full paper

advertisement

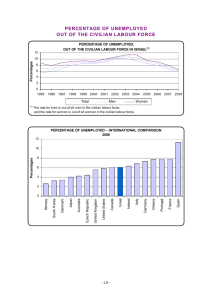

Expectations, job search and the measurement of unemployment in South Africa Dorrit Posel, Daniela Casale and Claire Vermaak posel@ukzn.ac.za; casaled@ukzn.ac.za; vermaakc@ukzn.ac.za University of KwaZulu-Natal August 2012 DRAFT - Please do not quote without the authors' permission Abstract This study interrogates the distinction between searching and non-searching unemployment in South Africa taking advantage of new data available in the national household survey panel, the National Income Dynamics Study. We present three main findings. First, employment expectations are a significant predictor of reported job search among the unemployed: individuals with low expectations of obtaining employment are significantly less likely to be searching for work, providing support for the discouraged worker hypothesis. Second, among the unemployed, search status in the first wave of the panel does not predict labour market status in the second wave, suggesting that the searching and non-searching unemployed do not have different levels of attachment to the labour market. This finding might partly reflect very low persistence in both the searching and non-searching states across the two waves. Third, social networks are the most important means by which the employed find out about their jobs. However, individuals who access social networks passively may not be included in the measure of searching unemployment. We conclude that the distinction between searching and nonsearching unemployment is useful only for highlighting the extent of possible discouragement in the labour force at any one point in time, and not as a means to distinguish 'genuine' work-seekers. Introduction In this study, we interrogate the distinction between searching and the non-searching unemployment in South Africa, and thereby we evaluate the restriction of the official measure of unemployment to the searching unemployed. Who is counted as being unemployed is particularly important in the South African context where the exclusion of the non-searching unemployed results in significantly lower unemployment rates. In 2004, for example, the official rate of unemployment was 26.6 percent, but there were almost as many unemployed not searching for work (4.09 million) as there were searching for work (4.22 million).1 Consequently, a broad rate of unemployment, which includes the non-searchers, would have been far higher at almost 42 percent. We revisit the grounds for excluding the non-searching unemployed from the official measure of unemployment, taking advantage of new data available in the recently released national household survey panel, the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS). Restricting the official rate of unemployment to only the searching unemployed can be justified if searching unemployment and non-searching unemployment are conceptually distinct states, and in particular, if the two groups of unemployed are behaviourally different, with non-searchers being less committed labour force participants. Differences between searching and non-searching unemployment in South Africa have been explored in a number of studies and particularly in work by Kingdon and Knight (2004, 2006, 2007; see also Dinkelman and Pirouz 2002, Ranchhod and Dinkelman 2008, Verick 2012). We augment this research, using more comprehensive data on labour force participation. First, NIDS is the only survey to collect information on employment expectations: all those who were not working but who reported wanting to work were asked whether they thought there was a realistic possibility that they would get a job either in the next month, six months, year or two years. We explore whether there is a relationship between employment expectations and job search, and therefore test whether the non-searching unemployed are "discouraged" rather than uncommitted labour force participants. Second, the release of the second wave of NIDS makes it possible to compare transition probabilities into employment among the searching and the non-searching unemployed. If the likelihood of finding employment differs between the two groups of the unemployed, then this would suggest that non-searching unemployment is distinct from searching unemployment, and there would be good reasons for distinguishing between the two states of unemployment. Third, in contrast to earlier household surveys, NIDS also collects information on how those with wage employment found their job, including active methods of job search (such as "through an employment agency" and "I went to a factory and waited for a job") and passive job search ("a household member told me about the job" or "a friend/relative (in a different household) told me about the job". With these data, we investigate the 1 Own calculations from the September 2004 Labour Force Survey. 1 extent to which the unemployed find employment through passive job methods, and whether successful job-finding strategies differ by the search status of the unemployed. We present three main findings. First, employment expectations are a significant predictor of reported job search among the unemployed. Individuals with low expectations of obtaining employment are significantly less likely to be searching for work, suggesting that individuals are discouraged from job search. Second, among the unemployed, search status in the first wave of the panel does not predict employment status in the second wave. This finding partly reflects considerable fluctuation in search status among the unemployed. Transition matrices reveal very low persistence in both the searching and non-searching states across the two waves. Multinominal logits also show that search status in Wave 1 has no significant impact on labour force status more generally in Wave 2 (i.e. search status is not only unrelated to becoming employed but also to remaining searching unemployed, or to becoming non-searching or not economically active in Wave 2). In addition, we find that social networks are the most important means by which the employed find out about their jobs. However, individuals who access social networks passively may not be included in the measure of searching unemployment. We conclude that the distinction between searching and non-searching unemployment is useful only for highlighting the extent of possible discouragement in the labour force at any one point in time, and not as a means to distinguish 'genuine' work-seekers. In the next section, we review studies which investigate whether the searching and nonsearching unemployed are behaviourally distinct, and particularly in the South African context, and in section 3, we describe the data that are used in this study. Section 4 explores the relationship between employment expectations and searching behaviour, section 5 investigates labour market transitions among the unemployed, and section 6 describes the method by which the employed access information about their current employment. The final section summarises the key findings of the study and considers the implications for the measurement of unemployment in South Africa. 