Derby Ridge School

advertisement

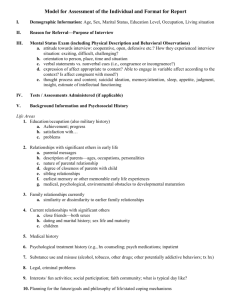

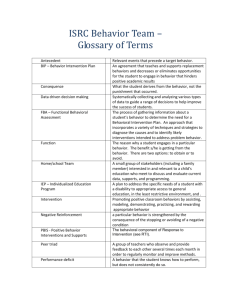

Overview All kids rebel or misbehave occasionally, but this behavior alone does not constitute what is called a behavior disorder (or conduct disorder). In order to be classified as having a behavior disorder, the child or teen must have a pattern of hostile, aggressive or disruptive behaviors over an extended period of time. Examples of specific conditions include self-injury, temper tantrums, fighting, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), cheating, and swearing. Warning signs that a child or teen may have a behavior disorder include: Harming or threatening themselves, other people or pets Damaging or destroying property Lying or stealing Not doing well in school Skipping school Early smoking Drinking or drug use Early sexual activity Frequent tantrums and arguments Consistent hostility towards authority figures It should be noted that boys are more likely to be diagnosed with conduct disorder than girls. Boys are more likely to show aggressive behavior, threats, vandalism, and confrontational behavior. Girls, on the other hand, are more likely to lie, skip school, run away, and shoplift. Compared to boys, they are also less confrontational in their behavior. Although there are a variety of methods that are used to treat behavior disorders, PBS (Positive Behavior Support) will be the specific treatment focus for this paper Treatment & Intervention Positive Behavior Support (PBS) is a behavioral and academic intervention model which can be implemented at all grade levels. PBS is founded on the philosophy that Prevention is most effective and efficient Graduated interventions should be designed to match the level of behavioral need Interventions should be educative vs. punitive Team based approach Identifies, teaches and reinforces expectations Teaches social/behavioral skills as necessary for positive life outcomes Interventions need to be sustained overtime to make positive impacts on students The PBS system was developed out of public health and disease prevention. Intervention and need levels are illustrated through the use of a triangle, with the bottom addressing universal interventions, provided to all students. These interventions are preventive and proactive and will address the needs of 80 to 90 percent of the student population. An example of a green zone intervention would be to provide positive re-framing of desired behaviors, instead of telling students what not to do. For example if a school goal is safety, instead of telling students not to run in the hallway, a school wide expectation might be to be safe. Research indicates that 3-5 behavioral expectations that are positively stated, easy to remember, and significant to the students and the school are best, National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports, U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs, www.pbis.org The Second level of the pyramid addresses “yellow zone” students. At this level targeted group interventions are provided for 5 to 10 percent of the students who are at some risk. Interventions are developed to address behavioral issues of groups of students with similar problem behaviors or which appear to occur for the same reasons, such as work avoidance or attention seeking. A yellow zone intervention might be a Check in Check Out (CICO), where a student checks in briefly with a designated staff member each morning and receives a behavior tracking sheet, the staff member can provide school supplies and monitor student affect and at the end of the day, the student returns to the staff member and turns in their tracking sheet. The third level of the pyramid is designed to address the individual. At this point a team of staff and parent or guardian (if possible) should meet to develop a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA). The first step in conducting a functional assessment is for the team to identify and agree upon the behavior that most needs to be changed. Students often exhibit a spectrum of difficult behaviors, so it will be necessary to develop a prioritized list, so the most severe behaviors can be addressed first. At times it will be necessary to ignore and not respond to irritating but non-dangerous behaviors, particularly when the student is working on correcting more severe behaviors. The second step is data collection on the occurrence of the targeted behavior, identifying not only its intensity and frequency, but also looking at the context, (the when, the how, and the where) of the targeted behavior. The third step is to develop, from the data collected, an hypothesis about the purpose and the function of the student's behavior. Next and the team will need to develop an intervention based on the understanding of the triggers and supports for the behavior's occurrence. After the intervention been implemented for a period of time, the team will need to test their first hypothesis. The intervention may be effective and the behavior might decrease or disappear, however, if desired changes do not occur, the team my want to discuss whether the intervention may need