English poetry coursework...YEAH!.doc

advertisement

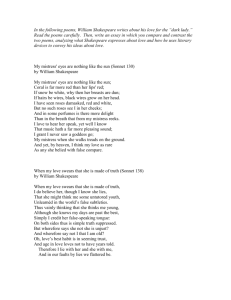

Amrou Al-kadhi Compare the representation of the lover’s voice in Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’ and Browning’s ‘Porphyria’s Lover.’ When people think about love poems, there are usually certain things that they would expect to read. A conventional love poem often portrays a person feeling very passionate for their lover. The one being admired is usually represented as extremely beautiful and elegant; they are compared to angels, the beautiful aspects of nature, jewels and stars, while the lover is normally of a lower status. Since the lovers can be very passionate in such poems, a lot of sensual and sexual imagery is used. Given the fact that most published poets before the twentieth century were men, love poems are often from the male point of view. In a love poem, the lover can feel amour, lust, and sometimes despondency because of their lover. Although both ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ and, ‘Porphyria’s Lover,’ include some of these conventions, both poems include images of death, and other things a reader would not expect to find in a love poem. Andrew Marvell’s poem, ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ which was written in the seventeenth century, shows a man trying to seduce his mistress by arguing his points on why they should make love. Robert Browning’s poem, ‘Porphyria’s Lover,’ which was written in the nineteenth century, is a poem about a man so deeply in love with a woman named Porphyria, that he strangles her to preserve the moment when he realises that she truly loves him. Even though both poems share certain similarities, it is interesting to compare them, as there is a sharp contrast between both the speakers and contents of the poems. Andrew Marvell’s poem, ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ begins in a jovial mood, following the traditions of a love poem; a contrast to the tempestuous mood that is created in the beginning of ‘Porphyria’s Lover.’ ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ begins with a man flattering his mistress, and in doing so, he creates a mood of love and happiness. The speaker of the poem compliments his mistress by saying, ‘Thou by the Indian Ganges’ side/ Shouldst rubies find’ (5-6). At the time of writing, travelling abroad was a very exciting activity, which makes the reference flattering. Travelling had just started to become popular, but only very respected and wealthy people were able to visit other countries, so the fact that the man of the poem tells his mistress that she should be in such an exotic country, makes her seem extremely beautiful and wealthy *. In fact, some typical features of metaphysical poetry are references to foreign travel and colonialism. The word ‘rubies’ really allows the reader of the poem to imagine the lover’s beauty, because a ruby is a precious and spectacular object that is associated with exquisiteness. A ruby is also red, which leads the reader to imagine that the man is very passionate for his mistress. This is why the word is so successful in helping to create an amorous mood at the beginning of the poem. The speaker of the poem tells his mistress that he would, ‘love [her] ten years before the flood’, (8) and, ‘till the conversion of the Jews’ (10). Although a reader may interpret these compliments as insincere, as they are so exaggerated, these conventional hyperboles show the reader that this man loves his mistress very much, which is why he is flattering her to such an extent. These biblical metaphors also add to the embellishment of his love for his mistress, because the bible was, and still is to some people, a very important book, and at the time of writing, religion was very important. If this hyperbole was used in an unpleasant way, then it may have been offensive, however, because the speaker uses this biblical reference as an exaggerated form of flattery, the compliment is more serious. Different from, ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ starts in a sinister mood. Robert Browning employs pathetic fallacy at the beginning of the poem, to tell the reader that the speaker is, ‘sullen,’ ‘spite[ful],’ and ‘vex[ed].’ The speaker claims that the wind is ‘sullen,’ but it is really him who is in a miserable mood. He states that the wind ‘tore the elm-tops down for spite’ (3), which generates the image of a horrendous storm, tearing down trees viciously. This implies that it is the speaker who is filled up with rage. The word ‘spite’ clearly shows us this, as it suggests that he is seeking revenge over his lover, Porphyria, because she is late to see him, which has angered him greatly. Finally, the word ‘vex’ is useful in telling the reader that the man has been aggravated, like a strong wind stirring up a lake, because his lover is not with him. The word makes the man seem as if he is looking for a fight with his lover. The line, ‘I listened with heart fit to break’ (5), once more implies that the speaker is very upset, because he is not with Porphyria. In both poems, it is evident that both men desire to have their mistress. However, at the beginning of each poem, the women seem to be more dominant, so the men feel that they need to assert power over their mistresses; there is an obvious power struggle between both genders in each poem. * In ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ the mistress is said to start off behaving with ‘coyness,’ which makes her seem more dominant over her lover, as she is teasing him, and acting as if she does not want to make love with him. Even though this is only the