Sunday 5th January

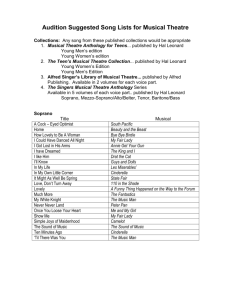

advertisement

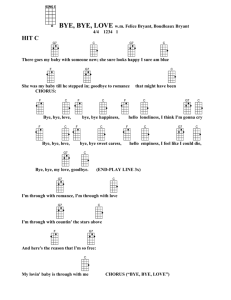

5 January 2014 HYMNS: Preacher: Leslie Griffiths 4 566 549 588 460 “Father in heaven” “Take my life and let it be” “Come let us use the grace divine” “I come with joy, a child of God” “come let us anew, our journey pursue” READINGS: Romans 12:1-5 Mark 14:22-31 YOU WILL ALL LOSE FAITH Over the Christmas period we became aware of so many people, young people mainly, who find this time of year very difficult. They’re students, they may have difficulties with the English language, or perhaps they’ve only recently arrived in the UK. And the holiday period makes them feel so very far from home. The enjoyment, indulgence, family reunions that happen all around them simply accentuate the feeling of isolation. Phil Everly died this week – he and his brother Don were the virtual founders of modern popular music. We’ve all been hearing snatches of their great smash hits of the late 50s/early 60s on our radios and television sets over recent days. These songs heave with feeling, they touch the pulse of a whole generation, and they still vibrate with long and melancholic aftershocks. Here’s my favourite (I feel so passionate about it that I’m going to quote it in its entirety): Bye bye love;Bye bye happiness. Hello loneliness; I think I´m gonna cry;I feel like I could die. Bye bye my love bye bye. There goes my baby with someone new, She sure looks happy, I sure am blue, She was my baby till he stepped in, Goodbye to romance that might have been. I´m a-through with romance, I´m a-through with love, I´m through with a-counting the stars above; And here´s the reason that I´m so free. My loving baby is through with me. Bye bye love. Hello loneliness. I feel like I could die. This became the song of a generation. It doesn’t take much imagining to move its meaning beyond the breakup of a particular relationship. It could easily sum up the feelings of emptiness and rage, alienation and uselessness that have become such a feature of subsequent pop music. I began by mentioning students in London, far from home. I went on to describe young people in the 50s and 60s singing the blues. These days, more and more, I find people who are, indeed, far from home. Not in the sense that can be remedied by a plane journey – a ticket to ride. Nor in the sense that could be reversed by the return of a lover. People are far from home in the spiritual sense too, cut off from meaning, purpose, values, hope. They are lost, despairing. The Princes Trust charity published the results of a study this week which declared that as many as 750,000 young people in the UK feel they have nothing to live for. A third of long-term unemployed people have contemplated taking their own lives. “I feel worthless,” says one young man. The young jobless are in danger of becoming the young hopeless. Organised religion, far from offering to help at this point, sometimes succeeds in doing the reverse. Christianity seems to have become associated in the minds of so many with the oppressive forces that have created a social order built on a military/industrial complex supported increasingly by an intelligence machine. Havoc is wreaked in every part of the globe. And churches are too often frequented by the living dead whose zombiefied religion repels would-be followers with its desiccated liturgies and rigid moralities. To go back to the 60s for a moment, I remember when the musical Hair (described as “American tribal love-rock”) gave its first performance. There was lots to feel uneasy and queasy about in this particular production. It lambasted the Vietnam War and urged young Americans to dodge the Draft. It was full of musical profanity and there was constant reference to the use of illegal drugs. Sexual practice ranged across a number of activities generally considered “deviational” irreverence was shown for the American flag. And, to cap it all, there was a nude scene – which became the focus of ire on the part of British Churches when the musical finally came to London. Plenty to object to. Lots of difficult stuff to deal with. Against all that, this musical was the first to be offered by a racially-integrated cast. And what do you make of these two stanzas of one of its songs: Where do I go? Follow the river Where do I go? Follow the gulls. Where is the something Where is the someone That tells me why I live and die? Follow my heartbeat. Where do I go? Follow my hand. Where will they lead me? And will I ever discover why I live and die, I live and die? It has always seemed