Kashmir

advertisement

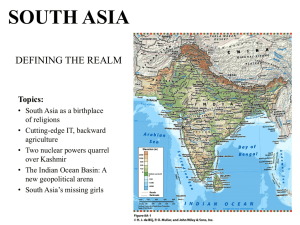

Suprita Kudesia IRP 601 – Fundamentals of Conflict Studies Final Paper December 16, 2006 Professor Bruce Dayton 1 L-28, Kalkaji, New Delhi 110048 December 15, 2006 Ms. B. Piece Senior Program Officer United States Institute of Peace 1200 17th Street NW – Washington, DC 20036 Dear Ms. Piece I am writing on behalf of Parivartan, a non-governmental organisation engaged in social entrepreneurship based in New Delhi since 2002. Parivartan believes in social and political change through the empowerment of the local people and is currently involved in supporting local business projects such as handiwork and textile printing in the western Indian state of Gujarat. We wish to be involved in the making of a more egalitarian Indian populace not ridden by poverty, hunger, disease, and injustice and are concerned about the state of Jammu and Kashmir with regard to the Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan. We are proposing a project that would, in the long-term, aim to politically empower the Kashmiris to fight for their right to self-determination through a democratic process. Recognising that this goal is extremely hard to achieve given the complexity and duration of the conflict, Parivartan hopes to at least transform the conflict to make it less intractable. Our proposal is a two-fold program that will seek to promote economic growth and the creation of a shared identity rooted in a common past. Parivartan is proposing to the USIP because of the organisation’s commitment to transforming international conflicts and helping re-build a stable post-conflict environment. We look forward to hearing from you. Thank you Sincerely Suprita Kudesia Senior Program Officer, Parivartan 2 Conflict analysis On August 14, 1947 Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru spoke about the destiny of India as a free country liberated from colonial rule on the edge of a new life. Inspired, he spoke that the “past is over and it is the future that beckons to us now” (Nehru 1947). He couldn’t have been more wrong in this regard. The effects of colonialism and India’s partition still remain in the form of one of the most cited intractable conflicts over Kashmir. India and Pakistan have fought four wars since 1947 – three over Kashmir and the fourth impacting the Kashmir issue nonetheless. To understand the complexities of the Kashmir conflict, an analysis of the historical origins of hostilities is undoubtedly required. Addressing the emotional, social, and political interests of the various stakeholders in the conflict is also necessary to grasp this long overdrawn India-Pakistan rivalry that extends itself to beyond territorial borders and affects arenas in the film, sport, and literature industries among others. Despite international recognition of Gandhi’s non-violent struggle, India’s (pre1947 political entity) path to freedom had been bloody, violent, and long. The separation of the country and the creation of an arbitrary border cutting across the middle of the state of Punjab on the basis of religion was an abandonment of the secular unity that had epitomised the freedom struggle. It was, however, another success of the British Raj. During British rule, India had been divided into British-controlled provinces and princely states. The princely states were technically independent as long as they accepted the supreme authority of the British crown and abdicated their control over defence, foreign affairs, and communications in the state (Ganguly, 1995, 169). As independence drew Raj is a Hindi word meaning rule and is commonly used to refer to the British rule in India. 3 near and the Muslim League’s call for a Muslim state entity, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, became a reality, the princely states were given the choice of joining either India or Pakistan. States sharing a border with Pakistan and/or with a predominantly Muslim majority would go to Pakistan. Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), crowning India and nestled in the Himalayas, proved to be problematic in this regard with a predominantly Muslim population, a shared border with the nascent Pakistan, and a Hindu maharaja keen on an independent political entity (Ganguly, 1995, 169). Further, even as a predominantly Muslim state is a narrow view of this much contested territory. J&K has three distinct regions incorporated into one state – Hindu dominated Jammu, Muslim dominated Kashmir, and a small Buddhist dominated Ladakh region in the high reaches of the snow-capped Himalayas (Varshney 1007). At the time of independence, the autocratic rule of the maharaja of J&K was being challenged by a secular movement led by Sheikh Abdullah who was ardently supported by Gandhi, Nehru and other political leaders. When the state refused to join either Pakistan or India, a rebellion supported by Pakistani troops invaded its territory in October 1947 and proceeded on a mass slaughter spree of the Hindus in the Jammu area. The maharaja sent an urgent request for troops from neighbouring states but was not able to quell the violence. The newly appointed Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru agreed to send troops if the maharaja would sign the Instrument of Accession to India (Ganguly, 1995, 170). This accession was created on a temporary basis with the Indian government promising to grant the Kashmiris a plebiscite once peace reigned. This of course has not happened to this day. There were two primary Indian political parties in British India – the Indian National Congress led by Jawaharlal Nehru who was to become the first prime minister of independent India and the Muslim League led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah who wanted to create a Muslim state for sub-continent Muslims. 