man’s perception of her actions, he still seeks power over his mistress. At the time of writing, men were normally much more dominant in relationships, which may be why the man in the poem wants control. In ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ the speaker of the poem claims that he will adore each of his mistress’ breasts for two hundred years. He says that he will spend thirty thousand years loving the rest of her body, and like a typical love poem, he claims that he will spend the longest time admiring her heart. All this flattery about loving her for an endless amount of time, shows that the man in the poem would like to have his mistress forever. The speaker may also be using these hyperboles to comfort his mistress, so that she is not worried that he will leave her once they have made love. The speaker then goes on to explain, somewhat like a lawyer, that it would not be possible to adore her for this long, as everyone will die. He says, ‘But at my back I always hear/ Time’s winged chariot hurrying near’ (20-22). He then argues, ‘The grave’s a fine and private place,/ But none, I think, do there embrace’ (31-32). With this argument and classical imagery, he is making his mistress think that she should have sex with him, because if she does not, she will be lonely after she dies, not having had sex with him. The word ‘embrace’ is used by the speaker to convince his lover to having sex with him; the word makes a person think of intimacy and love, and because the speaker suggests that she will not receive any warmth in the grave, makes her believe that she should seize the moment to be close with her lover now. The line ‘Deserts of vast eternity’ (24), is also used by the man to scare his mistress. This is because the imagery of loneliness and dryness will frighten her into wanting to have sex with him. This imagery is also somewhat blasphemous, as the speaker is implying that there is no life after death, and since this poem was written at a time when many people were religious and believed in the after life, this insinuation could be insulting. When the speaker then says, ‘And your quaint honour turn to dust’ (29), he creates the image of her body decaying away completely, which again frightens his mistress into wanting to make love with him. After he scares his mistress, the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ makes sex sound like an exciting activity. He tells his mistress that they will make love like ‘amorous birds of prey’ (38), and that they will ‘tear [their] pleasures with rough strife’ (43). The quotations show how the speaker embellishes the roughness of sex, which persuades his mistress into wanting to have sex with him, as he has made the activity seem very passionate and full of life. The word ‘prey’ implies animosity, which once more shows how the speaker makes sex seem almost violent. The words ‘tear’ and ‘rough’ once more make sex seem like a very fiery activity. The line, ‘Thorough the iron gates of life’ (44), is the speaker telling his mistress to “seize the moment,” which is a persuasive technique used by the man, as it makes the woman not want to waste life, and not regret things she has not done These logical arguments that the speaker presents to his mistress, do not follow the conventions of a love poem. This is because love poems are supposed to be very passionate, whereas this poem is somewhat metaphysical. Examples of this can be seen at the end of each stanza, as the speaker summaries his main points with rhyming couplets. For example, at the end of the first stanza, the speaker claims more sincerely, ‘For, Lady, you deserve this state,/Nor would I love at lower rate’ (18-20), which rounds of all the compliments he was giving - these summaries are very logical for a love poem. Through his arguments, the speaker of, ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ tries to win over his mistress, so that he can make love to her. Similar to ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ the woman in ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ starts with more control in her relationship. She leaves her lover waiting in his cottage, and decides when she will come to see him. This dominant characteristic that Porphyria has, can once more be seen when she initiates intimacy with her lover; she lets ‘her damp hair fall’ (12), and ‘she sat down by [his] side’ (14), while he remains upset. This is quite untraditional for a Victorian woman; women at that time were expected to remain celibate until marriage. It is unknown whether Porphyria is married, but the fact that she may be involved in an illicit affair, would have been seen as very wrong at the time of writing. Porphyria’s lover is made to feel powerless, as he is possibly of a lower class than her. When Porphyria ‘glided’ in at the beginning of the poem, the reader can get the impression that she is an elegant woman. The line ‘from pride, and vainer ties dissever,’ indicates that Porphyria is an upper class women. She is said to have ‘vainer ties,’ which suggests that seeing this man, is as if she is disobeying her routes, implying that she is a woman of a higher class than her lover. The word ‘pride’ is also used, which indicates that Porphyria might be too proud to be with a man so different from the people she is expected to associate with, and the word ‘dissever,’ makes it seem as if she wants to be cut free from these ‘vainer ties,’ and be with her lover forever. The man in ‘Porphyria’s Lover,’ is so deeply in love with Porphyria, that the moment he realises that she ‘worshiped [him],’ he strangles here with her hair, ‘three times her little throat around.’ The reason that he does this, is because he wants to preserve the feeling that he had when he realised Porphyria loved him very much. Once he has killed Porphyria, the speaker still tries to be in control over her, when he props ‘her head up as before,’ because this shows how is trying to be dominant over Porphyria’s dead body, and have her in the position that he wants. t is intriguing how the man in ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ uses death as a new beginning to his and Porphyria’s relationship, whereas the man in ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ talks about death as the end, where his mistress will not be able to be with him. Although a contrast to the methodical way that the speaker in ‘To His Coy Mistress’ uses to have power over his lover, the speaker in ‘Porphyria’s Lover,’ still, like in the other poem, seeks control and power over his mistress. In both poems, the women are represented through the speaker’s words; the men of each poem project their own feelings and desires onto the women, and we are not told of the women’s true emotions. The speaker in ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ very cleverly manipulates his mistress into believing that what he says is true. For example, he claims to her that she is acting with ‘coyness.’ He is saying that she is teasing him, and refusing his advances, to make her feel shameful about her manner, therefore, persuading her to make love with him. However, the actions of the mistress are not necessarily coy, because at the time of writing, remaining a virgin until marriage was what a woman was expected to do; a reader at the time the poem was written, may call the mistress honourable or noble. The speaker’s projection of his own desires onto his mistress can be seen when he says, ‘And while thy willing soul transpires,’ (35). The speaker uses the word ‘willing,’ to manipulate his mistress into believing that she does want to make love to him; he is trying to make her feel the way that he does. This can once more be seen when the speaker mentions that at ‘every pore’ there are ‘instant fires’ (36). He is implying to here that she is blushing because of him, suggesting that she does feel passionately towards him, and does want to make love to him. The word ‘fires’ also represents passion, and this word is used so that the mistress in the poem is made to believe that she does feel this emotion towards her lover. * What is particularly interesting in ‘Porphyria’s Lover,’ is the speaker’s interpretation of Porphyria’s actions. When Porphyria tries to get closer to her sulking lover, by removing items of clothing, letting her hair down, moving closer towards him, and then looking him straight in the eye, the speaker claims that he was ‘Happy and proud; at last I knew/ Porphyria worshiped me’ (32-33). The fact that he is overjoyed because he has this woman’s love, tells us that Porphyria must be a great and worthy woman. However, it is questionable whether Porphyria ‘worshiped’ her lover, as the poem is only from the male point of view; ‘worshiped’ is a strong word, and the speaker may be embellishing the love that Porphyria feels for him. Therefore, it is unsure whether Porphyria feels this emotion towards her lover; she may feel some affection towards him, or may just want sex. When Porphyria is killed, it seems that the speaker feels that this was the right thing to do. Halfway through line fourty one, the speaker says he ‘strangled [Porphyria].’ The caesura that Robert Browning uses in this line after he mentions that the speaker strangles his lover, is very clever. This is because it makes the fact that the speaker killed Porphyria, seem very straightforward and emotionless, which depicts how the speaker feels that he acted rightly. After the caesura, the man just carries on speaking to the reader, telling a reader that he feels little remorse for his actions, and feels what he did was correct. Even though he has strangled her, the speaker feels that this was what Porphyria wanted, and in some respects, feels that she still loves him. He claims that her cheek, ‘Blushed bright beneath my burning kiss’ (48). The speaker acts as if Porphyria has not been strangled, and feels her red cheeks are a result of her blushing because she loves him. However, what the speaker believes to be passion, is merely the blood-filled cheeks of the now strangled Porphyria. He even says that she is ‘smiling,’ indicating that he feels she is happy because he has murdered her. This shows evidence of the male projecting his own desires onto Porphyria, even though she is dead. What is most astonishing, is when the speaker says ‘So glad it had its utmost will’ (53), and ‘her darling one wish would be heard’ (57). The speaker is primarily saying that Porphyria wanted to be killed, because she wanted to be with him forever. However, it is obvious that Porphyria did not want to be with her lover forever by being murdered. The words, ‘will’ and ‘wish,’ show that the speaker feels that Porphyria desired to be with her lover for the rest of her life; the only way that the man could offer this, however, was by killing her. Through the language and thoughts of both the speakers of the poems, their complex personalities are revealed. In ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ the reader can learn that the speaker is a witty, intelligent, and teasing person. The way in which he presents his argument shows intelligence. He tactfully flatters his mistress, and tells her that he would adore her forever if possible, so that she is not worried that he would leave her after sexual intercourse. He then scares his mistress by telling her that