Robbins Komine

advertisement

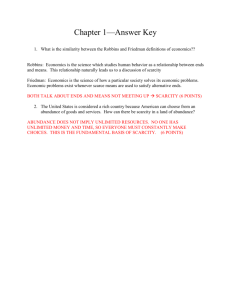

ESHET2009/GREECE THE COMPLEX ACCEPTANCE OF LIONEL ROBBINS IN JAPAN Atsushi Komine* Draft version (2.0), not to be quoted 5April.2009 1. INTRODUCTION Lionel Robbins is an outstanding figure in the history of economics, but a very few textbooks in the history of economic thought devote some lines to his contributions to economics, systematically confined only to An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science (Robbins 1932; 1935a). There are several reasons why this happened. The Essay, Robbins’s first book, generated a huge debate on the nature of economic science in the following years, not only among the most prominent economists but also among scholars of other disciplines, therefore becoming a reference writing in epistemology. But it has been an unfortunate success. Irrespective of the life-long attempts by Robbins to make himself properly understood (Robbins 1981), the Essay has been usually regarded as the manifesto of the epistemology of neoclassical economics, where its underlying ontology characterized by rational maximizing agents, social atomism and a positivistic approach to economics is systematized and laid down. And this happened when the orthodox theory seemed most incapable of explaining events and provide answers to the urges of the post 1929 recovery. For instance, in 1970 Robbins's Essay was still regarded as "a must read for studying the methodology of modern economics" (Kumagai & Ohishi eds 1970: 21)1. At the same time, Uzawa (1970) criticized his standpoint as "a biased view that emphasizes efficiency and ignores justice and equality"2. This simple view had been popular regardless of the pros and cons. However, when and how was this view prevailing? What was the first stage into introduction of his arguments? We naturally need to look at this chronologically. Recently, we have suggested (Komine 2007; Masini 2007b) that much of this criticism in Britain and the USA in fact depended not only on the wrong timing of Robbins’s books but also on a misunderstanding of his manifold messages. This paper aims at verifying whether such problems appeared also in other contexts. * Faculty of Economics, Ryukoku University, Japan (komine@econ.ryukoku.ac.jp). An earlier draft, which was jointly written with Fabio Masini (University of Roma Tre), was presented at the second Eshet-Jshet conference in Tokyo (Hitotsubashi University) on 22nd March 2009. All the translations from Japanese texts into English are ours. 1 The last (22nd) print date of translation of Essay was August 1981. At least for 34 years from 1957 to 1981, reprints were continuously available in Japan. Thanks are due to a publisher of Toyo Keizai Inc. and Professor Wakatabe (Waseda University) for providing me with the above information. Now the translation is out of print, but there is a plan to publish a new translation of Essay. 2 The two examples are from Hayasaka (1971: 46-48). 1 We shall make a historiographical review of the reception of his works in Japan, one culturally very different country, outside the Europe. Before the two world wars, Japan, along with Germany and Italy, was rapidly developing. Her modernization had started around the 1860s. In the 1930s - when the first books by Robbins were spread - and after WWII- when they were translated, Japanese intellectuals were eager to absorb new institutions and ideas, including the contributions from the “years of high theory”, while trying to keep their own tradition and culture. Even more important, Japan, along with Italy, has experienced long periods of political and cultural dictatorships which created a very special context that made the discussion and diffusion, acceptance or rejection of Robbins’s messages particularly difficult. As we shall point out, these peculiarities induced in some cases an underestimation, in others a misrepresentation of some of his main thoughts in the 1930s, which in some cases perpetuated in the next decades. We will look at the reviews devoted to Robbins’s works, their translations and the main debates on his contributions to economics in Japan, considering the most relevant time intervals, which are from the publication of the Essay until the 1950s in Japan. It is convenient to distinguish three phases in the introduction and dissemination of Robbins into Japanese academic circles: in the 1930s, the 1950s, and the 1980s and afterwards. Yet we will mainly focus on the first two phases. Before discussing the two in detail (Sections 3 and 4), we will begin by considering the academic situation, especially of economic journals, in Japan. We shall draw some concluding remarks in Section 5. 2. JOURNAL SITUATION IN JAPAN The Meiji Restoration (the start of modernization) occurred in 1868. Under the national slogan Fukoku Kyohei,“wealthy nation and strong army”, a social regime was also rapidly enriched. In the Taisho era (1912-1926) in particular, when movements were strengthened for freedom of speech, the franchise, the basic rights of labour and so on, academic circles including that of economics came to be formally organized. We will divide 50 years (1900-1950) into four stages. Each had different characteristics. 2-1. Early Noble Spirit (1900-1920) This period had the direct background of importing advanced literature. In 1896 the Society for the Study of Social Policy [Verein für Sozialpolitik] was founded as the one of oldest academic associations. Although it was open to wide topics and affiliations, numerous leading economists joined, such as Hajime Kawakami 2 (1879-1946) and Tokuzo Fukuda (1874-1930)3. The Society was very active in not only theory debates but also policy proposals like Factory Acts. Three journals must be considered. First, the Kokumin Keizai Zasshi, or Journal of Political Economy and Commercial Science, now Journal of Economics and Business Administration, was the oldest academic journal, exclusive to economics (and commerce). The journal was founded in 1906 in Kobe. However, two institutions jointly managed the editorial board: Kobe and Tokyo Higher Commercial Schools. Hyoye Ouchi (1888-1980), a leading Marxist, once said, "The journal was the birth cry of economics in Japan, and ... aimed to become the Japanese Economic Journal. In Japan, economics emerged from the basis of commerce and became the main stream" (cited in Sugihara 1980: 229). Second, Mita Gakkai Zasshi, whose English name is now Mita Journal of Economics, was founded in 1909 by Keio University. The journal was also one of the oldest for economists, although it initially featured a combination of four fields: letters, commerce and economics [rizai], law, and politics. Third, Keizai Ronso, or the Economic Review, was founded in 1915 by Kyoto Imperial University. Economists there had belonged to the faculty of law and held their journal to submit to, Houritsugaku Keizaigaku Naigai Ronsou. However, just before the faculty of economics separated in 1919, there had been a growing tendency to have an independent journal. This atmosphere led to "an unexampled great success as an academic journal" (ibid.: 231). As leading economists, even from other affiliations, wrote numerous articles on economics, the journal could be published monthly and sold many copies. The Economic Review of Kyoto University had "an exquisite balance between abstract studies and policy proposals" (ibid.: 232). In this period, academic economists could be gradually gathered in a faculty or an institution of economics and/or commerce. They had a newly noble spirit of independence from other fields and a thirst for advanced knowledge about economics. Therefore, the above three journals were monthly, and printed a great deal of information, (bibliography lists, short introduction and long book reviews), about the newest foreign articles and books. Japan was at the dawn of economic professionalization by the 1920s. 2-2. Introverted Establishment (1920-1945) Disordered conditions after World War I, or the beginning of the Showa era (1926-1989), drastically changed the academic situation, too: from Taisho Democracy to Showa militarism, and from a liberal economy to a controlled one. Marxism was suppressed and a number of professors were arrested and/or forced to resign. Thus, a mode of Gottl-Ottlilienfeld 4 , a route to Nazism, and purely 3 For a brief introduction, see Negishi (2001). According to his national-socio-political economics, economies were understood as ein Gebilde (a formation of economy). Here desire and satisfaction could be continuously harmonized by 'a right force'. Economies were not a relationship between commodities but human intentions. As 'a right force' could be anything, those in power and followers regarded Gottle-ottlilienfeld's style as convenient. 