4 The maharaja signed accession to India on 27th October 1947 and New Delhi sent troops to protect what was now Indian territory. The first and longest war fought between India and Pakistan ended with Pakistan having claimed a part of Kashmir. This area is referred to by Pakistan as Azad (Free) Kashmir and is referred to by India as Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (PoK). This region along with the greater Kashmir region in the state of Jammu and Kashmir is the disputed territory between India and Pakistan. The 1947-48 war between India and Pakistan ended with India seeking UN mediation on 1st January 1948. On 26th January 1948, India adopted her constitution that provides for, among other things, J&K under article 370 titled Temporary provisions with respect to the State of Jammu and Kashmir (“Part XXI…”). As is evident, the article is only an ephemeral arrangement for the problem of Kashmir but nonetheless denies it the power to hold elections. “Not withstanding anything in this Constitution, the provisions of article 328 shall not apply in relation to the State of Jammu and Kashmir;” article 328 being Power of Legislature of a State to make provision with respect to elections to such Legislature (“Part XXI…”). It can be persuasively argued that already Kashmir was going to be an integral part of the Indian political entity – one that the Indian government and people would not give up and therefore, any promise of a plebiscite was only a farce. The partition had been bloody with massive Hindu-Muslim violence and refugees pouring in and out of both countries. One has only to look at the literature written; films made; or listen to anecdotes. My grandmother lived in Lahore but had to flee with her family and few precious possessions to India after witnessing her uncle and cousins killed by her Muslim neighbours. War time chaos reigned with brutal rapes and murders; trains left each side of the new border with frightened families only to arrive at their destination 5 carrying mutilated and dead children, young and old women and men. The horrors of the Raj were yet to be fully experienced – another instance of colonialism leaving its long legacy. Stories of violence abound on both sides. Kashmir soon became the emblem of new identities created by the partition. Pakistan claimed Kashmir because of its predominantly Muslim population and shared border. India fought back because Kashmir became the symbol of secular India and also the added complexity of Kashmiri independence giving rise to secessionist movements in other parts of India (Ganguly, 1996, 79) especially the North East which has been plagued by identity conflicts too. While India and Pakistan strode forward as post-colonial players in the international arena, the Cold War was raging and affecting much of the world. The Indian sub-continent was no different. “In 1954-55 on grounds that Pakistan was on the periphery of the Soviet Union in the Middle East, the U.S. offered a security alliance to Pakistan” which it accepted (Varshney 1010). The Soviet Union was not to be left behind and quickly began supporting India in the UN and offering veto possibilities to the American agenda in the sub-continent. The plebiscite that had been promised to the Kashmiris nearly a decade ago was withdrawn by Nehru on grounds that Pakistan’s existence in Kashmir was illegal, Kashmir had accepted the Indian constitution, and the Cold War had changed the situation (1011). There has been no turning back since and the conflict has only gotten more entangled and intractable. The second Indo-Pak war was fought in 1965 – another Pakistani attempt to (re)claim Kashmiri territory. The Pakistani army initially attacked barren wasteland area in the western state of Gujarat and upon receiving only a lukewarm Indian response, confidently began planning more aggressive tactics. The Pakistani idea 6 was to stage a rebellion in J&K by infiltrating Pakistani troops and gaining territory by surprising the Indian government in the ensuing chaos. However, the Kashmiris did not support the rebellion and reported the infiltrators to the Indian government (Ganguly, 1995, 172). The war ended in a tactical, strategic, and humiliating Pakistani defeat and the Tashkent agreement with both sides promising to resume diplomatic and economic relations. The peace, however, was short-lived. The third Indo-Pak war was fought in 1971 over the issue of former East-Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. The political division of Pakistan as East Pakistan became the sovereign and independent Bangladesh was another humiliating defeat that affected Indo-Pak relations as recalcitrance over Kashmir grew and became a prime contest for national pride and prestige. 