class notes for chapters 1-3

advertisement

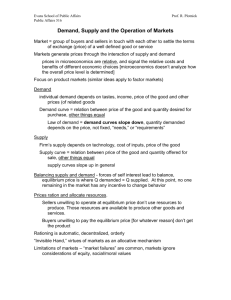

1 Class Notes Chapter 1: Introduction to Economics Definition (Parkin&Begg): Economics is the social science that studies the choices of individuals, businesses, governments about 1- what goods and services to produce, 2- how to produce these goods and services, 3- for whom to produce these goods and services. What to produce? Goods: steel, computers, cars, houses, etc. Services: insurance, hotels, transportation, education, retail and wholesale trade, etc. How to produce? Factors of production: Land, Labor, Capital, Entrepreneurship. Land is natural resources, raw materials, water, air. Labor is the time and effort given by workers. Capital is the machinery, equipment and buildings used during production. For whom to produce? Who will be able to buy goods and services? This depends on consumers’ income and budget constraint. 1.1 Scarcity: Human beings have unlimited wants. We want the best cars, cell phones, houses, education, vacations, etc. But we cannot obtain all of our wants because our resources are limited. We need money and time to buy and enjoy these goods and services (from consumer’s perspective). So our resources are scarce. Economics considers how prices and markets allocate scarce resources to unlimited wants of the society. Example1: Turkish society and government wants to put a computer in every classroom in primary schools. The government also wants to build a nuclear power 2 plant. This will reduce Turkey’s energy bill of 25 billion USD every year for natural gas and oil to other countries. But the government does not have enough money to realize both objectives (Govt. has a budget). Government has to choose between: 1- putting a computer in every classroom in the country 2- building a nuclear power plant. The fact that government has to choose where to spend its money is called a tradeoff. Like government, all firms and individuals always face tradeoffs. They have to allocate their scarce resources to their most efficient use. Example2: every consumer has a certain income and has to do a budget. As a consumer, you cannot buy everything you want. For example, if your monthly income is 1000 liras, and you have to pay 700 liras for rent and other bills, then you have 300 liras to decide what to buy. Let us say a nice cell phone is 300 liras and a textbook is 50 liras. Then you have to choose between the textbook and the cell phone. This is a tradeoff. Here, the opportunity cost of one cell phone is equal to 6 textbooks. 1.2 Opportunity Cost Definition: (Parkin) The opportunity cost of an action is the value of the next-best alternative action. When there are only two goods as in the example of cell phone and textbook, Opp. Cost is easy to calculate. Example1: Let us say I have 1 TL in my pocket. I want to drink a cup of tea and eat 1 cookie. A cup of tea is 0.65 TL and 1 cookie is 1 TL. Can I buy both the tea and the cookie with my 1 TL? No I can only buy either the tea or the cookie. The opportunity cost of one cookie is the amount of tea that I have to “forego”, i.e. not buy. 1 cookie is 1 TL, which buys 1 / 0.65 (=1.54) cups of tea. So, opp. Cost of 1 cookie is 1/ 0.65 cups of tea. 3 Example2: On Sunday morning, I have three choices: sleep, go jogging or have breakfast with friends. Assume that my best choice is to sleep, then to go jogging and last choice is to have breakfast. Then the opp. Cost of sleeping is to go jogging. Opp. Cost of jogging is to have breakfast. To illustrate Opp. Cost concept, let us introduce the Production possibilities frontier. 1.3 Production Possibilities Frontier Like a consumer cannot consume everything she wants, an economy cannot produce an infinite amount of goods and services. Because the resources of an economy like Labor, Land and Capital are fixed (scarce) at any given time. Economists like to use models to illustrate ideas, so we use PPF to illustrate scarcity and tradeoff. FIGURE 1 (Parkin): Production Possibilities Frontier shows the boundary between what an economy can produce and what it cannot produce. CDs (millions) A 15 55 512 B C G unattainable D 9 Z E 5 attainable 1 2 F 3 4 5 pizzas (millions) 4 POSSIBILITY: A B C D E F TABLE 1 PIZZAS (MILLIONS) 0 1 2 3 4 5 CDS(MILLIONS) 15 14 12 9 5 0 Idea: As we want to produce more pizzas, we must produce less CDs, because our resources are limited (fixed). Attainable points are the points inside and on the curve. They show points that this economy can produce. Unattainable points are points beyond the PPF curve and these points cannot be produced. Points on the curve are called efficient. This means all of the resources are spent on production. At a point such as Z, some of the resources are not used efficiently, so we call such points inefficient. At point Z, we can produce both more