

2001).

Quite detailed evidence of what works in managing contact arrangements in open adoption is provided in a newly published book by Hedi Argent (2002). In this book, adopted children and young people and their families give their opinions and share their experiences. As the back cover claims, “not everything works for them but a great deal does and they illuminate all that can be said about managing contact arrangements” (Argent 2000). Clearly, detailed reflections on practice help to flesh out the findings of research in ways that are of immense value for practitioners.

Staying connected is certainly an emerging focus of interest in attempts to provide stability or permanence for children in long-term care. Adoption is only one way and, indeed, can have disadvantages in terms of limited, ongoing support compared with long term foster care.

Additionally, in New Zealand as well as many European countries, adoption is rarely considered as an option for children in care and especially not if it is against the wishes of birth parents or of children and young people themselves (Iwanek 2001).

In countries such as Sweden (Andersson 2001), Denmark (Nielson 2001), and France (Dumaret and Rosset 2001) long-term foster care is seen as a positive form of care which can provide psychological security together with ongoing relationships with birth family, co-placement with siblings, support with health and disability issues and, in Denmark, ongoing support up to age 22 years. In these European countries, it is recognised that many children in care end up advantaged, with two families for life or what George and van Oudenhoven describe as a

“composite family” characterized by connectedness, permeable boundaries and complementary care (2002 p23).

In many European countries, then, continuity is regarded as a more important goal and outcome than permanence through adoption (Warman and Roberts 2001). And in the UK, in a recent report of a study comparing adoption with long term fostering, Nigel Lowe and Mervyn Murch conclude by emphasising “the positive role that long term fostering can play” (2002 p156) for children and young people for whom reunification is not a possibility.

10

Clearly, there is evidence to be found of what works in long-term care beyond the adoptionfocussed permanency planning research and practice literature. Such alternative evidence is important in helping us devise local Australian solutions that are contextually appropriate, given our heightened awareness of the impact of enforced separation from birth families on Indigenous

Australians (HREOC 1997) and, indeed, on non-Indigenous people through the experience of child migrants from Britain (Gill 1997), adopted persons’ search for their origins (Swain and

Swain 1992) and the searches for family by members of Care Leavers in Australia Network (The

CLAN Newsletter, available from PO Box 164, Georges Hall 2198).

As Fran Crawford has argued, “as practitioners we are part of making knowledge for particular purposes and particular sites and particular plays of power. We are not just applying knowledge that is developed elsewhere” (2002 p4).

Participation of Children and Young People

Increasingly, human service researchers and practitioners around the world are recognising the importance of making decisions with people rather than for them. This is consistent with the

International Human Development Framework advocated by George and van Oudenhoven in relation to foster care (2002). In this regard, recognition of the right of children and young people in care to participate in decision-making about their lives has come relatively recently, spurred by the findings of research with young people both in care and leaving care (see for example in Australia, Cashmore and Paxman 1996; Owen 1996; Community Services

Commission 2000). In addition, the formation in Australia in 1993 of what is now called the

CREATE Foundation has provided added impetus for the voices of children and young people to be respected, listened to and taken seriously.

Concerned about the poor quality of their lives in care, and severely limited life outcomes on leaving care, the purpose of the CREATE Foundation is to enhance the Human Rights and empowerment of each young person in care, and to achieve on-going changes to State care systems for the benefit of young people taken into care in the future. Of particular concern is the experience of multiple placements in care, combined with disconnection from direct family and extended family networks. Disillusioned with the ability of systems and professionals to protect and enhance their well being, young people are asking for choices and the opportunity as early as possible in their lives to participate actively in all decisions which affect their lives

(www.create.org.au).

Research with young people in foster care suggests that many seek both stability and ongoing relationships with birth parents and siblings (George and van Oudenhoven 2002 p97). However, not all young people will have identical preferences, which is why Sinclair, Wilson and Gibbs

(2000) emphasise listening to children and respecting their wishes. This is critically important when young people’s preferences differ markedly from the views of professionals. In this regard, Lowe and Murch note that in two cases in their study “adoption remained the plan despite the child’s wishes to the contrary” (2002 p83).

In a similar vein, George and van Oudenhoven cite research with street children which revealed

“a different set of priorities to those assumed by the adult professionals wanting to help them”

(2002 p44).

11

Whereas professionals were concerned to focus on lack of shelter, malnutrition and loneliness, young people wanted assistance in ending police harassment and obtaining better work. George and van Oudenhoven summarise from around the world the experiences and views of children and young people who fend for themselves:

not necessarily homeless

may live in quasi/pseudo family settings: some altruistic; some exploitative/abusive

may be taken under the wing of older street kids

often have networks of contacts/occasional support: “loose fostering”

value quasi adult privileges

sense of having control of their lives

peer loyalty is very important

often have a sense of community

want help re: ending police harassment; securing better work

Despite the positives identified by street kids, we know that their adult life outcomes are significantly poorer than for young people in other forms of out-of-home care. We also know that attempts to fit street kids into conventional care options are often doomed. Rather than abandoning them long before they formally leave care, it could be worthwhile to listen to what street kids themselves say and experiment with unconventional and “loose fostering” arrangements that fit better with their preferences (George and van Oudenhoven 2002). Clearly, what we need are more detailed practice accounts of what works well with young people who fend for themselves.