to be paired with other modifications or rewards to increase its effectiveness. They should look at whether the intervention reduced the problem behavior enough to continue? If not, what other interventions or strategies should be considered. It may be necessary to reevaluate whether the team’s hypothesis is on target. OSEP Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports <pbis.org 2 Classroom Guidance & Lessons Teaching Social Skills With Integrity What Does it Mean to Teach Social Skills With Integrity? A school-wide approach to teaching social skills with integrity is when all staff demonstrate, explain, and practice social skills within and across multiple school settings daily. This level of implementation would require all staff in the building to understand their role in teaching social skills. Additionally, lessons for each rule on the school’s expectations matrix would be developed and distributed. Giving teachers a direct instruction lesson that addresses non-classroom settings sets the expectation that teaching social skills will be a year long effort. Why is it Important to Teach Social Skills? Teaching social skills is one of the necessary essential features of the Schoolwide Positive Behavior Support process. The emphasis on teaching all students important expectations is based on two assumptions: 1) All behavior (both appropriate and inappropriate) is learned, 2) thus appropriate behavior can be taught using the same basic principles with which academic content is taught (Colvin, Sugai & Patching, 1993). Many students who struggle the most with social skills have not had an opportunity to learn the social skills expected in school. The most efficient approach is to teach social skills directly. What is Direct Instruction of Social Skills? Direct instruction of social skills is when teachers explain exactly what students are expected to learn, and demonstrate the steps needed to accomplish a particular social skill. Direct instruction takes learners through the steps of learning systematically, helping them see both the purpose and the result of each step. Direct instruction is the most efficient method of teaching the social skills. “To increase the likelihood of students using social skills appropriately across people, places and situations, teaching procedures should include multiple examples, practice within and across multiple settings, instruction on self-management skills, and involvement of a variety of people” (Lewis and Sugai, 1999, p. 6). Steps to Direct Instruction of Social Skills • Tell students lesson objectives • Tie to prior knowledge • Model, show examples • Role play positive examples • Students practice, practice, practice & are given performance feedback • Make connections with other curricular areas 3 • When errors occur, re-teach again and again Are There Ways to Indirectly Teach Social Skills? • After specific social skills have been directly taught, it is helpful to give students precorrects before they are asked to perform the skill. Precorrects function as reminders and can be particularly helpful when teachers anticipate students will have difficulty with the skill. A precorrect example: After students have been directly taught to listen to adult directions, teachers can say after giving an attention signal. “Before we begin, remember the steps to listening to adult directions are eyes on me, voice off and body to self.” • Often there are natural opportunities throughout the day to practice, practice, and practice social skills. Practice helps students • maintain previously learned knowledge • focus on current lessons • tie current content with previously learned content • generalize of skills taught in class to other non-classroom settings • Identify times and places when it is difficult to use social skills they have been taught What Roles Do Nonclassroom Staff Have to Support Social Skills Instruction? • All adults in the building should be fluent with the language of the school-wide expectations (e.g. safe, ready, respectful) and use them when interacting with students. • All adults in the building should model the behaviors we expect of the students. For example, if students are expected to use quiet, respectful voices in the hallway, all staff should use quiet, respectful voices in the hallways too. • All adults can support students who are using the social skills they have been taught by giving students specific and positive feedback. A sincere comment such as “Thanks for being responsible and moving onto class guys” helps support students’ use of social skills they have been taught. • Corrective interaction focus on reteaching the expected behavior as any learning error would be taught (Example: 1. What should you be doing? 2. Do you need help doing it? 3. Let me see you do the behavior!) How Will We Know if Adults are Teaching? • Adults model expected social skills (e.g., walk on the right, voices off in the hallways) • Teachers make student work visible—posters, stories, goals, data • Hear staff use expectations language regularly as they give students precorrects and performance feedback each day, all day, all year • The school environment is calm, organized, and positive References: Colvin, G., Sugai, G., & Patching, B., (1993). Precorrection: An instructional approach for managing predictable problem behaviors. Intervention in School and Clinic, 28, 143-150. 