pizzas and more CDs. İf we are on point D and we want to increase CD production, the only way is to decrease pizza production. So point D is efficient and Z is not. Opportunity cost: At point C, we produce 2 pizzas and 12 CDs. İf we want to increase pizza production from 2 to 3, we cannot do this without decreasing CD production from 12 to 9. This is because a point such as G is impossible to produce. Then the opportunity cost of 1 pizza is 3 CDs. One pizza costs us 3 CDs. To get 1 pizza, we give up 3 CDs. We come to point D. We can also calculate the opportunity cost of one CD in terms of pizzas. At point D, increasing CDs by 3 costs us 1 pizza. So opportunity cost of 1 CD is 1/3 pizza (3CD=1pizza, 1CD=1/3pizza). Increasing opportunity cost: Opp Cost of 1 pizza is not constant. From point D, if we want to increase pizzas again by 1, then we have to give up 4 CDs and come to point E. Then the opportunity cost of 1 pizza becomes 4 CDs. Notice that opportunity 5 cost of 1 pizza increases as we produce more and more pizzas. Opportunity cost increases because as we want to produce more pizzas, we force the resources that are more specialized for CD production to pizza production. For example, workers at SONY can produce many CDs easily because they are experienced in CD production. If we move them to pizza production, they are not specialized in pizza production so they will make a small amount of pizza. We get a small increase in pizza production but a large decrease in CD production. Does the PPF ever shift? Can the economy produce more of each good? Economic growth takes place when the PPF shifts outward. This happens due to an increase in factors of production (Land, labor, capital) or new developments in technology. If factors of production and technology are constant, PPF is constant. 1.4 Role of markets and prices in resource allocation: Markets are very useful in allocating resources efficiently in an economy. Prices signal and influence the behavior of sellers and buyers in a market. It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their self interest. —Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (1776) In a Free- Market Economy, buyers and sellers follow their own self interest. Surprisingly, the resulting outcome is usually an efficient outcome. By following their own self-interest, buyers and sellers help the economy become efficient. For example, if people start to like pizzas more instead of lahmacun, then price of pizzas would increase, a lot of lahmacun restaurants will switch to pizza production. Pizza production increases because both consumers want to buy more pizza and producers want to sell more pizza. Prices are a very important signal in this process. To see how free markets are good for the economy; we can look at the Centrally Planned Economies in the former Soviet Union, North Korea or Cuba. In a centrally planned economy, everything (land, factories, restaurants) is owned by the government and government has to decide what to produce and how much to produce each good and who will be able to buy the goods that are produced. This 6 planning is very complicated when you think of millions of goods and services to be produced. If people start to like pizzas more in a centrally planned economy, then they have to write letters to the government and ask for more pizza restaurants in their town. It would be a very inefficient system. Prices do not signal and influence buyer and seller behavior in a centrally planned economy. In a free market economy, prices are very important signals that determine behavior of buyers and sellers. What about the last global financial crisis that hit US, Europe and Japan? What we are learning from this crisis is markets should not be completely free from government intervention. Rules and regulations imposed by the government in the financial sector and the other sectors are necessary. 1.5 Microeconomics and macroeconomics Economics has two broad branches: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Microeconomics studies the economic decisions of an individual, firm or groups of firms and individuals. Also, microeconomic problems are specific to an industry (=sector) or a commodity. For example, microeconomic questions include: 1- Why are people buying more DVDs and less movie tickets? 2- How would a tax on internet shopping affect e-Bay? 3- What are the effects of a strike in Turkish Airlines on tourism industry? 4- What is the effect of the strong lira on textile industry? Macroeconomics studies the economy as a whole. Macro does not consider an individual or firm or industry (sektör). Macroeconomics studies the Turkish Economy or another country’s economy, or the global economy. Macro questions include: 1- Gross Domestic Product: This is the total value of all goods and services produced in a country in a year. GDP per capita shows the average income of a person in a country. 