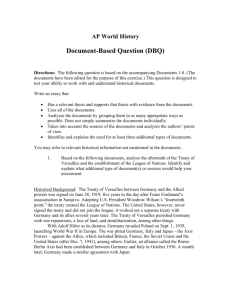

4.14 The Senate Debates the League of Nations

advertisement

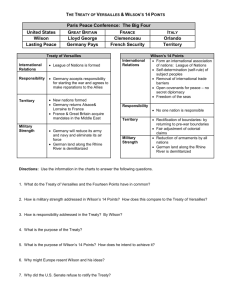

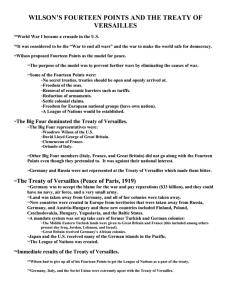

Name __________________________ Date: ________________ Section: 11.1 11.2 (circle one) U. S. History II HW 4.14: The Senate Debates the League of Nations Instructions 1. Carefully read and annotate the following text. (Source: Adapted from Choices for the 21st Century Education Program, To End All Wars: World War I and the League of Nations Debate, Providence, RI: Watson Institute for International Studies, 2006.) 2. Define the following terms in your own words, using a dictionary or drawing inferences from the context of the reading: a. Sovereignty b. Ratification c. Isolationism 3. Answer the following questions in complete sentences. a. How was the League of Nations supposed to prevent another world war? b. What was Article X of the League of Nations Covenant? Why were some Senators concerned about Article X? c. Why would Lodge and other Republican Senators drag out the debate over the Treaty of Versailles? What was their goal in doing this? d. Why did Wilson decide to go on a nationwide trip to promote the Treaty of Versailles? What was his goal in doing this? e. What did each of the three major groups in the Senate (described under “Options in Brief”) want to do about the Treaty of Versailles? Why? Explain each group’s reasoning. Background At the Paris Peace Conference, one of US President Woodrow Wilson’s major goals was to establish a League of Nations – an international organization whose member countries would agree to defend each other if they were invaded or if another country tried to take away territory guaranteed to them by the Treaty of Versailles. The participants at the Paris Peace Conference would ultimately agree to create a League of Nations, but Wilson alone could not get the United States to join the League. Instead, at least two-thirds of the United States Senate would have to vote to approve the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations. Many senators were less enthusiastic than Wilson about the League of Nations. Wilson in Paris (continued from HW 4.12) How did Senators react to the covenant? Wilson knew the specifics of the League of Nations Covenant [founding agreement] would face resistance at home in the Senate… Wilson invited members of the Senate and House committees on foreign affairs to dine with him at the White House [on February 26, 1919], where he provided them a draft of the entire proposed covenant of the League. Some Republican Senators thought that the League of Nations would threaten the Monroe Doctrine (designed to limit European involvement in North America) as well as diminish the freedom of the United States to choose how it wanted to act overseas. The United States, Wilson replied, should relinquish [give up] some of its sovereignty [control over its own affairs] to benefit the world community. Many of his guests did not agree. What was Article X of the League of Nations Covenant? At the heart of the covenant was Article X, which spelled out the new “collective security” arrangements. Many felt that Article X would obligate the United States to intervene overseas. Article X stipulated [provided] that all states would respect the territorial integrity of the borders drawn at Versailles and that the League of Nations would act to maintain them against aggression. The League would safeguard these new postwar borders through economic sanctions as well as through the use of military force. Wilson saw this approach as a moral and responsible move away from the traditional power politics that had led to the catastrophic destruction of the Great War. On the day before Wilson returned to Paris, Senator [Henry Cabot] Lodge [a Republican senator from Massachusetts, the chairman of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, and a longtime opponent of President Wilson] circulated a document to his colleagues stating that he rejected the draft covenant. He asked that the peace conference set aside the question of the League of Nations until the completion of a peace agreement with Germany. Thirty-nine Senators signed the document indicating their agreement with Lodge’s statements. This was more than enough signatures to deny Wilson the two-thirds majority needed to ratify the treaty. The Treaty at Home Despite Wilson’s resounding faith in the creation of the League of Nations and other agreements that came out of the Paris Conference, Americans had numerous questions about the decisions made there. Though there were many, particularly Democrats, who unhesitatingly advocated American membership in the League—among them teachers, members of the clergy, and others who favored a rapid restoration of peace—others had their doubts. Some doubters wondered if the League of Nations would have the power to implement its decisions and to put a stop to aggressors. Others felt the League of Nations Covenant was too liberal and too internationalist. They argued that it would compromise the sovereignty of the United States and entangle U.S. soldiers in the conflicts of far away places… How was the treaty received in Congress? Though the outcome of the Paris Peace Conference was a topic of great discussion and disagreement throughout the United States, nowhere was it as hotly debated as it