4 3 mathematical economics were the only study options in universities. This was the very time when Robbins was introduced in the 1930s. During or just before this period, the above journals changed their character: Mita Journal of Economics (Keio) became a bulletin of the faculty of economics alone in 1914; from 1919, when the faculty of economics had finally become independent, the Economic Review (Kyoto) became an organ of the faculty members, that is, a journal to which few outsiders contributed; and in 1925, after Tokyo Higher Commercial School was raised to university status (Tokyo University of Commerce) in 1920, Journal of Political Economy and Commercial Science (Tokyo and Kobe) came to be handled by the Kobe counterpart only. This means that the Tokyo counterpart had established its own organ in 1921, The Shogaku Kenkyu, or A Study on Commerce5. In short, the three journals purified themselves in two directions: economics (and commerce) only, and faculty members only. Tokyo Imperial University followed in the same line. In 1919, the faculty of economics became independent from that of law and founded the Keizaigaku Ronsyu, or the Journal of Economics, in 1922. The School of Political Science and Economics, Waseda University 6 , established its organ in 1925, The Waseda Journal of Political Science and Economics. One exception to the introverted trend was the Kyoto University Economic Review (KUER) by the faculty of economics. The journal was written entirely in English. According the preface of the first issue (July 1926): “the first half of the Meiji Era (the latter half of [the] 19th century) can be regarded as an age of translation. ... But during the second half (the beginning of [the] 20th century) they began to show a critical attitude towards the imported ideas and doctrines [...] but as the majority of them [scientific studies] were written in the Japanese language they have not been accessible to Western scholars. [...] such a condition is truly regrettable from the standpoint of intellectual cooperation.” (KUER, editorial committee 1926: ii). The academic level in economics moved to the second stage, from absorption to emission, from importation to exportation, or from imitation to creation. In fact, Lange (1935: 189) cited Kei Shibara's KUER paper of 1933 on Marx and the general equilibrium theory. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society always compiled KUER papers, for instance, Yasuma Takata's "A Power Theory of Wages" (December 1929)7. Economica recorded its received KUER in November 19268. Economica of 1927 welcomed this new attempt: 5 In 1932, the Keizaigaku Kenkyu, or A Study on Economics, was founded and separated from this journal. 6 Keio and Waseda are prominent private universities. Other universities in this paper are all national universities. 7 Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Vol. 93, No. 3, 1930, p. 480. 8 Economica, No.18, November 1926, p. 376. 4 This has been due to the extreme difficulty of the Japanese language, and it is to make accessible to the Western world the fruits of Japanese economic scholarship that the Kyoto University Economic Review, printed in English, has been founded. [...] This new project deserves special sympathy because the editors and contributors of the Review work in a country where heresy-hunting by police and politicians is all too common, and from which dispassionate students of the social sciences are not exempt9. We will later, in 3-2, show five examples as to how Robbins was introduced during this period. 2-3. Bamboo Shoot (1945-1950) The War ended in August 1945. Ultra-nationalism and Militarism were swept away by the occupation forces. Academic freedom was gradually established. In wartime, economics was the most severely oppressed among the social sciences. As a reaction, promoting liberal research activities resulted in a boom in the foundation of new journals. Economists subscribing to the journals had "an awareness of the issues regarding how they should absorb and digest theoretical achievements of the 1930s in Britain and America" (Sugihara 1987: 139). There are two features. First, these journals were "inter-college": that is, unlike previous ones, their publishers were outside of universities; their editorial boards and contributors came from a variety of affiliations. Second, the trail failed very shortly. Almost all of new emerging journals were discontinued by 1950. As far as our investigation is concerned, there were no articles on Robbins during the period. 2-4. Stabilization, or Reduced Reproduction? (1945-present) By 1950 an academic environment10 came to be reestablished in two directions. First, influential scientific societies were substantially founded or reorganized: the Japanese Economic Association, originally founded in 1934, was split into the Theoretical Economic Association (1949) and The Japanese Econometric Association (1950)11. In 1950 the Japanese Society of the History of Economic Thought was founded 12 . Open networks were available. Second, universities reorganized their own organ, in accordance with a drastic university system reform in 1949. Keizai Kenkyu, or Economic Review (1950- present) by the Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University, was a symbol of a hope to establish a new economic discourse. Other faculty periodicals for economists were also reorganized. Each faculty established its own journal, bulletin, or house organ 9 Book Reviews and Shorter Notices, Economica, No.19, March, 1927, p. 129. The number of universities (four-year course) in 1950 was 201 (national: 70, local: 26, private: 105), while that of 2007 was 726. See MEXT, School Basic Survey, 2007. http://www.mext.go.jp/b_menu/toukei/001/08010901/index. htm (7 December 2008). 11 The two were reunited in 1968. Now the association, including over 3000 members, restored the original name in 1997. 12 Having around 750 members, the Society is the largest on a single country basis. 10 5 (Bronfenbrenner 1956: 395): contributors and editorial board members were in most cases confined to its faculty members. Sugihara (1980: 241) lamented his conclusion that "economic journals in Japan could not be representative, nationwide or first-class media in the end". Professional economists in Japan had long been subject to this characteristic, except in a few cases such as International Economic Review (IER) by Institute of Social and Economic Research, Osaka University and the University of Pennsylvania13, The Japanese Economic Review, or previously the Economic Studies Quarterly (1950-1994) and Economic Review (in Japanese, Hitotsubashi University). 