The Weary Blues - Humble Independent School District

advertisement

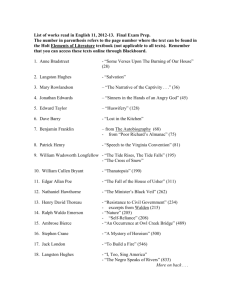

“The Weary Blues” “The Weary Blues” – Langston Hughes (Poet’s Life) The publication of “The Weary Blues” in 1925 was the centerpiece of one of the most successful publicity stunts in literary history, one that elevated its author, Langston Hughes, to fame as a leading African American writer. Hughes thought of himself as a poet, but like most modern poets, found that he had to write in other formats to support himself, and so he was also a short-story writer, novelist, essayist, and newspaper columnist. Hughes is generally ranked among the greatest African American writers of the first half of the twentieth century; he is slightly older than the novelists Ralph Ellison and Richard Wright, who are the best comparisons for his literary achievement. Hughes is a figure of the Harlem Renaissance, the flourishing of black artistic achievement centered in the Harlem neighborhood of New York City during the 1920s. Hughes was widely traveled, and his aesthetic and political views were informed by the wider perspective of an international black community embracing Paris, Africa, and the Caribbean. “The Weary Blues” was written at the beginning of Hughes's career. It brought him popularity in the black community as a leading poet and representative voice, as well as in the American scene at large, popularity that had him using his summer breaks from college for national book tours. AUTHOR BIOGRAPHY James Langston Hughes usually stated that he was born on February 1, 1902, in Joplin, Missouri, but with no birth certificate, he was not completely certain. This uncertainty can stand, perhaps, as a symbol of the marginal nature of the world he was born into, a world in which African Americans were treated as something less than full citizens because of the segregation and discrimination written into the legal codes and accepted in society. Hughes's mother, Carrie, came from an upper level of the African American community. (Her uncle, for instance, was a congressman during Reconstruction, an American diplomat, and eventually the president of Virginia State University.) She ran away from home, though, dreaming of a career on Broadway. This career did not materialize, and she eventually married James Hughes, who worked as a Pullman porter (an attendant on the sleeping coaches of trains), a prestigious job in the black community. Carrie eventually worked as a schoolteacher, so the family should have had a comfortable middle-class life. However, Hughes's father could not stand the daily wounds to his pride that life in the United States meant for a black man, so he moved to Mexico City. His wife did not follow, and by the time Langston was six years old, his parents were separated. Growing up in Kansas and Ohio, Hughes did not face the extreme discrimination experienced by blacks living in the South, but he felt all the more keenly the unfair treatment he did experience. (He particularly felt the sting when his white schoolmates praised him for his rhythm, a stereotype about blacks.) In 1920, as soon as he graduated from high school, Hughes went to visit his father. Crossing the Mississippi River by train at St. Louis, Missouri, Hughes wrote “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” which is often regarded as his best poem. In the next year, he began publishing poetry regularly, but only in publications such as the Crisis, aimed at a black readership. Wealthy black patrons recognized his talent and paid his way to attend Columbia University for a year, but Hughes was too restless for college. He decided to see the world as a sailor, but by some misunderstanding, he spent several months on a crew tending mothballed transport ships halfway up the Hudson River. It was while he was working in 1923 or 1924 that he wrote the first draft of “The Weary Blues.” After a more rewarding period of service that took him to Africa and Europe, Hughes moved to Washington, DC, to live with his mother; there, he worked as a busboy at a hotel restaurant. He happened to see that Vachel Lindsay, one of the most prominent white poets of the era, was staying at the hotel, and quietly slipped him three of his poems, including “The Weary Blues.” The next day, Hughes read of himself in the newspaper as a great black poet found working as a busboy. This was hardly a “discovery,” since Hughes was already a wellpublished poet, but is a measure of the distance that separated the white and black worlds. The poem was published in 1925 in Opportunity. With Lindsay's help, Hughes began to publish in mainstream publications such as Vanity Fair. He almost immediately got a book contract, which resulted in his first poetry collection, published as The Weary Blues in 1926. When more patrons in the black community paid for Hughes to complete college at the all-black Lincoln University, he found himself in the unique position of having to spend his undergraduate summers on book tours. Hughes continued to be a successful writer for the rest of his life, producing new poems, short stories, plays, opera libretti, children's literature, and essays. The larger part of his audience was white readers. He also taught at the university level occasionally. He was a leader of the Harlem Renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s and lived the rest of his adult life in Harlem. He died on May 22, 1967, of complications following surgery. Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition): "The Weary Blues." Poetry for Students. Ed. Sara Constantakis. Vol. 38. Detroit: Gale, 2011. 275-298. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 6 Feb. 2014. “The Weary Blues” – Langston Hughes (Historical Events) HISTORICAL CONTEXT Harlem Renaissance Whether Hughes was principally inspired by music he heard in Harlem or elsewhere, he chose to place this poem on Lenox Avenue in Harlem. The Harlem Renaissance was a rebirth of black cultural expression through a diverse community of artists who lived in the New York neighborhood of Harlem in the 1920s. At the time it was called the “New Negro” movement, and Hughes became its leading voice. The cultural brilliance of the Harlem Renaissance blazed up from the prosperity of the 1920s and died out with the Great Depression of the 1930s. An entirely new black literature came out of the Harlem experience from a new generation of black authors, including Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, and Countee Cullen, to name only the most notable. They kept to traditional forms of Western literature, such as novels, dramas, and formally structured poetry. The key to their success was gaining the acceptance of white publishers and a reading audience that was primarily white, but to whom they could speak in their black voices. Their economic viability depended upon their white audience. The black artists of the Harlem Renaissance have been called to task for using Western forms and embracing Western tradition rather than creating a new art that took a stand against Western culture and its racism. Such an innovation, however, could not have succeeded against Western influence; the authors would have failed to make sales and find readers. The possibility of escape from Western tradition—what has been called Orientalism—is itself an inherently Western fantasy. The artists and writers who made the Harlem Renaissance were Americans, working in the Western tradition, and if they had chosen to take over and use African cultural elements, they would not have been able to do so with much authenticity. Black popular entertainers had performed for white audiences throughout much of the nineteenth century in the form of the minstrel show, which included black and white performers (both dressed and made-up as racist caricatures of blacks). In the early twentieth century, black forms of music such as jazz and the blues became popular with white audiences when nightclubs and dance halls came into existence. Eventually, it became possible for black performers to perform for white audiences in these venues. Hughes's own mother tried and failed to become such a performer. Many black performers achieved the highest level of fame and commercial success, including orchestra leaders such as Duke Ellington, soloists such as Louis Armstrong, and dancers such as Josephine Baker. Although the performances of these black celebrities entailed nothing that was not firmly grounded in Western tradition, they were lauded by white critics and audiences as authentic in part because of the primitive, even animalistic character of their art. It was no coincidence that black art rose to prominence especially after the trauma of World War I, which sent Western civilization scrambling for relief in anything that seemed non-Western or even anti-Western. Black performance became, as termed in Edward Said's Orientalism, a fantasy of everything that was non-Western, made safe for consumption by a Western audience. Harlem nightclubs became the meeting point between white and black, because blacks were not generally allowed to perform outside Harlem. The audiences at establishments such as the Cotton Club were all white. The dancer Josephine Baker left the United States after she tried to buy a drink at the bar of the same club where she was a headline performer but was refused entry by the bouncers. However, black intellectuals such as Hughes were let into the Cotton Club because white audiences found them both safe and interesting. The Harlem Renaissance made many black intellectuals and performers famous in American culture, but at the cost of being reduced to an exotic Other. Some, such as Baker and Hurston, embraced that identity. One of the dichotomies that Hughes is getting at in “The Weary Blues” is the white enthusiasm for the Harlem Renaissance and black performers despite the continuing white rejection of blacks as a people. Hughes had a special attachment to Harlem, no doubt owing to his own experience in what had been achieved there in the 1920s. Other black intellectuals and celebrities, such as Richard Wright (a novelist who vies with Hughes as the greatest writer of the Harlem Renaissance) and Baker, moved to France as soon as they practically could to be free of the racism inherent in the American culture of that time. (Baker, ironically, had to live under the Nazi occupation.) But Hughes stayed in Harlem until his death in 1967, long enough to see its decline into one of the poorest, most crimeridden neighborhoods in America. Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition): "The Weary Blues." Poetry for Students. Ed. Sara Constantakis. Vol. 38. Detroit: Gale, 2011. 275-298. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 6 Feb. 2014. “The Weary Blues” – Langston Hughes (Criticism) POEM SUMMARY Lines 1–18 “The Weary Blues” consists of a narrative spoken by an anonymous narrator in which are embedded two fragments of a song performed by a bluesman that the speaker hears (lines 19–22 and 25–30). The poem begins with a recollection of hearing the bluesman sing and play. In the first sentence, the performer is identified as African American using the term Negro, a term now outdated but still current when this poem was written. The word is capitalized, lending it a special dignity. The music is described with technical terms that would signal, especially to a white audience, that he is performing traditional black music. Since ragtime had become popular a generation before, syncopation (irregular musical rhythm) was associated with black music. Hughes evokes terms characteristic of black performance that would later pass into popular white culture. Crooning, originally a term referring to birds' song, was applied to black singing as a metaphor for a particular style long before it was taken up by white performers such as Bing Crosby. Similarly, Hughes anticipates the coining of the phrase “rock and roll.” Hughes uses poetic techniques such as alliteration and assonance (the repetition of sounds) to suggest the musicality he evokes with the poem. The events of the poem take place on Lenox Avenue, doubtless at one of the many jazz clubs that thrived there during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s. The structure of the poem now begins to suggest the structure of the blues, with the repetition of whole lines. Although the individual lines of the poems all stay within traditional metrical forms, the poem was considered innovative for its time for techniques such as this repetition, as well as the apparently arbitrary lengths of the lines. Although the performer is seated at a piano bench as he plays and sings, he is moving in a way that suggests dancing, and that kind of motion, as much as any musical form, is suggested by Hughes's metrical choices. The narrator contrasts the bluesman's black skin with the white keys of the piano. The piano, of course, has black keys too, so this suggests a more fundamental identification between musician and music. The melancholy feeling that will soon pour forth in the bluesman's song is already to be heard in his piano playing. The eleventh line of the poem is an interjection that breaks out of the voice of the poem thus far, invoking the spirit of the blues itself. It suggests the call-and-response format used in many black churches and among southern field laborers. It is an invocation to the power of those black traditions, and at the same time a cry of despair before the sadness of life. The blues itself is a music of sadness and loss. Lines 12 and 13 are often taken as comic, but they may also be read as serious. Although the bluesman is sitting in a precarious position, he is playing music that is ragged in the sense of being syncopated, like ragtime. Moreover, he is portrayed as a virtuoso. An idiom holds that an outstanding track-and-field athlete would be “a running fool,” that is, devoted to running beyond all reason, and the same term is applied to the bluesman's musicianship here. Lines 16 and 17 are further interjections about the blues. Experience of the blues, they suggest, however painful it may be, is not without rewards, because it is living, and not to experience them would be not living. The source of the blues, the narrator insists, is the interior mental and spiritual condition of American blacks, who have lived under one form of oppression or another for centuries. Hughes now introduces the first quotation of the blues song, describing the bluesman and his voice. He is again identified as a Negro, and the words that apply to him might just as well apply to all African Americans, weighed down with long suffering and a vast depth of sadness. The performer and his music are again strongly identified, suggesting an identity between the black experience and the blues. Lines 19–22 The poem now switches to the first snippet of the bluesman's song. He expresses the idea that he is completely isolated. He is determined not to let his loneliness get him down, but to get the better of his difficult circumstances. It seems as though he wants to turn from self-pity to self-reliance. Hughes's characters are often representatives of the black race, and in this