Here - Bloomsburg Theatre Ensemble

advertisement

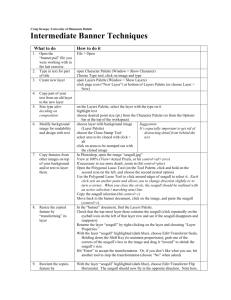

Table of Contents -Setting -Synopsis -Characters SEAGULL -Love/Lust map - Chekhov -Rough Voyage -Director’s Note -Adapting the Play -Music used in our adaptation -Questions -Works cited By Anton Chekhov Adapted by Laurie McCants If you’ve ever texted a friend about… how the cute boy/girl in your English class loves someone else how your parents don’t give you what you want how NO one “gets” you Then SEAGULL is the perfect play for you! The Seagull- A comedy in four acts. By Anton Chekhov, 1896 SEAGULL- A comedy, kind of, in two acts. Adapted by Laurie McCants, 2014 Anton Chekhov, playwright (1898, by Osip Braz) The Seagull (Chayka ) This slice-of-life drama, originally set in the Russian countryside at the end of the 19th century, was first performed in St. Petersburg on Oct. 17, 1896. BTE’S production SEAGULL, adapted by Director, Laurie McCants, is set at a summer house at a lakeside resort in the Endless Mountains, in northeastern Pennsylvania. Time: Summer, 1965; then late autumn, two years later. 1 Eagles Mere Playhouse Publisher: Joe Kast …so much love! — Eugene, SEAGULL SEAGULL SYNOPSIS A synopsis for this adaptation of SEAGULL (bear in mind as you read this that Chekhov called his play a “comedy”—a synopsis such as this cannot capture all that’s funny in the play, which has a lot to do with what’s funny in life, but it can reveal the play’s underlying tragedy, which also has a lot to do with life): 1965. It’s a beautiful summer evening on a lake in the Pennsylvania mountains, and family and friends are gathering to watch the first performance of Constantine’s avant-garde play. Love in all its astonishing and confounding variety is revealed as the evening unfolds. Simon loves Marsha, who secretly loves Constantine, who’s in love with Nina; Nina has a celebrity crush on Boris, the famous writer she’s about to meet; Pauline, married to John, still wants to keep the dying embers of a decades-long affair with Eugene glowing. The performance is not a success. Constantine stops it and stomps off. He had wanted his play to impress his famous-actress-mother, Irina, and captivate Nina, its star. But Nina is drawn to Irina’s lover, Boris, who embodies the artistic fame that she craves. A few days later, Constantine, who has tried to shoot himself (he missed), appears before Nina and places a dead seagull at her feet. He has shot it, he tells her, as he will one day shoot himself. She is confused and repulsed, but Boris, ever the writer, is intrigued. The dead bird sparks his idea for a story about a girl, “happy and free,” who is destroyed by a man, “just like this seagull here.” Irina’s aging brother Peter is fond of his nephew Constantine, and hoping to help the young man out of his woes, Peter asks his sister to give Constantine money to travel and spread his wings. Tight-fisted Irina says no. There is a brief reconciliation between mother and son as she helps him change the dressings of his selfinflicted wound, but their conflicts re-surface quickly and Constantine stomps off again. Irina is soon confronted by another request for freedom; Boris begs her to release him so he can pursue Nina. Irina’s passionate refusal temporarily quells him, but when he learns that Nina is running away to become an actress 2 in New York City, Boris arranges to meet her there. 1967. Two years later. It’s a bleak late fall evening at the lake. Marsha has married Simon, but like her mother, she’s still in hopeless love with another. Irina and Boris (who has returned to her after his fling with Nina) are visiting the cottage, as is Eugene. Constantine fills Eugene in on what has happened to Nina. Her affair with Boris fizzled, she had a baby who died, she’s pursuing her acting career by taking jobs at third-rate theatres. Constantine, too, seems stuck. While he’s had several of his stories published, he fears he’s fallen into the same artistic complacency he once despised. While the others have gone into another room for dinner, Constantine reads over a draft of one of his stories with increasing despair. Nina suddenly appears. At first she seems distraught, calling herself “the Seagull.” Constantine tells her he feels dead without her. But she’s been hired by a provincial theatre company and cannot stay. And though she admits that she’s still in love with Boris, she also knows that she has found the strength to survive. Then she goes. Left alone, Constantine slowly rips up his manuscripts and leaves. Nina, Boris and the others return and resume their card game. And in the next room, a shot is heard. Constantine has killed himself. CHARACTERS: IRINA/Irina Nikolayevna Arkadina BORIS TRIGORIN/Boris Alexeyevich Trigorin (A famous author) (Star of stage and screen) James Goode Elizabeth Dowd