Similarly, we need to hear about research and practice that succeeds in involving the participation of children and young people in care. In this regard, I draw your attention to a poster at this Conference by Wayne Daly highlighting his work with CREATE in Mackay, North

Queensland.

Participation of “birth” families.

Pursuing further the theme of stakeholder participation, my final focus is on the “birth” families of children and young people in care. Hitherto, frequently “written off” by professionals, “it is now realised that parents and grandparents can offer a great deal and that it serves all parties best to draw them in as much as possible” (George and van Oudenhoven 2002 p71). While this realisation may already apply in the context of using the Looking After Children materials

(Cheers 2002), and where foster care is seen as a child protection service with the goal of reunification (Sultmann and Testro 2001), there is continuing evidence of birth families feeling sidelined and disempowered in relation to their children in long term care (Thorpe 1993;

Fernandez 1996; Community Services Commission 1999); and this is so despite the expressed preference of children for continuing contact. Such professional neglect is evidenced by the sparsity in Australia of literature about practice with parents of children in care, and the lack of significant current research.

An immediately apparent and notable exception to this claim is the session scheduled for this afternoon with Theresa Burgheim, addressing implications for practice of the grief of families whose children have been removed.

12

In addition, as part of our current research program in North Queensland, Wayne Daly is planning a small research study to explore with birth parents their views on “ what makes a good foster carer?”

Much more, however, needs to be done. June Thoburn, for example, in the UK has identified a pressing need for research on the outcomes for birth parents of permanent placements (Thoburn

2001).

And in Australia, Frank Ainsworth (2001) has called for research on drug using parents and family reunification practice undertaken, as Tomison (1996) suggests, in collaboration with drug and alcohol agencies. Certainly, the issue of increasing numbers of drug using parents is a serious and growing contemporary challenge for child protection services. Equally serious, are the challenges posed by Aboriginal families and communities described by Boni Robertson as dysfunctional in the sense of being “unable to function because of pain and social disarray”

(Robertson 1999 pxxii). In papers to be given this afternoon, real partnership with Aboriginal families and community development approaches will be presented as examples of practices that work.

Despite the difficulties in facilitating the participation of birth parents in out-of-home care, we know that it is important to children and young people regardless of whether reunification will be possible. Perhaps what practitioners need are detailed accounts of practice that works, for example in relation to the involvement of parents seen as “difficult” in the Looking After

Children systems. From my own experience over many years of working with birth parents in support and advocacy groups, their major concerns centre around rather basic elements of good interpersonal communication. Parents value workers who show respect for them as a person, while not condoning what they may have done in relation to their child. Such respect parents see as manifest through a worker’s

willingness to help,

seeing a parent’s point of view

open mindedness

being humane

Conversely, a lack of respect is sensed when workers

fail to apologise for “stuff ups”

fail to follow through on proposals made in case planning meetings

fail to value a parent’s wishes in regard to their child’s care

fail to appreciate parents’ strengths and positive qualities

expect parents to be submissive

misunderstand assertiveness as aggression

reduce contact as a form of punishment, or for no apparent reason

misinterpret grief reactions as lack of interest

(The parents with children in care group, Townsville 1990).

In my experience, by and large, parents respond positively to workers who treat them with respect and see something to like in them. In such circumstances, parents can accept the reality of their child being in care, can participate well in case planning, and are particularly concerned about their children’s educational development.

13

In working with parents, what has always impressed me is the far reaching difference that respect can make. And as we have seen, this basic but powerful concept is central to practice that works well with all participants in out-of-home care.

Conclusion

In concluding this paper I would like to return to the critical questions posed at the start concerning appropriate knowledge and its use in practice.

When I first studied social work over 30 years ago one keenly debated issue revolved around whether social work is art or science. The prevailing view then was that an integration of the humanistic art of practice with the science of knowledge was the hallmark of our distinctive profession. Since then, the pursuit of professional respectability has led to an implicit de-valuing of the art of practice in favour of the embrace of science, as in the call to adopt evidence-based decision making. What this means is spelled out in the current issue of Developing Practice

(2002 p39), with an extract from the website of the UK Centre for Evidence Based Social

Services.

While I have no quarrel with the call for research evidence about what works to inform our practice (I am after all a researcher), I do question the presumption that research is value-free and thus inherently superior to professional judgment shaped by practice wisdom about what works.

