Maritime Trades: Sail Making, Its Influence in Empowering the Free

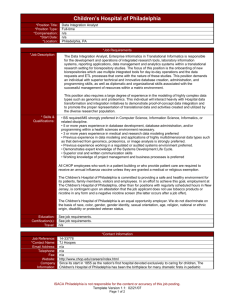

advertisement

Maritime Trades: Sail Making, Its Influence in Empowering the Free Black Community in Post Revolutionary War Philadelphia In the newly coalesced nation called the United States of America, the black experienced at sea is usually a painful reference to the horrors of the middle passage during the transatlantic slave trade. Yet in the wharves, and docks of the eastern seaboard of the newly formed country, black maritime laborers, free and enslaved were the normality instead of the exception. Philadelphia had one of the most viable ports and shipping docks in the nation because of its mid-Atlantic position interconnection the commodities from Southern and Caribbean plantations to the New England mills, factories and other industries. At least 20% of shipwrights in Philadelphia during the late 18th century until the early portion of the 19th century were black men. Caulkers, pilots, and sail makers consisted of skilled and semiskilled black mariners who worked in Philadelphia which was one of the larger colonial tonnage producers. The Southern plantation system in the former colonies was an economic stimulus for commercial growth along urban areas of the Atlantic, both in America and Europe. Plantation commodities such as sugar, tobacco, coffee and rum were exported to European markets from Philadelphia. Plantation owners, merchants, bankers and slave traders were dependent on maritime transport. The plantation system was a blend of elements from European feudalism and capitalism. It brought about the privatization of land with entrepreneurs and merchants that accumulated profit and capital. In the northern region of the United States, the plantation system was impractical and the need for large populations of slave labor gradually, but not totally, diminished in Philadelphia when the colonies strived to recovered from the economic slump after the Seven Years War. The growing free black community had few opportunities in a predominately agrarian society. Productive land was extremely difficult to obtain for free blacks, as well as, training and employment in trades. Maritime work was the mainstay for the free black community in Philadelphia until the latter half of the 19th century. In the backdrop of a competitive power and profit driven plantation economy, maritime trades offered financial sustainability for free blacks in a capitalist economy ensnared by profits from slavery. With its lively seaboard history, it was not a coincidence that Philadelphia was the birthplace of the most influential and wealthiest sail maker, black or white, James Forten. The assembly of a sail was a signature craft that served as a testimony to the training, dexterity and reputation of its maker. Each ship’s sails were custom made portions of canvas arranged carefully on loft floors inside large warehouses near Philadelphia docks. A well made sail was an essential component for the survival of the ship’s crew and its cargo. Young boys, striving to earn an apprenticeship with a master sail maker, were employed to keep the loft floor immaculate to prevent the sail canvas from becoming damaged. Most of the fabric scraps were retrieved to become patches for ships that docked in Philadelphia’s harbors. Wax chips were remelted and cut into small blocks for the apprentices and journeymen that used the wax to water proof sail stitching. If a young man like James Forten, proved themselves, he would obtain an apprenticeship from a master sail maker such as Thomas Bridges. The young apprentice was required to learn the anatomy and physiology of the sail. He also had to prove his proficiency with the nomenclature and use of the specialized implements of the trade. Apprentices, such as Forten, were required to carefully polish, clean and sharpen their tools which were kept stored in special cases constructed of leather or wood. To advance to journeymen, the apprentice was expected to master the numerous types of stitches, and evaluate the quality of the canvas fabric. Canvas of poor grade and quality would not be able to withstand the shear stresses of ocean winds and corrosive effects of a saltwater environment; therefore the sail maker used a fid to determine how easily the fabric separated. As journeymen, James Forten and others, had to draft and make precise measurements for each sail’s riggings. James Forten honed his skills for sail making under the instruction of his father’s employer, Thomas Bridges. Forten, born in 1766, was the son of free parents Thomas and Margaret. He was educated in Quakers schools until the death of his father at the age of seven. Prior to the apprenticeship in Thomas Bridges’ loft, Forten signed up as a privateer to generate income for his family during the Revolutionary War as did many shipyard workers. Forten’s brief school education and knowledge from sailing gave him an additional advantage and understanding of the necessary calculations that were needed to pattern the canvas for riggings, cut the panels, and mark how each piece had to be sewn together. Forten’s acumen and caliber of character helped him to obtain the position as foreman of Thomas Bridges’ loft. When Bridges retired, Forten purchased the business. His sail making loft became well known for its success and for the harmony and peace established in a workplace of employees of varied hues and nationalities. James Forten invented a device for sail handling although he did not receive a patent for it. He also experimented with various sail types and designed a sail that was suitable for greater speed and maneuverability. The financial independence of Philadelphia’s most