The Fire Next Time

advertisement

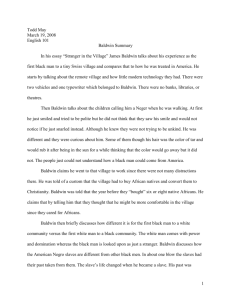

The Fire Next Time James Baldwin (1963) Magdalena J. Zaborowska, University of Michigan Domain: Literature. Genre: Essay Collection. Country: USA, North America. In 1963, Baldwin’s words electrified the world as The Fire Next Time ricocheted across the Atlantic and beyond, following the publication of two essays that comprise it in The Progressive and The New Yorker the year before: “My Dungeon Shook: Letter to My Nephew on the One Hundredth Anniversary of the Emancipation” and “Down at the Cross: Letter from a Region in My Mind”. While the huge sales of this book and its presence on bestseller lists solidified Baldwin’s stature as one of the most prominent writers and intellectuals in the United States, its praises and critiques re-cast his reputation in deepened racialized tones. As F.W. Dupee proclaimed in the New York Review of Books, “As a writer of polemical essays on the Negro question James Baldwin has no equals. He probably has, in fact, no real competitors. The literary role he has taken on so deliberately and played with so agile an intelligence is one that no white writer could possibly imitate and that few Negroes, I imagine, would wish to embrace as a whole.” In The Fire Next Time Baldwin is at the height of his artistic powers and this work has been revered for its masterful style and composition, prophetic tone, and parabolic, dramatic casting of the history of American race relations through a complex white-black dialectic extending from Baldwin’s autobiographic insights to commentary on national and global political and economic situation. While arguing that the details of the system of oppression experienced by American blacks reflect a larger design of western culture as a prison filled with signifiers of various systems of oppression: “totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, [and] nations”, Baldwin also shows that the American state’s refusal to take responsibility for the historic and political conditions that resulted in the creation of the Soviet Bloc and the Cold War has to do with the compulsion of racialist thinking at home: “Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not want to face, and what white Americans do not want to face when they regard a Negro: that life is tragic”. While developing this somewhat existentialist stance, one that might echo his fascination with Dostoyevsky, Baldwin stresses the American imperial project as a collective enterprise of perpetual self-delusion and calls on black American artists and non-racist whites to stand up to the task of remaking the world beyond dichotomies and delusions. This epistolary account in The Fire begins with “My Dungeon Shook”, the testament-manifesto addressed to his fourteen-year-old nephew and namesake, James, who stands for the younger generation of blacks struggling for civil rights. This shorter letter-essay addresses the wider place of race in national history and psyche and identifies blackness as positioned squarely in the center of Americanness as its “immovable pillar”. Baldwin then transitions into the next letter-essay, “Down at the Cross”, which opens with a reference to himself at fourteen, during a “prolonged religious crisis”, which brings issues of social justice and spirituality together. Baldwin’s autobiographical narrator recounts his childhood in Harlem and his quest for a “gimmick” that would save him from the sinister forces of the “Avenue” – “the whores and pimps and racketeers”. When one day a pastor, an “extremely proud and handsome woman, with Africa, Europe, and the American of the American Indian blended in her face”, asks him, “Whose little boy are you?” Baldwin admits to having “surrendered to a spiritual seduction long before I came to any carnal knowledge”, by immediately answering “Why, yours.” Young Baldwin yields to the church because there is not much choice to be had, and he cannot think of another gimmick to escape the pull of the Avenue: “one doesn’t, in Harlem, long remain standing on any auction block. It was my good luck – perhaps – that I found myself in the church racket instead of some other.” The church gives Baldwin’s narrator only a temporary refuge and religion offers no lasting protection from the need to know and learn more than the doctrine allowed. When novels enter his imagination, he has to betray the Book, having been seduced by a multitude of texts: “I date it – the slow crumbling of my faith, the pulverization of my fortress – from the time, about a year after I had begun to preach, when I began to read again. … I began, fatally, with Dostoevski … in a high school that was predominantly Jewish. … I realized that the Bible had been written by white men”. As he opts for a literary rather than religious mountaintop, the walls of Baldwin’s faith crumble not only under the influence of impressive Jews and Russians, but also due to a discovery that had nothing to do with the ethnicity or phenotype of the actual writers of the bible, but everything to do with Baldwin’s revelation that American religious institutions depended on the same racist hierarchies that he had experienced everywhere else in his country. Baldwin’s intense reading period in high school is a quest in itself, one dominated by issues of