ENGL 150 Paper.doc

advertisement

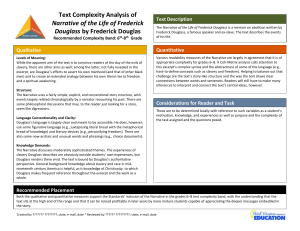

Michelle Kasprak ENGL 150 30 March 2010 Early America: Idealism, Dreams, and Reality Americans have long placed importance on particular ideals such as freedom, education, material and social wealth, and equal opportunity. Early foundations for the American dream were seen in writings by early colonial leaders such as John Smith, and were further perpetuated by founding fathers such as Benjamin Franklin. However, along with the pride evoked by these values came the hypocrisy of realizing how the American dream only applied to select groups of citizens. Frederick Douglass and Fanny Fern are two 19th Century writers who show how African-Americans and women were two groups in particular that were excluded from the ideals of independence and equality. In “A Description of New England,” John Smith says “What to such a mind can be more pleasant, than planting and building a foundation for his posterity, got from the rude earth, by God’s blessing and his own industry, without prejudice to any?” (66). Smith is trying to lure English settlers to the colony by describing how they can, in a sense, start anew and be a part of the development of a new land where their children and future family members can thrive. He is describing to the reader how there can be no harm in doing so; he even poses the idea, “What so truly suits with honor and honesty, as the discovering things unknown?” (66). This also appeals to the reader’s sense of adventure and discovery. English settlers in the New World will have the chance to explore the unknown territory and make it their own. These themes of adventure, exploration, and being able to provide a better life for one’s family are early linkages to the concept of America as the land of opportunity and the idea of the rugged American who is not afraid to take on new challenges. Kasprak 2 Smith continues on to describe the natural abundance of New England. He discusses how pleasure can be found in planting one’s own fields, fishing, and hunting. He states that, “If a man work but three days in seven, he may get more than he can spend, unless he will be excessive” (68). Smith is implying that if a colonist is reasonable, he can work less but still have plenty. This shows how America began as a vision of a place where people could find ample resources and gain material wealth somewhat quickly. It is important to note that even though Smith emphasizes the material gain that can be achieved in the New World, this gain will not come without at least some labor; a settler must be willing to work for his riches. He expresses early ideas of America as the land of plenty, yet also plays into the future American value of working to achieve one’s goals. Benjamin Franklin’s autobiography shows the progression of American ideals from the 15th to the 16th Century. In one section of his autobiography, Franklin describes how he started a library. Franklin’s account of how he began the library and how he was able to utilize it to further educate himself reveals a persona of one who is dedicated to hard work and study. Franklin seems to place a high emphasis on intelligence and sees the enhancement of one’s intellect as a way to better one’s status. As he states with regard to growth of the library system, “Reading became fashionable, and our People…in a few Years were observ’d by Strangers to be better instructed and more intelligent that People of the same Rank generally are in other Countries” (523). Franklin is showing how the library inspired others to read, and through this they were able to better their own knowledge. He boasts that because of this, the people of America started to become noticed for their superior knowledge. Franklin also shows how the library advanced his own studiousness, saying that, “The Library afforded me the Means of Improvement by constant Study…and thus repair’d in some Kasprak 3 Degree the Loss of the Learned Education my Father once intended for me. Reading was the only Amusement I allow’d myself” (524). Franklin not only establishes a library, but he also uses it to exercise self-discipline by spending his time there reading instead of going to taverns or other places where he could be entertained with less benefit to his industrious behavior. He continues to place importance on the value of industry by describing how he continued with his business and did what was necessary to provide for himself and his family; he even mentions how he is fortunate to have a wife just as dedicated to “Industry and Frugality” as he is (524). Like Smith, Franklin suggests that hard work will reap great benefit, but in this case the benefit lies with oneself and also the general public. The concept of doing things for the advantage of everyone in society is coming through. Education is a new, yet important American value that Franklin stresses, as well, especially the idea that education can be a means for social mobility. When discussing his views of religion, Franklin is seen by readers as a man of independent thought who is not ashamed to follow his own doctrines. For example, when Franklin is talking about the views of the church that he does not agree with, he states that, “And tho’ some of the Dogmas of that Persuasion, such as the Eternal Decrees of God, Election, Reprobation, etc., appear’d to me unintelligible, others doubtful…” (525). Franklin is not hesitant about distancing himself from the religious ideologies that he does not agree with. He continues by describing a preacher friend of his who would urge him to go to church more often, responding to this notion by saying, “Had he been, in my Opinion, a good Preacher perhaps I might have continued” (524). Franklin does not shy away from this honesty. He feels that he should be free to choose what he believes in, and by deciding not to attend church he is thinking for himself. In these ways he embodies the virtues American freedom and independence. His value on industry also is reinforced later when he says that he would use Sundays to study. Kasprak 4 Despite the pride that came along with the idea of America as a land of opportunity, with high value being placed on principles such as independence, education, and hard work, the treatment of many living in the U.S. served to contradict this American idealism. Frederick Douglass and Fanny Fern are two writers of the mid-19th Century who revealed these contradictions in their works. Frederick Douglass was a former slave who first published his autobiography in 1845, and through discussing his experiences as a slave, Douglass shows how African-Americans were excluded from the concept of the American dream. As slaves, African-Americans were not free, and most were denied education. African-American slaves had no property or social mobility, and