Understanding Antitrust through the Eyes of Walmart.doc

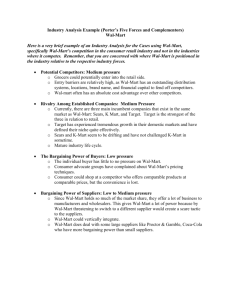

advertisement