Rhetoric and Power

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

Rhetoric and Power

The Power of Words in Shakespeare

In Timon of Athens, Coriolanus and Julius Caesar

The subject of the power of words within Shakespeare’s play is a colossal one, comprising of a multitude of aspect and even more examples. I shall therefore have to restrict myself within this essay, to avoid creating an overly-long ramble of tiresome and repetitive points. In order to be concise, I intend to examine three plays only; Timon of Athens , Coriolanus and Julius Caesar , in which I think the topic of rhetoric and power is particularly relevant. I shall look at two aspects within this; the power of words as they are used to affect characters and the power of words as they are used to affect the audience.

I shall first look at the way in which Shakespeare has characters influence each other through the use of rhetoric. Brutus, for example, uses the power of rhetoric to attempt to appease the upset

Romans by offering himself up to sacrifice in way of resolution to avenge Caesar’s death;

“With this I depart, that I slew

My best lover for the good of Rome, I have the same

dagger for myself, when it shall please my country to need my death.”

JC III.II 44-47

In offering himself in way of compensation for the loss of Caesar, Brutus is using the technique known as asphalia, which he employs for a mixture of two reasons. Firstly, he is perhaps genuinely sorry for having to murder his friend and secondly, he is attempting to show himself to the crowd as feeling remorseful in order to make them pity him, sympathise with him and

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns ultimately, choose not rebel against him for his actions. His attempt is a success, his words having great influence over the crowd who do indeed sympathise with him and cry out “Live Brutus, live, live,” III.II.48

.

Timon is rather more subtle in his manipulation of rhetoric and employs it in order to extract information from the abhorrent flatterers through lulling them into a false sense of security. He wishes to determine whether they have come to him because they have heard about his gold;

“Ay, you are honest men”

TOA V.I.62

“Y’are honest men; y’have heard that I have gold;

I am sure you have; speak truth, y’are honest men.”

TOA V.I.67-8

By repeatedly terming them honest men he subliminally assures them of his faith in their honesty

The second of his sentences is wrapped or ‘sandwiched’ in this pretense; both starting and ending with “y’are honest men”. This device is known as epanalepsis and is clearly effective as the painter, convinced of Timon’s trust in his character, then admits to having such knowledge “So it is said, my noble lord” TOA V.I.69

.

Portia in Julius Caesar is also seen to use rhetoric devices to great effect for the purpose of extracting information from her seemingly troubled husband, Brutus. She asks him what is amiss, to which she receives the reply “I am not well in health and that is all” JC II.I.265. Unconvinced by this feeble excuse, she proceeds to construct a brief argument; reminiscent of the logical reductio

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns ad absurdum form in which she shows that such ill health, combined with present actions, is contrary to his nature;

“What, is Brutus sick?

And will he steal out of his wholesome bed

To dare the vile contagion of the night?

And tempt the rheumy and unpurged air

To add unto his sickness? N o….” JC II.I.62-6

She states three questions for which, if she were to confirm a positive answer, she would have to concede her argument and admit that Brutus’ excuse stands solidly. If she did not provide an answer at all, the questions would remain up in the air, neither adding to nor detracting from her attack of Brutus’ reason. What she does do, however, is choose to answer them herself – a technique known as anthypophora. In answering her own questions in this negative way, she leaves no room for debate and deftly tightens her argument, soundly pointing out that Brutus would not act in such a way if, as he claims, he was indeed sick.

Portia’s attempt is as successful as that of Timon and Brutus therefore, eventually agrees to tell her the truth “Portia, go in a while,/

And by and by thy bosom shall partake/ The secrets of my heart.” The art of persuasion is certainly acknowledged as a powerful device in both Timon of Athens and Julius Caesar .

The power of persuasiveness is often particularly evident in plays in the instances in which a character attempts to turn a crowd or to boost the morale of an army, both of which appear within

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns these plays. Martius, for example, furiously rebukes his retreating troops with rhetorically-sculpted threats;

“Mend and charge home,

Or by the fires of heaven, I’ll leave the foe

And make my wars on you!” Coriolanus I.IV.39-41

His strict imperative is accompanied by an “astrothesian” oath sworn to the stars, for which he provides a vivid description “the fires of heaven” (a type of description known as astrothesia). His allusion to such seemingly untouchable and immovable objects reinforces the weight of his threat, which he portrays as immovable and wholly serious.

