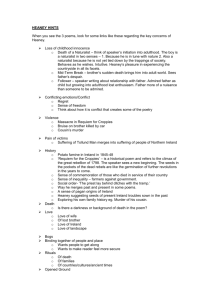

Poetry (Nick Mitchell)

advertisement

Was it a sense of belonging or a feeling of isolation that dominated the poetry you studied? The poetry of William Blake, Robert Frost, Seamus Heaney, Sylvia Plath, and William Wordsworth is dominated by an atmosphere of isolation. Each poem reflects a different form of isolation, arising from the situational discourses used to express their speakers’ emotions and the causes of their isolation. These discourses vary between the broad concepts of nature and society, which the poets observe from their own unique perspectives, to narrower contexts like the family. In each case the speaker is trapped in their isolation and must escape through their poetry. The natural world is one specific subject of isolation in the poetry of William Wordsworth and Seamus Heaney. In Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” the speaker reflects on the beauty of nature, observing a field of daffodils ‘fluttering and dancing in the breeze’. The sight makes him feel ‘gay/In such a jocund company’, but he has no active role in the sight; he is simply an observer who ‘gazed-and gazed with little thought’, only in his heart he can dance with the daffodils. Wordsworth has his own personal image which he finds in ‘the bliss of solitude’ when he can dream to be part of the scene. The solitude of the poem is peaceful and fulfilling, implied by the poem’s iambic tetrameter and rounded soft sounds. Seamus Heaney’s “Death of a Naturalist” contrasts Wordsworth’s response to nature with a naive and fearful attitude towards the environment. The poem displays two reasons for the speaker’s isolation from nature, divided between the two stanzas. In the first stanza, the speaker is isolated from nature by a naive and idealised point of view, while in the second stanza he isolates himself out of fear, after being ‘sickened, turned’ by the true personality of the frogs ‘when fields were rank’. This change is reflected by the enjambment of ‘A coarse croaking that I had not heard/Before”, the speaker’s brief afterthought emphasising the sanitised nature of his previous experiences. The entire imagery and sound of the poem changes between the two stanzas as the isolation grows; from the first stanza’s focus on the soft-sounding ‘warm thick slobber of frogspawn’ to the speaker being transfixed by harsh ‘gross-bellied frogs’ in the mature second stanza. The personification changes from peaceful ‘nimble-swimming tadpoles’ to terrifying ‘great slime kings...gathered there for vengeance’. By the conclusion, the speaker is forever transformed by his isolation. The conflicting ideas of “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” and “Death of a Naturalist” both share a common conclusion: humanity is forever separated from the natural world. Nick Mitchell Robert Frost conveys a more neutral isolation in “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”, as he focuses on humanity’s lack of observation of nature, and separating us from it as a result. Frost complains that social preoccupations prevent him from taking time to observe ‘the darkest evening of the year’, and he will remain unable to enjoy watching the ‘woods fill up with snow’. The opposite, however, occurs. Frost slowly loses focus on his task and is seduced by the ‘easy wind and downy flake’, paralleled by the change in rhyme scheme from AABA-BBCB to CCDC-DDDD. Eventually he is totally spellbound by the atmosphere around him, as evidenced by the concluding couplet’s repetition. The poem comments on humanity’s isolation from nature by paradoxically isolating the speaker from society. Robert Frost continues his discussion of isolation in “Mending Wall”, campaigning for change against the isolated nature of human society, a similar theme to William Blake’s “London”. The free-spirited speaker of “Mending Wall” explores his realisation of a wall’s lack of necessity, both physical and social, and tries to simultaneously enlighten the other character. The second man holds onto tradition and ‘will not go behind his father’s saying’. Frost evokes his speaker’s desired freedom through blank verse and a conversational and light-hearted style, such as in the pun ‘to whom I was like to give offence’. Despite Frost’s attempts, the second man ‘like an old-stone savage armed’, a symbol of society’s persistent rigidity, refuses to incorporate Frost’s ideas leaving him separated by the now metaphorical wall. “London” also places the speaker against society as a whole, although Blake’s speaker’s perception of separation is too intense to be broken down. Throughout the poem the speaker detects traces of the scars of society: the ‘blackning Church’ and ‘the hapless soldiers’ sigh’ reveal the hypocrisy and failures of religion and the state. The most explicit failure of society referenced by Blake is the standards of males’ sexual behaviour, allowing prostitution to ‘blight with plagues the Marriage hearse’ through venereal disease. The constant use of synecdoches and vague descriptions create a separation between Blake’s speaker and the city, as he struggles to