3. EARLIER RESPONSES DURING THE 1930S Essay was published June 1932. Except a short review by The Times Literary Supplement 14 , Edwin Cannan first reviewed the book in September in the Economic Journal. "For professional economists in Japan, it has been essential to check not only monographs but also articles in academic journals" (cited in Ikeo 2006: 12). Thus naturally, the notice of the publication could quickly reach Japan. It was formally recorded in a Japanese journal (probably) for the first time in Mita Journal of Economics in November 193215. In this section, we explain five cases which indicate how Japanese scholars reacted or responded to Robbins's books. However, we begin by introducing a Japanese who had claimed a similar position to Robbins in the late 1920s, 3-0. Ohkuma Robbins reassessed P. H. Wicksteed (1844-1927), by editing a reprint of An Essay of the Co-ordination of the Laws of Distribution (1932/1894). Robbins found out a principle of rational beheviour in Wicksteed to penetrate economic phenomena as a whole. Similarly, Nobuyuki Ohkuma (1893-1977) in the 1920s claimed to discover a basic principle of economy. Okuma, a pupil of Tokuzo Fukuda (1874-1930), attended Robbins's lectures in the Michaelmas term of 1929 at the LSE (Okuma 1977: 239). Just as he reached London in 1929, he finished writing a famous book, A Tale of Robinson Crusoe in Marx. Ohkuma insisted that even Marx, referring to Robinson Crusoe's way of life, implicitly assumed "the Allocation Principle". Crusoe had to solve the problem of allocation when he decided an optimal division of his labour hours. Marx said this type of allocation included an essence of value (Ohkuma 1929: 12-13). Pointing out this episode, Ohkuma concluded that there is a unified theory to be shared both in the labour theory of value and in the theory of marginal utility. That is the Allocation Principle. In other words, the law of equi-marginal utilities penetrated even Marxian theory. Economic phenomena should and could be understood as 13 IER was inaugurated in 1960 by Michio Morishima (later LSE) and Lawrence Klein. The Times, 16 June 1932. 15 Mita Journal of Economics, 26(11), November 1932, p.120. 14 6 individual rational behaviour to select means under given productive resources to satisfy his/her own wants. Rediscovering and naming the Principle, he tried to integrate all doctrines in economics. Ohkuma's way of thinking was very similar to that of Robbins16, at least to a great extent. Robbins shifted his emphasis regarding the essence of economy from objective materials to subjective behaviour. We do not insist either that Ohkuma influenced Robbins or Robbins had an impact on Ohkuma. However, around 1930 there was definitely a coincident concern between them as to rational behaviour, which constructed an economy as a whole. 3-1. Yasui Takuma Yasui (1909-1995) was one of the most eminent mathematical economists from the 1930s and onwards in Japan. The climax of his contribution to economics was to study the stability condition of equilibrium in the 1940s17. He was initially influenced by Alfred Amonn (1883-1962), visiting professor of the University of Tokyo from 1926 to 1929, and J. A. Schumpeter. The former gave lectures based on Cassel. When the latter visited Tokyo in 1931, Yasui asked him how best to start a postgraduate study of economics. The answer was "Begin with Walras" (quoted in Ikeo 1993: 195). At that time, academic economists in Japan tended to adhere to the German historical/philosophical school and Marshallian type. Thus Yasui, who read the latest European journals every month and studied the Lausanne School in detail, was a very rare case. Yasui wrote a detailed but introductory book review of Essay in June 1933. Definitely, this was the first response in Japan. He said, "If we define methodology as to extract and examine logical structures of an empirical science, German academic have monopolized it as well as philosophy in general" (Yasui 1933: 124). According to Yasui, Britain was, in contrast, too practical. Just remember an old book of J. N. Keynes, and Marshall's too easygoing definition of economics. Thus, Robbins's Essay was itself a surprise and an object to be given attention due to its 'scarcity'. Robbins's position was to form the foundation of economic theory by the marginal utility doctrine (ibid.: 125). Afterwards, Yasui summarized 6 chapters without any comments, except one: "Robbins distinguished economic theory from economic history. The former is related to formal implications between means and ends. The latter is associated with substantial instances of the relationship. He then explained the materialistic view of history. However, we omit it because his understanding was too poor; he confused production power with technology" (ibid.: 128). In general, Yasui was also so familiar with German literature18 that he 16 Ohkuma (1929: 278) regarded a principle of scarcity as inferior to that of allocation. As the latter included the theory of equilibrium, it was a more comprehensive idea. See Makino (2006) for a detailed account of his contribution to economics during and after WWII. 17 For a concise explanation, see Negishi (2002). 18 On the other hand, Yasui (1980: 52) pointed out that Essay had a fault: it was too Austrian as a whole. 7 seemed slightly to despise the British methodology of economics including Robbins. However, when he conversed with Robbins in Tokyo in 1973, he said, "I remember that I was strongly impressed with your Essay. Therefore, you were my master in a sense. I became much interested in the London School of the early 1930s" (Yasui 1980: 212). The book was very influential for him in that "why Robbins's Essay is important is due to the main theme of the book; the fundamental question of economics lay in rational allocations of resources19" (Yasui 1980: 52). Yasui had searched for a skeletal structure in economies. His hero was Walras. Thus, he found the message from Essay that rationality in choice was essential. 3-2. Nakayama Ichiro Nakayama (1898-1980), a successor of Fukuda and once the president of Hitotsubashi University in Tokyo, was one of the greatest economists in Japan, who was active in theory and practice from the 1930s to the 1970s20. He studied under J. A. Schumpeter in Bonn in 1927 and 1928. Whilst Fukuda, Hajime Kawakami (1879-1946) and Sakuzo Yoshino (1878-1933) are among the first generation in economics, or more precisely, social sciences in Japan, Nakayama is the representative of the second one who influenced numerous economists and policy makers, especially in the reconstruction periods after WWII. Nakayama touched on Robbins's Essay in his book, Junsui Keizaigaku, or Pure Economics (1933). This reference was the earliest response in Japan. As the book was described even in one fierce critical review as "the best book which won both praise from economists and a welcome from general readers" (cited in Nakayama 1958: 1035), numerous economists must have recognized Robbins through Nakayama's book. He referred to Essay in the context of how the theory of equilibrium made sense in economics in general (Nakayama 1933: 18, note 5). Since he did not specify the pages he had consulted, we conjecture his intention with the help of his later words in an introduction to the Japanese translation of Essay (1957). "Robbins and Schumpeter shared completely the same view that methodology did not precede its theoretical content itself. ... However, Robbins's Essay is more substantial than Schumpeter's Wesen. ... [While Schumpeter had] both the statics and the dynamics. Robbins differed from this way. The principle of scarcity was the kernel of theories. There was no essential distinction between the theories of statics and dynamics in principle. ... This single theoretical weapon would make us grasp the essence of complex and fluctuating economic phenomena." (Nakayama 1957: iii-iv) 19 Therefore, Yasui regarded Robbins's critique of Pigou (interpersonal comparison of utility) as secondary. See Yasui (1980: 52). 