4 Lewis, T.J., & Sugai, G. (1999). Effective behavior support: A systems approach to proactive schoolwide management. Focus on Exceptional Children, 31(6), 1-17 Elementary PBS Lesson Plan Week of Implementation: Specific Skill: I Can Show Respect For Others Skill Steps/Learning Targets – This means I will: Keep hands, feet and objects to self Listen attentively to the designated speaker (see lesson “I Can Listen Attentively” for skill steps) Use appropriate volume and tone with my voice Use kind words and positive body language Context: All Settings TEACHING= Tell+ Show+ Practice+ Feedback+ Re-teach TELL (this should be a BRIEF opener to the lesson, the lesson emphasis should be on student guided practice) This component provides an introduction to what the skill is, rationale for why we need it, and a brief discussion of what are the skill steps. What is the skill? Choose one of the following to introduce the skill. State the skill: Today we are going to review the skill “I can show respect for others”. Quote: “I am not concerned with your liking me or disliking me…All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.” Jackie Robinson Data from school survey, SWIS, MSIP, etc. Read a piece of literature, picture book, social story, fiction, an excerpt from a novel or an article: 1. Shubert’s Helpful Day by Becky Bailey (K-3) When one of his classmates arrives at school upset and angry, Shubert and his friends help her to deal with her feelings in a positive manner. 2. Oliver Button Is a Sissy by Tomie dePaola (K-3) His classmates' taunts don't stop Oliver Button from doing what he likes best. 3. Seven Spools of Thread by Angela Shelf Medearis, (2-5) When they are given the seemingly impossible task of turning thread into gold, the seven Ashanti brothers put aside their differences, learn to get along, and embody principles of cooperation, respect, and kindness. Activity: Create a T-Chart with two headings Non-examples and Examples of Respect by characters in the above mentioned books. If there are no respectful examples, ask class what examples of giving respect you have seen. Rationale - why would a student need to know this skill? In what school settings would a student need this skill? Also make connections to life beyond school, i.e., the workplace, home, higher education, etc. Discussion: Showing respect is a lifelong skill. Just like the signs of respect we show at home, in the community and at jobs, signs of respect are necessary at school. Students show respect numerous times throughout the day at school. Sometimes students show respect to help them communicate well and get the things they want and need. Sometimes students show respect to keep them out of trouble. Are there other reasons for being respectful? Discuss Skill Steps –using the list of skill steps above, quickly review the behavioral expectation for appropriately showing respect to others. 5 Showing Respect means we: 1) keep hands, feet and objects to self, 2) listen attentively to the designated speaker, 3) use appropriate volume and tone with my voice, and 4) use kind words and positive body language. 6 SHOW Teacher Model: both examples and non-examples Example Keep hands, feet and objects to self Listen attentively to the designated speaker Use appropriate volume and tone with my voice Use kind words and positive body language Almost There Non-Example TEACHER ONLY TEACHER ONLY Sometimes touches others Students’ hands or feet are purposefully playing or hurting Student does not give with objects/others undivided attention Students are not listening, even Student responds after redirects correctly with words but without appropriate tone, Student raises voice and uses volume or body language rude tone Student argues, complains, blames others, uses inappropriate language, rolls eyes or walks away Student throws or uses objects inappropriately Scenarios Read or act out the scenarios below and have students identify whether the behaviors are examples, “almost there” or non-examples. Whenever possible teachers can/should make a connection to other curricular areas such as ties to a character from literature, current events, famous quotations, or to a content area. Non-examples The teacher is teaching the math lesson and Alex is busy cleaning out his binder. Students are lining up to come in from recess. Ralph and Kierra start bumping each other. Then they start pushing and shoving each other into other students in line. It takes ten minutes to get the class calmed down and into the building. Because of the incident, the class can not get a drink because it is time for art. Almost There examples: The class was leaving the assembly. While walking in the hall, the students were excitedly talking about the play. The teacher reminds the class that others are learning. “Voices are off in the hall, we can talk about the play when we get to class.” The class gets quiet and walks down the hall. Taurus is pestering Samantha by playing with the papers on her desk. Samantha asks him to stop and he doesn’t so she loudly tells him to stop and he does. Examples: Juan sits next to Joel at the cafeteria table. Joel moves his food and scoots closer to his buddy. Juan uses an “I message” When you move away from me, I feel mad and I’d like you to sit by me at lunch.” Joel apologizes and moves back to his spot. During Music class, the teacher calls on the first row to play the drums. The students in row 2 and 3 listen to the musicians and wait their turn because they know everyone always gets a turn. The teacher compliments the students by saying “Because you waited and listened to the first row play the drums, we will have enough time to sing your favorite song before we leave today.” 