Beer Promotion in Cambodia - Business & Human Rights Resource

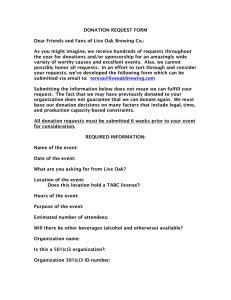

advertisement