families were torn apart at slave auctions. This was a direct contrast to the idea that America was a country where one could hope to secure a better future for their posterity. In the beginning of his autobiography, Douglass describes how he was separated from his mother as an infant and only saw her a few times in his life before she died. As he says about her death, “I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger” (2040). Here, the reader sees an example of how many slaves did not even share an emotional connection with their own family members because of this forced separation. Douglass also talks about how the rumor was that his master was his father, declaring that, “The children of slave women shall in all cases follow the condition of their mothers; and this is done too obviously to administer to their own lusts, and make a gratification of their wicked desires profitable as well as pleasurable” (2041). In this passage, Douglass shows how slavery severely twisted the American idea of family by describing a system where slaves were often the children of their masters, who would profit from the brutal labor of their own children. Kasprak 5 Douglass also points out how slaves were not allowed to learn how to read and write, for fear that educated slaves would begin to challenge their status and incite rebellion. He talks about how when he was a boy, Mrs. Auld, one of his masters, began to teach him the ABC’s and how to spell words. Upon learning that his wife was teaching Douglass to spell, Mr. Auld reprimanded her saying, “’if you teach that nigger how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. It would make him discontented and unhappy’” (2054). Of course, these words only encouraged Douglass even more, and he began trying to learn words from little white boys he talked to in the streets of Baltimore; his eventual ability to read and write did help inspire him to seek freedom. Douglass began reading documents related to slavery and abolition, and as he states, “The more I read, the more I was led to abhor and detest my enslavers” (2057). Douglass was one of the more fortunate slaves who was able to learn how to read and write, but most were never allowed to do so. Even knowing how to read was risky and could mean life or death in some cases. By being withheld from this basic knowledge, many African-Americans were also being denied the ability to learn and think for themselves. Even though America was the land of the free, it was clear that this freedom was only intended for non-slaves. Fanny Fern was a female writer during the 19th Century who used humor and sarcasm as a way to bring to light some of gender inequality that she saw around her. Targets of her criticism include domestic advice given to women and male book reviewers, as presented in two magazine articles entitled “Hungry Husbands,” and “Fresh Leaves, by Fanny Fern.” In “Hungry Husbands” she uses a tone that mocks that of someone giving guidance to docile housewives in order to make their husbands happy. For example, when explaining what wives should do when they want to get permission from their husbands to do certain things, like to go on a vacation, Kasprak 6 she urges her readers to “Strike while the iron is hot…Should he demur about it, the next day cook him another turkey, and pack your trunk while he is eating it” (1795). The kind of husband portrayed in Fern’s writing is extreme; as Fern says, “There’s nothing on earth so savage- except a bear robbed of her cubs- as a hungry husband” (1796). Even though this piece is laced with sarcasm, through the satire the reader can see that Fern is actually challenging the notion that “The hand that can make a pie is a continual feast to the husband that marries its owner” (1795). Her tone and language ridicule the idea that women should be content in their subservient roles and that women should be willing to do what they must in order to make sure their husbands will be more generous to them. As she says, “Yes, feed him well, and he will stay contentedly in his cage, like a gorged anaconda” (1796). “Fresh Leaves, by Fanny Fern” is a spoof of what Fern thinks could be said by book critics about Fern and her writing. It becomes clear through her language that Fern is aware of the demeaning nature of her male reviewers towards women writers, and the demeaning nature of men to women in society in general. As she says, writing from the stance of a male book reviewer, “We imagine her, from her writings, to be a muscular, black-browed, grenadierlooking female, who would be more at home in a boxing gallery than in a parlor- a vociferous, demonstrative, strong-minded horror- a woman only by the virtue if her dress. Bah! The very thought of it sickens us” (1801). By parodying the debasing views that men hold of women, Fern is able to expose this social injustice to her readers and assert her own feminism. The tone of the article is mock-patronizing towards women. A good example of this would be when Fern writes, “When we take up a woman’s book we expect to find gentleness, timidity, and that lovely reliance on the patronage of our sex which constitutes a woman’s greatest charm” (1801). Throughout the work there are references to the idea of a woman’s place being in the home, Kasprak 7 where she can serve and rely on men. Fern states, “Thank heaven! there are still women who are women- who know the place Heaven assigned them, and keep it” (1801). Through the parody and tone the reader gets a sense of how ridiculous the injustice really is. Fern’s sometimes scathing humor shows how women were not considered to be equals by their male counterparts, and they were expected to be submissive and obedient to men. In this sense, women could never hope to fully embody American principles related to intelligence and independence. Even though early colonists like John Smith and Benjamin Franklin suggested that America was a country where one could find material abundance and social mobility if he was willing to remain diligent, the enslavement of African-Americans and the subjugation of women were glaring contradictions to American idealism. Frederick Douglass and Fanny Fern are just two examples of numerous writers in American history who tried to bring these hypocrisies into focus. They wanted to show that the American dream was, in fact, a far cry from the American reality. Kasprak 8 Works Cited Baym, Nina, editor. The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Volume B. New York: W.W. Norton, c2003. Print. Frederick Douglass- Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass Fanny Fern- “Hungry Husbands” and “Fresh Leaves, by Fanny Fern” Baym, Nina. The Norton Anthology of American Literature, Volume A. New York: W.W. Norton, c2007. Print. John Smith- “A Description of New England” Benjamin Franklin- The Autobiography