5.2 The Prohibition Experiment

advertisement

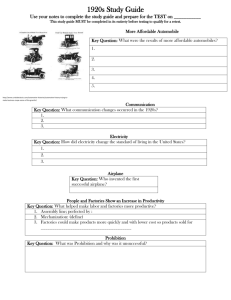

Name __________________________ Date: ________________ Section: 11.1 11.2 (circle one) U. S. History II HW 5.2: Prohibition Instructions 1. Carefully read and annotate this article for MAIN IDEAS 2. Identify the following key terms (including date, definition, and significance): a. Consumer culture (use your lecture notes) b. Prohibition c. 18th Amendment d. Bootlegger e. Speakeasy f. Al Capone g. 21st Amendment 3. Complete the chart below. Use the reading to summarize, in your own words, the causes (why did Prohibition happen?) and effects (what effect did Prohibition have of American society?) of Prohibition. You should have at least 4 separate points on each side: Causes of Prohibition Effects of Prohibition The Prohibition Experiment Source: Gerald A. Danzer et al., The Americans: Reconstruction through the 20th Century (Boston: McDougal Littell). One vigorous clash between small town and big-city Americans began in earnest in January 1920, when the Eighteenth Amendment went into effect. This amendment, which prohibited the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages, launched the era known as Prohibition. Reformers had long considered liquor a prime cause of corruption. They thought that too much drinking led to crime, wife and child abuse, accidents on the job, and other serious social problems. Industrialists, such as Henry Ford, were also concerned about the impact of drinking on labor productivity. The churchaffiliated Anti-Saloon League had led the drive to pass the prohibition amendment. The Women's Christian Temperance Union, which considered drinking a sin, had helped push the measure through. Advocates of Prohibition argued that outlawing drinking would eliminate corruption and help Americanize immigrants. Even before the 18th Amendment was ratified, about 65% of the country had already banned alcohol. In 1916, seven states adopted anti-liquor laws, bringing the number of states to 19 that prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. America's entry into World War I allowed many to defend national Prohibition as a war measure. Prohibition seemed patriotic since many breweries were owned by German Americans. In December 1917, Congress passed the 18th Amendment. A month later, President Woodrow Wilson began partial prohibition to conserve grain to make bread for soldiers and not liquor. Beer was limited to 2.75% alcohol content and production was held to 70% of the previous year's production. In September, the president issued a ban on the wartime production of beer. The wording of the 18th Amendment banned the manufacture and sale (but not the possession and consumption) of "intoxicating liquors." Many brewers hoped that the ban would not apply to beer and wine. But Congress was controlled by the drys, who advocated a complete ban on alcohol. A year after the ratification, Congress enacted the Volstead Act, which defined intoxicating beverages as anything with more than 0.5 percent alcohol. This meant that beer and wine, as well as whiskey and gin, were barred from being legally sold. Enforcing Prohibition At first, saloons closed their doors, and arrests for drunkenness declined. But the effort to stop Americans from drinking was doomed. In the aftermath of World War I, many Americans were tired of making sacrifices; they wanted to enjoy life. Most immigrant groups did not consider drinking a sin but a natural part of socializing, and they resented government interference. Prohibition’s fate was sealed by the government, which failed to budget enough men and money to enforce the law. The Volstead Act established a Prohibition Bureau, but the agency was underfunded. The job of enforcement involved patrolling 18,700 miles of coastline, tracking down illegal equipment, monitoring highways for truckloads of illegal alcohol, and overseeing the industries that legally used alcohol. The federal government never had more than 2,500 agents enforcing the law. A few states did try to help out. Indiana banned the sale of cocktail shakers and hip flasks; Vermont required drunks to identify the source of their alcohol. Congress originally estimated that enforcement would cost $5 million; several years later, the government estimated enforcement would cost $300 million. Effects of Prohibition Prohibition did briefly benefit public health. The death rate from alcoholism was cut by 80 percent by 1921, while alcohol-related crime dropped. Nevertheless, seven years after Prohibition went into effect, the total deaths from impure liquor reached approximately 50,000, and there were many more cases of blindness and paralysis. Also, drinkers went underground, flocking to hidden saloons and nightclubs known as speakeasies (because when inside, one spoke quietly—“easily”—to avoid detection), where liquor was sold illegally. Speakeasies could be found everywhere—cellars, office buildings, tenements, hardware stores, etc. To be admitted to a speakeasy, one had to use a password, such as “Joe sent me,” or present a special card. Inside, one would find a mix of fashionable middle-class and upper-middle-class men and women. In 1927, there were an estimated 30,000 illegal speakeasies--twice the number of legal bars before Prohibition. Many people made beer and wine at home. Before long, people grew bolder in getting around the law. Hardware stores sold cheap stills, and books and magazines explained how to distill liquor from apples, from watermelon, even from potato peelings. In Cleveland, an estimated 30,000 city residents sold liquor during Prohibition, and another 100,000 made home brew or bathtub gin for themselves and friends. Since alcohol was allowed for medicinal and religious purposes, prescriptions for alcohol and sale of sacramental wine (used in church services) skyrocketed. People also bought liquor from bootleggers (named for a smuggler’s practice of carrying liquor in the legs of boots), who smuggled it from Canada, Cuba, and the West Indies. They sold the liquor from ships anchored in international waters. Then they bribed policemen and judges to let them operate freely. The business of evading the law became a sort of national sport. People had little respect for law enforcement. Prohibition not only generated disrespect for the law but had other harmful effects as well. Most serious was the flow of money out of lawful businesses and into fast-growing organized crime. In nearly every major city, underworld gangs seized the opportunity to make and sell liquor and pocket huge profits. Chicago became notorious as the home of Al Capone, a gangster whose bootlegging empire netted over $60 million a year. Capone’s organization reportedly had half the city’s police on its payroll. Capone took control of the Chicago liquor business by killing off his competition. During the 1920s, headlines reported 522 bloody gang killings and glamorized bootleggers like Capone. Men like him served as models for the central characters in films like Scarface. They became part of the folklore of the decade. Conclusion By the mid-1920s, only 19% of Americans supported Prohibition. The rest, who wanted the amendment changed or repealed, pointed to a rise in crime and lawlessness that they considered worse than the problem prohibition had set out to fix. Rural Protestant Americans, however, defended a law that they felt strengthened moral values. The 18th Amendment remained in force until 1933, when it was repealed by the 21st Amendment. Even today, debate about the impact of Prohibition rages. Critics argue that the amendment failed to eliminate drinking, made drinking more popular among the young, spawned organized crime and disrespect for the law, encouraged solitary drinking, and led beer drinkers to hard liquor and cocktails. The lesson these critics derive: it is counterproductive to try to legislate morality. Opponents argue that alcohol consumption declined dramatically during Prohibition--by 30% to 50%. Deaths from cirrhosis of the liver (a disease caused by alcohol consumption) for men fell from 29.5 per 100,000 in 1911 to 10.7 per 100,000 in 1929. Was Prohibition a "noble experiment" or a misguided effort to use government to shape morality? Even today, the answer is not entirely clear. Alcohol remains a serious cause of death, disability, and domestic abuse. It was not until the 1960s that alcohol consumption levels returned to their pre-Prohibition levels. Today, alcohol is linked each year to more than 23,000 motor vehicle deaths, domestic violence, and to more than half the nation's homicides.