sense, the bluesman is facing up to the difficulties imposed on blacks in a segregated America. Lines 23 and 24 The next two lines divide the two quotations of the bluesman's song from each other. This could also have been accomplished by inserting a blank line, so these lines must communicate some important aspect of the poem or else Hughes would not have included them. They report the bluesman's actions in between singing the two stanzas, realistically describing the actions of tapping his foot and playing the piano. However, the lines are filled with repeated words and an emphasis on repeated action that seems figurative, as if the repetition of action reflects the lives of black Americans, lived over and over again in oppression. Lines 25–30 Now the bluesman's tune is quite changed. Earlier, he had resolved to set aside his sadness, but in these lines he seems overwhelmed by it. The theme of repetition is continued by repeating two couplets with only slight variation, a device typical of, for example, the biblical Psalms, but supplanted in genuine blues songs by groups of three repeated lines. Hughes is drawing on spiritual traditions from within the black community other than the blues. The bluesman is worn down to the point where happiness seems impossible to him and he longs for death. Lines 31–35 Finally, the narrator continues to listen to the bluesman's performance, perhaps until dawn. The narrator does not describe his own actions following the end of the performance, but rather those of the bluesman. He goes to bed but cannot stop contemplating the melancholy subject of his song. At last, though, he sleeps like a dead man. Although that is a common metaphor for a particularly sound sleep, there is an intimate connection between death and sleep in the poetic tradition, and the closing of the poem suggests that the bluesman is finally worn down by his cares and surrenders to death. THEMES Black Culture “The Weary Blues” is a celebration of distinctive black culture through its music. However, it is even more a lament for the state of black culture in the America of the 1920s. Even in the North, blacks faced fairly strict segregation and had to exist apart from mainstream culture, in prescribed areas of large urban cities (later called ghettos after the neighborhood that Jews were restricted to in medieval Venice). Thus, blacks had to create a shadow world, with their own businesses and institutions that were allowed only limited interaction with the surrounding white society. Black artists and intellectuals were equally isolated. One of the great distinctions of Hughes's career was his breakthrough to popularity in the white world. Although Hughes had published several poems over a number of years in national magazines, when Vachel Lindsay “discovered” him, Hughes was treated as a completely unknown young poet because of the isolation of the two worlds. Hughes eventually found his solution to the artistic problems posed by segregation in the movement known as negritude. Hughes encountered this movement in Paris, where it was centered among the black expatriate community from the French colonies, but it became widespread among black intellectuals throughout the world, especially in Africa and the Caribbean. Its main idea was that blacks ought to make their own culture for themselves, without reference to the white communities that simultaneously surrounded and rejected them. Negritude did not reject Western culture, since its followers realized it was not possible and not even desirable to break out of the Western civilization that had conditioned their own experiences. The goal was to create a black culture that, if it had to be separate, would not be inferior. The term negritude means “blackness,” and Hughes himself coined the slogan “The negro is beautiful,” which in time became the 1960s saying “Black is beautiful,” as the idea percolated through popular culture. Although the international negritude movement eventually took its tone from the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes was its chief ambassador back to that environment. Hughes longed for freedom and equality as much as anyone else, but he realized it was not coming in his lifetime and consequently felt that blacks ought to make the most of their sheltered, limited cultural existence. “The Weary Blues,” however, is an early work, filled more with passion than reflection. It presents a vision of black culture as being ultimately doomed by its oppression. Music The blues is a form of music that first developed within the black community of the Deep South, about 1900. It was at this early date generally performed by individuals in part as an expression of deeply felt personal sadness, but always by professional or semiprofessional musicians as dance music or as entertainment in black bars and clubs (“juke joints,” as they were called). The musical form is indebted to the music of spirituals performed, usually, by the whole congregation of black churches, as well as to songs sung in the fields to regulate the physical activities