Social model and educational ethos: A possible conflict in education

advertisement

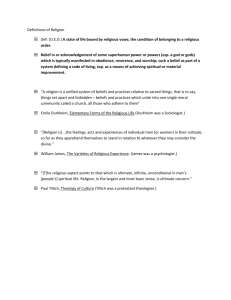

Social model and educational ethos: A possible conflict in education for citizenship Alfredo Rodríguez Sedano Universidad de Navarra arsedano@unav.es Aurora Bernal Martínez de Soria Universidad de Navarra abernal@unav.es Miguel Rumayor Fernández Universidad Panamericana mrumayor@up.mx Summary: This article endeavours to approach education for citizenship from a social perspective. This requires, firstly, reference to the civilization in question, to the kind of society dealt with and its foundations. Next, attention is paid to the educator. Could one count on a teaching ethos that offer a response to the educator needs of an education for citizenship? With regard to the educated, the attitudes that should be encouraged for such an education to be effective are emphasized. Both proposals establish guidelines for the development of a curriculum in education for citizenship. Key Words: social model, ethos, education for citizenship, virtues, profession. 1 1. Introduction In order to approach education for citizenship, civic, moral and political education, it is firstly necessary to make reference to the civilization that we are dealing with, an idea about what type of society we are speaking of and what its foundations are. If we clarify this relationship then we will be able to establish guidelines and proposals that facilitate the development of civic education for the citizen of the 21st century. In spite of the abundant literature that appears when we are thinking about this question, we can affirm that after a century there have been no substantial new features in this theoretical scope. The social convulsions that determined the 20th century and the new ones that we are facing nowadays undoubtedly make it necessary to formulate again what type of citizen our society needs. Yes, it can be affirmed that behind those convulsions there is a hidden failure to which we must pay attention: the conception of citizen that is supported by the prevailing social model. Thus it seems pertinent that we initially reflect on the social model that maintains this type of citizen. However, if we want to give an answer to the type of citizen that our society demands, we have to pay attention to who educates. In this sense, we will highlight the most relevant attitudes needed to practice that type of education. In other words, to see if it is possible to have an educational ethos that is able to give an answer to the educational necessities of education for citizenship as well as to the person who is being educated. In this sense can be underlined the attitudes that we must foster among the students in order to obtain this type of education. Let’s start by reflecting upon the prevailing social model. 2 2. The pluralist society The plurality of society is an undeniable fact. Another question is to speak of a plural society with the nuances introduced with respect to this social fact. If we focus on western society the proposals on the social model keep, with some shades, certain types of similarities. Nowadays the idea of a pluralistic society is commonly admitted; this fact is a way to give an answer to so many questions that appear and has as a purpose to preserve the social cohesion of a world which has become more globalized. Giovanni Sartori´s concept (2000) could be an interesting example of a plural society. His thesis basically consists of a plural society departing from Popper´s vision but limited. This is a plural society based on integration, therefore plural, nonetheless fighting against multiculturalism, which he considers the negation of pluralism. Sartori considers integration the necessity of sharing ethics and political values of our western civilization. Thus he demands a strong component of adaptation and socialization. In this way, integration is a mechanism for facilitating and controlling the loyalty of a new citizen. It brings strong moral power that helps the citizen of this society to survive and flourish. Is this contribution new? Tracking the authors who have thought more about this question we can turn our sight to Emile Durkheim, and find that in the moral constitution of society that he supported this idea already existed. As Ceri indicates (1993, p. 143) "regulation and integration are the two basic structural variables of the durkheimiam system for explaining social action". Indeed this conceptual tool -the distinction between integration and regulation has its total development in the work The Suicide (Múgica 2004, p. 96). 