7 2- Consumer Price Index: Average price of all goods and services that a consumer buys. Inflation is the rate of change (increase) of CPI. 3- Can the Central Bank of Turkey make everyone richer by printing money and dropping from helicopters? 8 Chapter 2: Basics of Supply and Demand 2.1 Market A market is an arrangement where buyers and sellers of a good or service meet. Sometimes this is a place, like a vegetable-fruit Bazaar or the supermarket. Sometimes buyers meet sellers on the telephone or the internet. We categorize markets according to the good, for example “market for milk” or “market for tobacco” or “market for stock exchange IMKB”. Markets can be defined narrow or wide: market for milk versus market for food. 2.2 Demand Demand is the total quantity of a good that buyers want to buy at every price during a given time period. Demand explains behavior of buyers-consumers in a market. On this TABLE 2, the demand for a chocolate bar is given. TABLE 2 Point A B C D E Price Quantity Demanded (liras per bar) (millions of bars per week) 0.5 22 1.0 15 1.5 10 2.0 7 2.5 5 The law of demand: From Table 2, we can see that as the price goes up, buyers want to buy less. This is the law of demand: Other things constant, the higher the price of a good, the smaller is the quantity demanded; and the lower the price of a good, the greater is the quantity demanded. Demand curve is the graphical representation of a demand relationship between price and quantity demanded. 9 price (liras/bar) 3.0 E 2.5 D 2.0 C 1.5 B 1.0 demand for energy bars A 0.5 5 10 15 20 25 quantity demanded (million bars) FIGURE 2 “Demand” versus “quantity demanded”: The term demand refers to the entire relationship between the price of a good and the quantity demanded at every price. Demand is represented as a demand curve. The quantity demanded of a good is the quantity that consumers want to buy at a particular price. Quantity demanded is a point on the demand curve. Change in demand: If some other factor other than price changes the demand behavior of consumers for a good, then the demand curve shifts. When demand curve shifts, this means that quantity demanded changes at every price. Figure 3 and Table 3 illustrate an increase in demand for chocolate. Here, qty of chocolate demanded increases by 10 bars at every price. Point Price (liras per bar) A B C D E 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Quantity Demanded (millions of bars per week) 22 15 10 7 5 Point Quantity demanded A’ B’ C’ D’ E’ 32 25 20 17 15 10 Table 3 : An Increase in Demand FIGURE3: An Increase in Demand (demand curve shifts to right) price (liras/bar) 3.0 E E’ 2.5 D 2.0 D’ C’ C 1.5 B’ B 1.0 A’ A 0.5 5 10 15 20 25 32 quantity demanded (million bars) Movement along the demand curve: If all other factors are constant and only price of the good changes, then we move along the original demand curve. For example, starting with the original demand, if the price of chocolate increases from 1 lira to 2 liras, then quantity demanded decreases from 15 to 7. In this case demand curve does not shift because the change is a price change. Factors that change demand (and shift the demand curve): The following nonprice factors cause demand curve to shift. If price of the good changes, demand curve does not shift, we move along the curve. 1- Prices of related goods: Consider the market for (gas) benzene. If the price of LPG decreases, all other things constant, what happens to demand for benzene? Demand for benzene decreases because people will buy cars that operate with LPG instead of benzene. LPG and benzene are thus substitute goods. A substitute is a good that can be used in place of another good (Ex: a Toyota and a Honda, Tea and Coffee). 11 If the prices of cars decrease, what happens to demand for benzene? Demand for benzene increases because benzene and cars are complement goods. A complement is a good that is used together with another good (Ex: tea and sugar). 2- Income: Usually when income increases, demand for most goods increases. These are called Normal goods like cars, washing machines, etc. If the demand for a good increases when incomes rise, this good is called a normal good. Sometimes, when their income increases, people buy less bread, or less bus tickets (they buy a car instead). Here bread and bus tickets are called inferior goods. If the demand for a good decreases when incomes rise, this good is an inferior good. 3- Expected future prices. If everybody starts to expect the price of benzene to increase next week on Monday, what would they do? They would go and fill their tanks today. Demand for benzene today increases. Similarly, if everyone starts to expect the price of laptops to decrease next month, then your demand for laptops today decreases. People wait to buy laptops at a cheaper price. So a change in price expectations influence today’s demand. 