7 GUIDED PRACTICE Optimally practice would occur in the setting(s) in which the problem behaviors are displayed. The guided practice component of the lesson is a pivotal part of every lesson to ensure that students can accurately and appropriately demonstrate the skill steps (Lewis & Sugai, 1998). Where can ideas for role play/guided practice come from? During your introductory discussions your students may have shared specific examples or nonexamples and those would be excellent for use as role play situations and extension activities throughout the week. These examples can be written out on chart paper for later use. Pass out 3X5 index cards after the introduction of the skill and give students a moment to write down examples or non-examples they have experienced at school, home in the neighborhood, or at work. Young children can draw it! This option allows for anonymity. Save non-school examples primarily for discussion and use school based examples for role-play. In the case of non-examples, have students problem solve appropriate behaviors that could have been done/used instead and then have them role play these replacement examples. Students NEVER ROLE PLAY NON-EXAMPLES! If a non-example needs to be demonstrated it is ONLY demonstrated by TEACHERS/Adults. Give all students a task or job to do during ROLE PLAY! Some students will be actors; others can be given the task of looking for specific skill steps and giving feedback on whether the step was demonstrated. Sample role play scenarios: 1. Read the scenarios from Oliver Button is a Sissy where the older boys were playing catch with his shoes and the girls told the boys to leave Oliver’s shoes alone. Role play solutions that would show respect. 2. The teacher asks Sam to move to the safe seat because he is drumming on the desk with his pencil and dancing in his seat while the teacher is talking. Instead of getting up and going to the safe seat, Sam yells out, “Jacob was doing it, too. You aren’t sending him to the safe seat!” 3. The teacher asks Jonathan to move into the walk zone and he says, “Okay!” in a loud and angry tone. 4. The class has a substitute for the day. The substitute asks the class to line up for recess. Some students stand by their friends because they think the substitute doesn’t know their line order. Students argue loudly about their places instead of getting in line order. 5. Use your SWIS data to choose examples that your school or class can improve. FEEDBACK – Teachers can ensure that students have the opportunity to reflect on performance of social skills by providing frequent positive feedback that is both contingent and specific (re-stating of skill steps/ learning targets). Research clearly indicates that positive feedback of this nature increases future demonstrations of target social skills (Brophy, 1980). Following are some examples of phrases to use during practice sessions and throughout the rest of the year to give students performance feedback. “Thank you for showing respect for others by letting __________ sit next to you even though you wanted to sit beside your best friend.” “Great job keeping your eyes on the teacher and not getting distracted by the student throwing paper. I appreciate your respectful actions. ” “Thank you for showing respect to the substitute even though he or she did things differently than your teacher.” 8 “Thank you for showing respect to the teacher by moving to the end of the line without arguing or complaining.” What are some ways to get students to self-assess on their use of the social skill? o Assign “look fors” during role play. o Write or draw how they showed respect for others during the school day or during specials, recess, and cafeteria (depending on the area your students need to focus on). o Students report to teacher how they did in specials (do this with specialist or supervisor, then that person can affirm their self assessment) How can teachers tie the school-wide feedback system to this social skill? Can teachers use a whole class contingency, individual feedback or other system to quickly but SYSTEMATICALLY give ALL students contingent, positive and specific performance feedback? o Have charts for each period/hour where teacher or directed student can tally a “+” or “-“ for showing respect. o Use pre-made tangibles and hand to students displaying the skill and place in cans/tubs/bucket for specific period/hour. o Give school-wide tangibles to students, they sign and put in a random drawing box at