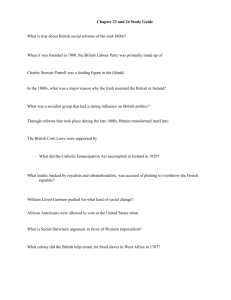

The Impact Of World War One On Britain

advertisement

What Limited British Foreign Policy After WW1? Britain had always run her Empire on limited means. It relied on its large navy and had much influence thanks to its Empire. It had maintained some independence in its action. After World War One Britain still felt that like before the war, they had a right to have a significant say in world affairs. However, there were many limits on Britain’s foreign policy which meant that she could not pursue such an independent policy as before. Economic Restrictions: Britain had been in economic decline before the war but this was accelerated by the conflict. Crucially Britain had run up huge debts in fighting the war, particularly with the USA. She had borrowed £959 million. As a result the national debt increased 11 fold and interest payment on loans represented 40% of annual government spending, as opposed to 12% in 1913. Britain could not expect to receive payments back for loans she had given to Russia (due to Communist takeover) and France (due to war damage). This would put severe limitations on Britain’s role in world affairs. E.g. PM Andrew Bonar Law in 1922 said; “…we cannot alone act as policeman of the world. The financial and social position of this country makes it impossible.” In addition Britain had had to liquidate many of its assets to pay for the war. Hard questions would have to be asked of Britain’s foreign, imperial and defence policies. A domestic economic slump from 1921 onwards also limited Britain’s ability to play an active role in world affairs. Unemployment increased in Britain’s staple industries such as coal, cotton, ship-building and engineering. This in turn reduced the demand for materials from the Empire to feed these industries. Pressure At Home: Lloyd-George’s coalition government (1916-22) had promised demobilising forces “homes fit for heroes.” Thus there was a pressure for social reform at home which would take up more of the government’s resources. How could Britain hope to follow an expansive foreign policy when she was committed at home? At home there was a growing unwillingness to shoulder the burden of greatness overseas. The cost of being the world’s policeman was too high in blood (900,000 dead + 2 million wounded) and money, as seen in WW1. Could Britain remain great on the cheap? Could someone else like the League of Nations help preserve the peace? Maintaining the Empire: Britain’s need to police and maintain the Empire remained after WW1 but on a much stricter budget. In fact the Empire was essentially enlarged with the addition of Iraq and Palestine as mandated territories that had formerly been part of the Ottoman (Turkish) Empire. The Empire was also not as united as before. Increasingly, the White Dominions (Canada, Australia and South Africa) where all keen to assert their independence. India too, after a massive contribution to the British war effort was becoming tired of white rule as shown in Amritsar Massacre in 1919. These demands would put more strains on Britain’s resources. Defence Cuts: Britain coped with all the above problems by cutting defence expenditure to balance the books. These cuts were justified by the Ten Year Rule established in 1919 in which Britain did not expect a war for at least ten years. In 1918 there were 3.5 million men in the armed forces but by 1920 this was reduced to 370,000. As a weakened military power she could not hope to follow an ambitious foreign policy. But these cutbacks and the unwillingness to give any European military commitments deeply increased French fears of Germany. Conclusion: These factors combined to force Britain into a rethink on its foreign policy aims and ambitions. Crucially it would be the impact economically of the war which would place limitations on British policy. These restrictions would obviously impact on the aims that Britain had for her policies overseas. So what were her aims? Perhaps some clues can be found from the following memorandum from the Foreign Office; “We have no territorial ambitions, nor desire for aggrandisement. We have got all that we want – perhaps more. Our sole object is to keep what we want and live in peace… so manifold and ubiquitous are British trade and finance that, whatever else may be the outcome of a disturbance of the peace, we shall be the losers.” As Pierce and Stewart comment; “Like some lady of advanced middle age who had over-exerted herself, Britain now wanted a cup of tea and a snooze.”