2. Review The appropriate definition of unemployment has long been debated. When measured using micro-data collected in household surveys, the unemployed include individuals who report that they are not working but that they want, and are available, to work. However a key issue is whether this group should then be restricted to those individuals who report also searching for work for some period prior to the survey; and if so, what counts as searching for employment? At the heart of the debate is why people, who say that they want to work, are not also searching for work? In particular, is there a difference between the labour force attachment or work aspirations of the non-searching and searching unemployed? The discouraged worker hypothesis suggests that "people with poor labour market expectations become discouraged in their job search … because the probability of finding 2 a suitable job after a certain period is too low" (van Ham et al 2001:1734). Such individuals are also referred to as the "hidden unemployed" (Mincer 1973; Buss and Redburn 1988), because they would be excluded from official unemployment statistics that require the unemployed to have searched for work. Evidence of a discouraged worker effect was first tested as a response to the business cycle. It was suggested by Long (1958) that labour supply may exhibit cyclical behaviour, increasing during economic upturns and falling during recessions. This hypothesis has often been tested using macro-data, by examining how aggregate trends change with GDP. Studies have produced mixed findings on whether or not labour supply varies with the business cycle (for a review, see Benati 2001). The discouraged worker hypothesis has also been tested using micro-data, particularly in the psychology literature using the expectancy-value theory (for example, Feather and O’Brien 1987; Feather 1992). This theory is a type of cognitive framework of motivated behaviour. In the context of unemployment, the expectancy-value theory hypothesises that an individual’s motivation to search for a job is positively related to expectations about the likelihood of obtaining a job and to the value placed on a job. Thus both the intensity and type of job search behaviour that individuals undertake depend on their assessment of the probability that they will be able to find work (Feather 1992; Vansteenkiste et al 2005). Empirical evidence drawn from micro-data on the discouraged worker effect is also mixed. Some studies find that the probability of employment has a large impact on the intensity of job search (cf. van Ham et al 2001); while others find either that having high expectations of success does not affect the frequency of job search behaviour (Feather and O’Brien, 1987; Oettingen and Mayer, 2002) or that optimism about finding a job is associated with a lower job search intensity, perhaps due to confidence about the ease of finding work (Vansteenkiste et al, 2005). To investigate whether the searching and non-searching unemployed are behaviourally distinct, studies have also compared transition probabilities into employment between these two groups of the unemployed. While most studies find that the non-searching unemployed exhibit different degrees of labour market attachment from the searching unemployed and the economically inactive (Jones and Riddell 1999, 2006; Marzano 2006), others find that the non-searching unemployed are behaviourally similar to those who are out of the labour force (Clark and Summers 1980; Elliott and Dockery 2006). The question of the appropriate measure of unemployment, and the related concern of what counts as search behaviour, is particularly important to interrogate in the South African context. Very high unemployment rates, which have been sustained during periods of economic growth, are far higher still when the non-searchers are counted as unemployed (cf. Casale et al 2004; Kingdon and Knight 2006; Kingdon and Knight 2007; Banerjee et al 2008). This is clearly illustrated in Figure 1, which describes "strict" (searching) unemployment rates and "broad" (including the non-searching) unemployment rates using comparable labour force survey data from 2000 to 2007. 3 Figure 1. Strict and Broad Rates of Unemployment (%) Source: September Labour Force Surveys 2000 – 2007 Notes: Data are weighted. Working age is defined as 15 to 65 years. In addition to the low probability of finding employment, significant resource constraints would also be expected to raise the relative costs of job search. A number of studies have estimated that headcount poverty rates in South Africa exceeded 50 percent during the period 1993 to 2008 (cf. Hoogeveen and Özler, 2005; Ardington et al 2006; Leibbrandt et al 2010; Posel and Rogan 2012). With the economic marginalization of rural areas, particularly in the former Bantustans of apartheid South Africa, many South Africans also only gain access to employment by migrating often considerable distances to nodes of employment, thereby considerably raising the costs of searching for work. Given these circumstances, job-seekers may not actively search for work, but may rely on social networks to provide information about when an employment opportunity becomes available (Kingdon and Knight, 2006; Schoer and Leibbrandt, 2006). From 1998, however, the official statistical agency of South Africa (Statistics South Africa, or Stats SA) adopted the strict or narrow measure of unemployment as the "official" measure for South Africa, requiring the unemployed to have "taken active steps to look for work or to start some form of self-employment" (Stats SA 1998: 1). In explaining the preference for the strict over the broad unemployment rate, Stats SA cites both the desire for international comparability and measurement issues. In Stats SA (1998:63), it is noted that the expanded unemployment rate "introduce(s) more subjectivity into the measure of the unemployment rate, and instability in tracking trends, as it is more difficult to distinguish what constitutes ‘wanting’ a job than to say whether someone has engaged in definite actions to find one". The implication is that by not searching for work, individuals fail to signal that they are committed labour force participants or that they have strong work aspirations. 