4- Tastes, fashion. People demand more vegetables today because of health concerns. Similarly more spring water is sold today because most people do not drink tap water today. 20 years ago many people drank tap water and demand for spring water was very small. 5- Population growth causes demand for many goods to rise. Compare demand for cars in Turkey today and 20 years ago. 12 6- Season. Food demand increases during Ramadan, demand for airline travel increases during summer. Demand for electricity and LPG increase in winter. These effects are called seasonality. 2.3 Supply Supply is the total quantity of a good that sellers want to sell at every price during a given time period. Supply explains the behavior of sellers in a market. Quantity supplied of a good or service is the amount that sellers want to sell at a particular price during a given time period. Table 4 shows the supply of chocolate. Point Price Quantity supplied A 0.5 0 B 1.0 6 C 1.5 10 D 2.0 13 E 2.5 15 TABLE 4 price (liras/bar) supply of energy bars 3.0 2.5 E 2.0 D 1.5 C 1.0 0.5 B A 5 FIGURE 4 10 15 20 25 quantity supplied(million bars) 13 Law of supply: Other things constant, the higher the price of a good, the greater is the quantity supplied; and the lower the price of a good, the smaller is the quantity supplied. Change in supply: If one of the factors of supply other than price changes, then supply curve shifts. “Supply increases” means quantity supplied increases at every price. Point Price A B C D E TABLE 5 Quantity supplied 0 6 10 13 15 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Point A’ B’ C’ D’ E’ Quantity supplied 7 15 20 25 30 price (liras/bar) supply of energy bars 3.0 2.5 E new supply 2.0 D 1.5 C 1.0 0.5 B A 5 10 15 20 25 30 quantity supplied(million bars) FIGURE 5 Determinants of supply: Factors other than price that influences supply of a good. 1- Technological improvements, It becomes easier to produce goods. Increases supply. 14 2- Prices of inputs, If price of electricity is larger, what happens to the supply of bathrobes? If price of jet fuel increases, what happens to supply of airline tickets? Decreases supply. 3- Expected future prices: If the price of a good is expected to rise in the future, then supply decreases today and increases in the future. For example, if the food traders expect the price of olive oil to increase next month, then they store more olive oil and sell a small amount now. Because they can make much more profit next month. 4- The number of suppliers: Think of 10 years ago. Price of an air conditioner was more than 1000 USD. Today you can buy the same AC for 500 USD. This is because ten years ago only imported ACs were sold in Turkey. Today, many companies including Vestel and Arçelik are producing and selling ACs. So supply of ACs is much greater than 10 years ago. 2.4 Market Equilibrium: Equilibrium is a situation where quantity supplied equals quantity demanded in a market. In a free market, price balances demand and supply and brings the market to an equilibrium. Equilibrium price is the price at which quantity supplied equals the quantity demanded. Equilibrium quantity is the quantity bought and sold at the equilibrium price. Surplus Case For example, if the current price of potatoes is 0.5 lira/kg, and if the quantity supplied is 100 tons this week, and quantity demanded is 80 tons, then is this market at equilibrium? What do you expect to happen to the price? 15 This market is not at equilibrium because there is a surplus of potatoes. Only 80 tons of potatoes will be sold. When potato sellers cannot sell the remaining 20 tons, they start to cut price. Also potato farmers decrease potato production. When sellers cut prices below 0.5 lira, quantity demanded increases and surplus amount decreases below 20 tons. This process goes on until surplus amount becomes zero. So in case of a surplus, price decreases so that quantity demanded balances quantity supplied. Now, let us go back to the chocolates example. Table 6 and Figure 6 combines the demand and supply curves we have seen before. Price Quantity demanded 22 15 10 7 5 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 TABLE 6 Quantity supplied 0 6 10 13 15 Shortage (-) or Surplus (+) -22 -9 0 +6 +10 price (liras/bar) supply of energy bars 3.0 2.5 2.0 Equilibrium 1.5 1.0 demand for energy bars 0.5 5 FIGURE 6 10 15 20 25 quantity supplied(million bars) 16 Shortage Case Now let us assume that price of chocolate is 1 lira. At 1 lira, quantity demanded is 15 and quantity supplied is 6. This price is not an equilibrium price. So only 6 bars of chocolate is actually sold. There is a shortage of 9 bars of chocolate in the market. This means some buyers are willing to pay more than 1 lira for chocolate but there is no chocolate to buy. Some chocolate sellers see this opportunity and start to increase price and they can still sell it. So in case of a shortage, price increases to bring the market into equilibrium. Summary We have seen that when the market is not at equilibrium, price adjusts (decreases or increases) to bring the market into equilibrium. When there is surplus, sellers will cut prices to eliminate unsold stocks. When there is a shortage, then sellers will increase prices and some buyers are still willing to pay the higher price for chocolate. These processes show that price coordinates the plans of buyers and sellers so that market moves toward equilibrium. 