3 This conceptual tool is necessary to solve the problem that arises with that which Durkheim calls the egoistic anomie. It is anomie that indicates the lack of regulation of the modern social system. "If the division of work does not produce solidarity, it is that the relationships between organs are not regulated, they are in a state of anomie", (Durkheim, 1986, p. 360; see also, Ramos Torre 1999, p. 45). This worry, caused by the lack of regulation of the modern social system, was already in Durkheim’s works previous to The Suicide. It is enough to recall Durkheim’s refusal to consider the obligatory nature of moral based on unattainable and unreachable moral ideals as he had learned from Wundt. The possible happiness that might come from that is a moral ideal which is full of sadness (Durkheim 1887, p. 141; and Durkheim, 1928, p. 291). Thus moral did not reach its high priority function which is no other than its mandatory character, therefore regulation would not be possible. Durkheim underlines this idea with his critique toward utilitarianism, proposing a coercive and sociological concept of morality (Durkheim 1886, p. 207). He is advancing the features that must characterize the moral fact: authority and obligation, making possible those moral acts as elements of a regulation. In Durkheim civilization, citizenship or moral education and political education are terms assimilated among each other. If we continue tracking the thinkers who came to perceive society this way, the social model and human conduct insofar as it is social, it cannot be ignored that Durkheim has a great debt to Comte, although he separated from some of his points. Nevertheless, Durkheim finds in that author an idea that is going to allow all the sociology that came later to develop: social solidarity, Humanity. 4 Positivism offers a new perspective to the modern man on his understanding of society as well as the problems that surround him. The social thing is for Comte the supreme category where every other acquires sense and concretion. Positive philosophy, being understood as a public reason, is the only possible exit to the crisis that his time suffers and is the only basis for moral (Zubiri 1997, p. 147). These are the foundations of the moral constitution of society, as well as the later development of the model of pluralistic society based on these concepts. Relativism found in positivism its source of expansion. 3. The limits of the pluralistic model of society We consider that from these models, as mentioned above, it is impossible to obtain a neat model of education for the citizen of the 21st century. This problem comes, as Bernal posits (2005), from the confusion between socialization and sociability. Socialization is an important dimension of the educated but it is incomplete if we don’t deal with sociability. Sociability makes reference in a direct way to the social education of the human being, whereas socialization makes reference to the incidence of the environment in which he develops. Both concepts cannot be separated from the unity of person. This is the reason why we must treat them together (Rodriguez, Bernal and Urpí 2005). Continuing with this distinction, Durkheim (1996, p. 50) understands socialization as the external element that influences the student, while García Garrido (1971, p. 106) affirms sociability as the quality of the human being in order to be present in society and to reach social maturity and consequently the growth of personality. 5 Nonetheless, the educator has to deal with both aspects. In order to accomplish this exciting task, he has to have a clear idea of human being (sociability) as well as of the social environment which surrounds the student (socialization). If we contemplate education for citizenship only from the point of view of socialization we are disregarding the inner energies coming from the human nature of each student. This is the proper movement, from the internal to the external. In this way an abstract concept of socialization implies limits (Rodríguez, Bernal, Urpí, 2005). Also, this is the main difficulty the pluralistic model of society, which is based on socialization – integration as a way of controlling– that could lose the wealth of the nourishment of human qualities in reference to the origin. Likewise, there is a similar problem if we only consider sociability. It is not possible to reach full human flourishing and human maturity without taking into account the social environment. In this light, both concepts also show that education for citizenship is not an egalitarian process insofar as we educate non-equal citizens, the diverse environments and classical social virtues work together. Through sociability and socialization, as well as solidarity, we learn to be good citizens (Delors 1996). Another important reason that we suggest to demonstrate the limits of the pluralistic society is the historical ideological origin which the concept of solidarity is based on. The French word egalité means equality in everything, in every aspect of human being included morality. This means that every use of liberty is legitimated insofar as is coming from an autonomous will; the only condition is that the self is choosing (Bloom 1989, p. 148). From this last stance about equality, the State is the main protagonist of the social life in front of the citizen. In a pluralistic society the State is not just the guarantee of rights 6 and deeds of the citizen but it is also the guarantee of citizenship as well as the model of citizen. Taylor criticizes this idea commenting that the efficiency of social life is simply supported on the