4 Ironically, despite using a strict definition of unemployment as its official rate, Stats SA often labels the non-searching unemployed as "discouraged workers" in its statistical releases, thereby acknowledging that job search and work aspirations should not be conflated. In addition, it acknowledges the existence in South Africa of various labour market conditions, such as a lack of labour absorption, that make an expanded or "broad" definition, which includes the non-searching unemployed, appropriate (Stats SA 1998: 63). Kingdon and Knight (2004 and 2006) explore the empirical question of why individuals do not search for work in South Africa, using household survey data collected in 1993 by the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU). They find that the unemployed live in households with lower levels of income and expenditure, and lower perceived quality of life, than the employed. This suggests that the unemployed are worse off than the employed, and thus do not voluntarily choose unemployment (Kingdon and Knight 2004). In addition, the non-searching unemployed have satisfaction levels that are no higher than the searching unemployed. They argue that this is consistent with the non-searching unemployed being discouraged from active job search, rather than exhibiting a lack of attachment to the labour market (Kingdon and Knight 2006). However, these studies are based on an early cross-sectional data source with several limitations: the authors could not investigate the relationship between employment expectations and job search, or estimate employment transitions; and they could compare well-being across labour market states only at the level of the household, and not the individual. Other studies use South African panel data to compare transition probabilities into employment between the two groups of the unemployed. Using Labour Force Survey (LFS) panel data for 2001 to 2003, Ranchhod and Dinkelman (2008) find that although the searching unemployed are more likely than the non-searching to gain formal employment, transition rates into employment are low from both unemployment categories. In contrast, there is substantial churning between these two unemployment states, and between unemployment and economic inactivity (Ranchhod and Dinkelman 2008). Using data from the more recent Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) from 2008 to 2010, the non-searching and searching unemployed are shown to be distinct across a range of observable characteristics (Verick 2012). While there is churning between the two unemployment states, the odds of discouragement increased and individuals became less likely to change states during the recent recession. However, both studies are limited by the nature of the panel data used. In particular, the data are derived from a rotating panel of dwelling places, so that individuals who move dwelling places are lost to the panel. If the searching or non-searching unemployed are more likely than the employed to change their place of residence and attrite from the panel, (for example because they gain access to employment by migrating from their household), then the sample is likely to underestimate transitions from searching or non-searching unemployment into employment. 5 3. Data and definitions We use data from the first two waves of the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS), conducted by the Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU) in 2008 and 2010/2011. In contrast to previous national household panels in South Africa, NIDS is designed as a panel household survey that follows the individual. Wave 1 collected information on approximately 28 000 individuals (living in 7 300 households) and Wave 2 successfully re-interviewed just over 22 000 of these individuals (or 78 percent of the original sample). The NIDS data offer a number of advantages over earlier labour market data for South Africa. As outlined in the introduction, we have information on how soon the unemployed expect to find work, allowing us to test directly whether the non-searching unemployed have lower expectations regarding their employment prospects. As NIDS is the first South African survey designed as a nationally representative panel of individuals, we are also able to examine if search behaviour influences whether the unemployed actually found work two years later. Lastly, the questionnaire asks the wage employed to identify how they found their job, providing some insight into the nature and success of job-finding strategies in South Africa. In NIDS the unemployed are identified as those who said they would have liked to work for pay, profit or family gain in the four weeks prior to the survey. Search status is then determined by whether the individual reported having engaged in at least one of a number of activities either to search for work or to start a business over that period. In 2008, 74 percent of the unemployed had engaged in at least one of the activities detailed in Table 1. Enquiring at various workplaces (36.9 percent), seeking assistance from friends and relatives (28.6 percent), and answering advertisements (21.1 percent) were the three most popular job search strategies. However, more than a quarter (or 1.3 million individuals aged 18 to 59 when weighted) reported not undertaking any of the activities identified to search for work. Including these non-searchers in the measure of unemployment would increase the unemployment rate by eight percentage points, from 23 percent to 31 percent. The definition of job search in the NIDS question is relatively broad, and it includes activities that in some countries might be considered passive job search. 2 In the United States, for example, looking at job advertisements is classified as a passive method of job search (Jones and Riddell 1999). Nonetheless, it is possible that certain job-finding methods are not identified in the question. One likely omission concerns the role of social networks. Although social networks are included as a response option, this is phrased in the active voice - individuals have "sought assistance from relative or friends". 2 The question on search activity in NIDS includes the same response options as those in the official labour market surveys conducted by Statistics South since 2008 (the Quarterly Labour Force Surveys). (The 2000 – 2007 biannual Labour Force Surveys did not include ‘Searched through job advertisements on the internet’ and ‘Sought financial assistance to start a business’ although the rest of the wording was the same). 