Coriolanus later becomes a victim to the art of persuasion as Brutus persuades the citizens that

Coriolanus is arrogant and despises the lower classes, making him unworthy for the role as consul. The citizens have given him their consent but Brutus accuses them, with the simple device of rhetorical questioning, of having made a severe mistake;

“…do you think

That his contempt shall not be bruising to you

When he hath power to crush? Why, had your bodies

No heart among you? Or had you tongues to cry

Against the relationship of judgment?” C II.III.187-91

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

Rhetorical questions are commonly found in a formation of three, which proves to be a fitting number as more than two produces listing, adding weight to the argument by implying the evidence is in abundance and four could perhaps lose the “punchy”, concise style with which a tight argument is often associated. These particular three succeed in arousing anger in the citizens who respond thus;

“THIRD CITIZEN

SECOND CITIZEN

He’s not confirmed. We may deny him yet.

And will deny him” C II.III.195-6

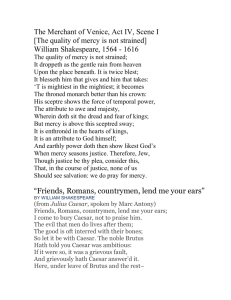

Clearly the power of words and their rhetoric use is valued within these plays as the plays exhibit various instances in which the characters achieve their desired response through the use of rhetoric. When Martius wanted his troops to fight, he did not start hitting them until they complied; nor did Timon torture the poet and the painter - or Portia wound Brutus in order to extract the information they desired. Shakespeare has opted for the power of words over the power of physical force in these cases. This does not mean that the art of rhetoric is not used in situations which more obviously call for words rather than physicality. On the contrary, rhetoric is used when characters decide to argue their point such as in the case of Anthony, who faces a crowd that admire and respect Brutus and to whom he will be delivering a speech based on opinions contrary to those held by the respected Brutus. He approaches the situation very delicately, constantly assuring the audience of his respect for their much-loved Brutus;

“Come I to speak in Caesar’s funeral.

He was my friend, faithful and just to me;

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

But Brutus says, he was ambitious,

And Brutus is an honourable man[…]

Caesar hath wept:

Ambition should be made of sterner stuff.

Yet Brutus says, he was ambitious,

And Brutus is an honourable man […]

I thrice presented him with a kingly crown,

Which he did thrice refuse. Was this ambition?

Yet Brutus says, he was ambitious,

And sure he is an honourable man.”

JC III.II.85-8, 92-5, 97-100

Anthony ventures to make a controversial statement about Caesar’s lack of ambition several times, but appears to undermine this by introducing Brutus’ opinion. Superficially, this appears to be the antithesis of commoratio – a technique in which one’s strongest argument is returned to, though in Anthony’s case it would seem that he wanders back to a generic statement that appears to undercut what he has just asserted. The technique that he is actually employing however, seems to be some form of quasi-paromologia. Paromologia is a rhetoric device in which one admits a weaker point in one’s argument in order to make a stronger one – in Anthony’s speech it is only “quasi”- paromologia as whether or not a point is weak in his particular argument is a matter of subjectivity. The crowd, who love and respect Brutus’ every word, would indeed see

Anthony’s assertions as being weakened by the fact that they contradict Brutus’ views. What

Anthony seeks to prove to them however, is that their common belief that “Brutus is an honourable

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns m an” is not necessarily true and even if it is, it does not exempt him from blame, nor mean that he was in anyway correct about Caesar being of an “ambitious” character. He almost mechanically repeats the phrase “But Brutus says, he was ambitious/ And Brutus is an honourable man” to the point that it sounds practiced and unnatural, in repeating it in this way, the statement becomes less and less convincing as he proceeds with the argument and thus, with a form of reversepsychology, does he convince the crow d not to believe Brutus’ terming of Caesar as an

“ambitious” man.