1971 saw the signing of the Simla Treaty which cemented the border between PoK and Indian Kashmir as an international border that would be respected by both sides as any other international territorial confine (Varshney 1013). This border has come to be known as the Line of Contol (LoC) which frequently experiences border skirmishes and cross-fires (Appendix A). In the midst of this growing Indo-Pak political animosity, there has also been a progressively intensifying discontent and disillusionment of the Kashmiri people against the Indian government. There has been an increasingly popular insurgency movement since December 1989 in Kashmir as various ideological groups claim the right to an independent state and oppose Indian rule in Kashmir (Ganguly, 1996, 76). These include the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF), Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, and Lashkar-eToiba (LET) among others. During the rise and high points of the insurgency in the 7 1990s, Islamic insurgency groups were actively supported by Pakistan. “Almost every shop in the main bazaar of every town, large or small, in Pakistan had a Lashkar collection box to raise funds for the struggle in Kashmir” (“Profile…” 2006). If I may jump ahead in my historical analysis for a brief moment, it would be pertinent to point out that the 11th July 2006 co-ordinated attacks on the Mumbai metro system were carried out by LET (“Asia…” 2006). Many of these insurgent groups aim not only for the freedom of Kashmir from Indian rule but also to extend Islamic rule to India. They also benefit immensely from the chaotic political situation in Kashmir because it provides them with a huge bulk of a vulnerable population with enough grievances to recruit to fight for their ideologies. The insurgency has only soured Indo-Pak relations further and in most cases delayed bilateral talks between the two countries. Further, since the September 11th attacks on the US and the global war on terror, Pakistan has been pressured to clamp down on these terrorist groups. President Musharraf has banned LET and three other terrorist groups although “after the ban [his] government did not try to break up Lashkar but it restricted the movements of its leaders and the group members were told to keep a low profile” (“Profile…”). Ganguly (1996) argues that there are two main reasons for the rise and steady presence of the insurgency in Kashmir which extends its violent nature into the rest of India. As the Indian government promoted development of its states through education, a new generation of young Kashmiris were made more cognizant of their rights and called for political mobilisation and the freedom of Kashmir (80). This was also accompanied by a “deinstitutionalisation of politics in the state, which drove the expression of political 8 discontent into extra-institutional contexts” – mainly insurgent groups (80). The insurgency has undoubtedly embittered Indo-Pak relations and led to an intensification of the security threat that both feel. The insecurity of the region was heightened in 1998 when India announced its nuclear capability with Pakistan following soon after. Both have also not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Since then both countries have increased their defence budgets despite a number of sanctions in light of the nuclear tests (Ganguly & Biringer, 908). With the Indian subcontinent now nuclear, the threat of the Kashmir conflict began to attract increasing international concern. Both India and Pakistan trudged along the path of uncompromised ideals. However, 1999 began with the Indian prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee taking an historic bus trip to Lahore on the invitation of then Pakistani premier Nawaz Sharif (Kapur, 195). There was much celebration as the Indian and Pakistani PMs exchanged garlands of flowers and the local people cheered. Hopes for a real peace building effort were rekindled. Countless Indians and Pakistanis forced to move at the time of partition dreamed of going back to their ancestral homes. Five decades after the conflict began, there seemed to be a real chance that the political process would move forward and there would a real attempt at a cessation of hostilities. However, deeply-rooted historical conflicts with identities, political interests, and national pride at stake are rarely forgotten with an unusual bus ride into enemy territory. While political niceties between the Indian and Pakistani leaderships were going on, Parvez Musharraf, then chief of the Pakistani army, was planning an incursion into Indian territory by Pakistani troops and Kashmiri militants in an effort that was reminiscent of the 1965 war. The LoC passes through extremely rugged territory among 9 the craggy slopes of the Himalayan range with impassable weather for most of the year. There had been a tacit agreement between India and Pakistan that certain areas of the LoC would be unmanned during the peak of winter with the expectation that neither side would take advantage of this vulnerability and respect the international border (“War…”). The hope was that the Indian army would not detect the infiltrators until May which they didn’t. This gave the Pakistani army and militants considerable time to occupy strategic positions along the LoC. The main Srinagar-Leh national highway was in clear range which gave them tactical advantage as it was the only route the army had to the higher reaches of the border between India and Pakistan. Had the incursion been successful, the LoC would have inevitably been redefined because India would not have been able to fight back with its only highway connecting them to the infiltrators being manned by the infiltrators themselves. The Indian offensive was launched