of planting and harvesting. Although the African origin of this music is hotly disputed and often loudly insisted upon, no research has ever linked any aspect of the music to African roots, unlike many forms of music in the black cultures of the Caribbean, which have obvious and well-established African connections. The blues seems to be entirely the invention of the African American community, derived from the Protestant hymn tradition adapted from white culture. Hughes latched onto the blues because by the 1920s it was recognized by both blacks and whites as emblematic of black culture and because it expressed the deep melancholy that pervades his poem. Thus, the blues and spirituals descend from the same church music, and for Hughes the blues is able to express spiritual meaning. However, as Stephen C. Tracy points out in the essay “Langston Hughes: Poetry, Blues, and Gospel,” which appears in the collection Langston Hughes: The Man, His Art, and His Continuing Influence, such a view would not find easy acceptance in the conventional black culture of the time, desperately trying to become bourgeois: The fact that Hughes could throw one arm around spirituals and gospel music and the other around the blues simultaneously would seem remarkable, even blasphemous, in some circles, primarily Christian ones where the blues might be dubbed ‘the devil's music.’ For Hughes, however, they were one and the same thing, a spiritual expression of the inner life of black humanity. As he wrote in his autobiography The Big Sea, Like the waves of the sea coming one after another, always one after another, like the earth moving around the sun, night, day—night, day—night, day—forever, so is the undertow of black music with its rhythm that never betrays you, its strength like the heat of the human heart, its humor, and its rooted power.This music, this emotion, is The Big Sea of Hughes's autobiography. It is the weary blues. STYLE Meter “The Weary Blues” can be approached as two different parts in terms of its metrics: the narrative voice of the poem and the quotations from the bluesman. The frame seems, like much traditional poetry in English, loosely written in iambic pentameter; even the shorter lines, which have fewer than five feet, are still iambic. A foot in poetry is a set of stressed or unstressed syllables, and those sets are given special names depending on their pattern. An iamb is an unstressed followed by a stressed syllable, although English allows pretty free substitution of other feet such as trochees (stressed unstressed) and spondees (stressed stressed). Here, many of the longer lines should perhaps be read rather as tetrameter, or four feet per line, with some of the feet containing three (or even four) syllables, one stressed and two (or three) unstressed. In the opening lines particularly, Hughes uses various feet to achieve some rather spectacular metrical fireworks of the kind so favored by, for example, Edgar Allan Poe and, not coincidentally, Vachel Lindsay (Hughes's first white patron). In fact, it is difficult to read the opening lines of “The Weary Blues” and not have Poe's poem “The Bells” called to mind. Syncope is a device whereby the unstressed syllable of a word has to be elided (skipped over or condensed) to make the word fit the meter, for example, over becoming o'er. Although Hughes mentions musical syncopation in the first line, the poetic device of syncope is not actually used within the poem until the speech of the bluesman (note that eliding the f from of in line 8 mimics speech, but it does not alter the syllable count and is not syncope). There, however, the poetic syncopation is quite regular, occurring in all the contracted forms for am not, cannot, and going to that echo ordinary speech. There is another example of syncopation in the bluesman's first line, where a vowel that begins a word has to be elided after a word ending in a vowel. Syncopation as a poetic device is as old as Western poetry and occurs in the oldest Greek verse. Here, Hughes is suggesting the meter of blues music. However, he does not use many of the most obvious poetic markers of blues songs, such as an aaa rhyme scheme. Black Dialect The narrative voice of “The Weary Blues” speaks in standard English. The anonymous bluesman whose song is twice quoted in the poem speaks in dialect. Dialectical speech is not a mistaken form of some privileged, correct speech. One must imagine the development of language as akin to the branching of a genealogical tree, with a single source (Old English) giving rise to more and more descendants in each succeeding generation. It is not possible, on philological (language study) grounds, to privilege one of the descendant dialects over the other as being correct. It is, however, possible to attempt to privilege a single dialect of a language on political grounds, as had been done by the nineteenth century in all of the centralized European states, so that, for example, French is the dialect of Paris, Italian is the dialect of Florence, and English is the dialect of Oxfordshire. Mass