2.5 Predicting Changes in Price and Quantity An increase in demand: See Figure 7 and Table 7. Starting from equilibrium position, let us assume that demand for chocolate increases for some reason. Maybe because it is the Valentine’s Day. At the current price of 1.5 lira, there is a shortage of 10 m chocolate in the market. This causes price to increase. When price increases, quantity demanded decreases and quantity supplied increases. Price increases until the shortage becomes zero. After some time, shortage is zero and the market is at equilibrium. New equilibrium price is 2.5 liras per chocolate and new equilibrium quantity is 15 m bars. 17 Price Old Quantity Demanded 22 15 10 7 5 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 TABLE 7 New Quantity Demanded 32 25 20 17 15 Quantity supplied 0 6 10 13 15 price (liras/bar) supply of energy bars 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 new demand 1.0 0.5 old demand 5 10 15 20 25 30 quantity supplied(million bars) FIGURE 7 Summary: When demand increases in the market, both market price and quantity sold increases. So if demand decreases in the market, the opposite happens; market price and quantity sold decreases. An increase in supply If food processing technology improves, then the supply of chocolate increases. See Table 8 and Figure 8. Price 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 Quantity Demanded 22 15 10 7 5 Old Quantity Supplied 0 6 10 13 15 New Quantity supplied 7 15 20 25 30 18 TABLE 8 price (liras/bar) old supply 3.0 new supply 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 5 10 15 20 25 30 quantity supplied(million bars) FİGURE 8 Since supply has increased, at the initial equilibrium price of 1.5 liras, there is a surplus of chocolate. This causes the price to fall. As the price falls, qty demanded increases and quantity supplied decreases. This causes the surplus to shrink. This process stops at the new equilibrium price of 1.0 liras. At the new eqbm, 15 m bars are bought and sold. So new equilibrium qty is 15 m bars. Summary: When supply of a good increases, its price decreases and its quantity sold increases. Ex: In Turkey, supply of ACs have increased in the last five years. AC prices have fallen a lot and qty of ACs sold have increased. Conversely, if supply of a good decreases, then price increases and qty sold decreases. There are 6 combinations of supply and demand changes. As an exercise, try to see what happens to equilibrium price and quantity in each case. 1- Change in demand, no change in supply, 2- Change in supply, no change in demand 19 3- Increase both in demand and supply 4- Decrease both in demand and supply 5- Decrease in demand and increase in supply 6- Increase in demand and decrease in supply 20 Chapter 3: Applications of Supply and Demand 3.1 Price controls: Government intervenes into free markets in the form of price ceilings and price floors. 3.1.1 Price Floor A price floor is a minimum price set and enacted by the government for a good or service. It makes the sale of a good or service below a certain price illegal. The Turkish govt. sets price floors for several food products. Some examples are hazelnuts, tobacco, tea and wheat. Why does the govt. have such a policy? In order to support the farmers. Usually, if a group of producers is a member of a union or they are a politically important group, they have greater bargaining power and force the government to policies that benefit its members. Figure 9 shows the effect of a price floor in hazelnut market. P liras/kg S 5 price floor 3 eqbm price D Q (kgs) surplus amount FIGURE 9: Price Floor For example, assume that the eqbm price for hazelnuts is 3 liras. For a price floor to have a real effect (be “binding”), it must be above the eqbm price. A price floor 21 below 3 liras would have no real effect on the market outcome. Let us assume that after negotiations between the govt. and hazelnut producers confederation, the price floor is set to be 5 liras/kg. This policy causes a surplus amount of hazelnuts as shown on the Figure. What happens to the surplus amount of hazelnuts? How does the govt. keep the price high and prevent the market from moving toward eqbm? By buying the surplus amount. Sometimes the govt. is able to sell this amount, but most of the time, sells it for a price a lot less than the price it has paid for it. This causes the govt. institutions like Fiskobirlik to have deficits. Who pays for these losses? The treasury pays, and so the taxpayers pay. Another price floor in the labor market is the minimum wage. By the same reasoning as above, minimum wage causes a surplus of labor which is also called unemployment. Show on the same figure. 