the main office, or “cash-in” for various prizes or privileges at the designated time and place (if applicable to your school). RE-TEACH Review and Practice Throughout the Week Teacher can observe students for examples, almost there’s and non examples of showing respect for others throughout the week. Teacher can hold follow up discussion/have students categorize examples. Prior to beginning a lesson, teacher can review “listen attentively” behaviors Create a system for tracking respectful behaviors Example Almost There Non-example Do Instead Additional Activities: Teachers will have the opportunity to assess student knowledge and in some cases use of the social skills steps for learning primarily through role play and demonstration (performance) or during discussions (personal communications). In some circumstances the teacher may opt to assess student knowledge and perception of personal use of the social skills through the use of written work (extended response) or in limited fashion through the use of quizzes (selected response). Ideas for possible curricular/content or extension activities are provided below. Reference: Columbia Public Schools, Positive Behavior Support: www.columbia.k12.mo.us/staffdev/cpspbs/teach.htm 9 Middle School PBS Lesson Plan Week of Implementation: Specific Skill: I Can Show Respect for Others Skill Steps/Learning Targets – This means I will: Keep hands, feet and objects to self Listen attentively to the designated speaker Use appropriate volume and tone with my voice Use kind words and positive body language Context: All Settings TEACHING= Tell+ Show+ Practice+ Feedback+ Re-teach TELL (this should be a BRIEF opener to the lesson, the lesson emphasis should be on student guided practice) This component provides an introduction to what the skill is, rationale for why we need it, and a brief discussion of what are the skill steps. Choose 1 of the following to introduce the skill. What is the skill? State the skill: Today we are going to review the skill “I can show respect for others.” Quote: “I'm not concerned with your liking or disliking me... All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.” Jackie Robinson Data from school survey, SWIS, MSIP, etc. PBS Team to pull school data on disrespect (SWIS, MSIP, PBS Implementation Survey) Read a piece of fiction, an excerpt from a novel or an article: Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak: Max’s disrespectful behavior gets him sent to his room without any supper. Read beginning pages and ask students to name the disrespectful behaviors Max shows. Ask students to name others books where characters have displayed disrespectful behaviors. What were the outcomes of the characters’ behaviors? What might have the characters done differently? Activity: Cultural examples of respect (standing when a woman leaves/arrives at table, holding doors open for those behind you, removing a hat when you enter the building, standing for the national anthem). We have all seen examples of giving respect in our culture. What examples of giving respect have you seen? Why do people show these signs of respect? Rationale - why would a student need to know this skill? In what school settings would a student need this skill? Also make connections to life beyond school, i.e., the workplace, home, higher education, etc. Discussion: Showing respect is a lifelong skill. Just like the signs of respect we show at home, in the community and at jobs, signs of respect are necessary at school. Students show respect numerous times throughout the day at school. Sometimes students show respect to help them communicate well and get the things they want and need. Sometimes students show respect to keep themselves out of trouble. Discuss Skill Steps –Showing respect for others at school means: Keep hands, feet and objects to self Listen attentively to the designated speaker Use appropriate volume and tone with my voice Use kind words and positive body language 10 SHOW Teacher Model: both examples and non-examples Example Almost There TEACHER ONLY Non-Example TEACHER ONLY Keep hands, feet and objects to self Listen attentively to the designated speaker Use appropriate volume and tone with my voice Use kind words and positive body language Inconsistently keeps hands, feet and objects to self (may be able to recite expectations but not demonstrate them; may try to “get away with” doing non-example behaviors) Student does not give speaker undivided attention (may be listening, but doing other tasks on the side) Student responds correctly with words but not with tone or volume (says “Fine” in response to a request, but in a loud, rude tone or while walking away) Students’ hands or feet are busy playing with objects/others Students are not listening (sleeping, talking to others, working on other assignments/writing notes, not making eye contact with the speaker) Student raises voice and uses rude tone Student argues, complains, blames others, uses inappropriate language, rolls eyes or walks away Scenarios Read or act out the scenarios below and have students identify whether the behaviors are examples, “almost there” or non-examples. Whenever possible teachers can/should make a connection to their curricular area such as ties to a character from literature, current events (when appropriate), famous quotations, or to a content area (e.g., safety in industrial technology or science lab, plagiarism in any academic content area, etc.). Scenarios: 1. The teacher is teaching the math lesson and Alex is busy cleaning out his binder. 