After having heard Anthony’s plea for Caesars innocence in the pursuit of ambition and then having been exposed to the sight of Caesar’s mauled corpse, the crowd take the lead of

Anthony’s command of language and use a technique of rhetoric to encourage themselves and each other to seek revenge. “Revenge! About! Seek! Burn! Fire! Kill! Slay!” they shout, using the fragmented, rushed speech of brachylogia, for which they choose only imperatives

– enthusing their cries with a bolstered sense of deliberation.

The power of words is further enhanced by the characters’ fear of them as Coriolanus, for example, judges words as more frightening than physical violence, “When blows have made me stay I fled from words” C II.II.66

. He exhibits an inclination to being presented with physical violence than to encountering a bombardment of words, suggesting that he feels more able to cope with fights than with words. Other characters also acknowledge quite openly the power of words and the effect they have on their fellow characters as Anthony notes “When Caesar says

‘Do this’, it is performed” JC I.II.10. Anthony recognises the power of Caesar commands and the respect and obedience they are given, a power that accompanies his words due perhaps to his

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns social status. Brutus also fearfully alludes to the powerful effects of words- in particular the strength of oaths “No, not an oath…do not stain/ The even virtue of our enterprise” JC II.I.13,131-

2 . He believes the words of oaths to be so powerful that they could potentially “stain” the “virtue” of his “enterprise”.

Despite the many examples of the powerful use of words having the desired effect on other characters, the art of rhetoric may also be seen to be lost on some. When Menenius, for example, attempts to persuade Coriolanus to forgive Rome and make peace, he pleads with him, hoping to offer him a preferable alternative to war, “O my son, my son! Thou art preparing fire for us; look thee, here’s water to quench it.” C V.II.67-8 . He uses repetition of “my son” in the hopes that this will appeal to Coriolanus’ emotions and persuade him to take act on the following advice. This technique was used in vain however, as Coriolanus merely responds with “Away!”. It cannot be said that Menenius’ words have no effect on him, however as Aufidius notes Coriolanus’ “constant temper”

V.II.88

, suggesting Menenius’ words challenged his will power.

Timon provides us with another instance in which an attempt at persuasion does not achieve what is hoped for. He endeavors to encourage thieves to continue to steal by attempting to justify thievery as natural;

“The sea’s a thief, whose liquid surge resolves

The moon into salt tears. The earth’s a thief,

That feeds and breeds by a composure stol’n

From gen’ral excrement…” TOA IV.III.32-5

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

Timon uses anaphora “The[…]/The” to create a listing effect, which implies that he is capable of giving numerous examples in which nature is seen to steal, thus bolstering his argument. He invokes natural elements and objects “The sun”, “The moon”, “The earth”, in order to prove that thievery is fundamentally natural. His powers of persuasion, however, achieve the opposite affect to that which he was seeking as the thieves are in fact persuaded to leave their life of robbery;

“THIRD BANDIT persuading me to it

FIRST BANDIT

H’as almost charmed me from my profession, by

‘Tis in the malice of mankind that he thus advises us,

Not to have us thrive in our mystery.

SECOND BANDIT I’ll believe him as an enemy, and give over my trade.”

TOA IV.III.443-7

It could be argued that his rhetoric is in fact not at all powerful as it results in the thieves acting oppositely to what Timon attempts o encourage. This could be viewed another way, however, as although they are not persuaded to pursue the life of a thief, they are still influenced by his words to such an extent that they act due to them. This interpretation would allow the art of rhetoric to remain powerful, but suggest that an incorrect use of it perhaps – as in Timon’s case he is motivated out of a hatred that blinds his reasoning and perhaps also his speech – would result in a consequence different to that for which one originally sought.

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

There are other cases in which rhetoric fails to achieve what the character desired. The words of the poet in Timon of Athens , for example , are somewhat lost on his fellow painter, who finds the flowery rhetoric incomprehensible and asks “How shall I understand you?” I.I.52

. Apemantus is equally unimpressed by poetry and finds no power in the poet words as he believes they are lies as to be a poet, “thou liest” I.I.217

. Shakespeare has Apemantus adopt the view that poets are liars; a view stated by Plato in REPUBLIC 10 “The imitative poet […] is an image maker, far removed indeed from the truth”, a view which was later promoted in Stephen Gosson’s The

School of Abuse (1579?). Such a view would suggest that the power of rhetoric is irrelevant as rhetoric in any form of poetry is a sinful lie. This absurd view was countered most aptly by Sir

Philip Sidney, who responded “Now, for the Poet, he nothing affirmes, and therefore never lyeth.