CONSTANTINE/Konstantin Gavrilovich Treplyov (Irina’s son, a young man) Eric Wunsch PETER SORIN/Pjotr Nikolayevich Sorin (Irina’s brother, elderly, owner of their lakeside cottage, a retired lawyer) Andrew Hubatsek NINA/Nina Mikhailovna Zarechnaya EUGENE DORN/YevgenySergeyvich Dorn (a young neighbor girl) (A local doctor) McCambridge Dowd-Whipple Daniel Roth MARSHA/Masha SIMON/Semyon Semyonovich Medvedenko (John and Pauline’s daughter, a young woman) (A young man, a local school teacher) Cassandra Pisieczko Richard Cannaday 3 PAULINE/Polina Andryevna JOHN/Illya Afanasyevich Shamrayev (Manager of Sorin’s property) (John’s wife) Robert Cividanes Samantha Norton JAKE/ Yakov (A hired hand) Rhys Kauffman “If ever my life can be of any use to you, come and claim it.” (The tangled web of love and lust in SEAGULL) Irina is in love with herself Irina and Boris are in a “celebrity” relationship. How long will it last? Nina Seduces Boris with flattery-Boris craves a mid-life affair with a younger woman Constantine is jealous of his mother’s attention toward Boris Constantine is madly in love with Nina. Nina has her eyes on a bigger prize! Marsha is madly in love with Constantine- Constantine can’t run away fast enough Simon is madly in love with MarshaMarsha keeps him waiting in the wings 4 Pauline jealously pines after Eugene Eugene, once the “ladie’s man”, is indifferent Pauline is the frustrated wife of John- Does John know about Pauline’s passions for Eugene? Anton Chekhov b.Jan.29, 1860 d. July 15, 1904 Anton Chekhov lived in Taganrog, Russia. Chekhov was a trained medical doctor in Moscow. He was a playwright, novelist, and short story writer. He mainly focused on writing fiction. His best plays and short stories lacked complex plots and neat solutions. His family had trouble financially therefore he had to pay for his own tuition. His most famous works were The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters, The Cherry Orchard, The Black Monk, Neighbors, and Lady with the Dog. He is regarded as the outstanding representative of the late 19th-century Russian realist school. THE ROUGH VOYAGE From October to November, 1895, Chekhov wrote The Seagull, the play that deliberately flouts the stage conventions of nineteenth-century theatre; the genre where Irina is famous. Nineteenth Century Theatre embraced - A starring role - Dramatic action building with each act - There is always dramatic crisis - Characters are bigger than life Chekhov’s The Seagull - There is no “star” - Dramatic action declines with each act - Intentional avoidance of dramatic crisis - Characters are everyday people As his first effort in a radically new form of dramatic playwriting where he uses a tone of ambivalence and a resistance to labelling his characters as villains and heroes, The Seagull shows Chekhov’s creative 5 originality. However, some believe the play is flawed by the heavy-handed symbolism, using the dead seagull to represent hopes betrayed. On October 17, 1896, at the Alexandrine Theatre in St. Petersburg, The Seagull premiered and was a flop due to the cast being under-rehearsed, and the requirement that a well-known comic actress be cast. ... The audience’s angry response to the play was both immediate and intense. They were hissing the performance by the end of the first act. They loudly criticised the play for its lack of action and recognisable characters. The actress playing Nina, Vera Kommissarzhevsky, whose work Chekhov had praised highly in rehearsals, was so terrified by the audience’s response that she lost her voice. The audience, it has been argued, were used to seeing light vaudeville shows at the theatre, so their dislike of Chekhov’s naturalistic and thoughtful play can be attributed to it the fact that it did not meet their expectations. Anton Chekhov reading his play, The Seagull, to the company of the Moscow Art Theatre Chekhov wrote to his brother the following day: ‘The play has fallen flat, and come down with a crash. There was an oppressive strained feeling of disgrace and bewilderment in the theatre. The actors played abominably stupidly. The moral of it is, one ought not to write plays.’ The same day he wrote to his publisher, Suvorin, ordering him to stop the publication his plays. He firmly insists that ‘I shall never either write plays or have them acted.’ He immediately left St. Petersburg and headed to his estate in the countryside outside Moscow. The experience had deeply knocked his confidence in his work: ‘I saw from the front only the two first acts of my play. Afterwards I sat behind the scenes and felt the whole time that The Seagull was a failure. After the performance that night and next day, I was assured that I had hatched out nothing but idiots, that my play was clumsy from the stage point of view, that it was not clever, that it was unintelligible, even senseless, and so on and so on. You can imagine my position—it was a collapse such as I had never dreamed of! I felt ashamed and vexed, and I went away from Petersburg full of doubts of all sorts. I thought that if I had written and put on the stage a play so obviously brimming over with monstrous defects, I had lost all instinct and that, therefore, my machinery must have gone wrong for good.’ Despite this failure, The Seagull returned to the stage in 1898—this time under the direction of Konstantin Stanislavski, founder of the Moscow Art Theatre. Stanislavski’s production was successful. So successful, that The Seagull graphic remains the logo for the Moscow Art Theatre to this day. Nina and Boris (Konstantin Stanislavski) http://www.niu.edu/theatre/_images/mxat_logo.gif Meyerhold preparing for his role (Constantine) 6 Director’s Note by Laurie McCants During the flood of 2011, confined to my house by the rising waters, I pulled down all my various translations of SEAGULL so that I could spend my time in a useful manner. I have something of a tormented history with this play, given that our mentor Alvina Krause directed it in the early years of BTE, and that was a troubled time for me. I wanted to rediscover it. To my surprise, I discovered that, yes! I absolutely love this play. It is so prickly, so beautiful, so funny, so sad. I laughed. I cried. I fell in love (again) with Chekhov. The Seagull was written in 1896 and it’s set in a lakeside resort in rural Russia. Partly because I wanted to make this play more easily accessible to our audience, and partly because of a kind of delight I take in BTE’s predilection for creating “plays about place,” and partly because I’m a kid of the 60s, I’ve set my adaptation in a lakeside resort in the Endless Mountains of rural Pennsylvania, 1965-1967. Miss Krause’s legendary Eagles Mere Playhouse had its final season there in 1965. For 20 years, she brought a busload of Northwestern University students there, a fresh bunch every summer. They lived in a lodge and at the Playhouse, they performed Alvina Krause, circa 1960 9 plays in 10 weeks, great heavens above. I amused myself by imagining those exhausted young artists, sitting around the campfire in the late summer evening, singing folk songs and downing contraband beers to drown out Miss Krause’s stinging criticisms still ringing in their ears following a fraught rehearsal (of SEAGULL?). In my adaptation, these became the singers Irina hears in a quiet-after-the-storm moment in the darkening lakeside twilight (Irina: “Listen! They’re singing! How lovely!” Pauline: “It’s those kids on the other side of the lake.”) My primary reason for returning to SEAGULL is that it’s time. It’s time to do Chekhov now. This play draws deeply on the strengths of our ensemble. The resonating web of interconnected lives, the tug and tussle between aging artists and younger ones struggling to be heard, to be recognized! Do we know something about this? Oh, yes, I believe we do. Challenges abound. It’s not an easy play to categorize. Is it a comedy? A tragedy? What the heck is it??? As resistant as it is to simple pigeon-holing, this much is certain: SEAGULL changed the course of theatre. It is now considered a masterpiece of the modern stage. Chekhov blew the dust off of 19 th-century overwrought melodrama and ushered in a new age of ambiguity, something resembling real life. As the playwright himself said, “I sin frightfully against the conventions of the stage.” And here’s another reason to set my adaptation in the 1960s. Just as Chekhov was at the forefront of a revolt against the theatre of his time, so Constantine in my SEAGULL hopes to be the playwright on the front lines (the avant-garde!) of the cultural revolutions of his time. There are no heroes or villains in SEAGULL. Just a bunch of folks making a ridiculous mess of their lives. As they did in 1896. And 1965. And continue to do in 2014. I’m very happy that we have chosen to bookend our 37th season with SEAGULL and VANYA AND SONIA AND MASHA AND SPIKE. With these two plays and the staged reading of American playwright Aaron Posner’s brilliant new work, STUPID F***ING BIRD (a stunning, funny/sad riff on SEAGULL), I can imagine the spirit of Chekhov floating above us, perhaps as a seagull sporting a goatee and a pair of pince-nez glasses. I hope he likes what he sees. Chekhov said that his play was full of “tons of love.” Tons of love to you, our audience. Thanks for being here. 7 The Challenges of Translation and Adaptation by Laurie McCants (director/adapter) About the translations of his plays into languages other than Russian, Chekhov had this to say: “I can’t stop them, can I? So let them translate away; no sense of it will come in any case.” About his “version” of The Seagull (performed in Central Park in 2001, with an all-star