Portfolio Goals

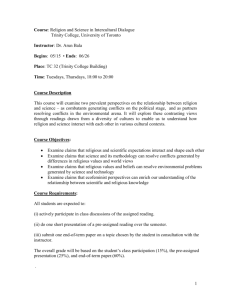

advertisement