structural efficiency of the official institution of the State (Taylor 1994, p. 86). According to Thomas Aquinas’s thesis (Suma Teológica, I-II q. 96, a.2.) the State must only rule those acts belonging to Common Good. This is often seen as a contradiction for the ruler’s attitude since “in order to avoid removing someone`s liberty of abusing his/her own liberty, he, the ruler, should give up his own freedom to punish those behaviors that are negative for the civil society, in particular, those behaviors that highly affect the effective use of liberty by those who do not want to use their liberty badly (Millán Puelles, 1995). We are saying that the constitution of the modern vision of citizen is located, among others, in Durkheim, Comte, Sartori; nonetheless, maybe the most important doctrinal basis are Machiavelli and Luther. As Velarde posits (1986, 144-145), “both doctrines complement the same thesis. Human acts are neither good nor bad –Machiavelli affirms– rather, they are good or bad insofar as they are done for the benefit of the State. On the other hand Luther says that the feeling of guilt is useless: the malice of an act consists of regarding it as bad or good. In this way he postulates, without rational foundation the ideological thesis that constitutes the substratum of modern political thought, which liberates from responsibility the modern subject (Luther) and the objective (Machiavelli). Machiavellism was really an invitation to discover valuable goals that justify every human appetite; Lutheranism, on the other hand, was an invitation to be free from the guilt feelings that come from following those appetites”. 7 In contrast to the last concept, a moral education entails an education for the practice, and is not simply a theoretical issue (Nich. Eth., II, 2, 1103b, 27-29). According to this way of looking at ethics, virtue is manifested as far as we act. It is then that the human being unveils what she is. In other words, education for citizenship is a question of a tangible liberty which is proven in the existence of virtues. 4. The education of citizenship: a question of liberty According to what we said, the revitalization of the immanent action –to do– in the educational act and in education in general is a crucial element for an adequate education for citizenship. In the recommendation presented by the International Commission for the Education in the 21st Century, organized by the UN, which resulted in Delors’s famous report (1996, p.33), we can find the basis for the development of civic education. This report affirms that the educational system must advance in order to give an education founded on these four pillars: Learning to know, Learning to do, Learning to live together, Learning to be. Clearly this report underlines: “its recommendations are still very relevant, for in the twenty first century everyone will need to exercise greater independence and judgement combined with a stronger sense of personal responsibility for the attainment of common goals” Delors (1996, p. 21). These recommendations are not partial goals; rather they are several dimensions of the ultimate goal of education (Altarejos y Naval 2004). They also mean that we cannot 8 exclusively foster abilities and skills but we need a deep personal implication both for educator and for the educated. The task of the docent, according to the indicated recommendations, is not just an action of knowing things but knowing how to act in sciences and life. Both kind of knowledge have to be communicated (Altarejos y Naval 2004) to the student, since they are the best help that the student could receive for achievement, both for the personal implication and for the final goal of education. This personal implication can only be appreciated when education is basically an assisting task, where the help given is greater than mere service. The difference between both notions seems very important in order to learn that education for citizenship is something related to liberty (Mauro y Rodríguez 2005). We want to highlight this idea of helping because the notion of service has greatly contributed to the transformation of professions. Nonetheless both elements are clearly different. If we consider the teaching work as help, this much better reflects what we want to do and also the main sense of the action: to lead someone, the educated, to reach by herself her own goal. As Altarejos says “there is a neat conceptual difference between servicing and helping related to finality (…) In servicing the taker is someone who takes the good; thus she is a passive receptor. Nevertheless, in helping, the receptor is someone who is reinforced by her own action, the reinforcement precisely is the good which is offered; here the helped is an active agent” (2003, p. 43). We can say that the teaching task consists of helping students to search; teaching students how to search, also teaching them an intense search for good. The capacity of the educated for searching is shown in his liberty of destiny; insofar as this liberty allows us to 9 guide them from the openness of the native liberty, this fact provokes in