6 Consequently, the more passive act of waiting at home for a friend, relative or previous employer to contact the person about a job might not be captured. Table 1: Job search activity among the unemployed, 2008 Job search activity Registered at an employment agency Enquired at workplaces, farms, factories, or called on other possible employers Placed advertisement(s) Answered advertisements Searched through job advertisement(s) on the internet Sought assistance from relatives or friends Looked for land, building, equipment or applied for permit to start own business Waited at the side of the road Sought financial assistance to start a business Other Nothing N % 14.69 36.85 11.08 21.05 8.31 28.63 5.15 8.77 0.96 1.44 25.93 2667 Source: NIDS 2008 Notes: The data are weighted. The sample consists of the unemployed aged 18 to 59. Percentages do not add up to 100 because multiple response options were allowed. Definitional issues aside (we return to these later in the paper), what else might explain why so many individuals who claim that they want work are not searching for work? There are two possible explanations. The first is that individuals are misreporting their employment intentions: individuals who are not searching for work have a low level of commitment to being employed. Alternatively, the job search literature tests the explanation that individuals cease job search if the costs of searching are too high relative to the likely benefits – that is, they become discouraged. In the next section, we interrogate this further by exploring whether there are key differences between the searching and non-searching unemployed that might point to a discouraged worker effect. 4. Employment expectations and job search To test for discouragement among the non-searching unemployed, we investigate the relationship between employment expectations and job search. In NIDS, all the unemployed are asked whether they think there is a realistic possibility that they will get a job in the next month, six months, year, or two years. Table 2 shows that the distribution of employment expectations amongst the unemployed is bimodal. A third of all of the unemployed do not expect to find a job within the next two years. However, twenty percent of individuals believe that there is a realistic possibility they will get a job within the forthcoming month, with similar proportions expecting to find work within six months or one year. The non-searching unemployed clearly have lower expectations regarding their employment prospects than the searching employed. In comparison to non-searchers, 7 searchers are significantly more likely to expect employment within the next month (23 percent compared to 10 percent), and significantly less likely to expect their unemployment to continue beyond two years (26 percent compared to 48 percent). Table 2. Employment expectations among the unemployed, by search status, 2008 All Searching Non-searching Not within 2 years 0.320 0.264 0.482 Within 2 years 0.084 0.090 0.067 Within 1 year 0.200 0.201 0.196 Within 6 months 0.198 0.212 0.157 Within the next month 0.197 0.232 0.098 N 1983 1312 671 Source: NIDS 2008 Notes: The data are weighted. The sample includes the unemployed aged 18 to 57 years in 2008, who were present in both waves 1 and 2 of NIDS. The proportions in each column may not add to 1 because of rounding. We test whether these differences remain significant when also controlling for other key characteristics of the unemployed. We use a logit model, as the dependent variable is a binary indicating whether or not the individual had searched for work. Our sample consists of all the unemployed aged 18 to 57 years in Wave 1 who had been successfully interviewed in both waves of the panel.3 The results, reported in Table 3, suggest that even when controls are included for a range of individual, spatial and household level variables, expectations remain a strong predictor of search behaviour (Regression II). The unemployed who expected to find work within a month or six months were particularly more likely to be searching than those who did not expect to find work within two years (the omitted category). This positive relationship between expectations and job search clearly would support the argument that non-searching unemployment is associated with discouragement in South Africa. What are the other significant predictors of job search? Of the standard set of basic demographic characteristics we include, only age and education are significant correlates of job search behaviour, with younger adults (26-35 years) and those with a matric or tertiary education more likely to search for work, while race and gender seem to have no independent effects. 3 We chose this upper age range so that we are able to use a balanced sample of working age individuals when we explore employment transitions two years later (by 2010 the pension had been equalized for men and women at 60 years of age). 8 Table 3: Logit regressions on job search status, 2008 Dependent variable = 1 if searching; =0 if non-searching Expect a job within 1 month Expect a job within 6 months Expect a job within 1 year Expect a job within 2 years Female African Indian Coloured Aged 18-25 Aged 26-35 Gr 8- Gr 11 Matric Diploma/degree Urban formal Urban informal Rural formal District unemployment rate Married Work experience Unemployed for 1-4 years Unemployed for 5 years or more Other household member employed Presence of very young children Presence of young children I II II 1.465*** (0.249) 0.901*** (0.193) 0.627*** (0.197) 0.900*** (0.278) 1.246*** (0.253) 0.751*** (0.226) 0.332 (0.210) 0.560* (0.300) -0.243 (0.178) 0.031 (0.957) -1.647 (1.380) -0.318 (0.968) 0.275 (0.243) 0.414** (0.203) 0.159 (0.189) 0.795*** (0.246) 0.889** (0.371) 0.353* (0.199) 0.706** (0.290) 0.486 (0.325) 0.099 (0.660) 0.056 (0.210) 0.273 (0.181) 0.245 (0.222) 0.358 (0.246) 0.229 (0.165) -0.347** (0.155) 0.025 (0.149) -0.292* (0.176) -0.163 (0.953) -1.381 (1.305) -0.431 (0.963) 0.316 (0.236) 0.426** (0.200) 0.204 (0.188) 0.863*** (0.241) 1.032*** (0.375) 0.369* (0.197) 0.728*** (0.280) 0.431 (0.311) -0.035 (0.651) 0.061 (0.214) 0.260 (0.178) 0.118 (0.210) 0.146 (0.237) 0.275* (0.162) -0.346** (0.154) -0.010 (0.146) 9 Presence of older children Difficulty in daily activities Province controls Constant N No 0.450*** (0.106) 1983 -0.056 (0.156) -0.400** (0.204) Yes -0.871 (1.129) 1908 -0.008 (0.154) -0.375* (0.203) Yes -0.106 (1.117) 1908 Source: NIDS 2008 Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.10 Regressions are weighted. The sample consists