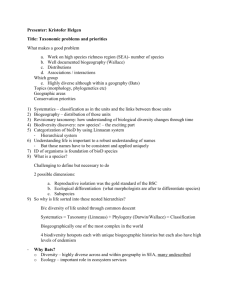

USA Baseball`s Youth Committee Issues Statement on Non

advertisement

USA Baseball’s Youth Committee Issues Statement on Non-Wood Bats

WILLIAMSPORT, Pa. (Jan. 25, 2007) – The Youth Committee of USA Baseball today issued the

statement below regarding non-wood bats.

Little League International is a member, along with other youth organizations, of USA Baseball. Little

League also holds a seat on the USA Baseball Board of Directors.

USA Baseball often coordinates research that affects all youth baseball organizations. For example, USA

Baseball was instrumental in the recent change to the league age determination date by all youth

baseball organizations.

----USA Baseball, the National Governing Body (NGB) for the sport of baseball as designated by the

Amateur Sports Act of 1978, recently held a meeting of its National Youth Membership, and on behalf of

the following organizations has released the following statement:

1. American Amateur Baseball Congress (AABC)

2. American Legion Baseball

3. Dixie Baseball

4. Little League Baseball, Inc.

5. Babe Ruth Baseball

6. PONY Baseball

7. National Baseball Congress / Hap Dumont Baseball

8. Amateur Athletic Union (AAU)

9. United States Sports Specialties Association (USSSA)

10. National Police Athletic League (PAL)

11. T-Ball USA

PERCEPTION: Aluminum bats are more dangerous than wood bats.

The National Consumer Product Safety Commission studied this issue and concluded in 2002 that there

is no evidence to suggest that aluminum bats pose any greater risk than wood bats. Multiple amateur

baseball governing bodies, including the NCAA, National High School Federation, Little League

International, PONY, et al, all track safety statistics and have concluded that aluminum bats do not pose

a safety risk.

PERCEPTION: Balls come off aluminum bats faster than wood.

Since 2003, all bats are required to meet the “Bat Exit Speed Ratio” (BESR) performance limitation,

which ensures that aluminum bats do not hit the ball any harder than the best wood bats.

PERCEPTION: Injuries from aluminum bats are more severe than with wood bats.

Two out of the three deaths from a batted ball in the last decade came from wood bats. Dr. Frederick

Mueller, Director of the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research, has indicated from his

studies that catastrophic injuries from wood bats may be more frequent than aluminum bats.

PERCEPTION: The Brown University study proves that aluminum bats hit the ball harder than wood bats.

This study is irrelevant by today’s standards. All of the bats used in the Brown study would not be

allowed to be used today, because they do not meet the BESR standard.

PERCEPTION: The use of aluminum bats places children at an unacceptable risk of injury.

A study from the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research shows that there have been

only 15 catastrophic batted ball injuries to pitchers out of more than 9,500,000 high school and college

participants since 1982.

During the last five years a number of states, individual organizations, city councils, and others have

proposed the banning of metal baseball bats on a number of different levels. These actions have

typically been in reaction to a catastrophic injury as opposed to being based on creditable injury data or

research. In May of 2002 the Consumer Product Safety Commission stated, “The Commission is not

aware of any information that injuries produced by balls batted with non-wood bats are more severe

than those involving wood bats”. This statement was true in 2002 and it is true in 2007.

The Medical/Safety Advisory Committee of USA Baseball was initiated due to the lack of injury data

needed to make decisions affecting the safety of baseball participants. Prior to 2005 there has not been

significant research comparing injuries to baseball pitchers from metal bats versus wood bats. In 2005

the USA Baseball Medical/Safety Committee initiated a three year research project comparing line drive

baseball injuries to pitchers from metal bats and wood bats. Metal bat injury data were taken from the

National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance System and wood bat injury data

collected from college summer leagues (NCAA recognized college summer league teams all use wood

bats).