the student the encounter with the desired truth (Polo 1999, p. 236). Through the learning process the student finds, at the same time, the truth and how to reach it. Once the truth is partially reached the next step would be a new searching process: the intensification of that truth. This is how the docent helps the student reinforce her action. Help understood in this way is consistent, from liberty, with the finality of education: acting for happiness. According to this form of understanding education for citizenship it is necessary that we stop for a moment at the professional ethos that appears with every educator (McLaughlin, 2005). We discover that the present characteristics that appear nowadays with that concrete ethos perhaps are not the best in order to develop the educative action. Therefore, it is relevant that we, as Altarejos affirms (2003, pp. 87-119), define some ethical qualities in order to present an ethos which would harmoniously fit with the assisting character of education that we are speaking of. 5. The professional ethos of the educator We will start by reflecting upon the commonly and accepted diverse notes that are part of the educational work and reflect on the assisting character of education. We want to suggest the ethical qualities that exist in the docent task as well as show the concrete ethical qualities that every educator must feed in order to bring about an efficient and effective education for citizenship. 10 5.1. Notes and characteristics of the profession There were many attempts, from different points of view, to clarify the professional task of the educator (Woethigton, 2003, Higgs, 2003, Barber, 1995, Carr, 200). Maybe one of the most interesting of these attempts, in order to shed light upon the way of exercising education as well as in order to recover this professional activity, was made by W. Carr and S. Kemmis (1988, p. 26) (Altarejos, 2003b, pp. 19-50; and Rodríguez, Altarejos, Bernal, 2005). These authors reduce professionalism to three different features: a. knowledge based on theoretical learning b. subordination of the professional to the interest and welfare of the client c. right to make autonomous judgments free from extra-professional control If we refer these features to the educational task, we have to consider our analysis in order to have an adequate conception of the professional docent. a. Knowledge based on a theoretical learning It seems clear that any practical knowledge can be considered as a group of skills, abilities derived from a theoretical knowledge. We can affirm that even with a complete knowledge of the human condition and its way of acting, if this were possible, we could not help the student in his improvement in each single case. In the educational scope we learn as far as we act, and we learn to teach by teaching, not simply by knowing the essence of education or nature or the educated (Alvira, 1988). 11 In the interaction that is done in education appears freedom that allows us to discover the novelty in every action. The key point is discovering that in education we are working with persons (Alvira 1985, p. 8). This dimension of freedom makes it easy to see the stimulating part of education: every person gives us always something new due to the uniqueness of the person. It is impossible to formalize every situation of human being. In regards to education, we never educate people to set them free, but we educate those who are already free in order to make good use of liberty. This idea of education brings us directly to the practical dimension of learning. As we are saying, education for citizenship is not merely the recognition of the ideal of good citizen but we have to learn how to do it in the practical action. b. Subordination of the professional to the interest and welfare of the client In this second characteristic a key factor is the servicing capacity given to the client (Shaney, Banwet, Karunes, 2004). In this way, at least as a generic formulation, it does not raise any doubt. Nonetheless, if we deal with this element in the educational world the formulation turns into a problematic issue. Who is the client in education? What are the products? What are the benefits? The most common answer is to observe the educated as a client (Constanti, Gibbs, 2004, p. 44). Nevertheless, even accepting this premise, in this response we have to underline the peculiarity of this type of client. This originality comes from some pedagogical circumstances that we want to clarify. For instance, in any other professional scope we can foresee the negative consequences of the possible failure of a product or an action. Then we must notify the client about that. Is it possible to give this information to the student? Is it possible to announce our failure or hers in the educational task? 12 Maybe from a consumerist point of view this could be possible, but not from the educational perspective. Perhaps sociologically it would seem through the use of prospective work, but when we are dealing with an ambit where liberty is the main element involved, then this attempt, for its radical inconsistency (Polo 