education and, in the twentieth century, mass media help to enforce the favored dialect. Various English dialects continued to exist in the United States, since settlers in a specific location in the New World usually came from a certain particular area of the old. In the United States, the normalizing forces of education and the media tend to enforce a rather bland average of English dialects. The dialect spoken by many African Americans originated in the American South and is not very different from the speech of white southerners, which descends from the dialect of England's West Country. Contrary to popular wisdom, this form of English does not contain very many African elements (though a small number of words are of West African origin). The effect of giving the two speakers in “The Weary Blues” differing dialects is exotic, something that black and white readers alike in the 1920s thought black poetry ought to be. The dialectical elements are not very pronounced, since Hughes intends the piece to be intelligible to speakers of standard English like himself. The only repeated element is the dropping of the final g from the present participles (words endingin ing), which almost everyone does in informal speech. More interesting is what Hughes does to the vowel sound in the form he writes in place of the standard going. This form collapses the distinct o and i into a diphthong far more resonant than its standard counterpart, which Hughes presents with a w, though really, no ordinary English letter can quite record the sound as it is heard from many southerners, black and white. Ain't is a standard form in English speech and is exiled only from the most artificially perfect and formal dialects. Similarly, the double negative, in almost all English speech, serves the same function as in other European languages, to intensify the negative, and it is overly fussy to insist that they cancel each other out to become a positive. The presentation of the bluesman's dialect is light and subtle, but it left Hughes's audience in no doubt that black dialect was being invoked. The word blue as it is used in “blues music,” denoting sadness, goes back to medieval usage in English. It is a metaphor based on the livid color of corpses, with the color of pale skin in death standing for sadness and melancholy. CRITICAL OVERVIEW There is some controversy over the inspiration of “The Weary Blues” because of Hughes's lack of clarity on the subject. Stephen C. Tracy, in “Langston Hughes: Poetry, Blues, and Gospel—Somewhere to Stand,” repeats an often-asserted statement: “[Hughes] recalled the first time he heard the blues in Kansas City on the appropriately named Independence Avenue, which provided him with material for his ‘The Weary Blues.’” This seems to be the majority opinion among Hughes scholars, but it arose from a basic confusion in Hughes's autobiography, The Big Sea. He indeed says of the bluesman's song that it was “the first blues verse I'd ever heard way back in Lawrence, Kansas, when I was a kid.” In a 1964 interview for a Kansas City newspaper, quoted by Tracy, Hughes changed his story so that he heard the inspirational song in Kansas City on Independence Avenue. In the poem itself, though, Hughes claims to have heard the song on Lenox Avenue in Harlem, a detail that seems to be confirmed as autobiographical elsewhere in The Big Sea: “That winter I wrote a poem called ‘The Weary Blues,’ about a piano player I heard in Harlem.” It is conceivable, of course, that while the Harlem piano player may have inspired the poem, Hughes elected to use the lyrics he had heard long before. Among more recent work on “The Weary Blues,” Edward E. Waldron, in the Negro American Literature Forum for 1971, derives the themes of loneliness, despair, and frustration that predominate in Hughes's work as a whole from the blues, as exemplified in the blues song embedded in “The Weary Blues.” David Chinitz, in the 1996 issue of Callaloo, points out that the traditional structure of Hughes's early poems, especially his insistence on closure (Hughes wrestled with “The Weary Blues” for months to find just the right ending) stand in contrast to the relatively amorphous (free-form) structure of traditional blues, which often uses a lack of closure to create irony. While “The Weary Blues” seems assured of a prominent place among Hughes's works and in their scholarly reception, Karen Jackson Ford, in a Hughes anthology edited by Harold Bloom, argues that this poem and others of his most discussed works, such as “The Negro Speaks of Rivers,” ought to be de-emphasized in favor of the poetry that Hughes composed for the mouth of his character Jesse B. Simple, a black Everyman about whom Hughes wrote in his syndicated newspaper column for many years. While most critics dismiss these works as satire, Ford sees them as a more authentic black voice. Source Citation (MLA 7th Edition): "The Weary Blues." Poetry for Students. Ed. Sara Constantakis. Vol. 38. Detroit: Gale, 2011. 275-298. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 6 Feb. 2014.