20 For a whole evaluation of his works, see Minoguchi et al. (2000) and Ikema et al. ed. (2000: 172175). 8 Accordingly, Nakayama must have sympathized with Robbins in two ways: first, the theory of equilibrium should be a means of understanding the substance of human behaviour in economies; second, by emphasizing scarcity, theories of statics and dynamics should be continuous, a kind of monism. Nakayama (1933) did not introduce the whole arguments of Essay, such as the subject matter of economics, its ends and means, the principles of economics, theory and practice and so on. Rather, he felt sympathy towards the way Robbins developed his arguments by using a concept of scarcity in order to grasp the nature of economies through focusing on human behaviour. His book was so popular21 that it could be a good guide to Robbins's methodological arguments for other economists in Japan, but simply Nakayama needed Essay to develop internally his own economics. In fact, his ultimate end was to explicate human behaviour at the micro level and stability and progress at the macro. 3-3. Neil Skene Smith Neil Skene Smith (1901-?) is a neglected economist, but in a sense played an important role in the introduction of British information into Japan and vice versa. He owed his academic career to Professor A. J. Sargent (1871-1947) and Dr Hugh Dalton (1887-1962) (Skene Smith 1929: vi), both LSE members. The former taught economic history, the latter economics. He inherited his ability from the teachers: later he published a book on the economic history of Tokugawa Japan, and he could also introduce recent economic theories of the 1930s. After being an assistant in the department of commerce at the LSE, he became a 'part-time foreign lecturer' of Tokyo University of Commerce from 1932 to 1937. There he taught commerce, trading business, English and Western economic situations22. An important article (in English) was published in the Journal of Economics (University of Tokyo) in March 1934. The title was "British Economic Theory during the Last Four Years", written on 7th February. Skene Smith introduced striking changes among Cambridge and London economists. Both schools were "strongholds of Welfare Economics" (Skene Smith 1934: 75). Recent controversies were on monetary theories and the relationship between savings and investment, between Keynes and Robertson, or Hayek. Keynes' Treatise on Money (1930) and Hayek's reply in particular were introduced in detail. He also briefly referred to academic contributions of Pigou, Harrod, Kahn, the Robinsons, E. F. M. Durbin and Sraffa. Then, he said, "London in spite of this increasing degree of homogeneity is still heterogeneous" (ibid.: 76): he pointed out the variety of economic doctrines at the LSE, such as Cannan, Gregory, Dalton, Barrett Whale, H. E. Batson and Beveridge, as well as close outsiders like J. A. Hobson and Hawtrey. However, he admitted the existence of a new stream of economics by Robbins and Hicks, together with Hayek. "In London, Robbins has been largely 21 In 1942, the book had its fourteenth impression. See Handbook of Tokyo University of Commerce, Annual, 1930-1940. I am indebted for this information to librarians in Hitotsubashi University. 22 9 responsible for the change of outlook" (ibid.: 93). In his Essay, he rejected material welfare as the subject-matter of economic study. He replaced that with human behaviour as a relationship between ends and scarce means which have alternative uses. Skene Smith regarded this method of approach as "very healthy" (ibid.: 94) and interpreted that Robbins re-stated the nature and significance of economic science, creating "the London School" (ibid.: 95). At the same time as he sensed the new powerful stream by Robbins, he also longed for the heterogeneous London School, because it was a bad day for British economic thought if one group became definitely established as supreme (ibid.: 95). Although no evidence has been found yet that Japanese scholars even referred to Skene Smith's review article, it must have influenced them. For the Journal of Economics was influential and his content as a LSE insider was very vivid in detail. Therefore, along with Keynes versus Hayek, Robbins's Essay must have been recognized as an important study among academic circles in Japan. 3-4. Kiga Kenzo Kiga (1908-2002), the third son of Kanjuu Kiga (1873-1944), was a thorough liberalist of Keio University. His father Kanjuu, also a Keio Professor, was one of the early founders of Keio economics 23 and introduced the German historical school into Japan. When he studied in Germany before WWII, Kenzo was fascinated by L. Mises (Kiga 2000: 11). After studying Hayek and L. T. Hobhouse, he established his philosophical position: anti-Marxism and democratic socialism (Kato 2002: 23). Thus he regarded Robbins's Economic Planning and International Order (1937) as "a typical orthodox British economics because it was full of thorough claims of liberalism" (Kiga 1937: 131). Robbins refuted economic planning in defence of liberalism. After summarizing the content, Kiga pose a question: "how international liberalism, which Robbins proposed, could resist the general tendency (a bloc economy) of the times, whereas he understood it could contribute to world peace and happiness" (ibid.: 135). In other words, Robbins could not explain how international liberalism could be certain to avoid war. Kiga concluded that "although Robbins's idea was a utopia, his commentary on types of economic structure was tremendously useful" (ibid.: 136). At that time, numerous economists in Japan were forced to consider a war economic system or a controlled economy. In contrast, Kiga carried out his original intention: orthodox liberalism. Thus, he read the book as one fighting for classical liberalism. However, he overlooked the fact that Robbins went far beyond it: when Robbins said that "without order, no economy: without peace, no welfare" and "there is world economy. But there is no world polity" (Robbins 1937: 238-239), 23 Ukichi Fukuzawa (1835-1901), the founder of Keio University, is the most famous enlightenment thinker in modern Japan. Having a hatred for feudalism, he introduced numerous European ideas, systems and institutions. Keio economics is based on Fukuzawa's liberalism, and was best embodied by Shinzo Koizumi (1888-1966), a pupil of Fukuda and a thoroughly liberalist. 10 he admitted artificial intervention in order to make the international economy work well. Kiga, a translator of Hayek 24 , would not recognize Robbins's modified liberalism. 