2001, p. 57), is totally useless. This last conclusion makes us consider a very relevant aspect of education for citizenship: blindly trusting in the goodness of curricula does not assure it will be successful. We need to be ethical in every single action. c. Right to make autonomous judgments free from extra-professional control. This may be the most problematic aspect for the professional of education (Carr y Kemmis 1988, p. 27). “There is the conflict between a goal of independence for the learner and his unavoidable dependence on authorities for information and guidance if he is to advance in knowledge beyond the level of a child without language” (Lewis, 1978, p. 154). Nevertheless there is another type of autonomy which is reachable. In education, no matter how similar, there are no global solutions to singular problems. The educator would take into account those persons that are present, trying to adapt learning to the necessities of each one. The intentionality of education that goes with teaching makes it impossible to give formation in advance, ignoring the worries and necessities of the receptor. Let’s think for a moment about two people with drug addiction problems. Is it possible to establish the same procedure when social circumstances, the culture, the family environment, etc. are 13 completely dissimilar? One more time, personalization of the solution brings us to learn that the educational task is practical and personalized in every concrete situation. Perhaps autonomy, of the three explained characteristics, is that which more unanimously defines the profession. It helps us to distinguish it from any other occupational task. This characteristic makes simultaneous reference on one hand to the personal capacity of taking operational decisions at work, in spite of any external pretension, as well point out the pertinent social responsibility in from of results and the quality of the work. Day to day work demands more interactions, the exigency of interdependency reclaims more interactions. That mentioned exigency is clearly visible in the education of citizenship where theoretical and practical knowledge are merging. Analyzing these characteristics, it seems proper that we focus on the profession of education highlighting its assisting feature. 5.2 Ethical qualities of ethos as assisting profession We must underline help as the method that makes every educational process efficient. Insofar as help introduces us in every educational work we can understand that education is basically an assisting work: we must assist, help others, and teach those who need it to find the truth. But that search, encounter and success, is only possible for those who are facing the truth, that is to say, the educated. 14 Nonetheless, taking into account professional educational tasks as well as the notion of help that goes with this task, we can distinguish five elements that allow us to identify the professional of education (Altarejos 2003, pp. 42-45): competence, initiatives, responsibilities, commitments and dedication. The understanding of these characteristics allows us to discover the true agents of the educational process and the subsidiary role of the State. a) Competence Competence is related to the personal skill in solving and facing one’s own problems of education for citizenship. It is knowing how to do and make as well as how to face the complexity of the elements (Altarejos 2003, p. 44; Rudduck, Berry, Brown, Frost, 2000). The professional of education through the help of his competence achieves a real worry and true benefit for the other. Here is the cornerstone of what Álvaro D’ors (1968, p. 10) calls the Autoridad (authority as a power) which is totally different from the Potestad (authority as a prestige). This latter authority is a socially valued issue, reinforced and supported by another’s action. This is precisely the help that we give from an educational profession with an assisting nuance. The task of helping demands a mutual affective relation between the docent and the student which is not the only basis for education but a valuable and efficient element in the assisting work. That is the mark given by the teacher upon the student and it is a very important element for acting with happiness. 15 b) Commitment Competence is not possible without the personal commitment of the docent. This commitment is by its nature basically a non objective and classifiable element: a commitment is something located in the personal conscience, the only real place where someone is involved in a concrete action. This gives that action a dimension that goes much further from what we might stipulate in a contract. Commitment sheds light on and pushes forward the rest of the educational elements. From this characteristic we can speak about professional excellence which is inscribed in a subjective dimension of work rather than an objective one, and it is deeply linked to the idea of being a good citizen. Commitment entails overflowing the objective dimension, overcoming the sole productive efficiency insofar as the assisting character inherent to the profession is rescued (Polo 1996, p. 107). c) Initiative According to what we are commenting the educational profession is located in an innovative perspective, as far as the commitment of the educator is not objective it goes further from a strict occupation. Also from this perspective, initiative is not only a condition of work rather it is an exigency on whom is working. The subjective dimension of working supports these characteristics. Therefore here the only way of progressing is by the personal 16 help of that novelty that everyone provides though his actions. This aspect rejects the standardisation and unification of the educational task. Educational work is understood as a personal vocation that entails a response according to the personal commitment. This would further expand the goal of the task ending when we reach what we were looking for. Thus, this endeavour involves not only the work done but the personal growth of those who are in the process. That is to say, the práxical and poiétical dimension of action (Nich. Eth., VI, 4, 1140b). In doing so, we can say that in the profession of teaching there is a process of decision where the subject is not just deciding upon the object but upon himself, therefore the action is not only poíesis – teaching- but truly educational action (Altarejos, Rodríguez, Fontrodona, 2003c, pp. 94-95). When the educated acts civically them he becomes a citizen. d) Dedication We define dedication as the human attitude based on self-giving, assignment, offering. Dedication is much more that to occupy oneself in an issue; it consists of a personal commitment. The difference between dedication and occupation can also be appreciated in components like intensity of implication and quality of dedication, whereas a simple implication is more measurable and extensional. Nowadays from this point of view we can affirm that the professional of education tends more to occupation than dedication. On the 17 other hand, if we consider the time factor, we can say that dedication is not related to the invested number of hours but rather to the full disposition of the subject. In this way, occupation is seen as an enormous investment of time but with a lack of personal responsibility, jumping from one task to another. The most abstract fields, as civic education is, are marginalized insofar as they are always understood with “lack of time”. Dedication is obviously internally connected with help. Seeing others as neighbours reclaims for the educator a permanent attitude or disposition in front of the upcoming necessities in the student. Say that dedication it is not a question of offering a service in front of the necessities of the student, rather of being accessible in order to give help; all the time reinforcing the action of the other. It is an implicit commitment as far as there is not a suitable objectivation action; it is to understand the profession as a permanent calling that demands a response. Exercising this characteristic is only possible through the liberty of those who are involved rather than through the external imposition of the procedures. The diverse attitudes that the State would adopt will foster occupation or dedication. c) Responsibility Responsibility is an important note that appears as a fruit of the characteristics that we are touching on. It is not possible to speak about the rest of the things if we do not “take charge”. With responsibility we are highlighting the communitarian character that comes with the professional task. In other words, what Donati (1998, pp. 46-56) calls relational paradigm (Donati 1991), which at the end of the day is a crucial element for the 18 educational task. To “take charge” in this way means to consider others in themselves that help in order to create the we. Then, responsibility entails an obligation of the subject of taking it, looking for the best action, in order to reach beneficial actions for growth, for one and for others (Altarejos 2003, pp. 45-46). From responsibility the professional of education is called to a permanent education, that would improve his competence, facilitating initiative, making efficient his dedication and commitment. In this way the increment of liberty in education is what directly increases the bettering of the educational quality. Responsibility is moral a quality in itself. It is the foundation and reason for the assisting professions. In many ways the assisting character is behind every human work but mainly in those like education whose finality is directly based on its assisting character. 