on 26th May 1999 and called Operation Vijay (victory). Patriotism was flying high as India was deeply offended by the under-handed infiltration with a clear goal of redefining the international border and claiming Indian territory. The war ended with India successfully pushing back the infiltrators across the original LoC and Pakistan condemned by the international community for what was a clear act of unprovoked aggression and infiltration into Indian territory. Soon after, Musharraf led a military coup against Prime Minister Sharif and declared himself President. With mistrust high between the two countries and the demise of democracy in Pakistan, any diplomatic progress that had been made toward peace was stalled. September 11th brought the Indo-Pak conflict over Kashmir back into the limelight as the US pressured Pakistan into banning terrorist organisations and providing 10 refuge for the Taliban. The Indian and Pakistani people share a common history and a hard struggle against colonialism. Yet they were separated along religion which can be a deeply contentious identity issue. I would argue that the Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan is deeply rooted in identity and emotion. The pride of the Indian and Pakistani people relies on the future of Kashmir. The insurgency has shown that what the Kashmiris themselves want is independence and autonomy. Thus, you have the three main stakeholders in the conflict at cross-purposes, each fighting for a non-negotiable national identity. It is no wonder that this is a classically defined intractable conflict. But to define the stakeholders as simply the Pakistanis, the Indians, and the Kashmiris would naturally be too simplistic and belie the complexity of the conflict. The promised plebiscite to the Kashmiris is long overdue; there isn’t even a permanent provision for the state in the Indian constitution as mentioned earlier. However, the state of Jammu and Kashmir consists of three distinct territories with three diverse religious populations. The Kashmir conflict makes them all important stakeholders especially as most of the people living there have lived their lives under constant threat of violence. The future of Kashmir will determine not only the future of the Kashmiris, but also the people of Ladakh, Jammu, and other parts of J&K. An important question that needs to be asked is what an independent Kashmir would mean for the rest of the state. The Kashmir conflict has also inflamed religious animosity between Hindus and Muslims in India which threatens the secularity that the country proudly claims. The 1992 Mumbai and 2002 Gujarat Hindu-Muslim riots horrified not only the international community but also the Indian population. India was reminded of the deep cleavages in its population. The Hindu nationalist party (BJP) in government at the time was 11 undoubtedly threatening to a significant size of the population. Though the majority of Indians are Hindus, on account of sheer size of the population, India has a fair number of Muslims, Christians, and Buddhists among other religions. The Kashmir conflict threatens the delicate balance that the diversely secular Indian population lives in. Military insurgency groups such as the LET are increasingly attempting to ruin this balance in hopes for a resolution to Kashmir. The 2005 bombings in a public market in New Delhi during the festive celebrations of the Hindu festival of Diwali and the Muslim festival of Eid-ul-Fitr and the 2006 Mumbai metro bombings by the LET were strategically implemented to fracture religious communities and tolerance in India and weaken the Indian government. Finally, in light of the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers in a highly globalised and interconnected world, more so since the global war on terror that deeply affects Indo-Pak relations, the larger international community also has a stake in the Kashmir conflict. Although not a major theatre in which the war on terror is being played out, the Kashmir conflict has seen the involvement of Afghan mujahideen and Al Qaeda. The transformation of the Kashmir dispute would affect the war on terror that the international community is implicated in. Thus, due to the deep historical roots of the conflict tied in national identity and an ethos of emotions associated with pride and justified claims to common territory, and the implication of a diverse group of stakeholders, it is incumbent upon the Indians, Pakistanis, Kashmiris, and the international community to work toward the metamorphosis of the conflict. So far I have attempted to highlight and provide contextual explanation of the development and perpetuation of the Kashmir conflict between India and Pakistan. I have 12 introduced the three main groups of stakeholders in the conflict – the Indians, the Pakistanis, and the Kashmiris. My discussion and chronological overview of the IndoPakistan conflict over the territory and people of Kashmir has attempted to underscore the complexity in analysing the conflict through multifarious lenses and stakeholder groups. This intricacy of the Kashmir conflict is not an unusual feature. Randall (“Fundamentals…” 2006, 324) writes that “conflict is not merely just one more factor among others, it is an expression of the very multidimensionality of things, the plurality of different groups, interests, and perspectives that make up with world.” The conflict over Kashmir epitomises this