3-5. Nomura Kanetaro Nomura (1896-1960), Professor of Keio University, studied under J. H. Clapham in Cambridge around 1923 and made a special study of British and Japanese economic history. Later his interest also pointed to the history of the Japanese economic thought. He raised the academic level of economic history in Japan from translation and/or introduction to independent empirical research. As far as our investigation is concerned25, Nomura (1939) had the widest scope as a reviewer on the methodology of economics in British controversies. In the light of his concern about a relationship between scientific theory and realistic practice in economics, he introduced nine authors other than Robbins: R. W. Souter, F. Knight, L. M. Fraser, B. Wootton, E. E. M. Durbin, R. F. Harrod, A. C. Pigou, Surányi-Unger, and W. H. Beveridge. "Robbins's Essays (1932) provoked an animated controversy on the nature of economics in British and American academic circles" (Nomura 1939: 3). "Recent academic chaos 26 resulted from disagreement, among economists, on how theory should be applied to practice" (ibid.: 5). Telling A-type economics (touching wealth and welfare) from B-type (touching scarcity), he introduced the controversy among the ten persons above. While he agreed with Robbins's attempt to make economics more scientific 27 , Nomura opposed Robbins's definition of economics because he thought that economic behavior was historical and collective (ibid.: 29). His ideal process for good economics is firstly, the establishment of its scientific nature, secondly the creation of rich theories, and thirdly the possible indirect application of them to practical matters (ibid.: 31). On the one hand, Nomura agreed with Robbins's attempt to make economics a science. A science should be more objective, positive, and universal (ibid.: 28), On the other hand, he questioned the economic science Robbins proposed because as a historian Nomura opposed Robbins's recognition that economic history should also be studied in the light of the relationship between ends and scarce means. For 24 His father translated Adam Smith. In 1935, he and his father translated Iving Fisher. Later from 1953 to 1955, he translated Pigou 's Wealth and Welfare. 25 We have completely checked 6 major economic journals through 1931-1939: University of Tokyo (The Journal of Economics, 1922-); Kyoto University (The Economic Review, 1915-); Hitotsubashi University [then, Tokyo University of Commerce] (Hitotsubashi Review, 1938-2006); Kobe University (Journal of Political Economy and Commercial Science, 1909[1925]-); Osaka City University [then, Osaka University of Commerce] (Journal of Economics, 1937-); and Keio University (Mita Journal of Economics, 1909[1914]-). 26 Nomura attributed it to a drastic change of social organizations on which previous economics relied when creating its theoretical basis (ibid.: 26). 27 At the same time, he didn't overlook Robbins's real intention that there was a wider economics (applied economics) beyond economic science that economists should take seriously when considering policy-making (ibid.: 15). 11 Nomura, economic history was part of history, and history was synthetic phenomena including economic, political, social, religious, and military elements which were inseparable (ibid.: 32). 4. DECISIVE RESPONSES IN AND AFTER THE 1950S Research was inactive in social science during the 1940s. State-controlled economy, such as Gottl-Ottlilienfeld's, was almost all one was allowed to study. After great disturbances even in the academic world, the chaos ended in the 1950s. Just before and after the translation of Essay appeared in 1957, Robbins's arguments were vigorously discussed. We will discuss three types: original, popular, and the translator's arguments. 4-1. Tomita Shigeo Tomita (1925-) was Professor of Keio University, having studied mainly the methodology of economics. Tomita, a pupil of Yoshindo Chigusa (1911-2000), was deeply influenced by Kitaro Nishida (1870-1945), the greatest philosopher in modern Japan. He wrote a paper in 1950 entitled "Some Differences in a Mode of Thinking between Materialist Definition and Scarcity Definition". Tomita took up Robbins's arguments in the light of the epistemology of science in general (Tomita 1950: 24). As such, his paper was full of metaphysical reflections on perception. If economics was concerned with materials as Cannan, Marshall, Pareto, J. B. Clark among others had defined it, things were strictly divided into materials and non-materials. A thing had, by nature, an isolated, abstract and absolute existence. A man had nothing to do with a thing, regardless of materials or non-materials. A man was entirely an outsider who coolly observed a subject (ibid.: 30). In contrast, if economics was related to human behaviour between scarce means and ends, a thing could be economical or non-economical according to an actor' s perception. Any area in the world could be an economic matter. A thing had a connected, concrete and relative existence. A man could control a thing in any way he chose. A man was, in a sense, an insider who both observed closely and introspected himself (ibid.: 34). Thus, according to Tomita's conclusion, Robbins's argument was epoch-making in that his scarcity definition included an image of human beings who had infinite possibilities as "a predicate existence" (ibid.: 38). Tomita also pointed out one defect in Robbins's Essay: his understanding of society. Robbins's society was based on a simple aggregation of individuals. Tomita preferred an organism in historical schools, or Nishida's "principle of the individual". He recognized another principle of an individual in society was necessary (ibid.: 35). Tomita consciously used Aristotle's terminology, such as substratum and predicate & subject. Although Aristotle regarded a subject [hē prōtē ousia, the primary substance], which corresponded to materialist definition, as substratum, Tomita considered a predicate [hē deutera ousia, the secondary substance], thus scarcity definition, as more important in accordance with Nishida's reversed 12 arguments28. Tomita ranked Robbins highly because he found in Essay a potential development of epistemology. 4-2. Baba Keinosuke Baba 29 (1908-1988), Professor of Hitotsubashi University, was interested in the dynamic process of each era and place in industrial society. His target was to investigate both a fundamental economic philosophy and the future of industrial society. Thus, in the 1950s he wrote textbooks on the methodology of economics and on the history of economic thought. In the preface, unlike Tomita, Baba declared that he did not consider a methodology of science in general, due to a circuitous path (Baba 1956: i). Tasks of the methodology of economics were not only to examine methods in economics but also to check its relevance to the relationship between theory and reality (ibid.: 4). It was important to grasp the modus operandi of economic phenomena. Even in numerous economic theories, there existed three methodological elements in common: (1) how to confine the scope of economic problems; (2) how to analyze the economic behaviour of human beings; and (3) how to analyze economic structures in society. Concerning the first element, Baba denied Robbins's dichotomy between materialist and scarcity definitions (ibid.: 5). Baba regarded the former as a view from objective wealth, whereas the latter was subjective behaviour. He pointed out that scarcity was not absolutely but relatively, and needed monetary calculations, whilst materials meant things measured by money. He concluded that both definitions were not exclusive but complementary. Baba advocated a new definition; "economy is phenomena of the relationship between means and ends by way of money in order to promote material welfare" (ibid.: 6). Baba denied Robbins's originality in methodology. He did not care about his attack on Pigou's welfare economics. Instead, he tried to synthesize both standpoints. This may be possible because he thought both micro and macro points indispensable to understand economic phenomena, and he believed every economist could share the same ideal of the promotion of welfare in any way. 4-3. Tsuji Rokubei Tsuji (1916-?) was Associate Professor of Nagoya University (the faculty of liberal arts) and a pupil of Nakayama 30 . As he was interested in the methodology of non-Marxian economics such as Hicks, Nakayama seemed to select him as the translator of Essay. In fact, he supervised his translation. One year 28 Nishida concluded "pure experience" was a situation where a subject and an object were undifferentiated. 