cast of Meryl Streep, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Christopher Walken, Natalie Portman, John Goodman, and Kevin Kline), the acclaimed British playwright Tom Stoppard said: “There are at least a dozen English translations of The Seagull in print and no doubt a dozen more still available. The polite convention in my present position is to apologize for adding another, and—modestly— to offer particular justification for it. But this is not necessary. You can’t have too many English Seagulls: at the intersection of all of them, the Russian one will be forever elusive.” I don’t speak or read Russian. For my adaptation, I have consulted a variety of English translations, ranging from very old to very new. I have also consulted with some Russian friends, avid Chekhov fans themselves, and after giving me some helpful tweaks, they approve of my SEAGULL. I have tried to remain true as I can to the sense of Chekhov’s play. Transferring the action to rural Pennsylvania in the 1960s has presented some fascinating challenges. For example, here’s a scene that happens in the second half of our first act. Irina wants to go into town. John says she can’t because the horses are all being used for necessary farm work. Here’s how that scene is translated in the English version available online through the Gutenberg Project (probably a very early translation; the translator is uncredited). I have left the character names as they are in this early translation; the character names from my adaptation are noted: SHAMRAEFF (“John”). Here they are. How do you do? [He kisses ARKADINA'S hand and then NINA'S] I am delighted to see you looking so well. [To ARKADINA] My wife tells me that you mean to go to town with her to-day. Is that so? ARKADINA (“Irina”). Yes, that is what I had planned to do. SHAMRAEFF. Hm—that is splendid, but how do you intend to get there, madam? We are hauling rye to-day, and all the men are busy. What horses would you take? ARKADINA. What horses? How do I know what horses we shall have? SORIN (“Peter”). Why, we have the carriage horses. SHAMRAEFF. The carriage horses! And where am I to find the harness for them? This is astonishing! My dear madam, I have the greatest respect for your talents, and would gladly sacrifice ten years of my life for you, but I cannot let you have any horses today. ARKADINA. But if I must go to town? What an extraordinary state of affairs! SHAMRAEFF. You do not know, madam, what it is to run a farm. ARKADINA. [In a burst of anger] That is an old story! Under these circumstances I shall go back to Moscow this very day. Order a carriage for me from the village, or I shall go to the station on foot. SHAMRAEFF. [losing his temper] Under these circumstances I resign my position. You must find yourself another manager. [He goes out.] Here’s the same scene from a very recent British production (2013), in a version by John Donnelly which endeavors to replicate Chekhov’s saltier language (often softened by early translators): 8 ILYA (“John”): The gang’s all here! Fantastic, good morning, wonderful health. My wife tells me you’re off to town together? IRINA: That’s right. ILYA: Wonderful, later today? IRINA: Yes. ILYA: No, why not? How you getting there? IRINA: How am I—the carriage? I— ILYA: And which horses are you…? IRINA: Whichever horses you normally… ILYA: Well, there’s the horses we’re using to move the rye. Are those the horses— IRINA: What’s he talking to me about horses for? I don’t know about horses! ILYA: Fine, I’ll shut down the estate for the day so you can get into town. PETR (“Peter”): What do you mean shut down, who said anything about shut down! ILYA: Who’s going to pull the carriage, muggins? PETR: The carriage horses. ILYA: Oh, the carriage horses. PETR: Yes. IRINA: I don’t-ILYA: And what about harnesses? PETR: What about harnesses? ILYA: There aren’t any. PETR: There aren’t any harnesses? ILYA: We have no harnesses! Of harnesses, we have none! IRINA: Look, I don’t give two hoots how, I just have to be in town. ILYA: Madam, when it comes to theatre, I bow down before you, I— IRINA: What’s this— ILYA: --worship at your feet, you can have ten years of my life, blood, sweat, and tears— IRINA: What’s this got to do with anything? ILYA: --but when it comes to farming, and I mean this with the greatest respect, you haven’t the first f*****g clue what you’re on about! IRINA: I am going to Moscow and I am not coming back. PETR: Oh God. 9 IRINA: I will not stay in this place another second with this man, get me some horses from the village or I will put the bit between my own teeth and pull the f*****g carriage myself! ILYA: That’s it! I quit! Find yourself another bloody slave. And here’s my adaptation, in which the language and situation have been updated to rural Pennsylvania in the 1960s: JOHN: And here they are! Good