free himself from ‘the mind-forg’d manacles’ of the Industrial Revolution. He does not leave the city streets: despite his moral isolation, he will continue to endure the horrors of ‘each charter’d street’, the double meaning identifying both the physical and legal restrictions of London’s environment. In both “Mending Wall” and “London”, the speakers are isolated from, but entrapped by, the cultures in which they live. A more localised isolation can be found in Seamus Heaney’s “Digging” as Heaney isolates himself from his ancestors’ career choice, but also attempts to emulate his forefathers’ strengths. From the opening of the poem, Heaney’s pen rests ‘snug as a gun’, a simile Nick Mitchell confirming his masculinity, but clearly separating himself from his father as illustrated through the ironic enjambments of ‘I look down/Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds/Bends low’ as Heaney reflects upon the distance of their lives. The use of free verse, breaking out from the monotony of the laborious tasks Heaney’s ancestors lived by, and the discomfort created by the onomatopoeic sibilance of Heaney’s imagery, like ‘the squelch and slap/Of soggy peat,’ demonstrates his rejection of manual work, despite the admiration he feels for his ancestors. In the penultimate stanza, Heaney admits ‘I've no spade to follow men like them’, and he moves on towards his own individual path. His opinion of his forefathers, however, has developed over the poem from a pretentious disapproval to a humble respect. The opening simile of the pen becomes an intimate metaphor in the final line, reflecting how Heaney bridges the isolating gap between himself and his family. The theme of manual labour is also featured in Robert Frost’s “Out, Out-” to explore familial isolation, but with the extra element of death. When the boy dies, the family simply ‘turned to their affairs’ without a moment of remembrance for the child. The carelessness is demonstrated by the poem’s structure, developing the plot to a major climax but then finishing with a fast resolution. Frost suggests that the selfish nature of humanity leads to an isolated and cold view of others, with everyone, even families, only observing rather than truly connecting with each other, evident by the third-person narration of the poem. William Blake’s “Infant Sorrow” conveys the same sense of hopeless isolation, from the point of view of an infant speaker describing their birth and contemplating their destined life. Blake immediately establishes that neither the parents nor the child have any desire for the other, with the child already demonstrating the inherent self-invoked isolation as he is ‘struggling in my fathers hands:/Striving against my swadling bands’. The familial isolation of “Out, Out-” and “Infant Sorrow” suggests that isolation is inherently part of the human condition. Just like the baby in “Infant Sorrow”, Sylvia Plath struggled against her father, as she details in “Daddy” and escapes from in “Lady Lazarus”. In “Daddy”, Plath describes how she has attempted to live in her childhood memories of her father “barely daring to breathe or Achoo”. Her entrapment in her childhood is supported not only by the black shoe metaphor but also the repetition of the childish “oo” sounds found throughout the entire poem, alluding to nursery rhymes. She cannot get past her childhood and truly connect herself to him, resorting to vagaries in desperation, a desperation that is recreated through the repetition of key phrases, suggesting that the speaker is crying out. Plath attempts to isolate herself from everything but her father; removing herself from society as ‘the black telephone’s off at the Nick Mitchell root’, trying to turn away from herself and ‘get back, back, back to you’, and finding a husband, ‘a model of you’. At this point the poem changes direction with the husband taking over the ‘Daddy’ role, exorcising the dominating father figure as epitomised by the vampire imagery. The resolution of her issues does not last, however. In “Lady Lazarus”, she obsesses over her suicide attempts and creates a division between herself and the men in her life, empowering herself with mythological, historical, and Biblical comparisons, ‘a sort of walking miracle’. She now accepts her isolation and sees it as powerful to be ‘the pure gold baby’, rather than a burden. This is culminated in the final stanza, where she compares herself to the solitary, majestic phoenix. This transformation also signifies the escape from the stereotypes and labels that have manipulated Plath’s identity throughout her life. Sylvia Plath’s isolation from her father grows from a simple childhood yearning for connection to the ultimate separation: death and rebirth. Each poet achieves a different response in their exploration of society and the self, but they are all unified by their isolation. The contrasting elements arise from the poet’s acceptance or hate of their isolation, achieved through the discourses and techniques utilised. The poems are consumed by the poet’s separation, allowing the reader to discover their own isolations. Nick Mitchell