6. The fundaments for an education of citizens We have said that speaking about education, as a question of liberty, it is very important that finality cannot be promoted from the scope of abilities and skills (procedures) rather we need a deep personal implication both for the educator and the educated (Altarejos, Rodríguez, Fontrodona 2003c, p. 190). A good education for citizens must continuously regard breadth and continuity of solidarity actions. These actions must be fostered from the development of human 19 sociability. This is a condition for creating a habit; otherwise we might create occasional acts of solidarity and good civic behaviour where the personal implication is absent. We want to emphasize that in education for citizenship the main issue is to achieve a communitarian action based on social self-giving, personal donation: giving by accepting and accepting by giving (Altarejos, Rodríguez, Fontrodona 2003c, p. 191). This last idea demands the formation of certain habits that correspond to classical social virtues (Nich. Eth. Libro IV, y Summa Theologica, II-II, qq. 101-109). These virtues simultaneously achieve optimization of natural social tendencies and the birth of the education for citizenship, insofar as they express the giving-receiving dynamism of daily social life (for the present exposition, Altarejos, Rodríguez and Fontrodona 2003c, p. 192196; Choza 1981, pp. 17-74). Those virtues are the following: . Piety, which is the optimal reference to self origin. This is manifested by respect to fatherland, parents and God. The increasing extension of racism and xenophobia is provoked by the absence of these virtues in our western societies. . Honour. It is related to “brightness of virtue”. It consists of honouring and accepting the eminency of others as well demanding they be truly coherent with their actions. The loss of this social virtue is a sign of the ethical decline of society. It has elicited emptiness at the order of finalities. 20 . Observance. It is the virtuous tendency of keeping what is really valuable, above all, what is given by our previous generations. Due to the lack of observance there is a disregard for tradition, social heritage and culture. . Obedience. It responds to the tendency of obeying the legitimate authority. The absence of obedience provokes a weakening of the necessary social relations at the core of a community. Obedience supposes accepting who is commanding in himself. This is an efficient means of social cohesion. Occasionally what is mandatory is unjust; here the right conduct is to disobey. Nevertheless this situation is accidental: if we constantly refuse to obey social disintegration is coming. . Gratitude. The recognition and the acceptance of another’s act is for me an expression of the maximum degree of liberty. To give thanks is not an obligation but a very important social element. Therefore not having the habit of giving thanks is evidence of a limited liberty. . Vindication. It is the virtue that impels us to fix the received evil. It is distinguished from the vengeance which is the will to pay back evil with another evil. A real Vindication demands the reparation of received evil which is the restitution of the seized or damaged good. It is distinctive of vindication to reclaim what is my own or the rights that I have. . Veracity. It is the virtue through which we say what we really think and feel: through which we socially manifest who we are. The perversion of veracity is the 21 habit of hiding and silencing the truth according to our own interests. Another vice in opposition to veracity is a constant tendency to manifest oneself according to what the others expect, trying to please them. This is also a conduct that directly attempts against honour. . Affability. This is the virtuous tendency of giving what you have and are: it is the daily realization of the self-giving attitude. Basically it consists of learning to listen and the disposition of understanding the other. . Liberality. It is the virtue of ceding and giving what you have: both material and spiritual goods, for instance, sharing my time and my knowledge. As a social virtue liberality embraces more than justice, since we can give more than is strictly legal. To give freely is related to the affection of sharing things and possessions, and it is also related to solidarity. 22 Conclusions Education for citizenship is an education for people in a social context. In this way we highlight the moral character of the actions and therefore the importance of doing over acting. We don’t have to disregard acting in our day to day technical society which is sometimes relativist and without universal values. It is very important that we perceive the assisting character that entails the profession and underline the help which is given by every educational action. In fact, we could say that there is no a real service without help, otherwise we are speaking about unreal references of satisfaction of real necessities. These issues bring us to insist on two important aspects in education for citizenship. On one hand the ethical qualities of educator and on the other fostering virtues. These are the two columns where the educational curriculum rests. Therefore we need to develop the agents involved in education, the educated and the educator, the primacy are people, but not forgetting the social context. In this way is at stake that education for citizenship is a question of liberty and dialogue. This is a free dialogue without external and social control. The goal of social dialogue is not consensus but rather an understanding and acceptance of the other and the search for the truth. It is the acceptance of the other as a person