3.1.2 Price Ceiling A price ceiling is a maximum price set and enacted by the government for a good or service. It makes the sale of a good or service above a certain price illegal. Consider the price ceiling for bread, 0.50 TL per loaf. Why does the government think a price ceiling is necessary? Govt. wants to support poor consumers through this policy. Figure 10 shows the effect of a price ceiling on bread. 22 P lira/loaf S 0.7 eqbm price price ceiling 0.5 D shortage amount Q (loaves) FIGURE 10 Assume the eqbm price of bread is 0.7 lira. A binding price ceiling must be below the eqbm price. Otherwise it would have no effect on the market. The result of the price ceiling is that there is a shortage of bread in the market. When there is a shortage of a good, it must be rationed with some kind of mechanism. Which buyers will be able to get the limited amount of bread? During the WWII years, bread was distributed with a “karne”, a ration coupon that gives every person a right to one loaf per day. If we assume that bread is distributed according to “first-come, first-served” principle as it is the case today, then people have to wait in line to get bread. Also, you cannot find the regular bread after 7pm in the evening. This is because the bakeries do not want to sell the cheap bread; they bake only a limited quantity. They bake other types like francala that there is no price restriction and so more expensive. So price ceilings have unwanted consequences like this. Rent ceiling: Good for the poor. Show the short term and long term effects by drawing two supply curves. In the short term, supply curve is steep because it is difficult for houseowners to respond to the policy quickly. In the long term, available 23 housing for rent may decrease as houseowners start to use their houses for other more profitable purposes. This is an example of unwanted consequences of price controls. P (liras/ month) SRS LRS 700 eqbm rent rent ceiling 500 D LR shortage Q (loaves) SR shortage FIGURE 11 Shortage of houses available for rent increases in the long term. We will have similar results if the government decides to enact a law that restricts the rate of increase of rents, like 5% per year. Normally rents increase faster than the rate of inflation in Turkey. There will be a shortage of houses available for rent, at least in the long term. 3.2 Elasticity of demand: Elasticity measures the sensitivity (responsiveness) of quantity demanded to changes in price and income. We are looking at the law of demand in more detail by measuring elasticity. Law of demand says that as price of the good increases, qty demanded decreases, but how much does it decrease? We did not consider the magnitude of the price change on demand. Here we will quantify this effect formally. 24 3.2.1 Price Elasticity of Demand Price elasticity of demand (PED) measures the sensitivity of quantity demanded to changes in price. PED is defined as the percentage change in the quantity of a good demanded divided by the corresponding percentage change in its price. PED Point % change in qty demanded % change in price Price (lira/ticket) A B C D E F G TABLE 9 125 100 75 62.5 50 25 0 Quantity of tickets demanded (1000) 0 20 40 50 60 80 100 Price Elasticity of Demand price (liras/ticket) 125 A B 100 C 75 E 50 F 25 G 0 FIGURE 12 20 40 60 80 100 quantity demanded (1000 tickets) -4 - 1.5 -1 - 0.67 -0.25 25 Example: Consider Table 9. This is the number of football game tickets for, say, Galatasaray. Verify PED numbers in column four. Explain slowly how to calculate percentage changes. Percentage change of x y is calculated by y x *100 . x AB Price change of 125 100 is a percentage change of (-25 / 125) * 100 = -20%. Corresponding Qty change of 0 20 is a percentage change of (20 / 0) * 100 = . Then PED = . BC Price change: 100 75 is (-25 / 100)*100 = -25% Qty change: 20 40 is (20/20)*100 = 100%. Then the PED = 100/-25 = -4. DE Price change: 62.5 50 is (-12.5/62.5)*100 = -20% Qty change: 50 60 is (10/50)*100 = 20% . Then PED = -1. Demand is elastic if |PED| > 1. Demand is inelastic if |PED| < 1. Demand is unit elastic if |PED| = 1. In our example, demand is elastic through points A, B and C. Demand is inelastic through points E, F and G. Demand is unit elastic at point D. Why is elasticity important? Consider yourself as a manager