2. The teacher is giving directions for the book report due the next week, and Sandy is facing the teacher with her hands and feet to herself, writing down notes from the teacher’s directions. 3. The teacher asks Jonathan to move into the walk zone and he says, “Okay!” in a loud and angry tone. 4. Amanda chooses to sit near her best friend, Katie during the assembly. She wants to ask Katie if John asked her out, even though she knows she should be giving the speaker her undivided attention. 5. The teacher asks Sam to move to the safe seat because he is drumming on the desk with his pencil and dancing in his seat while the teacher is talking. Instead of getting up and going to the safe seat, Sam yells out, “Jacob was doing it, too. You aren’t sending him to the safe seat!” 6. The cafeteria supervisor asks for students to begin cleaning up and getting ready for dismissal from the cafeteria. Aaron stops talking, gathers his trash and wipes the table where 11 he is sitting. He turns to face the cafeteria supervisor and waits for further instructions. 12 GUIDED PRACTICE Optimally practice would occur in the setting(s) in which the problem behaviors are displayed. The guided practice component of the lesson is a pivotal part of every lesson to ensure that students can accurately and appropriately demonstrate the skill steps (Lewis & Sugai, 1998). Where can ideas for role play /guided practice come from? During your introductory discussions your students may have shared specific examples or nonexamples and those would be excellent for use as role play situations and extension activities throughout the week. These examples can be written out on chart paper for later use. Pass out 3X5 index cards after the introduction of the skill and give students a moment to write down examples or non-examples they have experienced at school, home in the neighborhood, or at work. This option allows for anonymity. Save non-school examples primarily for discussion and use school based examples for role-play. In the case of non-examples, have students problem solve appropriate behaviors that could have been done/used instead and then have them role play these replacement examples. Students NEVER ROLE PLAY NON-EXAMPLES! If a non-example needs to be demonstrated it is ONLY demonstrated by TEACHERS/Adults. Give all students a task or job to do during ROLE PLAY! Some students will be actors, others can be given the task of looking for specific skill steps and giving feedback on whether the step was demonstrated. Sample role play scenarios: o Students are exiting the building at dismissal. Have students role play how they SHOULD show respect for others. o Students are shoving in the line. An adult asks a group of students, one of whom wasn’t shoving, to go to the end of the line. Have students role play how they SHOULD show respect for others. o The substitute teacher asks a student to move to the safe seat. The student is not moving fast enough for the teacher so she yells “Didn’t you hear me?! You need to get up right now or I’m writing you up!” Have students role play how they SHOULD show respect for others, even if the adult is not showing respect. o A student is throwing paper at another while the teacher is reviewing the test. Have students role play to show how they SHOULD show respect for others, even if another student is attempting to distract them. FEEDBACK – Teachers can ensure that students have the opportunity to reflect on performance of social skills by providing frequent positive feedback that is both contingent and specific (re-stating of skill steps/ learning targets). Research clearly indicates that positive feedback of this nature increases future demonstrations of target social skills (Brophy, 1980). Following are some examples of phrases to use during practice sessions and throughout the rest of the year to give students performance feedback: “Thank you for showing respect for others by letting __________ sit next to you even though you wanted to sit beside your best friend.” “Great job keeping your eyes on the teacher and not getting distracted by the student throwing paper.” “Thank you for showing respect to the substitute even though you did not feel respected by her.” “Thank you for showing respect to the teacher by moving to the end of the line without arguing or complaining.” Here are some ways to get students to self-assess on their use of the social skill: o Assign “look fors” during role play. o Give students self-monitoring sheets with skill steps. o Write down examples of how you showed respect for others during a school day. Below are ideas for teachers to tie the school-wide feedback system to this social skill: o Have charts for each period/hour and hold a friendly competition where teacher or directed student can tally. o Use pre-made “admit one” tickets and hand to students