everyone will die eventually, and will receive no love or warmth in the grave, which makes the lady of the poem want to “seize the moment” that she has with her lover. This rational argument shows the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ to be cunning, which makes the poem somewhat metaphysical. The man’s wit is displayed through the double meanings of some of his phrases. When he states, ‘My vegetable love should grow’ (11), a reader may interpret this as the man discussing how his love will continue growing for his mistress. However, another interpretation of this, is that he is making a reference to phallic imagery, and is implying that he will be sexually aroused. Another example of this, is when he claims, ‘And your quaint honour turn to dust’ (29). Once again, he may just be saying that her attractiveness will deteriorate in the grave. However, he could be using the word ‘quaint,’ because it sounds similar to a slang term for a female sexual organ. The reader of the poem also comes to learn of the man’s playful demeanour. The hyperboles that the speaker uses to flatter his mistress show this, for example, he tells his mistress that he would, ‘love [her] ten years before the flood,’ and, ‘till the conversion of the Jews’ (8 and 10). He is completely embellishing his love for his mistress, as the flood was thousands of years ago, and we know that the Jews will never convert. These gently satiric remarks show him to be not only complimentary, but slightly teasing. As a contrast to the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ the speaker of ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ is an isolated, powerless, psychotic and blasphemous man. The poem starts off when the man is all alone, waiting for his lover. The weather described reflects the mood that he is in (pathetic fallacy); the words ‘sullen,’ ‘spite,’ and ‘vex’ help portray the personality of the speaker. Already, by the beginning of the poem, we learn that his mistress decides when to see him, showing him to be powerless. We can again see the lack of power that the man has, because Porphyria is the one who is initiating the intimacy, showing her to be in full control. This also shows the speaker to lack confidence, as he is not the one able to be more dominant; it is Porphyria who initiates sex. This trait of the speaker is revealed when Porphyria enters the cottage, because, from the first stanza, we learn that he is ‘spite[ful],’ and ‘vex[ed],’ and seeks revenge. However, when Porphyria enters, he is not able to tell her what he really feels. The fact that he actually murders Porphyria to preserve the moment of love between them, indicates that the man is not only violent, but psychologically disturbed; a sane person would not kill their lover so that they could be with each other for ever. This mentality is displayed further, when the speaker confuses his strangled lover to be blushing, and treats her as if she has not been murdered. He even props up her head on his shoulder, and sits with her all night. However, the reader is able to see a little bit of sanity in the speaker, when he claims, ‘I am quite sure she felt no pain.’ This subtly suggests that he feels a little culpability for the murder he has committed, as the word ‘quite’ suggests that he is a little unsure of what he has done, and that he is trying to justify his actions. This is again seen when he ‘warily’ opens Porphyria’s eye lid. This word suggests that he is fairly worried that Porphyria is still alive, indicating that he feels a little bit guilty for his actions. Finally, the final line of the poem, ‘And yet God has not said a word,’ shows the character to be blasphemous, and perhaps over confident in his actions. This is because at the time of writing, religion was very important, and the fact that the speaker claims that God has not prohibited what he has done, would have been very offensive, and still would be to many religious people. Through the speakers’ actions and words, we can see conventions of a love poem. The fact that that the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ is very flattering, is typical of love poem, as love poems normally contain a lot of compliments, and are often very romantic. Even with, ‘Porhphyria’s Lover,’ the fact that the speaker is depressed, and listens ‘with heart fit to break,’ is not unusual for a love poem. Several love poems show lovers infatuated and despondent because of their lover. It is the fact that the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ uses images of death to scare his mistress, and that the speaker of ‘Porphyria’s Lover’ murders his mistress to preserve their love, is what is unconventional of both poems. Even though several love poems are quite depressing, very few are as sinister enough to incorporate murder, or use death as a threat. What is also quite unconventional of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ is the way he approaches his mistress. Lovers trying to woe their mistress are often romantic, and not logical and methodical, which is apparent in the speaker of ‘To His Coy Mistress,’ in the way he approaches his argument. The blasphemy when the man tells his mistress that there is no life after death, is also quite shocking in a poem of this nature, which can also be seen in ‘Porphyria’s Lover’, when the man tells the reader that god has not prohibited the murder of an innocent woman. Overall, both the speakers are different in the way they approach their desires to have their mistresses, and they also have many different characteristics. However, both the speakers have the same objective, and that is to possess their mistresses.