of a football club, say Galatasaray. Table 10 shows demand for tickets and total revenue. Your objective is to maximize Total Revenue from ticket sales where Total Revenue (TR) = Price (P) X Number of tickets sold (Q) 26 Price (lira/ticket) 125 100 75 62.5 50 25 0 Quantity of tickets demanded (1000) 0 20 40 50 60 80 100 Price Elasticity of Demand Total Revenue -4 - 1.5 -1 - 0.67 -0.25 0 2000 3000 3125 3000 2000 0 TABLE 10 Where should you pick the ticket price in order to maximize revenue? Assume initially tickets are 100 TL. Should you decrease or increase ticket prices? If you increase price to 125 TL, nobody will buy tickets and revenue is zero. If you decrease price to 75 liras, total revenue increases because the number of tickets sold increases faster than the decrease in price. This means buyers are very sensitive to the price cut. |PED| > 1 because: %change in qty demanded > %change in price. Notice that there is a close relationship between elasticity and total revenue: 1- When demand is elastic; |PED| > 1, the manager should decrease the price to increase TR, 2- When demand is inelastic; |PED| < 1, the manager should increase the price to increase TR, 3- TR is maximized when |PED| = 1. At this point, if you increase or decrease price (a small amount), TR is unchanged. Other Examples: Agricultural products, crude oil and houses have inelastic demand. Tourism expenditures, cars, furniture have elastic demand. Table 11 shows some real world elasticities. 27 Price Elastic Demand Metals Electrical Engineering Products Mechanical Engineering Products Furniture Motor Vehicles Transportation services 1.52 1.39 1.30 1.26 1.14 1.03 Price Inelastic Demand Gas, Electricity and Water 0.92 Chemicals 0.89 Drinks 0.78 Clothing 0.64 Tobacco 0.61 Banking and Insurance 0.56 Housing 0.55 Agricultural and Fish Products 0.42 Books, Magazines, newspapers 0.34 Food 0.12 Oil 0.05 TABLE 11: REAL WORLD PRICE ELASTİCİTİES OF DEMAND Sources: From M. Parkin’s Economics who compiled from: Ahsan Mansur and John Whalley, “Numerical Specification of Applied General Equilibrium Models: Estimation Calibration and Data”, in Applied General Equilibrium Analysis, eds. Herbert E. Scarf and John B. Shoven (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 109, and Henri Theil, Ching-Fan Chung and James L. Seale, Jr. Advances in Econometrics, Supplement I, 1989, International Evidence on Consumption patterns (Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press, Inc., 1989) and Geoffrey Heal, Columbia University, Web site. What Determines Price Elasticity? 1- Ease of substitution: Is it easy to substitute insulin or a vacation to Greece? 2- Width of the market definition: If the price of all cigarettes increases by 10 percent, does the quantity demanded decrease by 20% or 5%? Probably by 5% because it is hard for consumers to substitute some other good for cigarettes. Now consider a particular brand of cigarettes, say CAMEL. If the price of Camel cigarettes increases by 10 percent, does the quantity demanded decrease by 5% or 20%? Probably by 20%. Because it is easier to substitute another cigarette brand for Camel than to substitute ALL cigarettes. If we define a narrower market, price elasticity increases than a wider market. 28 3- Time that has passed since Last Price Change: In the long-term, demand is much more elastic than in the short-term. To illustrate the importance of the difference between short term and long term responses, let us consider the 1973 oil crisis. Oil price shock of 1973-74 OAPEC (Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries) agreed to restrict oil supply to U.S. and Western Europe in response to 1- Western pressures for cheap crude oil, 2- Their support for Israel. Figure 10 shows the short-term and long-term effects of this. price (dollars/barrel) price (dollars/barrel) A D S’ S’ S S D D S’ S 0 S’ D quantity 100 demanded (barrels) inelastic demand(a) S elastic demand(b) FİGURE 13: Elastic and inelastic demands In the short-term (1 year), price of crude oil had quadrupled by 1974. This is because demand for oil is very inelastic in the short term, elasticity is around 0.05. As shown on part (a) of Figure 13, the decrease in the supply of crude oil led to a large increase in its price but a small decrease in qty of oil sold. This means that the revenue of OPEC countries increased very sharply 1 year after the oil embargo. 