After two years (2005 and 2006) of collecting batted ball injury data to the pitcher from 93 NCAA

college baseball teams and 246 college summer league teams there have only been 17 injuries to NCAA

college pitchers and 15 injuries to college summer league pitchers. Only 32 injuries after 331,821 balls

were hit into play (Balls hit into play are calculated by taking the number of at bats and subtracting

strike outs and bases on balls). The injuries in the summer leagues were more severe than the NCAA

injuries. One-third of the summer league injuries involved the head and face as opposed to none in the

NCAA. The third year of the study will be completed in 2007.

What this data does indicate is that injuries to the pitcher from batted balls are very rare and can

happen while using metal or wood bats. There is no data to indicate that the few catastrophic injuries to

baseball pitchers from metal bats would not have happened if the batter was using a wood bat. Before

any sport makes rule changes, equipment changes, or other changes related to the safety of the

participants, it is imperative that these changes are based on reliable injury data and not anecdotal

information.

----More information on this subject is available at these links:

http://www.littleleague.org/media/bats.asp

http://www.littleleague.org/rules/2005bathelmetrulechanges.asp

http://www.littleleague.org/media/InjuredPitcherStats.pdf

LITTLE LEAGUE INTERNATIONAL STATEMENT ON NON-WOOD BATS

Little League International has received numerous inquiries from its volunteers and media

regarding the safety of non-wood bats.

Background

Recent innovations in metal alloys have allowed a reduction in the weight of some models of

bats, while allowing the bats to remain in conformity with the length and diameter

guidelines in the various divisions of Little League Baseball and Softball. Some volunteers

and those in the media have raised questions about whether the weight of the bats used in

Little League games should be limited, relative to the length.

Non-wood bats were first developed, partly through research by Little League, as a safer

and more cost-effective alternative to wooden bats. Non-wood bats were first used in Little

League in 1971, and have almost completely replaced wood bats in all divisions of play.

Wood bats, which can break in half if not used properly, are now widely used only in

professional baseball.

As a member of USA Baseball, the governing body for all amateur baseball in the U.S., Little

League Baseball and Softball follows the recommendation of the USA Baseball Medical and

Safety Advisory Committee. The position of the Advisory Committee is that further research

and data needs to be collected before any changes are made to Little League rules

regarding the weight of bats. There is currently no rule in any division of Little League

Baseball or Softball that places a maximum or minimum limit on the weight of bats.

Statement

At present, injury data in all divisions of Little League Baseball and Softball shows there has

been a 69 percent decrease in reported injuries to pitchers as a result of batted balls since

1992. Data on injuries to pitchers is being used because the pitching position is nearest the

batter, and the pitcher is the least likely among all fielders to be fully prepared when the

ball is hit.

During that same period, the number of injuries to other fielders as a result of batted balls

has remained relatively constant or decreased. A summary of the data is attached, along

with participation figures and the current bat specifications for each division.

In 2003, nearly 108,300 children ages 5 to 14 were treated in hospital emergency rooms for baseballor softball-related injuries according to the National Safe Kids Campaign (NSKC). However, only 42

injuries in Little League Baseball and Softball activities, ages 5 to 18, required an insurance claim to be

paid that year. Among the same ages in the same year, more than 185,700 football injuries and

205,400 basketball injuries were treated, NSKC reported.

Annually, less than three-tenths of one percent of U.S. Little Leaguers are injured in games or practices

to the point of requiring medical treatment. Injury data for Little League are obtained through analyzing

medical claims on accident insurance provided by Little League though AIG Insurance. More than 95

percent of the chartered Little League programs in the U.S. are enrolled in the Little League Group

Accident Insurance plan.

In conclusion, there appears to be no indication that would cause Little League to mandate a limit on the

weight of bats or the use of non-wood bats, based on the most current facts. Statistics show that Little

League’s record on safety continues to be outstanding not only among youth sports, but in baseball and

softball in particular.

However, Little League Baseball will continue to monitor this situation closely, and will react accordingly

and appropriately when indicated.