of all those, aged 18 to 57 in wave 1 who reported not working but wanting to work. In addition to the unemployed with low employment expectations, those who live with very young children (aged 3 or younger) and who are in poor health (i.e. who have difficulty performing certain daily activities) are less likely to engage in job search. These findings are also consistent with a discouraged worker effect. The constraints posed by childcare responsibilities and ill health would raise the costs of job search relative to the benefits. In a similar vein, the results on area type may also reflect the higher costs of searching for those who live further away from areas of employment. The unemployed living in urban areas, and particularly in urban informal settlements (which often develop close to places of employment, Hunter and Posel 2012), are much more likely to search for work compared to those living in rural areas. In the final column of Table 3 we exclude the expectations variables from the regression, as a number of our controls are likely to be correlated with individuals’ expectations about employment prospects. The results in Regression III give us some insight into how expectations are formed. The coefficients on the education variables increase somewhat when expectations are excluded, indicating as we might predict that those who are more educated expect to find work sooner. The female dummy and the variable capturing whether there are other employed household members now become marginally significant in predicting job search. The results suggest that among the unemployed, women and those who live in households where no-one is employed, are less likely to expect to find work, and therefore less likely to search for work. We were surprised that neither the local unemployment rate nor the unemployment duration variables were significant correlates of job search. A high local unemployment rate and longer spells of unemployment may be expected to discourage job search. The local unemployment rate was estimated at the level of the district council because the sample sizes in NIDS (and other national household surveys in South Africa) are too small to be representative at the municipality or cluster levels. However, the district might not be the relevant unit of analysis if individuals look to the experiences of those who are more geographically proximate. In the case of the unemployment duration variables, we were concerned that they might be too closely correlated with whether the individual had worked before. When we excluded the work experience variable from the regressions, however, there was no substantive difference to the results. When we excluded the unemployment duration variables, work experience became significant at 10 the 10 percent level, but the effect disappeared once expectations were controlled for (suggesting that those who had worked before expected to find work sooner). 5. Employment transitions among the unemployed Data collected in NIDS show that among the unemployed, individuals who have low expectations of finding work, and those who face job search constraints, are significantly less likely to search for work. These findings are consistent with the discouraged worker hypothesis and they challenge the assumption that by not searching for employment, the unemployed signal low work aspirations. In this section, we explore further whether the labour market attachment of the unemployed differs, depending on their search status. In particular, we exploit the panel nature of the data to test whether the searching unemployed are more likely than the non-searching unemployed to transition into employment, while the non-searching unemployed are more likely to exit the labour force. We identify four labour market states: not economically active; unemployed but not searching for work; searching unemployed; and employed. At a descriptive level, the transition matrix in Table 4 does not suggest very large differences in the likelihood of entering any one of these states between the searching and the non-searching unemployed (none of the differences is significant). It is also interesting that the greatest levels of persistence in labour market status are for the employed and the not economically active (where the majority remained in the same category, 71 and 59 percent respectively), while there is a substantial amount of churning among the unemployed. Only 10 percent of the non-searching unemployed and 22 percent of the searching unemployed in Wave 1 were in those same categories in Wave 2.4 Table 4. Transition matrix of employment status between W1 and W2 (percentages) Wave 2 employment status NEA NonSearching Employed Total Wave 1 searching employment status NEA 5.58 14.95 20.07 100 59.4 Non-searching 44.04 18.59 27.28 100 10.09 Searching 39.37 6.36 32.76 100 21.51 Employed 18.92 3.32 7.063 100 70.69 Total 34.82 4.87 12.41 47.9 100 Source: NIDS 2008 and 2010/11 Notes: Data are weighted. Sample includes those aged 18 to 57 in Wave 1 who were successfully reinterviewed in Wave 2. 4 As we are analysing changes between Waves 1 and 2 in this section, we make use of the panel weights provided with the dataset, which are designed to correct for attrition bias 11 There is also considerable movement between the two states of unemployment. Among the non-searching in Wave 1, 19 percent reported searching for employment in Wave 2. The non-searching unemployed are therefore almost as likely to transition into searching unemployment as the searching are to remain searching.5 This fluidity in job search behaviour is consistent with what Verick (2012: 402) finds in his transition analysis using the rotating panel from the Quarterly Labour Force Surveys from 2008 and 2009: “Of particular interest is the high rate of transitions from discouragement into narrowly defined unemployment (and vice versa), which reflects the decision to undertake job search changes over time, even from one quarter to the next” (see also Ranchhod and Dinkelman 2008). We explore these transitions further in the multivariate context, using a multinomial logit model in which the categories of the dependent variable correspond to the four Wave 2 labour market states outlined above. The reference category in the regression consists of the not economically active in Wave 2. We use the same sample as in the job search regressions, i.e. the unemployed aged 18 to 57 years in Wave 1 (20 to 59 years in wave 2) who appear in both waves. Our key variable of interest is the Wave 1 search status of the unemployed, as we are interested in whether the searching unemployed have a different attachment