Text Version

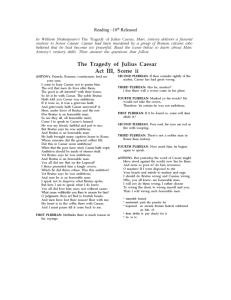

advertisement

Commentary #1 (ETEC540) for Teresa Dobson Mark Antony's Funeral Oration from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar On Oct. 30, 1974, in Kinshasa, Zaire, Muhammad Ali defeated George Foreman to regain the world heavyweight title against all odds. Ali was older than Foreman, smaller in physical stature and had only recently returned to professional boxing from an enforced three-year layoff due to his unpopular (in the States, at least) draft-dodging status. The experts and public alike felt that time had seriously eroded his fighting skills. (HBO). Nonetheless, he triumphed. In 44 B.C. (Wright 1959: x) Mark Antony, a Tribune in the Roman army, boxed himself out of a similar corner against Marcus Brutus, a conspirator against Julius Caesar and also one of his assassins. Antony was Caesar's close friend and, naturally, was at risk while Caesar's assassins were abroad. The conspirators reluctantly spare him because Brutus claims Antony is "… but a limb of Caesar" (II ii 174). As such, he is granted permission by Brutus to speak at Caesar's funeral because, as Brutus tells the other conspirators, "It shall advantage more than do us wrong." (III i 261). He cautions Antony, "You shall not in your funeral speech blame us" (III i 265). Antony agrees but, just as Ali employed his "Rope-A-Dope" strategy more than 1,900 years later to achieve victory, Antony comes off the ropes swinging with his famed funeral oration, to capture the sympathy of Rome's citizens and to set in train a series of events that, ultimately, brings down the conspirators. The oration, as befits its name, exhibits a number of characteristics, described by Ong, that are associated with orality. Firstly, Antony speaks in verse, which makes his speech more memorable, since rhythm is a powerful mnemonic device (Ong 2002: 3435). Compare his opening line: Friends, Romans, countrymen; lend me your ears; I come to bury Caesar, not to praise him. (III ii 80-81) with the opening line of the preceding speech, which is delivered, in prose, by Brutus: Romans, countrymen, and lovers, hear me for my cause, and be silent, that you may hear. (III ii 14-15) The powerful rhythm of Antony's words seems much more likely to lodge them in the minds of his audience and, thereby, sway them. His use of the word "friends", which is subsequently repeated four times, personalizes his rhetorical style and achieves "close, sympathetic, communal identification" (Ong 2002: 45). Anthony also employs the oral technique of being "redundant or 'copious'" (Ong 2002: 39) to hold the attention of his listeners. He repeats his sarcastic reference to Brutus and the other conspirators as being "honorable men" eight well placed times, like a series of stinging jabs, and, equally sarcastically, five times mentions Caesar's supposed "ambition", which is the justification Brutus offered for killing Caesar (III ii 27). By way of comparison, Brutus repeats himself only three times, sounding, for the most part, awkward, as in the above example, or when he says. "… for him have I offended (III ii 30-34). Antony's sarcasm, along with his sorrow and anger, appeals to the emotions of 2 the crowd rather than to their reason, an oral characteristic Ong (2002: 45) refers to as "empathetic and participatory rather than objectively distanced." Antony does not ask the citizenry to contemplate, as Brutus does, the abstraction (more suited to writing) of what it means to be a citizen of Rome (III ii 29-34) but instead skillfully reminds them of the story of Caesar's life: how he filled Rome's coffers with ransom (III ii 96-97), how he refused a crown three times (III ii 103-104), how "… he overcame the Nervii" (III ii 184) and how he trusted Brutus and yet was betrayed by him (III ii 192-194). These are all vivid images for Antony's audience and are easier to imagine than ambition. Ong (2002) would call these images "situational rather than abstract" (49). Antony enhances this engagement by asking his audience questions: Did this in Caesar seem ambitious? (III ii 97) You will compel me then to read the will? (III ii 168) When comes such another? (III ii 264) During his narrative, Antony plucks his listeners' heartstrings by showing them Caesar's mutilated body rather than merely describing it: If you have tears, prepare to shed them now (III ii 180) And he makes them angry by describing the loss of his friend and his supposed inability to do Caesar justice: But were I Brutus, 3 And Brutus Antony, there were an Antony Would ruffle up your spirits, and put a tongue In every wound of Caesar that should move The stones of Rome to rise and mutiny. (III ii 237-241) Finally, he delivers the knockout punch — he appeals to their self-interest: Here is the will, and under Caesar's seal. To every Roman citizen he gives, To every several man, seventy-five drachmas. (III ii 253-254) The plebians can understand this, just as they can understand that Caesar, also in his will, has left them: … all his walks, His private arbors, and new planted orchards, (III ii 259-260) These things are closer to their lifeworld — another oral characteristic — (Ong 2002: 4243) than abstract notions of citizenship. And, once again, Antony masterfully uses repitition to hold his listeners in suspense, mentioning the will on four occasions before actually disclosing its contents. Each time he mentions it his tone becomes increasingly, as Ong (2002: 43-45) would say, agonistic. He calls the conspirators "traitors" (III ii 208), suggests "mutiny" (III ii 241) and praises Caesar ever more fulsomely because, "Colorless personalities cannot survive oral mnemonics" (Ong 2002: 69). A lesson Muhammad Ali (far from being a literate man) learned well. While George Foreman told the public and the press that all he wanted was "to win the fight", Muhammad Ali led the 4 spectators in Zaire at every opportunity in the chant, "Al-i, bom a ye! Al-i, bom a ye!" (Ali, beat him! Ali, kill him!) (Hennessey 1999: 98) a phrase in Swahili (Ali 2003), an African language that was originally oral. Similarly, Mark Antony urges his crowd on, until, like baying dogs, they break free, cry havoc and, ultimately, win for him the title of Triumvir. References 1. Ali, H. O. A brief history of the Swahili language. Retrieved July 16, 2003 from http://www.glcom.com/hassan/swahili_history.html 2. HBO. (2001). Muhammad Ali: The greatest collection. DVD. 3. Hennessey, J. (1999). Muhammad Ali: The greatest. London: PRC Publishing. 4. Ong, W. J. (2002). Orality and literacy: The technologizing of the word. New York: Routledge. 5. Wright, L. B. (1959). Introduction. Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare. New York: Washington Square Press. 5