to me that a production that asks questions of that kind is important to listen to very carefully. It seems to me that a deep yearning form meaning and direction in life lies at the heart of the production. The profanity and sexual behaviour, the difficult stances for American self-esteem and foreign policy, are surely less important than those existential questions in that song. What goo do Churches do to confirm the prejudices that people in our secular societies have about us when they simply condemn and dismiss such a production. If people are far from home (in the spiritual sense) and cut off from all that might sustain them, it’s too often true that organised Christianity must take its share of the blame for driving them out. There’s no better day for Methodist people to heed this warning, to face these facts, than this very day, the day when we renew our Covenant with God. A Covenant is an exchange of promises. It involves commitment, it’s a long-term investment. “This is how I want to live my life”. Not the next five minutes. Nor are these merely New Year’s resolutions. They are serious promises. We make them to God. And we hear over and again, the repetition of his promises to us. He has sealed his promises with his death. He has signed his writ in blood, his own blood. Let me expand and paraphrase his side of the bargain: “This is what I want to do for you – give my very self, my flesh and blood, - for you. Yes for you. It’s because I love you, you silly thing. And I’m going to go through with this to show you just how much I love you. So every time you take that little piece of bread, just think of me; when you take a sip from that cup, remember me. I love you. I love you enough to die for you. Don’t forget me.” Well that’s God side of the deal. It’s a deal he’s closed. It’s done. Our side of the bargain is, quite simply, to do our best to live in his spirit. To model ourselves on him. We are invited to be generous, imaginative, caring people who put ourselves out for others. Just as he did. And that’s about it. The amazing thing in this morning’s gospel is that Jesus knows full well, even as he makes his own commitment, that his friends, for all their fine words, will renege on theirs at the first opportunity. Once the shepherd is taken from them, then the sheep will wander all over the place. They’ll become “deserters” (in one translation), they will “lose faith” (in another). They’ll break their promises. They can protest as much as they like – and every one of them did – yet they would deny him, turn their backs on him, run away, betray him in the immediate aftermath of these words about a Covenant. The very essence of the Christian faith is found in this simple fact. Jesus is prepared to do a deal with people he knows to be incapable of delivering on their promises. Not a way to run a business. But we don’t find him cancelling the Covenant. Not at all. He entrusts the perpetuation of his cause, the proclamation of his message, to a bunch of people whose fallibility and feebleness are only too obvious. He offers a partnership to people who will never be in the same league as himself. That’s what Christianity is all about. It isn’t about power, or wealth, or hierarchies, or cleverness, or snobbery or moralising. It doesn’t expect perfect of fantastic qualities from us – just a bit of good will and self-knowledge. It’s time for us to de-clutter our Churches – to get rid of all that stuff that inhibits strangers or fills people with guilt. We must ensure that our Church is welcoming, open, loving. Then and only then will we stand a chance of re-connecting with the disenchanted; we must open our doors, our arms and our hearts to welcome the lonely, the poor, the marginalised. We are broken, often well-minded, ordinary people. Our job is to keep the road to this (communion) table open so that everyone can hear the timeless words of Jesus – this do in remembrance of me. We need to hear the commitment he’s made to us over and over and over again. Only when that sinks in will we rise to the challenge of following him and make our discipleship more than mere lip service. And then, who knows, we might just turn that lovely song by the Everly brothers on its head: Hello love. Hello happiness. Bye bye loneliness. I think I’m gonna cry I feel that you’re nearby Bye bye despair, bye bye. A very happy New Year to you all. And may we, frail and uncertain though our grasp on the deeper truths of our faith may be, continue to put our hand out into the dark in the expectation of finding it taken by the outstretched hand of God. Amen.