by recognition of his dignity which does not necessarily entail the acceptance of his ideas. Dialogue essentially means, listening and understanding more than yielding 23 References ALTAREJOS, F., NAVAL, C (2004) Filosofía de la educación, (Pamplona, Eunsa). ALTAREJOS, F. (2002) Dimensión ética de la educación, (Pamplona, Eunsa). ALTAREJOS, F (2003a) El ethos docente: una propuesta deontológica, en VV:AA., Ética docente, (2ª ed), (Barcelona, Ariel). ALTAREJOS, F. (2003b) “La docencia como profesión asistencial”, en VV:AA., Ética docente, (2ª ed), (Barelona, Ariel). ALTAREJOS, F., RODRÍGUEZ, A., FONTRODONA, J. (2003c) Retos educativos de la globalización. Hacia una sociedad solidaria, (Pamplona, Eunsa). ALVIRA, T. (1985) Calidad del profesor: calidad de educación, (Madrid, Dossat). ALVIRA, R. (1988) Reivindicación de la voluntad, (Pamplona, Eunsa). ARISTOTLE (1976) The Ethics of Aristotle. The Nicomachean Ethics (revised edition) (London, Penguin Books). BARBER, M. (1995) Reconstructing the Teaching Profession, Journal of Education for Teaching: International Research and Pedagogy, 21, (1), 75-86. BERNAL, A, (ed) (2005), La familia como ámbito educativo, (Madrid, Rialp). BLOOM, A (1989) El cierre de la mente moderna, (Barcelona, Plaza & Janes). CARR, D. (2000) Education, Profession and Culture: Some Conceptual Questions, British Journal of Educational Studies, 48, (3), 248-268. CARR, W. y KEMMIS, S. (1988) Teoría crítica de la enseñanza, (Barcelona, Martínez Roca). CERI, P. (1993) Durkheim on social action, en S.P. TURNER, Emile Durkheim. Sociologist and moralist, (London, Routledge). CHOZA, J. (1981), Ética y Política: un enfoque antropológico, en AA.VV., Ética y Política en la sociedad democrática, (Madrid, Espasa Calpe). CONSTANTI, P., GIBBS, P., Higher education teachers and emotional labour, International Journal of Educational Management, Volume 18, Number 4 (April 01, 2004), pp. 243-249. DONATI, P. (1998) Il principio di sussidiarietà e il nexo famiglia-scuola, en VV.AA. Sussidiarietà e nuovi orizzonti educativi: una sfida per il rapporto famiglia-scuola, (Brescia, La Scuola). DONATI, P. (1991) Teoria relazionale della società, (Milano, Angeli). D’ORS, A. (1986) Derecho Privado romano, (Pamplona, Eunsa). DELORS, J. (1996) Learning: the treasure within, (Paris, UNESCO) DURKHEIM, E. (1887) La science positive de la morale en Allemagne, Revue philosophique, 1887 (24), 33-58. DURKHEIM, E. (1886) Les Études de science sociale, Revue philosophique, (22), 61-80 . 24 DURKHEIM, E. (1928) Le Socialisme. Sa définition, ses débuts, la doctrine saint-simonienne, (Paris, Alcan). DURKHEIM, E (1986) De la division du travail social, (París, P.U.F.). DURKHEIM, E. (1996) Educación y Sociología, (Barcelona, Península). GARCÍA GARRIDO, J.L. (1971) Los fundamentos de la educación social, (Madrid, EMESA). LEWIS, H. (1978) A teacher's reflections on autonomy, Studies in Higher Education, 3, (2), 149-160. McLAUGHLIN, T. (2005) The educative importance of ethos, British Journal of Educational Studies, 53, (3), 306-325. MAURO, M., RODRÍGUEZ, A. (2005) La educación: una cuestión de libertad, en Estudios sobre Educación, (8), 7-30. MILLÁN PUELLES, A (1995) El valor de la libertad, (Madrid, Rialp). MILLER, Th. K. and PRINCE, Judith S. (1976) The Future of Student Affairs: a Guide to Student Development for Tomorrow's Higher Education (San Francisco, Jossey-Bass). MUGICA, F. (2004 Emile Durkheim. Civilización y División del trabajo (I). Ciencia social y reforma moral, (Pamplona, Cuadernos de Anuario Filosófico: Serie Clásicos de la Sociología n. 11). POLO, L. (1996) Sobre la existencia cristiana, (Pamplona, Eunsa). POLO, L. (1999) Antropología Trascendental I. La persona humana, (Pamplona, Eunsa). POLO, L. (2001) Nominalismo, idealismo y realismo, (3ª ed), (Pamplona, Eunsa). RAMOS TORRE, R. (1999) La sociología de Émile Durkheim: patología social, tiempo, religión, (Madrid, CIS: Siglo XXI). RODRÍGUEZ, A., ALTAREJOS, F., BERNAL, A. (2005) La familia, ámbito germinal de la humanización del trabajo en II Simposio europeo dei docenti universitari, Roma. RODRÍGUEZ, A., BERNAL, A., URPÍ, C. (2005) Retos de la educación social, (Pamplona, Eunate). RUDDUCK, J., BERRY, M., BROWN, N., FROST, D. (2000) Schools learning from other schools: cooperation in a climate of competition, Research Papers in Education, 15, (3), 259-274. SAHNEY, S., BANWET, D.K., KARUNES, S. (2004) Conceptualizing total quality management in higher education, The TQM Magazine, 16, (2), 145-159. SARTORI, G. (2000) Pluralismo, Multiculturalismo e Estranei: Saggio sulla Società Multietnica , (Milano: Rizzoli) TAYLOR, Ch. (1994) La ética de la autenticidad, (Barcelona, Paidós). VELARDE, V (1986) La pretendida legitimación ética de la violencia política, en J.A. IBÁÑEZ-MARTÍN, T. GONZÁLEZ BALLESTEROS y R. GÓMEZ PÉREZ, Por una cultura pacificadora, (Madrid, Urbión). WOETHIGTON, A C., HIGGS, H Factors explaining the choice of a finance major: the role of students' characteristics, personality and perceptions of the profession, Accounting Education, 12, (1), 1-21. ZUBIRI, X. (1997) Cinco lecciones de filosofía, (Madrid, Alianza). 25 26