was in the Senate. When Wilson set sail back to America after signing the Versailles Treaty, he did not realize that the struggles he experienced with the Big Four would pale in comparison to the fight he was about to have with members of the United States Senate. Storm clouds had been gathering for months over what the treaty meant for America’s foreign policy. Fall 1919: The Moment of Decision Wilson submitted the Versailles Treaty to the Senate in July 1919. The election results in 1918 had brought a Republican majority to Congress, which meant that Republicans could control the pace of debates. Many Republican Senators, Lodge foremost among them, hoped to drag out the proceedings so that the public would become disengaged and withdraw its support of the treaty. Senator Lodge began deliberations on the treaty by reading it out loud, which consumed two weeks. The Senate Foreign Relations Committee also held public hearings for six weeks in another attempt to slow the process… At ten o’clock in the morning on August 19, 1919, members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee gathered with President Wilson in the East Room of the White House. Wilson perceived that enough opposition to the treaty existed in the Senate to prevent it from being ratified [approved] by the required two-thirds majority. During the meeting he attempted to explain the covenant and the obligations of the United States under the League, hoping that he could persuade them to vote in favor of its ratification. The meeting lasted over three hours but did nothing to sway the Senators. Unable to convince the Senate Foreign Relations Committee of his views, Wilson opted to go on a nationwide trip where he hoped to explain the League of Nations to the American people and put pressure on doubting Senators. On September 3, 1919, President Wilson set off on a whirlwind tour, giving forty speeches in the space of twenty-two days… However, the pace of the trip, coupled with his preexisting medical problems, proved to be too much for Wilson physically… On October 2, Wilson suffered a stroke. Incapacitated [unable to work] and partially paralyzed, Wilson was unable to continue his campaign to engage the American public on the Senate ratification debate. From his bed, Wilson sent notes to members of the Senate, urging them to support the League. In November, the Senate met to debate and vote on the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and its controversial League of Nations, which made up the first 26 of 440 articles. The Senate had fallen into three distinct groups. One group supported the treaty as it stood, one group sought to make changes to it in order to maintain the power to act unilaterally [without consulting other countries] in foreign affairs, and one group hoped to reject it altogether, preferring to isolate the United States from European issues. Options in Brief Option 1 – Progressive Internationalists: Support the Treaty The Great War [World War I] has taught us that reliance on isolationism [the belief that America should not get involved with the rest of the world] and a unilateral foreign policy is no longer feasible. Because of these changes and the fact that our old buffers of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans can no longer shield us from the rest of the world, we must accept the mantle of leadership that has been thrust upon us. The League of Nations will insure the peace by providing economic, legal, and security organizations to address global problems. This “general assembly of states” will offer a place for nations to come together and discuss issues and complaints with other members in order to solve problems before conflict occurs. The League is essential to the peace of the world, and we must support it. Option 2 – Reservationists: Make Changes to the Treaty The Great War demonstrated that the world is a dangerous place where nations base their actions solely on their own interests. The terms of the Versailles Treaty do not guarantee that international relations have changed. Accusations that we are isolationist are completely false. We support America playing an active role in the new world order, however, long-held traditions governing American foreign policy, such as “avoiding foreign entanglements,” are just as true today as they were before 1914. Article X, with its declaration that all members would be obligated to enforce postwar borders, violates this principle. The Versailles Treaty also provides for too many instances in which a body other than Congress makes laws concerning the citizens of the United States. We suggest making changes to the treaty to resolve these flaws. Option 3 – Irreconcilables: Reject the Treaty Because of Europe’s incessant [never-ending] wars over ancient hatreds and power politics, it has always been in our interest to separate ourselves as far as possible from that volatile [unstable] continent. President Wilson’s attempt to make “the world safe for democracy” was doomed from the start. Those who put any faith in “collective security” through the proposed League of Nations are deluding themselves. Membership in any such organization would risk our security and embroil us in constant wars. Have we not learned from our mistakes? The time has come to cut off our relationship with the troubled continent of Europe. We should not ratify the Versailles Treaty.