sentiment. Despite the existence of a common past, the stakeholders have moved further away from their shared stories and experiences. Diplomatic efforts at “resolving” the conflict have thus far only attempted to address the superficial territorial claims to Kashmir. However, to change the status quo a conflict transformation strategy has to address the causes and features of the rift between the stakeholder groups. One of the key issues that have to be dealt with before a transformation strategy is proposed is to confront the role that identity plays in the Kashmir conflict. Northrup defines identity as “an abiding sense of selfhood…” or a “core construct” in the sense of self (“Fundamentals…” 173-4). This is central to understanding the Kashmir conflict because no individual or group will be willing to negotiate their concept of their self. Diplomatic and political mediation to the conflict has been based on a negotiation or compromise policy. While it is accepted that the three main groups of stakeholders have different interests that they want realised in a transformation strategy, these interests can at least be negotiated. However, none of the stakeholders will ever compromise on a 13 point if they believe it is central to the way in which they think of their existence or their self-concept of who they are. The common belief that India will not be India without Kashmir is referring to exactly this concept. Somehow, Kashmir has become a key part of the Indian identity which in and of itself is an extremely vague and possibly non-existent idea. However, when social policy, film, art, and sport are framed in this manner, the people begin to assume this identity. The same can be argued for Pakistan. Any individual or group has multiple identities that might only exist in the subconscious. But Northrup argues that a threat to an identity brings it to the forefront and elicits all possible measures to maintain the existence and perpetuation of the identity (“Fundamentals…” 174). Losing Kashmir poses to both India and Pakistan the prospect of losing a core sense of their ‘Indian-ness’ or ‘Pakistani-ness.’ Continuing to being subservient to the political whims of either government presents the Kashmiris with the threatening prospect of losing their Kashmiryat. These concepts of self are clearly not negotiable and stall any attempt at transforming the conflict even before a strategy is implemented. In the case of Kashmir, the three main conflicting identities were created during the British rule. Although superficial in its origin, this legacy of the Raj continues to dominate sub-continent politics, has been the cause of four wars, human rights violations, and a prolonged insurgency. To overcome the intractability of the conflict, super-ordinate identities that bring the stakeholders with diverging identities and seemingly distinct interests together in a non-threatening manner need to be established. The insurgency, which has its roots in state interests and identity politics, has also fragmented the social and economic fabric within Kashmir. The six-decade long conflict 14 has resulted in structural violence that is not commonly acknowledged by either the Indian or the Pakistani government. Kriesberg writes that the structural factors shaping a conflict “influence self-conceptions and identities, how grievances are experienced and interpreted, what goals are formulated, and the methods used to obtain them” (“Fundamentals…” 109). Thus, structural factors interact with and impact cognitive (how the conflict is framed), interest (of various parties), and emotive aspects of the conflict. The already mentioned temporary nature of the provisions for the state of Jammu and Kashmir in the Indian constitution points to the vulnerability of the state to Indian political whims. The hypocrisy in Indian politics shines through as it claims J&K as the crown of the Indian territory but simultaneously does not grant it equal political status as other states. This systemic prosecution of the Kashmiri people by the Indian government has resulted in the disillusionment of the Kashmiri people. An unhappy and angry population has proved an easy target to the Pakistani funded and ideologically supported insurgency. Already a transformation strategy seems unbelievably complicated and impossible. Not only would a super-ordinate identity that encompasses the Indians, Pakistanis, and the Kashmiris in some way have to be created; but also the structure of life as the Kashmiris know it would have to be re-organised so as to stop the systemic violence that has resulted from it. Project goals Contemporary Indo-Pakistan relations have a common history of struggle against foreign rule, a bloody partition, and national interests rooted in threatened identities and emotions. Despite this the governments cannot seem to arrive at a satisfying way to re- 15 frame the conflict to reflect these shared grounds of their relationship. Thus far the people of Kashmir have been made casualties of political agendas of Indian and Pakistani government policies. As mentioned before, the constitutional power granted to Kashmir by India is only superficial and designed to perpetuate the status quo of the conflict. Parivartan believes that the Kashmir conflict cannot be transformed through traditional diplomatic processes which have in fact, as is evident from the above historical analysis, served only to perpetuate the conflict rather than resolve