morning! (Makes a mock bow to all.) Wonderful to see all of you looking so well! My wife tells me you’re planning on driving into town today. Is that so? IRINA: Yes, we’re thinking we might. JOHN: Well, that’s just marvelous, but how will you manage that, dear lady? The tire needs to be changed on the T-Bird and we’re hauling rye today, so Jake and I are occupied, to say the least. We don’t have time to change a tire today. What vehicle were you proposing to take, may I ask? IRINA: What vehicle? How should I know what vehicle? PETER: We have the Caddy. JOHN: As you’ll recall, your esteemed sister drove it the other day and forgot to check the gas gauge. Where am I going to get gas today? I just don’t have time for this! This is incredible. Forgive me, dear lady, you’re a great actress, I worship you, I’d gladly give you ten years of my life, but I can’t give you a car today! IRINA: But what if I have to go into town today? This is really the limit! JOHN: Most esteemed lady, you have no idea what it means to run a farm! IRINA: The same old story! If that’s the case, I’m going back to New York today! Send someone to pick me up or I’ll walk to the station! JOHN: If that’s the case, I quit. I quit! I resign my position! Find yourself another manager! (He stomps off.) Why HOWL? In Chekhov’s play, Constantine expresses his disdain for the old-fashioned plays that his mother stars in, saying (as somewhat egregiously translated in that early edition reproduced online in the Gutenberg Project): “To me the theatre is merely the vehicle of convention and prejudice. When the curtain rises on that little three-walled room, when those mighty geniuses, those high-priests of art, show us people in the act of eating, drinking, loving, walking, and wearing their coats, and attempt to extract a moral from their insipid talk; when playwrights give us under a thousand different guises the same, same, same old stuff, then I must needs run from it screaming, as Maupassant ran from the Eiffel Tower that was about to crush him by its vulgarity.” Guy de Maupassant Well, now, what does a 21st century American audience make of this? What do we know about Maupassant and his reaction to the Eiffel Tower? Not much, is my guess. I had to look it up on Wikipedia. This is what the famous French writer, considered a “father of the modern short story,” had to say about the then-new tourist attraction in his home city: “I left Paris and even France because in the end, the Eiffel Tower annoyed me too much. Not only could you see it from wherever you went in the city, but you also found it everywhere, made in every material known to man, on sale in all the shop windows, an unavoidable and agonizing nightmare. It wasn’t only the Eiffel Tower, however, that gave me an irresistible desire to live alone for a while, but everything that was done around, inside, above and adjacent to it. Really – how could all the newspapers speak to us of a new architecture in relation to this metallic carcass, because architecture, the least understood and the most forgotten of the arts today is perhaps also the most aesthetic, the most mysterious and the most nourished with ideas. It has had the privilege, across the centuries, of symbolizing as it were each age, of summarizing 10 in a very small number of typical monuments a race and a civilisation’s way of thinking, feeling and dreaming. A few temples and churches, palaces and châteaux contain more or less the world’s entire history of art, and express visually, better than books, through the harmony of lines and the charm of ornamentation all the grace and grandeur of an epoch. But I wonder what will be concluded of our generation if some future riot does not topple this tall, skinny pyramid of iron ladders, this ungainly, giant skeleton whose base appears designed to carry a formidable monument of the Cyclops and which aborts in a ridiculous, thin profile of a factory chimney.” Guy de Maupassant, The Wandering Life (1890) So Constantine is identifying himself with a rebellious artist of a generation just before him, an artist who revolts against what is considered by the bourgeoisie to be “high art.” With what rebellious artist of a generation just before him should the Connie of my adaptation identify ?? Allen Ginsberg, of course! The Beatnik poet! His most famous (and infamous) poem Howl, published in 1956, was (and still is) a controversial, revolutionary rant against the traditional poetry and bland American life of his time. Fortuitously, Eric Wunsch, the actor playing Connie in my Seagull, is a Ginsberg fanatic. I will give him the choice of what lines he wishes to quote from Howl. Here’s an excerpt from my adaptation, with two possible Ginsberg lines I’ve suggested (Eric might choose other lines; he’s the Ginsberg expert, not I!): Allen Ginsberg at the Royal Albert Hall 1965 Photographed by John Hopkins “To me, this theatre, this god-awful theatre, is so predictable, so conventional. The curtain goes up, and inside this three-walled box lit up by artificial light, these great geniuses, these priests and priestesses of holy art, they all prance about, pretending to look like people eating, drinking, making love, wearing clothes. And when they try to pass off this trite warmed-over junk as somehow good for us, I just want to run away. Screaming. Like Ginsberg’s hipsters. ‘Angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night!’ [Or: ‘Angelheaded hipsters…who threw potato salad at CCNY lecturers on Dadaism and subsequently presented themselves on the granite steps of the madhouse with shaven heads and harlequin speech of suicide, demanding instantaneous lobotomy!’] PETER: What? CONSTANTINE: Howl! PETER: What??? CONSTANTINE: HOWL! I want to howl at her hack, hack, hack theatre!” If you want to read Howl in its entirety, it’s published online by the Poetry Foundation at http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/179381. Be forewarned. The language is raging and raw. Its publisher, Ginsberg’s friend and fellow poet, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, was arrested by the San Francisco police department, which deemed it to be obscene. The ensuing trial attracted national publicity, and the judge was persuaded to rule it acceptable as poetry. The Poetry Foundation article that accompanies Howl states: “The qualities cited in its defense helped make Howl the manifesto of the Beat literary movement. Including such novelists as Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs and poets Gregory Corso, Michael McClure, Gary Snyder, and Ginsberg, the Beats wrote in the language of the street about previously forbidden and unliterary topics. The ideas and art of the Beats greatly influenced popular culture in America during the 1950s and 1960s.” 11 QUESTIONS Which character are you? Are you looking for love to: Relieve you of your money woes? Escape an unhappy relationship? Fill your life with glamour and fame? Build your self-image and to counter the loneliness of your work/life? To give you inspiration? Questions about Seagull What is Chekhov saying about Love? Fame? Regret? Why do so many of the characters desire those they cannot have? What is the effect of having much of the play’s action take place off stage? Why do you suppose Chekhov ended the play before the audience is able to witness Irina discovering her son’s death? What does the dead seagull symbolize? MY SEAGULL, MY MUSIC by Laurie McCants Because I have set my adaptation of SEAGULL in the 1960s, I can draw upon the music of my youth for the sound score. I’ve always counted myself lucky to have been a teenager at the time when the first records came out of the Beatles, Aretha Franklin, the Rolling Stones, Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, the Supremes, Buffalo Springfield… well, the list could go on and on. They say the music of your youth remains the music you love for the rest of your life. And while I certainly enjoy listening to current artists (St. Vincent, Tuneyards, Andrew Bird, Janelle Monae…), it’s been a particular pleasure returning to the songs that glued me to KAKC-970AM (“The Big 97”) radio station when I was 13 to 16 years old. The final score won’t be selected until sometime in the rehearsal process (which begins about two weeks from when I’m writing this). But I’ve got a working song list; each song I picked because it says something about the story of SEAGULL and because the song has personal resonance for me (ah, yes—this has brought back to me the loves, unrequited and otherwise—of my youth!). Here’s what I’ve picked so far: 12 “I Can’t Get No… Satisfaction”: The Rolling Stones “Yes, I’m Ready”: Barbara Mason “Blowin’ in the Wind”: Bob Dylan “Paint It Black”: The Rolling Stones “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away”: The Beatles (also Joe Cocker) “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye”: Leonard Cohen “What’s New, Pussycat?”: Tom Jones “What the World Needs Now Is Love”: Jackie DeShannon “For Your Love”: The Yardbirds If you were to create a sound score for a story about your teen years, what songs would you pick? 13 Works Cited: Anton Pavlovich Chekhov. (2014). The Biography.com website. Retrieved 11:37, Aug 14, 2014, fromhttp://www.biography.com/people/anton-chekhov-9245947 http://headlong.co.uk/ideas/seagulls-two-premieres/ http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/179381 http://krausenotes.blogspot.com/2012_07_01_archive.html Further Study: 'Man in the Case' review: Getting Chekhov right: World News Network has some interesting video of Chekhov’s short stories: http://article.wn.com/view/2014/01/28/Man_in_the_Case_review_Getting_Chekhov_right/ 14