Rule 1.10 (baseball only)

NOTE 3: Beginning with the 2009 season, non-wood bats used in divisions of play Little League

(Majors) and below must be printed with a BPF (bat performance factor) rating of 1.15 or less.

What does this mean? Bat manufacturers agreed several years ago that the BPF (bat

performance factor) of bats they are now manufacturing will not exceed a 1.15. The BPF is a

formula that measures how fast a baseball comes off the bat. Starting on Jan. 1, 2009,

however, all bats used in the Little League (Majors) Division and below must be designated

(printed) with a BPF of 1.15 or less.

NOTE 4: Non-wood bats may develop dents from time to time. Bats that cannot pass through the

approved Little League bat ring must be removed from play. The 2 ¼ inch bat ring must be used for

bats in all softball divisions, and in the Tee Ball, Minor League and Little League Baseball divisions of

baseball. The 2 ¾ inch bat ring must be used for bats in the Junior League, Senior League and Big

League divisions of baseball.

What does this mean? For a non-wood bat to become dented over time is normal. But some

umpires have been disallowing bats that are slightly dented. As a result, Little League will

providing a number of Little League Approved bat rings at no charge to every league for use in

all divisions of play. Umpires who are active in the Little League Umpire Registry (details on

joining the registry are here http://www.littleleague.org/umpires/index.asp) also will receive

one bat ring at no charge. Additional bat rings may be purchased from Little League

International or the Regional Center. The ring has holes for both sizes and is made of sturdy

plastic. If the bat passes through the proper ring, it is “legal.” (Obviously, however, if a bat has

visible cracks in it, it should not be permitted in a game.) You can see an example of the ring

here: www.littleleague.org/media/images/LL_Bat_Rings.jpg

Rule 1.10 (softball only)

NOTE 3: Non-wood bats may develop dents from time to time. Bats that cannot pass through the

approved Little League bat ring must be removed from play. The 2 ¼ inch bat ring must be used for

bats in all softball divisions, and in the Tee Ball, Minor League and Little League Baseball divisions of

baseball. The 2 ¾ inch bat ring must be used for bats in the Junior League, Senior League and Big

League divisions of baseball.

What does this mean? For a non-wood bat to become dented over time is normal. But some

umpires have been disallowing bats that are slightly dented. As a result, Little League is

providing five Little League Approved bat rings at no charge to every league for use in all

divisions of play. Additional bat rings may be purchased. The ring has holes for both sizes. If

the bat passes through the proper ring, it’s legal. (Obviously, if a bat has visible cracks in it, it

should not be permitted in a game.) You can see an example of the ring here:

www.littleleague.org/media/images/LL_Bat_Rings.jpg

Rule 1.16 and 1.17 (All levels of baseball and softball)

Warning! Manufacturers have advised that altering helmets in any way can be dangerous. Altering the

helmet in any form, including painting or adding decals (by anyone other than the manufacturer or

authorized dealer) may void the helmet warranty. Helmets may not be re-painted and may not contain

tape or re-applied decals unless approved in writing by the helmet manufacturer or authorized dealer.

What does this mean? It means if an umpire or other league official notices paint or a decal

on a helmet, and if the a umpire/league official has reason to believe that the manufacturer or

authorized dealer did not grant approval (in writing) for the paint or decal to be applied, that

helmet should not be used in a game or practice.

Creighton J. Hale: Helmet and bat inventor who helped

mold world's largest youth sports program

Copyright © 2004 by E. A. Kral

For nearly a half century, Hardy, Nebraska native Creighton J. Hale served as a major leader

in the field of sports safety research on the amateur and professional levels. And he greatly

contributed to molding Little League Baseball and Softball into the world's largest and most

respected organized youth sports program.

An exercise physiologist, he first conducted a scientific study of professional baseball players

while an associate professor at Springfield College in Massachusetts from 1951 to 1955 at

the request of the renowned major league executive Branch Rickey.