29 He was a pupil of Tokuryu Yamauchi (1890-1982) whose teacher was Kitaro Nishida. 30 Although we have investigated his life, little is known. He seems to have published only three papers on methodology (of Hicks and Robbins). Thanks are due to the following people for helpful suggestions: Emeritus Professor Toshio Yamada (Nagoya University), Emeritus Professor Kaneo Ando (Nagoya City University), and Dr Nanako Fujita (Nagoya City University). 13 after the publication 31 , Tsuji contributed his paper on Essay to a special book, Shinohara ed. (1958), to celebrate Nakayama's 60th birthday. Tsuji's style was not to evaluate Robbins's arguments as a whole, but to add only two comments on the main theme of economics and the practical significance of economics (Tsuji 1958: 134). On the one hand, Robbins was too strongly influenced by Austrians. They understood economies merely by way of utility. Consumers' Sovereignty, a priority of consumers over producers, was prevailing in Robbins's arguments (ibid.: 141). This attitude was wrong in two dimensions: firstly, the theory of general equilibrium, more elegant, did not assume the priority of consumers as well as producers. Secondly, there was an inconsistency between Robbins's declaration of neutrality and his emphasis on Consumers' Sovereignty. On the other hand, Robbins too strictly distinguished positive and normative sciences. Although he approved of this distinction (ibid.: 162), Tsuji insisted that economists should study positive science and philosophy of value judgments at the same time. Economics should be a proper guide to economic policies. They had to have broader knowledge such as politics, sociology, ethics and philosophy as well as pure and applied economics (ibid.: 164). Tsuji assumed a critical attitude to Essay, to some extent. Thus his last sentence, only this one originally in English, in the above paper was: "It is too Austrian and too positivistic and these distinctive features are incompatible!" (ibid.: 166). 4-4. Suenaga Takasuke Suenaga(1918-2004)learned under Hitotsubashi teachers, such as Kinnosuke Otsuka (1892-1977) 32 , Zenya Takashima (1904-1990) and Eiichi Sugimoto (1901-1952). He was particularly influenced by Sugimoto. He was once the president of Osaka University of Commerce. Suenaga (1950) reviewed Robbins's Great Depression (1933) in order to investigate how non-Marxian economics, in particular the theory of equilibrium, dealt with the crisis of capitalism. He regarded Robbins's analysis as, basically, a monetary theory of the trade cycle (Suenaga 1950: 16), and his remedy for the great depression as removing all rigid factors, such as wage and income policies, tariffs, and inappropriate state intervention (ibid., : 27). Non-Marxists were divided into two groups: one was Keynesians who approved of state monopolistic capitalism; the other neo-classical who intended to take economic conditions back to pre-WWI liberalism (ibid., : 32). Keynesians had British nationalism, whereas neo-classical seemed to be universal. However, there were some in Britain who earned a profit from Robbins's seemingly neutral arguments. Those were rentier and monetary capital. Suenaga concluded that Robbins's view was to a great extent 31 This is the first and only translation of Essay into Japanese. In 1933 Otsuka was arrested for violating the Peace Preservation Law and was unemployed for 13 years. He was a pupil of Fukuda, who demanded him that he translated Marshall's Principle. 32 14 conservative and his economics, the theory of equilibrium, pretended to be neutral yet had implicit value judgments. Suenaga was a good critic of non-Marxian economics, based on the history of economic thought. He wanted to show that Robbins's economics was not free from value judgment. 4-5. Sugimoto Eiichi Sugimoto, a pupil of Fukuda, was essentially a Marxian, but had a thorough knowledge of other schools such as the Lausanne, the Austrian, and the Cambridge Schools. After years of oppression before and during WWII, he began to prevail upon students to notice the importance of studying the history of economic thought and econometrics. He published very popular books, such as Explications of Modern Economics (1950) and A History of Modern Economics (1953). In these books, Sugimoto characterized Robbins, or to be exact, the London School including Hayek and Hicks, as a mixture of explicit elements from the Lausanne and the Austrian Schools. On the one hand, as economies Robbins described were based on the mechanical equilibrium relationship between prices, its methodology was Max Weber's "Wertfreiheit" (Sugimoto 1950: 153-156). On the other hand, Robbins's economics was simply individualistic and lacked social considerations (ibid.: 208). Sugimoto criticized Robbins's dichotomy between wealth and equilibrium, not scarcity, definitions (ibid.: 157) 33. Sugimoto's assessment of Robbins was so influential that it led to two attitudes: first, Marxian economists tended to criticize Robbins as a typical bourgeois economics, which demanded that economists should not think about value judgments (ibid.: 156); second, non-Marxian economists were apt to follow Robbins unquestioningly, by judging that his methodology was the only way to make economics more scientific. 4-6. Others Here, we discuss one article, four books and other translations. Keizo Kashiwara wrote a paper of 69 pages, which is identified as merely a summary of the whole content of Essay. Except for the introduction of the paper, there were not even any comments on any page. This way of introducing foreign literature was not rare in those days. In the introduction, he called Robbins "the leader of the London School" (Kashiwara 1953: 1). He also referred to two Japanese textbooks on the history of economic thought which reviewed Essay: Deguchi ed. (1953) and Sugimoto (1953). Kashiwara found his interest in realistic aspects of Robbins's methodology unlike other German counterparts (ibid.: 2). 33 In contrast, Sugimoto thought highly of the Marshallian approach, which included a variety of equilibrium concepts from temporary to long-term. In short, dynamic processes were important, whereas the Walrasian market was timeless. 15 Deguchi ed. (1953)34 and Sugimoto (1953) were popular textbooks and very similar. They concluded that Robbins was similar to Mises and Hayek. According to their statement, the London School pretended to have characteristics such as being free of value judgment, positive, and technical economics. However, the School fought in defence of old liberalism (Deguchi ed. 1953: 420), as was typical in The Great Depression (1934). The Cambridge School was in contrast practical and embraced the empiricism of welfare economics. It was still rare even to refer to Robbins's Essay, while German methodology was the main stream. For instance, Keio (1933) and Takata (1949) did not mention the name of Robbins at all. Translations were making steady progress in the 1950s and the 1960s. Ministry of Defense (1957) translated The Economic Problem in Peace and War (1947). Curiously, there is the stamp of 'confident' on the copy of the translation, which survives only in the library of the University of Tokyo35. The Bank of Japan (1958) translated Robbins's paper entitled "Thoughts on the Crisis" in Lloyds Bank Review in 1958. After 1964, two books and two articles were translated into Japanese: The Theory of Economic Policy in English Classical Political Economy (1952/1964); The Theory of Economic Development in the History of Economic Thought (1966/1968); " Capitalism, Market Socialism, and Central Planning" (1963/1966); and "Bretton Woods Regime Did Not Handle with Inflation [not original title]" (Special Lecture) (1973/1973). From defence matters to monetary policy, history of economic thought, Robbins's arguments were still fascinating for Japanese readers. 