to the labour market compared to the non-searching unemployed. We include controls for gender and race, which are unchanged between the waves. For the other explanatory variables, we use their Wave 1 values to help address possible endogeneity in these variables. In Table 5, we report the results for the "full" specification, which models all the controls, including the individual's expectations about finding employment. However, because of concerns with collinearity, particularly between search status, expectations and the other explanatory variables, we also report the results for two other specifications in the Appendix - one which includes a far more reduced set of controls consisting of basic demographic characteristics (Table A1), and one which includes all the variables except for those on employment expectations (Table A2). In none of the specifications is search status in the first wave a significant predictor of finding employment in the second wave: among those who were unemployed in Wave 1, the searching are no more likely than the non-searching to be employed in Wave 2. In fact, Wave 1 search status is not a significant predictor of being in any of the three labour market states in Wave 2, compared to being out of the labour force. The key determinants of transitioning into employment reflect the individual's human capital: the likelihood of employment increases non-linearly in age and among those with tertiary education and work experience6. Women and those who were living with young children (aged 4 to 8 5 The biggest movement for both groups of unemployed was out of the labour force (44 percent for the nonsearching and 39 percent for the searching). This may signal that over this period of economic downturn, those who are particularly discouraged withdraw from the labour force altogether. 6 Some of those who were unemployed in both Waves 1 and 2 might have worked in the intervening period. The data from Wave 2 suggest the numbers are likely to be negligible, however. Over 90 percent of the unemployed in both waves said they had never worked before in response to this question in Wave 2, and of those who had, the majority (64%) reported that more than a year had lapsed since they last worked. 12 years) were less likely to be working in Wave 2. These findings remain robust across the different specifications for the multinominal logit. Table 5. Multinomial logit of Wave 2 labour market status among the Wave 1 unemployed Wave 2 status Reference category: NEA Non-searching Searching Employed Searching unemployed in Wave 1 -0.354 0.094 0.080 (0.267) (0.209) (0.192) Expect a job in 1 month 1.208*** 0.157 0.116 (0.406) (0.295) (0.267) Expect a job in 2 months 0.334 0.166 0.184 (0.388) (0.254) (0.234) Expect a job in 1 year 0.784* -0.113 0.112 (0.402) (0.270) (0.240) Expect a job in 2 years 1.079** -0.137 0.322 (0.455) (0.329) (0.300) Female 0.454 -0.105 -0.606*** (0.338) (0.213) (0.189) African 1.194 1.745 0.500 (1.298) (1.213) (0.787) Indian 2.486 1.271 1.566 (1.596) (1.533) (1.171) Coloured 1.455 2.204 0.642 (1.424) (1.421) (0.866) Married 0.350 -0.642*** -0.270 (0.370) (0.242) (0.236) Age 0.051 0.132* 0.150** (0.099) (0.068) (0.066) Age2 -0.139 -0.234** -0.233** (0.137) (0.096) (0.093) Grade 8 to grade 11 -0.508 -0.139 0.000 (0.373) (0.251) (0.224) Matric -0.738 -0.119 0.124 (0.460) (0.291) (0.261) Diploma/degree 0.152 0.470 1.092*** (0.499) (0.415) (0.341) Urban formal 0.077 0.100 0.115 (0.321) (0.256) (0.222) Urban informal 0.691 0.365 0.470 (0.470) (0.342) (0.292) Rural formal -1.433** -0.382 0.101 (0.692) (0.376) (0.305) District unemployment rate -2.232* 1.133 -0.414 (1.350) (0.811) (0.771) Work experience 0.058 0.203 0.426** (0.300) (0.215) (0.190) Unemployed 1-4 years 0.034 0.135 -0.002 (Unfortunately the response categories do not correspond to the lag between the waves, but the numbers are so small in any case). 13 Unemployed 5 years or more Other household member employed Presence of very young children Presence of young children Presence of older children Difficulty in daily activities Constant N (0.381) 0.461 (0.457) -0.430* (0.261) -0.033 (0.293) -0.301 (0.265) -0.368 (0.254) -0.560 (0.365) -3.370 (2.248) 1896 (0.260) 0.204 (0.288) -0.315* (0.188) -0.143 (0.189) 0.124 (0.185) 0.011 (0.194) 0.113 (0.264) -5.421*** (2.045) (0.213) -0.333 (0.249) -0.194 (0.176) 0.019 (0.170) -0.311* (0.171) 0.021 (0.173) -0.172 (0.243) -2.645* (1.375) Source: NIDS 2008 and 2010/2011. Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.10. Sample consists of the unemployed aged 18 to 57 in Wave 1. Province controls included. In the full specification, employment expectations also do not predict employment status. Among the unemployed in Wave 1, those who reported positive employment expectations were no more likely than others to be employed, rather than not economically active, in Wave 2.7 However, they were significantly more likely not to be searching for work than not economically active. This would suggest that when the employment expectations of the unemployed are not realised, they are more likely to stop searching for work than to exit the labour force altogether. Of the remaining variables, few are useful in distinguishing between transitions into searching versus non-searching unemployment, rather than out of the labour force. Employment transitions among the unemployed therefore do not differ by the search status of the unemployed. This finding is not consistent with the argument that searching and non-searching unemployment are distinct states and that by not searching for work, the unemployed signal a lower level of commitment to the labour force. Rather, the large degree of fluidity in whether or not the unemployed report searching for work, identified in the transition matrix above, may be one explanation for why search status does not predict employment status. In the next section, we explore another possible explanation, by investigating the job-finding strategies of the employed. 6. Job-finding strategies of the employed Low levels of persistence in either the searching or non-searching unemployment states provide one reason for why the likelihood of finding employment in Wave 2 does not differ by the search status of the unemployed in Wave 1. A further explanation, which we 7 This finding is robust also when expectations are modelled using a reduced set of controls. 