29 But in the long-term as the time passed, consumers were better able to substitute away from oil by buying smaller cars, use public transportation, and use alternative energy sources such as natural gas, nuclear power, wind and water. Use paper bags instead of plastic bags, etc. Demand is much more elastic in the long-term than in the short-term. So in the long-term, the demand curve is much flatter as in part (b) of Figure 10. As a result, the same fall in the supply of oil produced a small price increase but a large decrease in qty of oil sold in the long-term. Then the OPEC revenues decreased a lot as time passed. The real price of crude oil decreased back to levels close to the pre-crisis levels in 1986. Another factor that contributed to the revenue decline was that oil production made by non-OPEC countries significantly increased in the long-term. This response by non-OPEC countries made the long-term supply of oil more elastic. OPEC revenues decreased further. It was easier to keep prices high in the SR than in LR. Year: Crude oil price change % 73-74 50 79 14 80 34 81 34 82 -10 83 -10 84 -10 85 -10 86 -45 30 “Can good news for farming be bad news for farmers?” Consider market for wheat. Wheat has an inelastic demand. Assume initially the market is at eqbm. Now, suppose Fatih Uni. professors have found a two times productive wheat seed. Also suppose that all farmers use this new seed and are farming two times the old amount. Supply curve will shift right. The new eqbm will be at some point with a lower price and a higher qty. This is good for consumers because they are able to buy wheat & bread cheaper. But is this good for wheat producers? The answer depends on PED. Unfortunately, TOTAL REVENUE earned by all farmers DECREASES because PED for wheat is only 0.24. When price falls by for example, 20%, qty demanded will increase by only 4.8%. Farmers will earn less money in total and on average as a result of technological improvement. The only solution is to employ less labor in agriculture. At this point, you may ask “why do the farmers adopt the innovation and increase supply?”. They do because the decision facing each farmer is whether to increase her crop taking PRICE of wheat AS GIVEN. The farmer does not take into account the effect of her actions on the market price for wheat. Since all farmers face a similar choice of action, they all decide to increase production. As a result they earn less money. The inelastic demand for agricultural products explains two observations: (i) every year, the percentage of labor force working in agriculture falls in many countries including Turkey: in US, it fell from 17% in 1950 to 2% in 2000. This is because as production increases, price falls fast, revenues fall, and average income falls. 31 (ii) EU subsidies on agriculture: EU pays farmers to leave part of their lands unplanted in order to keep supply low and prices high. Of course, this policy hurts consumers and the society. It only benefits the farmers. 3.2.2 Income elasticity of demand Income elasticity of demand is defined as the percentage change in the quantity of a good demanded divided by the percentage change in consumers’ income: IED % change in qty demanded %change in income Consider demand for tomatoes, laptop computers and bus tickets. Which one do you think has a larger income elasticity of demand? Consider the case when your income rises from 1000 liras a month to 5000 liras a month. How much does your demand for tomatoes increase? How much does your demand for a trip to Paris increase? How about bus tickets? Luxury goods have an IED larger than one. Airline travel is a luxury good. Necessity goods have an IED less than one. Tomatoes, tobacco, clothing are necessity goods. Normal goods have a positive income elasticity of demand. Most goods are normal. Inferior goods have a negative income elasticity of demand (IED). Bus tickets are examples of inferior goods. Table 12 shows some real world income elasticities of demand. 32 Income Elastic Demand Airline travel Movies Foreign travel Electricity Restaurant meals Haircuts Automobiles 5.82 3.41 3.08 1.94 1.61 1.36 1.07 Income Inelastic Demand Tobacco 0.86 Alcoholic Drinks 0.62 Furniture 0.53 Clothing 0.51 Newspapers and Magazines 0.38 Telephone 0.32 Food 0.14 TABLE 12: REAL WORLD INCOME ELASTICITIES OF DEMAND Source: From M. Parkin’s Economics who compiled from H.S. Houthakker and Lester T. Taylor, Consumer Demand in the United States (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1970) and Henri Theil, Ching-Fan Chung and James L. Seale, Jr. Advances in Econometrics, Supplement I, 1989, International Evidence on Consumption patterns (Greenwich, Conn.: JAI Press, Inc., 1989) 3.2.3 Cross-price elasticity of demand The Cross-price elasticity of demand for good i with respect to changes in the price of good j is: CPED (i, j) % change in qty of good i demanded %change in price of good j Substitute goods have positive cross-price elasticity of demand. LPG and benzene are substitute goods. When price of benzene goes up, quantity of LPG demanded increases. Complement goods have a negative cross-price elasticity of demand. Cars and benzene are complement goods. When price of benzene goes up, all other things kept constant, demand for cars decreases.