5. CONCLUDING REMARKS We have surveyed the reception of Lionel Robbins in Japan in order to understand whether his messages were properly understood and at what extent they were known and diffused. We will now try to recall the main features of Robbins’s reception. In Japan, the characteristics of each period can be summed up as follows. Note that those concerned were mostly from Hitotsubashi and Keio Universities, except a few people from Tokyo and Kyoto Universities. For Fukuda and his eminent pupil Nakayama played a central role to absorb a mixture of methodology, led by German literature, and the general equilibrium theory. In the 1930s, they absorbed Robbins's arguments on their own initiative. In other words, they had already had initial intentions or viewpoints regarding economics and economies. Therefore they at times sympathized with, at other times criticized Robbins's economics exceedingly selectively. Yasui found Walrasian rational choice in Essay. Nakayama picked out a single theoretical weapon from Essay, scarcity, which was essential beyond statics and dynamics. Kiga (mis)understood Robbins's International Order as classical liberalism and approved of it, with noticing its unreality. The historian Nomura, who was 34 35 In fact, the part on modern economics was written by Suenaga. There are no other copies in Japanese universities and academic institutions. 16 interested in the relationship between theory and practice, paid attention to the British controversies on the methodology Robbins provoked. All needed Robbins to strengthen and develop their own views. Ohkuma independently discovered "the Principle of Allocation". We have to remember that these distinguished scholars could obtain recent information through economic journals abroad and interchange between personnel like Amon and Skene Smith, the latter was purely an introducer and a connector between British and Japanese academics. Besides, there were several leading bulletins published by each university in Japan, which could transport intelligence (their own papers) and information (newly-arrived books and articles). In the 1950s, just before and after the translation of Essay appeared, Robbins was again introduced into Japan. Although there were still original ways of absorption, such as Tomita (Aristotle and Nishida philosophy), Baba (eclecticism) and translations from a broader viewpoint, the main stream was created by Sugimoto and Suenaga. According to their standpoint, we name it Sugimoto-These, Robbins completed the exile of value judgments from economics, whereas he himself held a biased view of conservatism and old liberalism. This These has survived for a long time, as a standard image of Robbins. It is an irony of history. For, with a serene mind, Sugimoto strongly intended to create competitive research of Marxian and non-Marxian economics, by reconsidering the history of economic thought. However, his textbooks brought a simple evaluation of Robbins. One of the reasons for this simple handling is the ideological situation at that time. The academic world in economics was sharply divided into three: Marxists, neoclassicals, and Keynesians. Every camp competed for its scientific degree. Thus, simple Robbins was demanded for both Marxists and neoclassicals, where the former criticized, the latter accepted it. This gap did not come into the open because Keynesians dominated at that time. Thus, after the 1950s, there was almost no literature on Robbins which was worth citing for three decades. This slack academic situation was finally broken in the 1980s 36 and afterwards 37 , by Nei (1989), Kimura (2004), Matsushima (2005), and Komine (2007). In the light of history, as we have perused the original documents, particularly of the 1930s, it is clear that our precursors apprehended the diversity of what Robbins really meant, from the ontology and methodology, concrete monetary and currency policies, to federalism. It depends upon us whether their bequests are dead or alive. It is high time to re-examine a more general perspective of Robbins. Thanks to the rich arguments which accompanied Robbins’s reception in and after the 1930s, we can start to re-assess him by contemplating them critically. 36 The earlier exception was Hayasaka (1971), which denied the Sugimoto These and criticized Uzawa, a leading economist, who took it for granted and attacked it. An evaluation in Hayasaka (1971) was based on numerous original texts, both in English and Japanese. 37 The last reprint date of Essay was 1981. It is very ironic that a reprint has not been available in time of starting a reassessment after the 1980s. 17 References38 [Anonymous] (1934) "Supplement to Professor S. Smith's Article which appeared in the last Number of this Journal", The Journal of Economics, The society of economics, University of Tokyo. 4(4), April1934, 1-3. [Anonymous] (1948) "Trakhtenberg's Critic on Economics of Hayek and Robbins: A Bourgeois Economics which opposes to State Intervention", Sekai Keizai, or Journal of World Economy, 3(10), November 1948, 45-51. <48> Akamatsu, Kaname (1958) "The Structural Fluctuations in the world economies: Dr Nakayama' Stability and Progress", in Shinohara ed. (1958), 849-865. <1> Baba, Keinosuke (1956) The Methodology of Economics: A Form of Society and Economic Theory, Tokyo: Shunjusha Publishing Company. <40> Bronfenbrenner, M. "The State of Japanese Economics", American Economic Review, Vol. 46, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-eighth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, May, 1956, pp. 389-398. Committee of the Academic History of Hitotsubashi University ed. (1985) Academic Traditions of Hitotsubashi, volume 1, Tokyo: Hitotsubashi University. <42> Deguchi, Yuzo ed. (1953) A History of Economic Thought, Kyoto: Minerva Publishing CO., Ltd. <27> Hawtrey, Ralph G. (1926), The Economic Problem, London, Longmans Green. Hayasaka, Tadashi (1971) "Modern Economics and Lionel Robbins", Keizai Seminar (Nippon-Hyoron-sha Co., Ltd), 192, September 1971, 46-52. <39> Hitotsubashi University ed. (1995) The 120th Anniversary of Hitotsubashi University, Tokyo: Hitotsubashi University. <41> Ikema, Makoto, Yoshio Inoue, Tamotsu Nishizawa and Susumu Yamauchi eds. (2000) Hitotsubashi University 1875-2000: A Hundred and Twenty-Five Years of Higher Education in Japan, London: Macmillan Press Ltd. Ikeo, Aiko (1993) "Japanese Modern Economics, 1930-1945", in Themes on Economic Discourse, Method, Money and Trade, Perspectives on the History of Economic Thought Volume IX, edited by Robert F. Hebert, Aldershot; UK: Edward Elgar, 192-202. Ikeo, Aiko, ed. (2000) Japanese Economics and Economists since 1945, London: Routledge. <2> Ikeo, Aiko (2006) Economics in Japan: The Internationalization of Economics in the Twentieth Century, Nagoya: The University of Nagoya Press. <3> Ikeo, Aiko (2008) Kaname Akamatsu: Surmount My Economics, Tokyo: Nihon Keizai Hyoronsha Co. <4> Kashiwara, Keizo (1953&1954) "Lionel Robbins and the Methodology of Economics", part 1 & 2, The Review of Kumamoto Junior College, 8 & 9, November 1953 & March 1954, 1-33 & 1-36. <8> Kato, Hiroshi (2002) "Obituary: Kenzo Kiga", Reformer [previously A Study on Democratic Socialism], 43(5), May 2002, 23. <9> Keio ed. (1933) The Methodology of Economics, Tokyo: Okura Shoten. <15> Keynes, John N. (1890), The Scope and Method of Political Economy, London, Macmillan; II ed. 1897. 