Hale developed an electronic testing device to measure reaction times of major league

players and various facets of the game. In 1960, he published his findings in Roche Medical

Image.

Meanwhile, he had begun in 1955 his career as a researcher and later an executive with Little

League Baseball, based in Williamsport, Pennsylvania, to study the effects of athletic

competition on young boys. Two years earlier, after the organization's World Series was first

televised, questions were raised about the healthiness of the sport for its participants.

His finding was that the emotional reaction of the parents and coaches was much higher than

that of the players. Within minutes of a competition ending, the children were

physiologically back to normal. However, the parents and coaches often showed elevated

heart rates and other symptoms hours later.

Another research project involved the discovery that more young batters were hit by pitches

than major league players. He electronically timed the reaction speed of batters, and learned

that children had less time to react to a pitch.

So the Little League pitching mound was moved back from 44 feet to 46 feet, and the ratio of

the bat speed to pitch speed was thus matched, and the chances of injuries were reduced

significantly.

For several years Hale developed equipment to prevent injuries. Even though the National

Federation of State High School Associations and the National Collegiate Athletic

Association, both now headquartered in Indianapolis, Indiana, had mandated in 1955 and

1958 respectively that their baseball teams use fiber-glass helmets, the material did not

withstand the impact of a pitched ball, and the design did not protect the temple area.

After he developed the double-earflap batter's helmet, originally made of polycarbonite (a

light-weight plastic) but now may include a variety of light-weight plastics that withstand

thrown balls and protect the temple area, Little League made its use mandatory by Little

League players in 1961.

Eventually, the double or single flap batting helmet, based on his invention, became widely

used on virtually all levels of baseball and softball. And thousands of serious injuries--as a

result of batters or base runners hit by balls--have been prevented.

Its use was mandated by the National Federation of State High School Associations for

baseball in 1970 and girls softball in 1976, by the NCAA for baseball in 1980 and women's

softball in 1986, and by the Major Leagues in 1983.

Hale pioneered other equipment that improved the safety of the game and the enjoyment of

children. Wood bats could shatter when not handled properly, and they were expensive to

maintain over a period of years.

So he co-developed with Alcoa Sports the aluminum bat, which was lighter and more durable

than wood, and made the game easier for children to learn. First used by Little League in

1971, his bat was also used by the NCAA baseball and women's softball teams for a few

years after 1975 and 1982 respectively until bats of other non-wood materials were allowed.

The non-wood bat is now widely used on almost all levels of amateur play. The National

Federation of State High School Associations first permitted the aluminum bat for baseball in

1975 and for girls softball in 1981, but other material is now allowed, subject to approval by

appropriate governing organizations.

Another of his innovations was a one-piece catcher's mask attached to a helmet that could be

quickly removed. Made of lightweight plastic, it was produced after a previously used mask

with magnesium bars led to injury.

Mandated for use by Little League in 1973, it became required--after sufficient testing by the

National Operating Committee on Standards for Athletic Equipment --for use in high school

baseball and girls softball in 2003, and the helmet must be dualflap.

A catcher's helmet was first required for girls high school softball in 1976, and a throat

protector six years later. NCAA women's softball catchers were required to use a helmet with

a mask in 2000. Some Major League Baseball catchers use a helmet of similar design while

others use "skull" helmets without earflaps.

Hale's other safety developments were a catcher's chest protector with throat guard, rubber

spiked baseball shoes (which for several years replaced the steel-spiked kind), and a portable

nylon outfield fence that players could run into at full speed but not hurt themselves.

He donated his patents to Little League Baseball.

Outside of sports, he assisted in the development of the infantry pack in 1954 for use by the

U.S. Army.

In 1976, he was elected chairman of a committee on consumer product safety standards for

the American Society of Testing and Materials.

That same year he also became chairman of a group of scientists with the National Research

Council of the National Academy of Sciences who were asked to develop a new military

helmet, and later his research aided the development of a lightweight bullet-resistant vest

used by the military and law enforcement personnel.