it. The long term goal of Parivartan is to act as a platform for empowerment of the Kashmiris so that they can have a voice in the political process and can fight for their right to selfdetermination. However, with unemployment and violence rampant, the population needs to be provided with economic growth opportunities before it can participate in its own political processes. This is particularly true for the region that was affected by the October 2005 earthquake. As mentioned before, the Indian policy of deinstitutionalising politics, poverty, and unemployment in Kashmir has led to a disgruntled youth population that serves as ready fodder for the insurgency. The project that Parivartan is proposing hopes to metamorphose the current situation in Kashmir by creating an atmosphere not conducive to adolescents being recruited by the insurgency. The project will be implemented in the Azad Kashmir area which was the epicentre of the earthquake. Realising that this involves crossing the accepted international border, the LoC, Parivartan has already acquired structural support for the proposed project from its Pakistani counterpart Tabdeelee. 16 Project methodology and expected results The project will be implemented in the Azad Kashmir area which was the epicentre of the earthquake. Parivartan will set up a vocational school in the town of Kathai which will enroll all individuals between the ages of 13 -19 years and orphaned children of all ages. The vocational school will offer activities and classes on acquiring competence in carpentry, tailoring, plumbing, electrical, and telecommunication technical skills. Possession of these skills will make graduates of Parivartan’s vocational school marketable in the economy of the region. Alongside the vocational skills, Parivartan will also offer lessons on learning to read and write in English, Hindi, and Urdu so that the youth from the insurgency-ravaged and earthquake-hit region can travel to other parts of the Kashmir state and look for jobs. We have already obtained the services of teachers who were working in local schools in the region but were destroyed after the earthquake. They have expressed willingness and enthusiasm to be involved in the project and to be given the opportunity to work again. To expand the impact of this educational program, Parivartan will also run a bus service to surrounding villages and towns and bring children to the vocational school so that they are given the opportunity to build expertise at particular skills and are able to participate in their own and their state’s economic growth. Due to the poor infrastructure of roads in the region, Parivartan will offer a morning pick-up and evening drop-off ride within a 20 kilometre radius. On weekends, Parivartan will offer in-residence vocational skills sessions to individuals living in a 50 kilometre radius where participants will have the opportunity to stay on the organisation’s premises. 17 As mentioned in the historical analysis of the Kashmir conflict, ideas of conflicting identities is also at the root of the conflict. To accomplish the long-term goal of political empowerment of the Kashmiris and the transformation of the conflict to allow for a cessation of the insurgency movement and possible independence for the Kashmiri people, economic growth will not suffice on its own. Economic empowerment has to be accompanied with a program for increased contact between the PoK residents and Indian Kashmiris in order for their Kashmiri identities to supersede superficial national identities that have been imposed on them. Parivartan, and its Pakistani counterpart Tabdeelee, will work together on a facilitated contact program by allowing for opportunities for people from either side of the border to meet and interact with each other. To this end, both Parivartan and Tabdeelee have already planned “cultural exchange programs” which will occur once a month. In these programs, three families from PoK and Indian Kashmir will be chosen on a volunteer and lottery basis and participate in the exchange program which will involve them visiting their host family and their host family visiting them for one weekend every other month. The host families will organise activities to engage their guests which will be supervised by Parivartan with the hope that sustained contact between the families will re-establish their common histories and enable the enactment of a common superordinate identity over their artificial Indian or Pakistani identities. The initial time frame for Parivartan’s project is one year. The vocational skills trainings will occur in three month sessions allowing for four sessions to take place within one year. The “cultural exchange programs” for facilitated contact will occur once a month for twelve months – six months in Indian Kashmir with Indian Kashmiris as 18 hosts and six months in PoK with Pakistani Kashmiris as hosts. Meticulous examination of the success or failure of these programs will occur at the end of the one year period. The results of the evaluation will determine whether and in what manner the programs need to be modified to better achieve Parivartan’s short-term goal of economic empowerment of the Kashmiris and facilitated contact to establish a super-ordinate Kashmiri identity, and long-term goal of political empowerment of the Kashmiris to be able to fight for their right to self-determination. Evaluation design The design of the vocational skills