38 The Japanese literature in Japanese has been translated into English and listed within the general references according to the western alphabetical order. At the end of each reference there is a <number> referring to the ordering of the attached original-Japanese list. 18 Kiga, Kenzo (1937) "[Book Review] L. Robbins; Economic Planning and International Order, London 1937. pp. 330", Mita Journal of Economics, 31(11), November 1937, 131-137. <10> Kiga, Kenzo (2000). "Anti-socialism economy and freedom: seeking for moral in community", Reformer [previously A Study on Democratic Socialism], 41(12), December 2000, 10-13. <11> Kimura, Yuichi (2004) "Lionel Robbins and Interpersonal Comparison of Utility", The Economic Review (Kyoto University), 173(2), February 2004, 50-72. <12> Komine, Atsushi (2007) W. H. Beveridge in Economic Thought: A Collaboration with J. M. Keynes et al., Kyoto: Showa-do. <16> Kumagai, Hisao and Yasuhiko Ohishi eds. (1970) A Basic Theory of Modern Economics, Tokyo: Yuhikaku Publishing CO., Ltd. <13> Kurata, Minoru (1998) An Essay on Kin-nosuke Ohtsuka, Kanagawa: Seibunnsha. <14> Lange, O. (1935) "Marxian Economics and Modern Economic Theory", The Review of Economic Studies, 2(3), June 1935, 189-201. Makino, Kuniaki (2006) "Nobuyuki Ohkuma and John Ruskin "Seiji Keizaigaku" and "Political Economy"", Bulletin of the Center fro Historical Social Science (Hitotsubashi University), No. 26, 6-22. <43> Maruyama, Yasuo (1989) Hitotsubashi during the War Period: from January 1937 to August 1945, Tokyo: Jusuikai Corporation. <45> Masini, Fabio (2007a), “Money, Business Cycle, Public Goods: British Economists and Peace in Europe, 1919-1941”, in Petricioli, Marta - Cherubini, Donatella eds. (2007), Pour la Paix en Europe. Institutions et société civile dans l’entre-deux-guerre – For Paece in Europe. Institutions and Civil Society between the World Wars, Bruxelles: Peter Lang: 169-190. Masini, Fabio (2007b), “Robbins’s Epistemology and the Role of the Economist in Society”, paper presented at the 75° Anniversary of the Publication of An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, London School of Economics, 11 Dec; forthcoming in Sunctory and Toyota International Centres for Economic Research and Development Occasional Papers, 23. Matsushima, Atsushige (2005) Can Utilitarianism Survive? Towards the Construction of Economic Ethics, Tokyo: Keiso Shobo. <44> Minoguchi, Takeo, Tamotsu Nisizawa and Aiko Ikeo (2000) "From Reconstruction to Rapid Growth", in Ikeo ed. (2000), 210-254. <46> Nakayama, Ichiro (1933) Pure Economics, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten Publishers. <30> Nakayama, Ichiro (1957) "An Introduction: Robbins' Economics", in the preface of the translation of Essay, i-v. <32> Nakayama, Ichiro (1958) "A Chronological Record made by oneself", in Shinohara ed. (1958), 1031-1042. <33> Negishi, Takashi (2001) "Alfred Marshall in Hitotsubashi", in T. Negishi, R. V. Tamachandran and K. Mino eds. (2001) Economic Theory, Dynamics, and Markets, Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 357-367. <35> Negishi, Takashi (2002) "The General Equilibrium Theory in 20th Century Japan", International Journal of Applied Economics and Econometrics, 10(3), 2002, 480-489. <36> Negishi, Takashi (2008) Development of Economics Theory, Kyoto: Minerva Publishing CO., Ltd. <37> 19 Nei, Masahiro (1989) Lives of Modern Economics in Britain: from Orthodox to Heresy, Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten Publishers. <34> Nomura, Kanetaro (1939) "Theory and Practice: Recent British Controversies on the Methodology of Economics", Mita Journal of Economics, 33(8), August 1939, 1-33. <38> Ohkuma, Nobuyuki (1929) A Tale of Robinson Crusoe in Marx, Tokyo: Dobunkan. <6> Ohkuma, Nobuyuki (1977) My Literary Retrospect, Tokyo: Disan Bunmei-Sha. <7> Robbins, Lionel C. (1932), An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, London: Macmillan. Robbins, L. (1934) The Great Depression, London: Macmillan. Robbins, Lionel C. (1935a), An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science, London: Macmillan, II edition. Robbins, Lionel C. (1937a), Economic Planning and International Order, London: MacMillan. Robbins, Lionel C. (1937b), “The Economics of Territorial Sovereignty.” In Charles Antony Woodward Manning. ed., Peaceful Change, London: Macmillan: 41-60. Robbins, Lionel C. (1939a), The Economic Basis of Class Conflicts. London: Macmillan. Robbins, Lionel C. (1939b), The Economic Causes of War, London: Jonathan Cape. Robbins, Lionel C. (1940), “Economic Aspects of Federation.” In Melville ChanningPearce. ed., Federal Union. A Symposium, London: Jonathan Cape: 167-186. Robbins, Lionel C. (1959), “The Present Position of Economics”, Rivista di Politica Economica, XLIX (VIII-IX): 1347-1363. Robbins, Lionel C. (1981), “Economics and Political Economy”, The American Economic Review. Papers and Proceedings of the Ninety-Third Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association, 71 (2): 1-10. Sakamoto, Jiro (1958) "Professor Nakayama and his Doctrine", in Shinohara ed. (1958), 1005-1030. <17> Shibata, Kei (1933) "Marx's Analysis of Capitalism and the General Equilibrium Theory of the Lausanne School", The Kyoto University Economic Review, 8(1), July 1933, 107-136. Shinohara, Miyohei ed. (1958) Stability and Progress in Economies: in celebration of 60th birthday of Professor Dr. Ichiro Nakayama, Tokyo: Toyo Keizai Inc. <18> Skene Smith, N. (1929) Economic Control: Australian Experiments in "Rationalisation" and "Safeguarding", London: P. S. King & Son, Ltd. Skene Smith, N. (1934) "British Economic Theory during the Last Four Years", The Journal of Economics, The society of economics, University of Tokyo. 4(3), March1934, 74-99. Suenaga, Takasuke (1950) "The Great Depression and Non-Marxian Economics: with a central focus on Robbins' Arguments", Keizaigaku Zashi, or Journal of Economics (Osaka University of Commerce, Nihon Hyoron Inc., 23(4), October 1950, 1-37. <19> Suenaga, Takasuke (1953) "Chapter 9: Modern Economics", in Deguchi ed. (1953), 382431. <20> Sugihara, Shiro (1980) Collected Papers on the History of Japanese Economic Thought, Tokyo: Mirai-sha Publishers. <21> Sugihara, Shiro (1987) Economic Magazines and Journals in Japan, Tokyo: Nihon-keizaihyoron-sha Ltd. <22> Sugimoto, Eiichi (1950) Explications of Modern Economics, volume 1 & 2, Tokyo: Rironsha. <23> 20 Sugimoto, Eiichi (1953) The Modern History of Economic Thought, Tokyo Iwanami Shoten Publishers. <24> Sugimura, Kouzo (1938) A History of Economic Methodology, Tokyo: Risosha. <25> Takata, Yasuma (1949) The Methodology of Economics, Tokyo: Koishikawa Shobo. <26> Talamona, Mario (1960), “Sull’evoluzione metodologica di Lionel Robbins”, L’industria, 1: 74-89. Tomita, Shigeo (1950) "Differences in thought patterns between materialism and scarcity definitions of economics", Mita Journal of Economics, 43(3), September 1950, 23-50. <28> Tsuji, Rokubei (1958) "A Methodological Basis of Economic Science: A Comment on Robbins's Essay", in Shinohara ed. (1958), 133-166. <29> Yasui, Takuma (1933) "[Review Article] Lionel Robbins, An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science. 1932. pp. ix 141. Macmillan, London", The Journal of Economics, The society of economics, University of Tokyo. 3(6), June 1933, 124-131. <46> Yasui, Takuma ed. (1980) Modern Economics and Myself: Conversations with four specialists, Tokyo: Bokutaku-sha. <47> Uzawa, Hirofumi (1970) "Problems of Bewilderment Modern Economics", The Nikkei, 4th January 1970. <5> 21