race and authorship as he traces his struggle to accept his calling as a writer/prophet. Along the axis of Baldwin’s uptown-downtown shuttling between the two incompatible worlds of Harlem and his church, and Clinton De Witt High School in the Bronx, his self-preoccupation as an artist in the spiritual, moral, even metaphysical sense emerges as somewhat romantic. Even more significantly, the actual geographic distance and mental leap required to negotiate these two worlds meant a “terrible mental struggle”, as Leeming emphasizes. “The trip each day to Clinton was long in terms of time and miles. In terms of landscape, attitudes, and possibilities, the distance was enormous.” At the same time, Baldwin’s “romantic” departure from the church entails a rational rejection of Christianity and institutionalized religion, a social protest against the binary notions of race and gender, and an artistic commitment of his poetics to the politics and materiality of everyday experience in a racialized society. By the time he embraced some of the ideological tenets of the social struggle that many of his high school friends toted, religion had become to him, as Leeming stresses, a “sexless, bookless future, ruled by the saints in their white robes and the all-toolikely white god in his.” The Fire also recounts Baldwin’s meeting with Elijah Muhammad of the Nation of Islam at Muhammad’s Chicago South Side house. Following a heated discussion, in which Baldwin makes clear, once more, that “it was impossible to indoctrinate me”, Baldwin’s narrator hesitates about giving the Muslim driver the address – “the kind of address that in Chicago, as in all American cities, identified itself as a white address by virtue of its location”. While waiting for the car, Baldwin and Muhammad stand in front of the house, “facing these vivid, violent, so problematic streets”. This contemplation of the South Side – “a million in captivity” – makes Baldwin regret his ideological disagreement with Muhammad: “I felt very close to him, and really wished to be able to love and honor him as a witness, an ally, and a father. I felt that I knew something of his pain and his fury, and, yes, even his beauty. Yet precisely because of the reality and the nature of those streets – because of what he conceived as his responsibility and what I took to be mine – we would always be strangers, and possibly, one day, enemies.” As someone straddling boundaries and fighting to eradicate racial fault lines – “The unprecedented price demanded – and at this embattled hour of the world’s history – is the transcendence of the realities of color, of nations, and of altars” – Baldwin proclaims that he would never “make [his] … peace with the ghetto” and “die and go to Hell before … [he] would accept … [his] ‘place’ in this republic”. The segregated, wounded and divided neighborhood, city, and nation provide a blueprint for Baldwin’s plan of national integration through a philosophy of humanism based on self-knowledge and a revolutionary understanding of “love”. Baldwin ends “Down at the Cross” with the much-quoted jeremiad: “If we – and now I mean the relatively conscious whites and the relatively conscious blacks, who must, like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others – do not falter in our duty now, we may be able ... to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world.” The book’s final warning and prophecy of violence were fulfilled when the nation’s cities erupted in riots and racial unrest through the 1960s. More than forty years after the publication of the two essay-letters comprising The Fire Next Time, Baldwin’s work is still mostly remembered in association with the social upheaval upon which he so fervently commented. Much has been said about this writer’s passionate plea for racial equality and his ability to see the world through the plight of African Americans. Not enough attention has been paid, however, to the ways in which he uses this plight as a lens through which to study the structures and forms of white supremacy and its reliance on the black presence and otherness at the core of its vision of the American nation. At the height of his fame, following the publication of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin became a national icon of blacknes and spokesperson for racial justice, at the same time as he was fast becoming a somewhat ambivalent symbol of American unease about integration and sexuality. Baldwin’s earlier and subsequent works made it clear that to him freedom of bodies of different “colors” to be in proximity included the freedom for different “sexual orientations” within the nation – a point only implicit in the text of The Fire but one that Baldwin would come back to explicitly and repeatedly throughout the rest of his career, even though it caused many negative reactions to his works and person. Published 08 April 2004 Citation: Magdalena J. Zaborowska, University of Michigan. "The Fire Next Time." The Literary Encyclopedia. 8 Apr. 2004. The Literary Dictionary Company. 8 January 2007. <http://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=857> This article is copyright to ©The Literary Encyclopedia. For information on making internet links to this page and electronic or print reproduction, please read Linking and Reproducing.