He co-designed a one-piece helmet made from a space-age plastic called Kevlar that offers

more protection than the Army's old steel helmet which was worn over a helmet liner.

First used in combat during the U.S. liberation of Grenada in 1983, it resembles the shape of

the German steel helmet of World War II. It is now standard issue of U. S. ground forces.

Aside from his work as a researcher, Creighton Hale also served as an innovative executive

for Little League Baseball, with its mission set previously in 1939 by founder Carl E. Stotz as

the development of good citizens rather than good athletes through "coaches teaching kids

respect and discipline and sportsmanship and the desire to excel."

In the beginning, Little League involved players of ages 9-12, but in 1961 it added a Senior

League for ages 13-15, and in 1968 a Big League for ages 16-18.

Its first World Series in 1947 consisted primarily of teams from Pennsylvania, and eventually

became annually televised. But ten years later, the first non-U.S. team to win the

championship was from Monterrey, Mexico, and there were more than 4,000 leagues in the

United States, Canada, and Mexico.

In the decade of the 1960s, the organization opened its new international headquarters

building at Williamsport, opened regional headquarters offices in Canada, California, and

Florida, and was granted a Charter of Federal Incorporation by the U.S. Congress.

Hale served as its third president from 1973 to 1994, and as chief executive of the board from

1983 to 1996. Under his leadership, the number of leagues enrolled increased from 10,006 to

21,711; teams from 90,000 to 198,347; participants from 370,000 to 3,125,205; and countries

from 31 to 83.

He helped open additional regional headquarters offices in Connecticut, Indiana, and Texas,

and international representative offices in Japan, Poland, and Puerto Rico.

In 1974, introduced for girls were Little League and Senior League Softball, and six years

later Big League Softball. Added to baseball in 1979 was Junior League for 13-year-old

boys.

Initiated also was Tee Ball for ages 5-7, which involves the use of a batting tee without a

pitched ball, and Minor League for ages 7-12, which is for anyone who doesn't qualify for

Little League.

The Challenger Division, intended for mentally and physically disabled children, was added

in 1990. And among special projects Hale promoted were partnerships with federal agencies

for drug and alcohol education, tobacco prevention, and traffic safety.

At the turn of the 21st century, Little League Baseball and Softball had become the world's

largest youth sports program, serving boys and girls ages 5 to 18 in all 50 states and more

than 100 countries. By 2001, the year Hale retired as its senior advisor, his impact had been

amply recognized by his peers at all levels.

Among his numerous awards and honors have been the 1976 Robert J. Painter Memorial

Award for "meritorious service in the field of standardization" of protective equipment of

amateur and professional sports, the 1995 Rawlings Golden Glove Award for his service to

Little League, and the 2000 James R. Andrews Award for Excellence in Baseball Sports

Medicine. His entry is in American Men & Women of Science, Vol 3 (2003).

Born in 1924 at Hardy, Nuckolls County, Nebraska, one of five children of Russell and Anita

Fay Hale, both teachers, Creighton was raised on a nearby farm, and attended the Hardy

Public Schools, where he graduated in 1942.

Active in athletics, he was quarterback of the school's state championship six-man football

team, and was named in the December 7, 1941 Omaha Sunday World Herald as Nebraska's

outstanding six-man quarterback of the year. The following spring he set a state record in the

half-mile run, and was recognized by the Omaha newspaper as one of the state's two-sport

stars.

After attending the University of Nebraska-Lincoln for one year, he spent a year at Doane

College in the V-12 officers training program for the U.S. Navy. At both institutions he

participated in athletics.

Following active duty during World War II, he earned his bachelor's degree from Colgate

University at Hamilton, New York in 1948, his master's from Springfield College in 1949,

and his doctorate from New York University in 1951.

Creighton J. Hale is married, raised three children, and resides at Williamsport.