prominent and wealthiest sail maker did not cloud Forten’s awareness of the plight of over two million enslaved brethren and the impoverished free blacks of the city. In America, the free black community had a precarious status as tolerated non-citizens in the northern states and as pestilence to southern plantation owners. Philadelphia had one of the largest free black communities in the young nation. Many enslaved blacks obtained their freedom from the Gradual Abolition Act of 1780 which legally freed any slave brought into Philadelphia after March 1, 1780 that resided in the city for six months. The slowing economy caused by loss of demand for American farm products, the closing of British East Indies ports to American merchants and an influx of unemployed veterans, spurred the manumission of many blacks in surrounding rural areas in Pennsylvania. The surge of blacks moving into the state alarmed white citizenry and caused the Pennsylvania Senate to draft a bill that restricted black immigration by requiring the immigrants to register. Forten raised black awareness about the bill in his pamphlet, “A Series of Letters by a Man of Color”. He felt the bill reinforced the view of black inferiority and was successful in getting the free black community to sign petitions and get the bill dropped. Forten and other free blacks in the maritime societies and abolitionist societies obtained petitions to amend the gradual abolition act to include the outfitting of slave ships in Philadelphia shipyards as illegal. The amendment also prohibited the transport of enslaved pregnant women and children to slave states. During the War of 1812, James Forten led the Black Committee of Defense, which mobilized over 1,500 black men to protect Philadelphia from British attack. After the war, another economic depression impacted America and lasted from 1816 to 1823, coupled with the yellow fever epidemic. Philadelphia’s black community grew from an influx of black escaping from the lower Southern states and from the West Indies. With waves of poor white immigrants moving to the city, there was growing racial antipathy as jobs became scarce. Caricatures demonizing Philadelphia’s black community as immoral savages along with proponents of black inferiority theorists such as Trench Coxe, flourished. Although the black community worked together with whites to defend the city, several blacks were attacked and black churches were burned by race riots during the early decades of the 1800’s. James Forten with Richard Allen and other prominent black leaders organized the Convention of Color in 1817. Many black leaders were considering the establishment of a colony in Liberia spurred by the American Colonization Society (ACS). With the growing white antipathy, many black leaders felt it was futile trying to build a future as a free black citizen in the United States. The colonization effort seemed appealing because it had the support of white societies that supported abolitionist causes. James Forten, Absalom Jones and Gloucester held a meeting with over 3,000 members of the black community to gain support from the black masses to colonize Liberia. Black leaders such as Forten were shocked when the masses rejected the colonization effort; the leadership later discovered the ACS was supported by southern politicians and plantation owners. Forten and other Philadelphia black leaders used their influence to protest the ACS as a deportation scheme that was trying to rid the country of free blacks to continue slavery. After the War of 1812, the demand for slaves in the south increased. The free black communities in Philadelphia and other northern cities were threatened by a rise in the kidnapping of free blacks to be sold into slavery. Forten and the free black communities across the nation pushed to strengthen penalties for convicted kidnappers. Forten and other black maritime workers understood their status in the black community as role models. They established temperance societies that shunned gambling and drinking to remove the stigma of immorality associated with shipwrights. They sacrificed additional income by refusing to service slave vessels. Even though there was a public education law passed in 1818, Philadelphia black leaders instinctively felt the system was not prepared to include black children. James Forten and others founded the Augustine Society of Pennsylvania for the education of children of color. Benevolence societies were started to help the impoverished blacks who were denied assistance from almshouses because of their skin color. In the Anti-Slavery Record, James Forten, the sail maker, was described as “A Noble Example”. He spoke for the voiceless two million enslaved blacks by helping empower the free community. The egalitarian atmosphere that he established in his loft, he worked tirelessly to have established in the country that did not want him but he still considered it his. Bibliography Primary: Black Hands, Blue Seas: Letters of Paul Cuffe. Exhibit at Independence Seaport Museum, Philadelphia, PA, March 2009. Forten, James, “Letters to Cuffe,” Africans in America, PBS, 1998. The Anti-Slavery Record: “A Noble Example”, December 1835, www.nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds Secondary: Bolster W. Jeffrey, Black Jacks: African American Seamen in the Age of Sail, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard, 1998). Nash, B. Gary, Forging Freedom: The Formation of the Philadelphia Black Community, 1720-1840, (Harvard University Press, 2004). Nesbit, Joanne, A Privileged Environment, No Protection from Racism, (The University Record, 13, Feb. 1996). Winch, Julie, Gentleman of Color: The Life of James Forten, (New York, NY: Oxford, 2002).