displaying the skill, place in cans/tubs/bucket for specific period/hour and have random weekly drawings. o Give school-wide tickets to students, they sign and put in a random drawing box at the main office, or “cash-in” for various prizes or privileges at the designated time and place. RE-TEACH Review and Practice Throughout the Week Following are examples of how teachers can re-visit this social skill throughout the week and in the coming months of the school year. Teacher can observe students for examples, almost there’s and non examples of showing respect for others throughout the week. Teacher can hold follow up discussion/have students categorize examples. Prior to beginning a lesson, teacher can review “showing respect for others” behaviors Create a system for tracking respectful behaviors Example Almost There Non-example Do Instead Have students fill out cards like this one and drop it in a box When the chart (10 rows) is completely filled with examples then class celebrates Description of Behavior: ____________________________________ ____________________________________ ____________________________________ Person Observing: _____________________ 14 Additional Activities: Ideas for possible curricular/content or extension activities are provided below. FISHBOWL In this activity 3-5 kids (FISH) are coached on displaying a set of behaviors. These students perform a scenario in front of the entire class in a “fishbowl.” The students in the class watch the fish in the fishbowl, taking notes on their behaviors that show respect for others. Behaviors are discussed after 1-2 minutes of acting. A variation is that students in the class can volunteer to “replace” fish in the fishbowl if students think they can display behaviors more effectively. Students in class Students in class fish Students in class Curricular or Content Connections In content classes when students are asked to work in cooperative groups, teacher can begin class with the Jackie Robinson quote (“I'm not concerned with your liking or disliking me... All I ask is that you respect me as a human being.” Jackie Robinson) on the overhead and ask students to explain how this quote applies to working in groups. Reference: Columbia Public Schools, Positive Behavior Support: www.columbia.k12.mo.us/staffdev/cpspbs/teach.htm 15 High School PBS Activities Are You a Respectful Person? (Take this self-evaluation and decide for yourself.) True False I treat other people the way I want to be treated. I am considerate of other people. I treat people with civility, courtesy, and dignity. I accept personal differences. I work to solve problems without violence. I never intentionally ridicule, embarrass, or hurt others. I think I am/am not a respectful person because: ___________________ WRITING ASSIGNMENTS 1. How does government "of, by, and for the people" depend on respect? Write an essay connecting the concepts of democracy and respect. How is listening to different points of view a sign of respect and a cornerstone of democracy? What is it about the concept of democracy that relies upon mutual respect among people? How is the very concept of democracy related to respect for the individual? 2. Watch a sitcom on television, and then write about how the actions of the characters demonstrated either respectful or disrespectful behavior. 3. Bullies are often trying to make people "respect" them. Is this really respect, or is it fear? What is the difference? How is bullying and violent behavior an act of disrespect? 4. Write about a time when you were disrespectful to someone. Why did it happen? Was it the right thing to do? What were the consequences? How did it make the other person feel? What did you learn from the experience? 5. Describe three things you could do to be a more respectful person. How would that affect your relationships with others? How does it benefit you to be a respectful person? 6. In the video one teen talks about a ripple effect: If one person treats another with respect, the respect begins to spread out from there. Write an editorial for your school newspaper encouraging students to start the "respect ripple effect." Describe what it could accomplish in your school setting. 16 STUDENT ACTIVITIES 1. Conduct a survey in your school or community, asking questions like these. Do you think people are respectful enough? What are some disrespectful acts that really annoy you? What are some respectful acts that you especially appreciate? Compile the results into a report. 2. Brainstorm ways to make your school environment more respectful. Create a list of recommendations and place them in your school newspaper or on a poster. 3. Divide the class into small groups. Have each group develop a list of do’s and don’ts for being a respectful person. Have them make oral reports to the class addressing the following questions: What happens when people live in accordance with these guidelines. What happens when they don’t. In what ways does respectful and disrespectful behavior affect our community and society? 4. Bring in articles from newspapers and magazines describing situations in which respect or disrespect are issues. Talk about who is acting respectfully, and who is acting disrespectfully in these situations. Using the articles as evidence, tell the class about the consequences of disrespectful and respectful behaviors. 