For more information, consult "700 Famous Nebraskans" on the Internet at www.nsea.org or

www.beatricene.com/gagecountymuseum or www.nebpress.com.

What's in an aluminum bat, anyway?

When aluminum bats were first introduced, the lower strength 6061, 6063, and 7005 alloys were used. As the designs and the applications

became more sophisticated, better alloys were required. Continued development of alloys is taking place. Aluminum bats were first made in

the early 1970�s. The NCAA legalized aluminum bats in 1974.

The list below was compiled between 1996 and 2003. Since then alloys have remained pretty much the same, with some minor adjustments

to the amounts of zinc, magnesium, scandium, nickel and other elements. Most every year bat and aluminum companies make some new

variation and give it a new name. But since there is no major change to the alloy, the process of extruding the alloy has become more

refined. Sometimes the old alloy and the new process generates a new name for the alloy, but the basic elements are the same.

The biggest difference year to year is the manipulation of wall thicknesses to produce more durability and trampoline effect. Research and

development has focused more on this aspect of the design producing some of the best bats ever made. So when someone says that the new

bats are the same bat with a new paint job, that isn't exactly accurate.

Alcoa's Cu31: Prior to 1996 aluminum, the top-of-the-line softball bats offered by the bat companies were made out of an alloy designated

Cu31. This extremely popular Al-Zn-Mg-Cu alloy is more commonly known as 7050. The trademarked designation Cu31 means that not

only is the alloy 7050 but that it was supplied by ALCOA.

Alcoa's C405: C405 is the trademarked designation of aluminum alloy 7055 when supplied by ALCOA to the bat industry. Worth was the

first to introduce C405 in softball bats in 1996 and since then, essentially all major producers of bats use C405 in most, if not all, of their

top-of-the-line bats.

C405 Ultra (Plus) is the '98 to present version of C405, which has undergone even further optimization of the heat treatment process

resulting in an even stronger version of the alloy. C405 Ultra was introduced in the 1998 line of Easton bats. But the composition of C405

has remained the same throughout the years. It is the manner in which the alloy has been heat treated that has changed. But the outcome is

what counts -- stronger bats.

C555 was introduced by Alcoa for the year 2000. C555 is a unique blend of Scandium and other metals that is slow aged to produce an

aluminum that is reported to be 8-10% stronger than C405. At print time of this catalog, no more information could be found regarding

exactly what is in it, but it does seem as though Alcoa has manufactured an aluminum similar to SC500 in that it has trace amounts of

scandium and that this makes for an even thinner walled bat with added durability. It is also the first Alcoa aluminum to be manufactured

specifically for aluminum bats. Bats made with this alloy have performed very well so far.

Sc777 is Easton's designation for the alloy used for the aluminum shell in the Easton Connexion, Z-Core, and Triple 7. This alloy was

developed jointly by Kaiser Aluminum and Ashurst Technology for exclusive use by Easton. The composition for this alloy does not fall

exactly in the range for any of the common 7xxx alloys but is most similar to 7055. What is so special about this alloy is the presence of a

dilute Sc addition. Scandium is a very rare, expensive, and lightweight metal. When added to Aluminum in dilute quantities it is responsible

for increased strength from Al3Sc precipitation, enhanced weldability, and significant resistance to recrystallization. SC777 is a more

advanced version of the old SC500 alloy. The Z-Core Series of bats also have strands of titanium in the carbon fiber core for more

durability and a bigger sweet spot.

Sc888 is an improved version of Sc777 with an "Advanced Metal Matrix™ which provides 4ksi additional strength with 10% additional

toughness."

Sc900 is a continued improvement of the successful Sc777 that has proven to be stronger and more flexible than ever before.

3DX is a trademark for fiber metal composites in bats from Worth. Fiber Flex Technology is a new 50% carbon, 50% fiber glass shell that

allows for greater flexibility in the shell (50% fiber glass increases flex) while maintaining the same durability standard (50% carbon

maintains stiffness).