It seems to me that we should draw on a range of different sources of knowledge, including research that is appropriate and applicable in our particular local contexts. We should also be critically alert to the influence of values and ideology on both how research is framed and on what we count as practice wisdom. Disregard of values cannot be sustained once we acknowledge the legitimacy of different stakeholder views about desirable outcomes and means for achieving them.

At the outset of this paper I outlined an International Human Development Framework which shaped my choice of arguments on what we know about outcomes in practice. I recognise that some of you may question the framework that I chose to use and the evidence that I drew on to support the use of that framework. In my view this serves to highlight the reality that evidence based practice is no simple panacea. A high degree of professional skill, in the art of practice, continues to be essential in assessing the complexity of factors in individual situations, in listening carefully to the views of those involved, and in making informed decisions about children and young people’s lives – preferably with them rather than for them. However, this latter point, of course, is a preference shaped by my preferred frame of reference.

This brings us inescapably back to consideration of the interplay of values and knowledge. And on this note I will finish and invite stakeholder responses and discussion.

14

REFERENCES

AFCA (2001) Supporting Strong Parenting in the Australian Foster Care Sector Canberra:

Australian Foster Care Association

Ainsworth, F. and Maluccio, A. (1998) Kinship Care: false dawn or new hope? Australian Social

Work 51(4) 3-8.

Ainsworth, F., and Summers, A., (2001) Family Reunification and Drug Use by Parents

Perth:Western Australia. Department of Family and Children’s Services.

Andersson, G. (2001) Achieving Permanency in long term foster care. Unpublished paper presented at Adoption Now: A Solution for Looked After Children? International Seminar

London July 5.

Argent, H. (2002) Staying connected: Managing Contact in Adoption. London:BAAF.

Bath, H. (1997) Recent Trends in Out-of-Home Care of children in Australia. Children Australia

22, 4-8.

Bath, H., (1998) Trends and Issues in the Out-of-Home Care of children in Australia,

International Journal of Child & Family Welfare (2) 103-114.

Barber, J.G. and Gilbertson, R. (2001) Foster Care: The State of the Art

Adelaide:Australian Centre for Community Services Research.

Barber, J.G. and Gilbertson, R. (2002) Foster Care Practice: What Does the Research Say?

Developing Practice Number 3, 34-35.

Benn, C. (1976) A New Developmental Model for Social Work in P.J. Boas and J. Crawley (eds)

Social Work in Australia: Responses to a changing context Melbourne: Australian

International Press.

Cashmore, J. (2001) What we can learn from the US experience on permanency planning?

Australian Journal of Family Law No 15 pp 215-229.

Cashmore J. and Paxman M (1996) Wards Leaving Care: A longitudinal Study. Sydney: NSW

Department of Community Services

Cheers, D. (2002) Looking After Children (and their parents!) in Australia Developing Practice

Number 4, 54-59.

Community Services Commission (1999) Keeping Connected: Contact Between Children in

Care and their Families Surry Hills, Sydney

15

Community Services Commission (2000) Voices of Children and Young People in Foster Care:

Report from a consultation with children and young people in foster care in NSW. Surry

Hills, Sydney.

Crawford, F. (2002) Some “Foucauldian tips for Social Work Practice Praxis

Perth: Curtin University School of Social Work, pp 4-5

Dando, I. And Minty, B. (1987) What makes good foster parents?

British Journal of Social Work 17 383-400.

Delfabbro, P., Barber, J., and Cooper, L. (2000) Placement disruption and dislocation in South

Australian Substitute Care Children Australia 25, 16-20.

Dodson, M. (1999) Indigenous Children in Care: On Bringing Them Home Children Australia

24 (4).

Dumaret, A. and Rosset, D. (2001) Simple Adoption, Fostering and the Placement of Children in

Long Term Care Unpublished paper presented at Adoption Now: A Solution for Looked

After Children? International Seminar London July 5.

Fernandez, E., (1996) Significant Harm:Unravelling Child Protection Decisions and Substitute

Care Careers of Children. Aldershot: Avebury, Ashgate.

Frazer, I., (2002) A Home Away from Home Townsville Bulletin Saturday, May 11, pp. 48-49.

George, S., and van Oudenhoven, N. (2002) Stakeholders in Foster Care: An International

Comparative Study. Louvain-Apeldoorn: IFCO and Garant.

Gill, A. (1995) Orphans of the Empire. Sydney, Millenium Books.

HREOC (1997) Bringing Them Home Report of the National Inquiry into the separation of

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Children from their Families. Sydney: Human

Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

Iwanek, M. (2001) Using Family Placements Unpublished paper presented at Adoption Now: A

Solution for Looked After Children? International Seminar London July 5.

Jenkins, R. (1965) The Needs of Foster Parents Case Conference 11 (7) 211-19.