14 explore in this section, is that individuals find employment through passive search methods, which are not recorded as search activity in the survey. In NIDS, all those individuals who reported having wage employment are asked how they found out about their job. The response options, detailed in Table 5, largely mirror those provided to identify the job search activity of the unemployed. However, an important difference concerns how social networks are identified. Whereas the job search question requires individuals actively to have sought assistance from friends or relatives, the response options for the job-finding question are framed in the passive voice: "A household member told me about the job" or "A friend/relative … told me about the job". Table 5. Job finding strategy of the wage-employed (Wave 2) Advert in newspaper/internet Advert on notice board e.g. in shopping centre Household member told me about the job A friend/relative (in a different household) told me Went to a factory and waited for a job Knocked on factory gates, visited shops and homes Through an employment agency Asked someone who had employed me before Waited on the side of the road Other N All (regardless of labour force status in Wave 1) 18.43 (1.15) 5.00 (0.59) 3.81 (0.43) 43.51 (1.46) 7.52 (0.75) 6.00 (0.64) 6.60 (0.88) 6.28 (0.66) 2.36 (0.40) 0.49 (0.19) 2618 Searching unemployed in Wave 1 Nonsearching unemployed in Wave 1 7.02 (1.57) 4.10 (1.48) 3.45 (1.13) 51.50 (4.49) 11.73 (3.45) 6.25 (1.67) 5.17 (2.51) 5.63 (1.60) 3.39 (1.84) 1.75 (1.14) 257 6.31 (3.38) 12.33 (5.16) 5.69 (2.13) 54.50 (7.71) 8.11 (5.45) 2.76 (1.55) 2.78 (2.21) 6.66 (3.47) 0.86 (0.62) 0.00 (0.00) 100 Notes: The data are weighted. Standard errors are in parentheses. The full sample includes those aged 18 in 2008 to 59 years in 2010, who had wage employment in Wave 2 of NIDS; and the two sub-samples are restricted to those who also reported being unemployed in Wave 1. Table 5 compares the job-finding strategies of the wage employed in Wave 2 of the panel. We consider three samples. The first sample, in column one, represents all those (aged 18 to 59 in Wave 2) who had wage employment in Wave 2. The second and third samples are restricted to those who had wage employment in Wave 2 but who were unemployed (either searching or non-searching) in Wave 1. 15 Among all those with wage employment in Wave 2, the modal job-finding strategy, accounting for 44 percent of responses, is a "friend or relative (in a different household) told me about the job". A further four percent of the employed reported that they found out about their employment from a member of their own household. Social networks therefore are the single most important job-finding method of the employed. However, this method may include the more passive 'waiting' to be told about a job, and therefore may not be reflected in the job search responses of the unemployed. Among the employed who had been unemployed in Wave 1 of the panel, social networks accounted for over half of all job-finding responses. The percentage was even higher among those identified as non-searching in Wave 1, with more than 60 percent reporting that they found out about their jobs from friends, relatives or household members (compared to 55 percent of the searching unemployed). This difference would be consistent with a greater reliance on passive job search among the non-searching unemployed, although given small sample sizes, the differences between the two samples of the unemployed are not statistically significant (and not for any of other the jobfinding methods). 7. Conclusion In this paper we revisit the debate around whether the non-searching unemployed should be included in the official rate of unemployment in South Africa. We do this using new data on expectations, employment transitions and job search strategies from a recently released national panel survey. Our findings suggest that the non-searching unemployed form a legitimate part of the labour force, and therefore should be included in both academic and policy discussions about the extent and causes of South Africa’s persistent unemployment problem, as well as the potential responses. First, the positive relationship between expectations about employment prospects and job search behaviour clearly suggests that the non-searching unemployed are indeed "discouraged", rather than misreporting their desire for work. Our findings also point to key constraints in the job search market that would serve to raise the costs of search relative to the expected benefits, including poor health, childcare responsibilities and distance from places of employment. Second, we find that the non-searching unemployed are no less likely to transition into employment, or more likely to transition out of the labour force, than the searching unemployed. This implies search status is not capturing that the searching unemployed are more committed, or successful, labour market participants. In fact there is very little to distinguish whether the unemployed transition into searching versus non-searching unemployment in Wave 2. This may be partly due to the large degree of movement that we identify between the searching and non-searching states over time. But it may also be related to our third finding that the definition of what counts as search is likely to have overlooked a substantial number of the unemployed who engage in passive job search 16 activities. In particular, many of the unemployed choose to wait for relatives, friends or employers to contact them about work, a legitimate search strategy in the context of persistent long-term unemployment and high job search costs in South Africa. If these individuals are classified as non-searching because of how search activity is defined, then the distinction between the searching and non-searching unemployed becomes even less meaningful. 17 Appendix Table A1. Multinomial logit of Wave 2 labour market status among the Wave 1 unemployed: Reduced specification Wave 2 status Reference category: NEA Non-searching Searching Employed Searching unemployed in Wave 1 -0.184 0.154 0.158 (0.257) (0.210) (0.183) Female 0.366 -0.207 -0.680*** (0.306) (0.205) (0.180) African 0.690 2.050* 0.614 (1.194) (1.206) (0.833) Indian 3.046* 1.126 1.519 (1.645) (1.531) (1.141) Coloured 0.968 2.362* 0.771 (1.334) (1.393) (0.911) Age 0.072 0.137* 0.124** (0.080) (0.070) (0.062) Age2 -0.153 -0.240** -0.203** (0.114) (0.102) (0.090) Grade 8 - grade 11 -0.411 -0.077 0.081 (0.373) (0.253) (0.219) Matric -0.495 -0.163 0.211 (0.463) (0.296) (0.258) Diploma/degree 0.188 0.347 1.152*** (0.499) (0.414) (0.329) Urban formal 0.147 0.158 0.207 (0.305) (0.246) (0.218) Urban informal 0.813* 0.373 0.531* (0.433) (0.335) (0.282) Rural formal -1.664** -0.151 0.240 (0.777) (0.374) (0.299) District unemployment rate -1.908 1.249 -0.441 (1.176) (0.774) (0.742) Source: NIDS 2008 and 2010/2011. Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.10. Sample consists of the unemployed aged 18 to 57 in Wave 1. Province controls included. 18 Table A2. Multinomial logit of Wave 2 labour market status among the Wave 1 unemployed: Excluding expectations Wave 2 status Reference category: NEA Non-searching Searching Employed Searching unemployed in Wave 1 -0.212 0.121 0.101 (0.255) (0.207) (0.188) Female 0.366 -0.110 -0.606*** (0.344) (0.214) (0.190) African 0.925 1.712 0.496 (1.216) (1.215) (0.791) Indian 2.842* 1.270 1.616 (1.560) (1.529) (1.185) Coloured 1.328 2.185 0.641 (1.340) (1.423) (0.873) Married 0.350 -0.650*** -0.264 (0.370) (0.242) (0.237) Age 0.071 0.132* 0.149** (0.097) (0.068) (0.066) Age2 -0.167 -0.236** -0.232** (0.135) (0.097) (0.093) Grade 8 to grade 11 -0.404 -0.154 0.014 (0.374) (0.251) (0.222) Matric -0.571 -0.135 0.134 (0.449) (0.294) (0.261) Diploma/degree 0.308 0.474 1.110*** (0.512) (0.416) (0.340) Urban formal 0.083 0.108 0.108 (0.310) (0.257) (0.221) Urban informal 0.743 0.359 0.473 (0.469) (0.342) (0.293) Rural formal -1.523** -0.379 0.108 (0.708) (0.377) (0.301) District unemployment rate -2.250* 1.054 -0.411 (1.334) (0.800) (0.771) Work experience 0.005 0.229 0.414** (0.312) (0.214) (0.187) Unemployed 1-4 years 0.047 0.113 -0.019 (0.375) (0.259) (0.213) Unemployed 5 years or more 0.375 0.159 -0.359 (0.449) (0.290) (0.248) Other household member employed -0.390 -0.312* -0.190 (0.268) (0.188) (0.176) Presence of very young children -0.040 -0.144 0.021 (0.282) (0.188) (0.170) Presence of young children -0.379 0.122 -0.319* (0.267) (0.183) (0.169) Presence of older children -0.303 0.022 0.018 (0.253) (0.191) (0.174) Difficulty in daily activities -0.513 0.107 -0.156 (0.383) (0.262) (0.243) Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. *** p<0.01 ** p<0.05 * p<0.10. Province controls included. 19 References Ardington, C., Lam, D., Leibbrandt, M. & Welch, M. (2006) “The sensitivity to key data imputations of recent estimates of income poverty and inequality in South Africa.” Economic Modelling 23: 822-835. Banerjee, A., Galiani, S, Levinsohn, J, McLaren, J. and Woolard, I. (2008) “Why has unemployment risen in the new South Africa?” Economics of Transition 16(4): 714 – 740. Benati, L. (2001) “Some empirical evidence on the ‘discouraged worker’ effect.” Economics Letters 70: 387 – 395. Buss, T.F. and Redburn, F.S. (1988). Hidden unemployment: Discouraged jobseekers and public policy. New York: Praeger. Casale, D., Muller, C. and D. Posel (2004) “‘Two million net new jobs’: A reconsideration of the rise in employment in South Africa, 1995 – 2003.” South African Journal of Economics 72 (5): 978 - 1002. Clark, K.B. and Summers, L.H. (1980) "Labour force participation: timing and persistence", in R. Cross (ed.) Unemployment Hysteresis and the Natural Rate Hypothesis. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Dinkelman, T. and Pirouz, F. (2002) “Individual, household and regional determinants of labour force attachment in South Africa: Evidence from the 1997 October Household Survey.” South African Journal of Economics 70(5): 865 – 891. Elliott, L. and Dockery, A.M. (2006) “Are the ‘hidden unemployed’ unemployed?” Centre for Labour Market Research Discussion Paper 06/2. Feather, N.T. and O’Brien, G.E. (1987) “Looking for employment: An expectancyvalence analysis of job-seeking behaviour among young people.” British Journal of Psychology 78: 251 – 272. Feather, N.T. (1992) “Expectancy-value theory and unemployment effects.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 63: 315 – 330. Hoogeveen, J. and Özler, B. (2006) “Poverty and inequality in post-apartheid South Africa: 1995-2000.” In: Bhorat, H. & Kanbur, R. (eds.) Poverty and Policy in PostApartheid South Africa. Cape Town HSRC Press. Hunter, M. and Posel, D. (2012) “Here to work: the socioeconomic characteristics of informal dwellers in post-apartheid South Africa.” Environment and Urbanization 24(1): 285-304. 20 Jones, S.R.G. and Riddell, W.C. (1999) “The measurement of unemployment: An empirical approach.” Econometrica 67(1): 147 – 162. Jones, S.R.G. and Riddell, W.C. (2006) “Unemployment and nonemployment: Heterogeneities in labor market states.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 88(2): 314 – 323. Kingdon, G. and Knight, J. (2004) “Unemployment in South Africa: The nature of the beast.” World Development 32(3): 391 – 408. Kingdon, G. and Knight, J. (2006) “The measurement of unemployment when unemployment is high.” Labour Economics 13: 291 – 315. Kingdon, G. and Knight, J. (2007) “Unemployment in South Africa, 1995 – 2003: Causes, problems and policies.” Journal of African Economies 16(5): 813 – 848. Leibbrandt, M., Woolard, I., Finn, A.& Argent, J. (2010) Trends in South African income distribution and poverty since the fall of apartheid. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No. 101. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Marzano, E. (2006)“How many labour force states? An analysis based on the British Household Panel Survey (BHPS).” Labour 20(2): 237 – 254. Mincer, J. (1973) “Determining who are the ‘hidden unemployed’.” Monthly Labor Review March 1973: 27 – 30. Oettingen, G. and Mayer, D. (2002) “The motivating function of thinking about the future: expectations versus fantasies.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83(5): 1198-1212. Posel, D. and Rogan, M. (2012) “Gendered trends in poverty in the post-apartheid period, 1995 – 2006.” Development Southern Africa 29(1): 97-113 Ranchhod, V. and Dinkelman, T. (2008) “Labour market transitions in South Africa: What can we learn from matched Labour Force Survey data?” Southern Africa Labour and Development Research Unit (SALDRU), Working Paper 14, Cape Town: SALDRU. Schoer, V. and Leibbrandt, M. (2006) “Determinants of job search strategies: Evidence from the Khayelitsha/Mitchell's Plain survey.”" South African Journal of Economics 74(4): 702-724. Stats SA (1998) Unemployment and employment in South Africa. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 21 Van Ham, M., Mulder, C.H. and Hooimeijer, P. (2001) “Local underemployment and the discouraged worker effect.” Urban Studies 38(10): 1733 – 1751. Vanseteenkiste, M., Lens, W. and De Witte, H. (2005) “Understanding unemployed people’s job search behaviour, unemployment experience and well-being: A comparison to expectancy-value theory and self-determination theory.” British Journal of Social Psychology 44: 269 – 287. Verick, S. (2012) “Giving up job search during a recession: The impact of the global financial crisis on the South African labour market.” Journal of African Economies 21(3): 373 – 408. 22