GX4 is the latest version of Worth's patented 3DX technology. 3DX was Worth's highest selling brand of all time. GX4 has 50% less

carbon to make the bat hotter out of the wrapper with no break-in period. This also increases the flex properties. The patent pending GX4

shell is constructed of materials that are 4 times stronger than aluminum.

DRS The first composite dynamic shell bat. It has an enlarged sweet spot with a better feel. This exclusive patent pending DRS (Dynamic

Response System) technology blends multiple components which optimize performance, power, feel and durability.

MG46 is a magnesium enhanced, exclusive new alloy from Worth. Magnesium enhances the hardness characteristics of alloys while

maintaining lightweight properties. Magnesium (Mg) is 46% lighter than Scandium (Sc).

WS23 is a brand new alloy exclusive to Worth softball bats. We have not heard much about this new alloy. Here's what Worth has to say:

Never before has the EST seen an alloy as strong as the exclusive Worth WS23 alloy. EST is currently the #1 selling softball technology in

the world! It's new for 2002! They also claim it is 9% stronger than C555. Our best guess is that it is similar to C555 and SC777.

Scandium XS - New for exclusively from Louisville Slugger and Alcoa. Scandium XS, developed by Alcoa and enhanced by Louisville

Slugger, features double the amount of Scandium as offered by other aluminum alloy suppliers making it the most advanced Scandium

based alloy on the market. Scandium XS added to aluminum tightens the alloy grain structure, which is key to an alloy�s tensile strength

and durability. A proprietary alloy heat treatment, developed by Louisville Slugger R&D Engineers, maximizes the bat�s overall design,

performance and durability. This alloy basically replaces C555 for Louisville Slugger products. From what we can tell, they have taken the

C555 alloy and enhanced it by pouring a mixture of extra Scandium and other elements over the outer bat wall. This fills in any

microscopic gaps or crevices on the surface of the bat to make the bat more durable.

GEN1X Louisville Slugger, the world�s leading bat manufacturer, and Alcoa, the number one supplier of aluminum bat tubing, have

teamed up to offer GEN1X —The strongest and toughest alloy ever developed for aluminum bats. In aluminum bat construction, the

alloy�s “yield strength” is key to bat design, performance and durability. GEN1X, the strongest alloy on the market, is one of the first

aluminum bat alloy to measure over 100 ksi (THE MEASUREMENT OF AN ALLOY�S STRENGTH). The result is the most

technologically advanced line of aluminum bats to ever be developed. Years in the development process, Alcoa Research and Development

Engineers formulated a breakthrough combination of Aluminum, Zinc, Copper, Zirconium, Magnesium and traces of Titanium to obtain

this incredible strength. GEN1X�s cutting edge toughness and strength allows Louisville Slugger to design a line of bats with the ultimate

combination of balance, wall thickness, performance and durability. In an unprecedented move - GEN1X, the newest and most

technologically advanced aluminum bat alloy ever developed by Alcoa, is offered exclusively by Louisville Slugger.

GEN1X with Scandium In aluminum bat construction, the alloy's strength is key to bat design, performance and durability. GEN1X with

Scandium combines the ultra strong GEN1X and Scandium, the best alloy-strengthening additive available for aluminum bat development.

The result is an alloy with unprecedented levels of strength and toughness.

Dynasty's alloy is an improved version of the successful GEN1X alloy. The process has been refined and the result is a stronger and more

durable alloy with improved performance.

What does this mean? Thinner walled aluminum bats have a much bigger sweet spot and provide the batter with two very noticeable

advantages. First, the bat can be made lighter, especially in youth and fast pitch bats.

Second, the thinner walls give the bat a "trampoline effect". This means that when the bat strikes the ball, the aluminum actually springs in

and then instantly springs back out, to trampoline the ball off the bat like a tennis racket. The big draw back is durability. Whenever you

bend metal it causes metal fatigue. This could result in dented or cracked bats. The less expensive bats, usually made of 7046 or 7050

aluminum, will last longer because they have much thicker walls, are much heavier, and do not trampoline. Which bat is right for you? That

depends on your budget, but the trampoline effect of the thinner walls and lighter alloys do provide an exceptional advantage.