Josselyn, I.M. (1952) Evaluating the motives of Foster Parents, Child Welfare 31 (2).

Juffer, F. (2001) Supporting new Adoptive Placements Unpublished paper presented at Adoption

Now: A Solution for Looked After Children? International Seminar London July 5.

Kay, N. (1966) A Systematic Approach to Selecting Foster Parents. Case Conference 13(2).

Lowe, N. and Murch, M. (2002) The Plan for the Child: Adoption or Long Term Fostering?

London:BAAF.

16

Lowe, N., Murch, M. Borkowski, M., Weaver, A, Beckford, V. and Thomas, N. (2000)

Supporting Adoption. Reframing the Approach. London:BAAF.

Lynn, R., Thorpe, R., Miles, D., Cutts, C., Butcher, A. and Ford, L. (1998) Murri Way!

Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders Reconstruct Social Welfare Practice. Townsville:

James Cook University, Centre for Social and Welfare Research.

McHugh, M. (2002) The Costs of Caring: A Study of Appropriate Foster Care Payments for

Stable and Adequate Out of Home Care in Australia. Sydney: Social Policy Research

Centre, University of NSW.

McRoy, R., (2001) Birth Families, Contact and Issues of Identity. Unpublished paper presented at Adoption Now: A Solution for Looked After Children? International Seminar London

July 5.

Maluccio, A., Ainsworth, F., and Thorburn, J. (2000) Child Welfare Outcome Research in the

United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Washington: CWLA.

Neill, R. (2002) White Out: How Politics is Killing Black Australia. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

Nielson, H. (2001) Using Residential placements for children and young People. Unpublished paper presented at Adoption Now: A Solution for Looked After Children? International

Seminar London July 5.

Owen, J. (1996) Every Childhood lasts a lifetime. Brisbane: Australian Association of Young

People in Care.

Portengen, R. (2001) Netwerkpleezorg Utrecht: Nederlands Institut voor Zorg en Welzyn.

QDOF (2002) Families News No. 27, June 26.

Reuters (2002) Die-hard Republican heads campaign for kids The Australian Thursday July 25 p. 8.

Richards, A. (2001) Second Time Around. A Survey of Grandparents Raising Their

Grandchildren. London: Family Rights Group.

Robertson, B. (1999) Aboriginal and Torres Strait islander Women’s Task Force on Violence

Report. The State of Queensland.

SNAICC (2002) Their Future: Our Responsibility. Northcote, Victoria: Secretariat of National

Aboriginal and Islander Child Care.

Sinclair, I. Wilson, K. and Gibbs, I. (2000) Supporting Foster Placements: Report Two York:

Social Work Research and Development Unit, The University of York.

Sultmann, C. and Testro, P. (2001) Directions in Out of Home Care: Challenges and

Opportunities Brisbane: Peak Care Queensland Inc.

17

Swain, P. and Swain, S. (1992) To Search For Self: The Experience of Access to Adoption

Information. Sydney: The Federation Press

The Parents With Children in Care Group, Townsville (1990) Issues for Discussion with the

Department of Family Services. Unpublished paper.

Thoburn, J. (1991) Evaluating Placements: Survey Findings and Conclusions, in J. Fratter,

J. Rowe and J. Thoburn (Eds) Permanent Family Placement: A Decade of Experience.

London:BAAF.

Thoburn, J. (2001) Adoption: Planning for Permanency paper presented at the Adoption Now: A

Solution for Looked After Children? International Seminar, London July.

Thorpe, R. (1993) Empowerment Groupwork with Parents of Children in Care in J. Mason (ed)

Child Welfare Policy: Critical Australian Perspectives. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger.

Thorpe, R. (2002) Children in Care:Some Current Australia Perspectives. Developing Practice number 3 pp. 12-17.

Thorpe, R., Bishop, M., Butcher, A.,Daly, W., Lovatt, H. and Reck, C. (2002) Foster Care

Research in Queensland and Contemporary Foster Care Issues. Key note presentation

“Informing Practice” Conference of the Queensland Association of Fostering Services.

Mackay July.

Tomison, A.M. (1996) Child Maltreatment and Substance Abuse Discussion Paper 2 National

Child Protection Clearing House, Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

Triseliotis, J,. Borland, M. and Hill, M., (2000) Delivering Foster Care. London:BAAF.

United Kingdom Centre for Evidence Based practice (2002) What is Evidence Based Practice?

Developing Practice No.4 p39.

United Nations (1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Warman, A. and Roberts, C. (2001) Adoption and Looked After Children. International

Comparisons. Family Policy Briefing 1 Oxford: Department of Social Policy and Social

Work, University of Oxford.

Whittaker, J. (2000) The future of Residential Group Care Child Welfare. 79(1) 59-74.

Wise, S. (1999) Children’s Coping and Thriving Not Just in Care Children Australia 24(4) 18-

28.