program allows for a follow-up period for the first three groups. In other words, the progress of the group of children and adolescents who graduate from the first session will be evaluated until the end of the project which will give Parivartan nine months of follow-up time. The second group will get six months and the third group three months of follow-up time. During this time, Parivartan will remain in close contact with the participants of the vocational skills program and maintain a record of how many individuals got jobs, kept their jobs or changed them, and the change (if any) in their and their family’s economic condition. At the end of the year, Parivartan will compile this data and look for patterns of change that can be attributed to the vocational skills program directly. Such patterns of change would include participants acquiring and keeping jobs in the area of their vocational training thus impacting in a positive manner their economic status. Such data can be objectively compiled and analysed and will serve to demonstrate any applicability and advantages of the Parivartan program there might be in helping to transform the status quo intractability of the Kashmir conflict and its impact on the local people. 19 Evaluating Parivartan’s “cultural exchange” program for facilitated contact will be a much more complicated task because there is no quantitative and objective method to measure a change in attitude and the re-framing of identities. The performance indicators of this goal will be much more nebulous keeping in mind the fact that a conflict entrenched in diverging identities that has carried on for six decades is not likely to change within a year of facilitated contact. More importantly, Parivartan’s short-term success or failure with regards to the “cultural exchange” program can be assessed through a pre- and post-exchange program survey of attitudes. This survey will point toward the initial effectiveness or incompetence of the program which will allow Parivartan to make appropriate changes to ensure its long-term goal of re-framing identities. This will occur, as mentioned before, on the assumption that sustained interaction will humanise the “other” by creating common interests, common stories, and re-establishing a common history that will come through in sustained interviews with the participants. These interviews will be meticulously coded following tested and reliable qualitative coding methods to measure the medium-term success of Parivartan’s “cultural exchange” facilitated contact program. Conclusion I have attempted to highlight the need for a non-government initiative in Kashmir to change the status quo situation and at least begin to transform the conflict. I have established in my conflict analysis that the Indian and Pakistani premiers have only perpetuated the conflict by not giving the Kashmiris the right to due process and by encouraging and financially supporting the insurgency respectively. Meanwhile, the Kashmiri people continue to suffer in what can very easily be labelled a humanitarian 20 crisis situation. It seems only appropriate to turn to NGO and Track II diplomacy initiatives, some of which are being proposed for by Parivartan. The vocational skills and “cultural exchange” facilitated contact projects are aimed at transforming the conflict in a two-pronged approach. By aiming to ameliorate the economic condition of the Kashmiris, Parivartan believes that political empowerment will be possible through which the Kashmiris will be equipped to fight for their right to self-determination. By aiming to organise facilitated interaction between the Indian and Pakistani Kashmiris, Parivartan hopes that super-ordinate identities of common Kashmiriyat * will emerge over current national and religious identities. Collectively, the two goals and projects aim to transform the Kashmir conflict in a feasible and peaceful manner. * Hindi/Urdu word for “Kashmiriness” 21 Appendix A Figure 1. A map of Kashmir showing the LoC and PoK† † http://worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/asia/kashmir.htm 22 References “Asia: Bomb-blast diplomacy; India and Pakistan.” Economist 7 October 2006: 76. Dayton, B., ed. Fundamentals of Conflict Studies Course Reader. Syracuse: The Copy Centers, 2006. Ganguly, S. “Wars without End: The Indo-Pakistani Conflict.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 541 (1995): 167-198. Ganguly, S. “Explaining the Kashmir Insurgency: Political Mobilisation and Institutional Decay.” International Security 21.2 (1996): 76-107. Ganguly, S. and Biringer, K.L. “Nuclear Crisis Stability in South Asia.” Asian Survey 40.1 (2001): 907-924. Kapur, D. “India in 1999.” Asian Survey 40.1 (2000): 195-207. Nehru, J. “Tryst with Destiny.” On the granting of independence to the Indian people. 14 August 1947. “Part XXI: Temporary, Transitional, and Special Provisions.” The Constitution of India. 30 Oct. 2006. http://www.constitution.org/cons/india/const.html “Profile: Lashkar-e-Toiba.” BBC. 17 Mar. 2006. 30 Oct. 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/3181925.stm “Timeline: Ayodhya Crisis.” BBC. 5 July 2005. 30 Oct 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/4536199.stm Varshney, A. “India, Pakistan, and Kashmir: Antinomies of Nationalism.” Asian Survey 31.11 (1991): 997-1019. “War in Kargil.” Center for Contemporary Conflict. 30 Oct. 2006. http://www.ccc.nps.navy.mil/research/kargil/war_in_kargil.pdf 23