5. Role play some typical situations in which disrespectful behavior leads to hostility and maybe even violence. Then, change one of the disrespectful actions into one of respect and see how the outcome changes. Copyright Elkind+Sweet Communications / Live Wire Media. Reprinted by permission. Copied from www.GoodCharacter.com. 17 Resources & References Literature-based resources: Bambara, L.M., Dunlap, G., & Schwartz, I.S. (2004). Positive behavior support: Critical articles on improving practice for individuals with severe disabilities. TASH, ProEd. Bambara, L.M., & Kern, L. (2005). Individualized supports for students with problem behaviors: Designing positive behavior support plans. New York: Guilford Press. Bambara, L., & Knoster, T. (1998). Designing positive behavior support plans. Innovations (no. 13). Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation. Blair, K., Umbreit, J., & Bos, C. (1999). Using functional assessment and children's preferences to improve the behavior of young children with behavioral disorders. Behavioral Disorders, 24(2), 151-166. Carr, E.G. (2007). The Expanding Vision of Positive Behavior Support: Research Perspectives on Happiness, Helpfulness, Hopefulness. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(1), 3-14. Carr, E.G., Horner, R.H., Turnbull, A.P., Marquis, J.G., Magito McLaughlin, D.McAtee, M.L., Smith, C.E., Anderson Ryan, K., Ruef, M.B., & Doolabh, A. (1999). Positive behavior support for people with developmental disabilities: Research synthesis (American Association on Mental Retardation Monograph Series). Washington, D.C.: American Association on Mental Retardation. Ellingson, S.A., Miltenberger, R.G., Stricker, J., Galensky, T.L., & Garlinghouse, M. (2000). Functional assessment and intervention for challenging behaviors in the classroom by general classroom teachers. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 2, 85-97. Foster-Johnson, L., & Dunlap, G. (1993). Using functional assessment to develop effective, individualized interventions for challenging behaviors. Teaching Exceptional Children, 25, 44-50. Freeman, R.L., Baker, D., Horner, R.H., Smith, C., Britten, J., & McCart, A. (2002). Using functional assessment and systems-level assessment to build effective behavioral support plans. In K.C. Lakin & N. Wieisler (Eds.), Alternative community behavioral support and crisis response programs (pp.199-224). [Monograph]. American Association on Mental Retardation. Janney, R., & Snell, M.E. (2000). Teacher’s guides to inclusive practices: Behavioral support. Baltimore: Brookes. 18 Jolivette, K., Lassman, K. A., & Wehby, J. H. (1998). Functional assessment for academic instruction for a student with emotional and behavioral disorders: A case study. Preventing School Failure, 43(1), 19-23. Koegel, L.K., Koegel, R.L., & Dunlap, G. (1996). Positive behavioral support: Including people with difficult behavior in the community. Baltimore, MD: Brookes. Lee, Y., Sugai, G., & Horner, R.H. (1999). Using an instructional intervention to reduce problem and off-task behaviors. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 1(4), 195204. McIntosh, K., Horner, R.H., Chard, D.J., Boland, J.B., & Good, R.H. (2006). The use of reading and behavior screening measures to predict non-response to school-wide positive behavior support: A longitudinal analysis. School Psychology Review, 35, 275-291. O'Neill, R.E., Horner, R.H., Albin, R.W., Sprague, J.R., Storey, K., & Newton, J.S. (1997). Functional assessment and program development for problem behavior: A practical handbook (2nd ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Repp, A.C., & Horner, R.H. (Eds.). (1999). Functional analysis of problem behavior: From effective assessment to effective support. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Co. Taylor, J.C., & Carr, E.G. (1992a). Severe problem behaviors related to social interaction. I: Attention seeking and social avoidance. Behavior Modification, 16, 305335. Wehmeyer, M.L., Baker, D., Blumberg, R., & Harrison, R. (2004). Self-determination and student involvement in functional assessment: Innovative practices. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 6, 29-35. Web-based resources: Association for Positive Behavior Support: www.apbs.org Columbia Public Schools, Positive Behavior Support: www.columbia.k12.mo.us/staffdev/cpspbs/teach.htm Oregon Department of Education: http://www.ode.state.or.us/initiatives/idea/pbs.aspx Tary Tobin (University of Oregon’s College of Education): http://www.uoregon.edu/~ttobin/ Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention: http://www.challengingbehavior.org/explore/pbs/pbs.htm 19 National Technical Assistance Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs): www.pbis.org Medline Plus (A service of the U.S. National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health): http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/childbehaviordisorders.html University of Florida: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/HE136 20