For, as I take it, to lye is to affirme that to be true which is false”

An Apologie for Poetrie (early

1580’s). It is likely that Shakespeare would have come across this response and that Apemantus’ terming of a poet as a liar due to his imitative language derived from a weak argument that had never recovered from its criticism. We cannot view Apemantus’ opinion therefore, as a valid criticism of the power of rhetoric as it is clearly flawed, a fact of which Shakespeare is most likely to have been aware.

It can be seen, then, that within the plays, rhetoric can be highly powerful, though it is not always used so and depends of cour se upon Shakespeare’s decision. As the playwright, he determines the response of each character to each use of persuasive language and the fact that there are numerous instances in which language is shown to be particularly influential, proves that the relationship between rhetoric and power is an important aspect within these three plays.

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

Up to this point, I have now only covered one of two aspects of rhetoric and power within

Shakespeare plays, the second, which is at least as important as the first, is the way in which rhetoric may persuade the audience to imagine the scenario that Shakespeare intended to create on stage. This power does not extend to them believing in the play because as Dr Johnson quite rightly said, “The delight of tragedy proceeds from our consciousness of fiction; if we thought murders and treasons real, they would please no more.” The Plays of William Shakespeare (1765)

We can only assume, therefore, that what Shakespeare sought to achieve with his use of rhetoric with regards to the audience, was to aid them in their imagining of the hypothetical situation that he presents them with, in the way that he wanted them to see it. For example, when alone in the woods Timon expresses his hatred for all humans, wishing plagues upon them;

“Plagues incident to men,

Your potent and infectious fevers heap

On Athens ripe for stroke! Thou cold sciatica,

Cripple our senators, that their limbs may halt

As lamely as their manners!” TOA IV.I.21-5

This exclamation arises from deep indignation; a hate for the human race that has been brought on by a realis ation of the fickle nature of his ‘friends’, who were in fact only his flatterers. This exclamation is an example of a rhetoric device known as aganactesis, in which, for this particular usage of it, he cruelly and bitterly wishes ill fortune on all. The technique is used to convince the audience of his acute anger and his intense hatred of all mankind, which enables them to

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns understand his reasoning behind later actions, such as turning away Alcibiades, who offers him help.

Shakespeare employs the power of rhetoric in an even subtler manner when he silently requests the audience to imagine the setting in which he has placed his characters. For example, in a conversation between Apemantus and Timon, in which Apemantus asks Timon what he would

“have to Athens”, Timon responds;

“Thee thither in a whirlwind. If thou wilt

Tell the, there I have gold; look so I have.” TOA IV.III.295-6

By using the two deictic terms “thither” and “there” – Shakespeare has the audience imagine great distances, encouraging them to conceive of a forest in which Timon resides, which is far from

Athens. Apemantus is used for the same purpose slightly later, when he comments “Yonder comes a poet and a painter” IV.III.439.

“Yonder” is an extreme distal demonstrative adjective, which has been cleverly inserted here to encourage the audience to think beyond the walls of the theatre and imagine two characters walking from far away. It seems that Shakespeare’s use of rhetoric for the audience is often far more subtle that that used within his plays, character to character, perhaps because he has control over the characters ’ responses but obviously cannot govern the audience in such a way and therefore he merely endeavors to encourage them, in a discreet manner, to conceive the play in that way that he wishes them to.

November 2005

Dr Hartle Rachel Burns

Although there are several instances in which Shakespeare chooses not to display rhetoric as powerful, there are many examples in which the power of words is depicted as a greatly influential force. There are, of course, many more examples of rhetoric in which it is shown as powerful or ineffective, but I feel I have sufficient evidence to conclude that there is undoubtedly a strong and obvious relation between rhetoric and power in Timon of Athens , Coriolanus and Julius Caesar .

November 2005