Bat Durability - a contradiction when you think of the money a good bat costs. As a consumer you should know that durability and

performance are not synonymous. Please keep in mind you get a 1 year (or more) warranty with your bat. There is a reason for this: high

tech bats fail. If your bat dents, cracks or goes dead, even after only a few at-bats, do not think there is a problem. This is very normal.

You must realize that you paid that much for your bat for performance (pop and distance), not longevity. Should your bat fail, don't panic.

Click here and use the warranty. Also keep in mind that The Batter's Box cannot take care of the warranty for you. All of the bat

manufacturers have taken this out of all the retailers' hands; it's not just us. And please save the receipt we send you. You must have it to

use the bat warranty.

Aluminum bats no more dangerous than wooden ones

By Stephanie Harris

(U-WIRE) PROVIDENCE, R.I. -- Aluminum baseball bats may hit the ball faster and harder

than wooden ones, but they are not more dangerous, according to new research by Brown

University Associate Professor of Orthopaedics J.J. Crisco.

The Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association is considering banning the use of

aluminum bats in high school play, but Crisco's research suggests such a step would be

unnecessary.

"The data does not support an increased risk with aluminum baseball bats," he said.

The Massachusetts organization is using Crisco's research as evidence to support its claim that aluminum bats are

more dangerous. It hopes to ban the use of aluminum bats in all high school games starting in the 2004 season. Yet

Crisco cautioned against associating ball speed with injury rate.

"If you look at [the injury rate] scientifically, baseball remains one of the safest contact sports. ... To make a decision for

aluminum based on data is not supported," he said.

Crisco, whose research focuses on injury prevention, was funded by the NCAA to do a study on the differences between

the two types of bats. The study found that aluminum bats "hit the ball faster more often," Crisco said.

Two factors contribute to this increase in ball speed: The faster swing speeds that occur with aluminum bats, and the

trampoline effect. The trampoline effect is a term describing the elastic properties of the bat that allow the ball to come

off faster.

"When the ball hits the bat," Crisco explained, "energy is lost as the ball deforms, and the more energy lost, the slower

the hit. Aluminum bats are believed to collapse or bend when the ball hits, allowing the ball to deform less and therefore

lose less energy," he said.

Major league baseball uses only wooden bats. The Brown baseball team uses aluminum bats during the season,

although they practice with wooden bats.

Aluminum bats hit the ball farther than wood, members of the baseball team said, but it is more beneficial to practice

with wood, as it is harder to hit the ball well.

"Our coach likes to use wood because wood really teaches you how to hit," said William Cebron ('05), a member of the

team. "If you get jammed or hit the ball on the end of the bat with wood, the bat's going to break. So you have to hit solid

and get the head of the bat on the ball, whereas with aluminum you can get jammed or hit on the end and still get a hit,"

he explained.

Cebron said he hits the ball farther and harder with aluminum bats. "You can hit anywhere up and down on the

aluminum bat and you can still hit it pretty hard," he said.

He said he thought that wooden bats would be safer because it is more difficult to hit the ball hard.

Christopher Contrino ('05) agreed that the ball goes farther with aluminum. With wood, "you have to have a true swing

on the ball, nice solid contact to get a base hit. The ball jumps off the bat much quicker" with aluminum, he said.

He was not convinced that the switch to wood bats would be safer, however. "Accidents are kind of rare. They don't

happen too often, but when they do, they are severe at times. Making the change over to wood could make things a lot

easier, but you could still get injured," he said.

Although Crisco's research does not support a switch to wooden bats for safety reasons, Crisco said he is not against

making such a change.

"If they prefer to use wood bats, they have the option of doing that. They have to say that they're making the decision

based on their preferences" as opposed to scientific data, he said.