Materials for English Literature - Il Liceo “G. Cesare

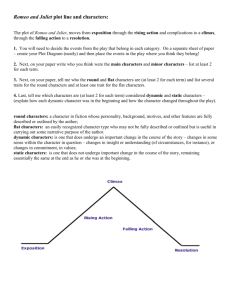

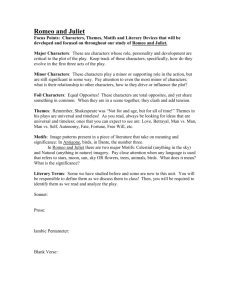

advertisement