ui team asks ethical question: can advanced materials in sports

advertisement

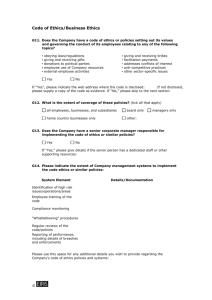

DO ADVANCED MATERIALS IN SPORTS UNFAIRLY TILT THE PLAYING FIELD I. The effects of advanced materials on sport. Historical notes and present text. II. The ethical responsibility of the engineer, and the concomitant responsibility of the educational institution of teaching ethics. III. How should one go about teaching ethics in advanced materials? IV. What worked for us? V. Application and importance for others. MOSCOW– They make unusual teammates -- two University of Idaho engineers, a sports philosopher, their co-researchers and graduate students. But they're getting international attention for raising provocative questions on the ethics of escalating high-performance equipment in sports. Leaders of the cross-disciplinary team are F.H. (Sam) Froes, director of the Institute for Materials and Advanced Processes, head of UI's material sciences and ardent golfer; Keith Prisbrey, professor of metallurgical and mining engineering and local Scout leader; and Sharon Kay Stoll, sports philosopher, education professor and director of UI Center for ETHICS* (Ethical Theory and Honor In Competitive Sports.) They have developed an undergraduate course intended to break the barrier between science and ethics, introducing the notion of "responsible science." They also advocate integration of ethics into the core curriculum at UI, and offering character education as a learned skill. Along with co-researchers, the scholarly team recently blitzed their professional fields with keynote addresses, research papers, short courses and international presentations examining the ethical use of advanced materials in sports equipment. In one paper, Froes documents the pervasiveness of advanced materials in virtually every sport -- composite baseball bats and pole vaults, titanium golf balls and clubs, bionic prostheses, spring-loaded shoes, reinforced bicycle frames, expanded "sweet spots" on tennis rackets, synthetic turf fields and other space-age enhancements that guide or project objects faster, sharper and easier. Already, major league baseball has banned all but wooden bats to keep their pitchers and short stops from facing off with 130-mph balls. PGA also has ruled against certain advanced material balls and clubs in tourneys. "We're not advocating an end to scientific discovery or its application to sports," says Prisbrey. "We're addressing the dilemmas that arise, and train students in moral reasoning to face the tough decisions straight on." The dilemmas focus on the potential for dehumanizing athletes through managed and high-tech equipment. For example, skis, snowboards and toboggans can be ergonomically redesigned and engineered of reinforced composite materials to increase speed, resiliency and performance. If the sport sanctions the equipment, it can render senseless previous records and sport history, revolutionize the game, create unfair advantages for some, risk greater harm, cost more, restrict some players or dilute the common good in other ways. "Determining the consequences is necessary to moral reasoning, but doesn't necessarily negate using the new-age materials," says Sharon Stoll, one of approximately 40 sports ethicists in the world who publish research. "I always go back to the moral imperative -- what is the purpose of the competitive sport? If the purpose of Olympic skiing is to put human skill and preparation to the test, then would these new materials and equipment in any way violate that goal, narrow or tilt the competitive field?" Prisbrey agrees that science and ethics wisely cross-pollinate. "Our engineering education accrediting board requires that all its graduates be introduced to ethics," he adds. "Our technical code of ethics requires us to defend the public health and safety at all costs, and sound decision-making can avert disasters" such as The Challenger explosion and Three Mile Island nuclear reactor accident. "So, it's thrilling to me that with a roadmap for moral reasoning, we can compete fully and aggressively -- in sports, business or life -- without violating our principles." "If we can make any conclusion," says Stoll, "it's that we must continually question sporting equipment innovation: What is good and valuable about the activity to preserve, how will the new equipment/materials enhance these goals, how will the equipment be distributed and will unfairadvantages result? Then, we must be open to debate." "My goal," adds Prisbrey," is to present moral reasoning in a material world. I don't think there's ever been as great a need for this methodology as there is now." CONTACTS: Keith Prisbrey, professor of metallurgical and mining engineering, (208) 885-6376, (208) 882-1807 (home), pris@uidaho.edu; Sharon Kay Stoll, sports philosopher, education professor and director of UI Center for ETHICS*, (208) 885-2103, (509) 595-0795 (cell), (208) 875-1443 (home), asstoll@uidaho.edu; Francis H. (Sam) Froes, director of Institute for Materials & Advanced Processing, (208) 885-7989, imap@uidaho.edu -30- NH-6/26/01-ED/ENGRG Bios: Sharon Stoll, UI professor of physical education, ETHICS* Center director, and winner of UI Teaching Excellence and Outreach awards, is a former public school teacher, athlete (competitive skating), coach, and leading expert in ethics in competitive sports. She has a doctoral degreein sport philosophy from Kent State University, and is known worldwide for her research and teaching skills in character development. Keith Prisbrey, UI professor of materials and metallurgical engineering, professional engineer, is an expert in plasma etching and electrostatic sorting of minerals on nearEarth asteroids. He has advanced degrees from University of Utah and Stanford, is active in professional societies, and is a Scoutmaster. F. H. (Sam) Froes, director of UI's Institute for Materials and Advanced Processes, is a Fellow of American Society of Materials and the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences. He has advanced degrees in physical metallurgy from the University of Liverpool and University of Sheffield, and many honors for his research and distinguished service. He formerly worked at Crucible Research Center in Pittsburgh and the USAF Materials Lab in Dayton, Ohio.