Assess the extent to which the official statistics on crime and

advertisement

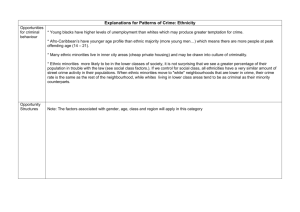

To what extent do the official statistics on crime and ethnicity provide a valid picture of the criminal activities of ethnic minorities? The purpose of official statistics is to provide us with an unbiased, objective and informative look at crime rates within the UK. However, although the statistics themselves may, to a certain extent, be reliable, the way in which they are obtained is not. Police in different areas may deem certain areas of crime a priority and thus report and record these accordingly. Also, biases within the system itself against those from ethnic minorities may affect the resulting statistics to portray an uneven account of criminal activity. The relationship between crime rates and ethnicity is extremely complex due to other factors such as the difficulty of identifying a person’s ethnic origin and the cultural and social differences between ethnic groups. It has been shown on a variety of occasions that male black youths are disproportionately selected by the police to be ‘stopped and searched’; this then results in higher numbers of black youths being charged with offences as they have been caught doing so. However, the same crimes are probably being committed by other subcultures within society, but as both the media and police do not focus on them, they are not being seen. There are many flaws with official statistics and therefore their reliability. For example, there are sections of crime that are not dealt with by the police; the management as opposed to involving an outside force, for example, may deal with crimes within a company. Also, not all crimes would be recorded or reported by the police, for example it has been shown that police are willing to let middle class youths ‘get away’ with more as they believe that they will grow out of such behaviour and become high achieving adults – the same could be implied of white youths, as black boys do stereotypically worse at school, the police may believe that they will not achieve much later on and therefore are less lenient with their behaviour. There is also the very important admittance by the police authorities who have admitted to “Institutionalised racism” within the police force. This not only refers to bias towards specific ethnic groups of the wider society, but also racism ethnic the police force itself which influences people from ethnic backgrounds decision to join the force. Disproportionate police figures reflect to the community the uneven balance of those from ethnic minorities. Police, public and judicial bias against ethnic minorities caught in the criminal justice system are such that outcomes are more likely to result in those from ethnic minorities being labelled as criminals. Lea and Young stated that coercive policing imposes rules on an area without understanding the culture, as there is no trust of local people evident. This results in the ethnic minorities of inner cities identifying themselves as ‘against’ the police. Also, due to a lack of information, the policing of the area is not effective, this consequently creates a vicious circle, which then worsens the police/public relations as, due to lack of communication, either side relies upon stereotypes which lead police to enact "military policing" stopping suspects and alienating those whom need help in the process. The social order is thus undermined by injustice. According to the British Crime Survey, youths of Afro-Caribbean origin are more likely than any other group to be stopped. This obviously has implications for official statistics, as they would be unfairly represented. However, that said, Stevens and Willis (1979) studied the relationship between crime and ethnicity, and were able to conclude that there was no relationship between the proportions of ethnic minorities and the amount of crime. The media often targets ethnic minorities when concerning crime, labelling them as ‘folk devils’ whereby they are portrayed as troublemakers. This disproportionate and biased view conveyed by the media often seeps though to the public, ensuing a panic about crime rates. This concern then leads the police to issue a ‘crack down’ on certain elements of crime, targeting people of ethnic minorities who get arrested more frequently, which makes the police seem as though they have done their job. This overarresting is then reflected in official statistics, making the police seem right. The complexities of individuals affect the statistics. A person is comprised of many different aspects of themselves; for example, a man can be black and working class. This comprises three different factors within crime: gender, ethnicity and class. How can he be defined as ‘black’ if he is also working class? This also leads to the question of which category in statistics he would be placed in if he were to commit a crime. Methodologically, this compilation of many factors into one results in a distortion of the social reality of various components. Official statistics do not provide a valid picture of the criminal activities of ethnic minorities as there are too many variables in the collation process to consider. Also, it has been shown that police priorities and biases heavily influence what is included in such statistics. The above essay is not perfect. It is a tad descriptive and should be put in context - in other words, it needs to explain why official statistics under-record crime IN GENERAL, and therefore why this is likely to be less so for ethnic minorities, given the media and police focus on them - which has been well described. To this end I have prepared notes which you might find helpful in your analysis of how this essay could have been even better: The official crime statistics cannot take account of unreported crime – hence they can be seen as GENERALLY inadequate, and not simply when applied to ethnic minorities. There are many reasons why crimes so unreported – victims may fear the consequences from criminals if they turn to the police; they may fear the police themselves; they may believe the police will be unable to solve the crime; they may be embarrassed (in cases of rape, sexual assault, domestic violence); in some close-knit communities, there is a tendency to deal with crime internally and not involve the police; some crimes are seen as too trivial to report; some victims are themselves criminals; some may see the crimes as victimless (drug selling and taking; vandalism against public property). Methods of recording/counting crimes have altered since 1998 – the effect has been to add about 600,000 a year (up 14%) – the stress is now on the number of victims rather than the number of offences (so, for example, five car thefts in the same parking lot now counts as five crimes rather than one). New categories have been added too – possession of drugs, common assault, assault on a police officer, cruelty to children, vehicle interference, dangerous driving. Perhaps 70% of crimes go unrecorded. Moral panics and police initiatives have dramatic effects on the recorded crime rate – if a particular issues is exaggerated/highlighted by politicians or in the press, then the public may report it more; police respond by targeting the particular issue, in order to be seen to be tackling the problem, so more arrests and an increase in the recorded crime rate. This is called deviance amplification; mugging is the classic example. In the particular case of ethnic minorities, many live in high crime areas; this is a key causal factor leading to low level of recorded crime – hence official statistics may under-estimate number of ethnic crimes. Hall (1978) and Gilroy (1982) claim high levels of criminality among ethnic minorities are mythical – an illusion caused by distorted media attention and inadequate official statistics. Gilroy also argues the over-representation of ethnic groups in the statistics is a result of selective police practice arising out of police racism. This is particularly true of young, working class African-Caribbean males. Lee and Young (1993) argue that increased levels of social deprivation and marginalisation explain the use of crime as a response to their situation. The official crime figures are used as a political weapon at times of economic or political crisis (Hall, 1978) – the myth of black street crime as a scapegoat to divert public attention away from the real social problems of unemployment, poverty. On this basis, ethnic crime (dominated by theft) is a political response to capitalism and racism, results from deprivation, racial disadvantage and discrimination, political exclusion, and distrust of/hostility towards the police, and is therefore a natural focus for police activity, especially where the police are white. Hence more resources are devoted to locating and recording ethnic crime.